This master's thesis investigates efficiency optimization techniques for real-time GPU raytracing used in modeling car-to-car communication systems. Specifically, it aims to improve the simulation of the propagation channel through ray reordering and caching. The research analyzes existing caching schemes exploiting frame coherence, GPU data structures, and ray reordering techniques. It proposes algorithms for ray sorting on the CPU and caching tracing data. The thesis then implements and evaluates the proposed methods, analyzing system performance for static and dynamic scenes. Testing shows ray reordering significantly increases efficiency, though caching provides varying benefits depending on the scheme used.

![1. Introduction

Software efficiency often refers to algorithmic efficiency which is one of the central topics

in computer science. According to Oxford Dictionary of Computing, algorithm efficiency

is “a measure of the average execution time necessary for an algorithm to complete work

on a set of data. Algorithm efficiency is characterized by its order.” [22]. On the other

hand, according to Robert Sedgewick [49], program optimization is a process of modifying

a software system to make some aspect of it work more efficiently or use fewer resources.

The latter implies that there is a software system that behaviour needs to be optimizied.

However, many experts in computer science (e.g Donald Knuth [25]) believe that the crit-

ical code sections have to be throughly verified and found before the optimization takes

place. In our case, efficiency optimization means that it is rather adding a new functional-

ity helping to increase performance then optimization of the existing code. With the term

optimization closely connected terms caching and performance analysis.

1.1. Thesis Statement

The aim of the project is modification of existing software system developed for modeling

of Car-to-Car Communication to increase its efficiency (decrease average time taken for

data processing). The system uses realtime GPU raytracing for simulation of wireless com-

munication between cars. A hypothesis of the research is that the tracing process could be

speeded up by taking into account an innerframe and outerframe coherence i.e. caching of

resulting data for future requests. It is also supposed that the efficiency optimization could

be achieved by altering tracing parameters, for example, by changing an order of rays shot

on a scene. Both hypothesis are tested using performance analysis (benchmarking).

1.2. Motivation

In the Motivation section, it is given a description of a general direction in which the cur-

rent work is carried out. In the first subsection it is briefly described Car-to-Car system,

its general purpose. In the second subsection, it is given some general information about

virtual testing of such systems. The last subsection considers an impact of realtime gpu

raytracing on the virtual drive system and on other urgent scientific areas.

1.2.1. Car-to-Car Communication System

Car-to-Car Communication system is a wireless network “between vehicles and their en-

vironment in order to make the vehicles of different manufactures interoperable and also

enable them to communicate with road-side units.[8]”. According to the Car2Car Com-

munication Consortium, the system shall provide the following top level features:

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-19-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction

• automatic fast data transmission between vehicles and between vehicles and road

side units

• transmission of traffic information, hazard warnings and entertainment data

• support of ad hoc Car 2 Car Communications without need of a pre-installed net-

work infrastructure

• the Car 2 Car system is based on short range Wireless LAN technology

The Car 2 Car Communication System has the following goals:

• enable the cooperation between vehicles

• increase driver awareness

• extend driver’s horizon

• enable entirely new safety functions

• reduce accidents and their severity

• include active traffic management applications

• help to improve traffic flow

Thus, the main scenarios for which the system is designed include safety, traffic efficiency,

infotainment and some others.

1.2.2. VANET Simulation

In general, Car-2-Car communication systems represent a type of Vehicular ad-hoc Net-

works (VANET). Specifics of using a wireless connection in such networks requires an

active development of new network protocols suitable for the task. However, high costs of

full-scale real tests make them disadvantageous. An important part in simulation of such

systems is realistic motion model [12]. Another important issue in VANET simulation is

realistic modelling of propagation channel [26]. For the later problem there are two possi-

ble solutions: statistical and deterministic channel models. The deterministic method uses

a ray-tracing to model wave propagation [10]. The deterministic approach provides a real-

istic simulation taking into account geometrical and radio properties of the environment.

1.2.3. Simulation of Propagation Channel

In modelling of the propagation channel using the ray tracing, there are different ap-

proaches. Some authors, for example, create a radio map using a pre-calculation [15].

Others use a mixed (statistical and deterministic) approach for the channel simulation [6].

All authors, however, agree on that statistical models are unable to provide a necessary

precision in the network simulation. On the other hand, the ray tracing which provides

the seek accuracy suffers from low performance. Thus, the problem of increasing efficiency

of the realtime ray tracing becomes an important step towards building accurate VANET

simulators. The problem is also important in other areas of computer science, for example,

in computer graphics [16].

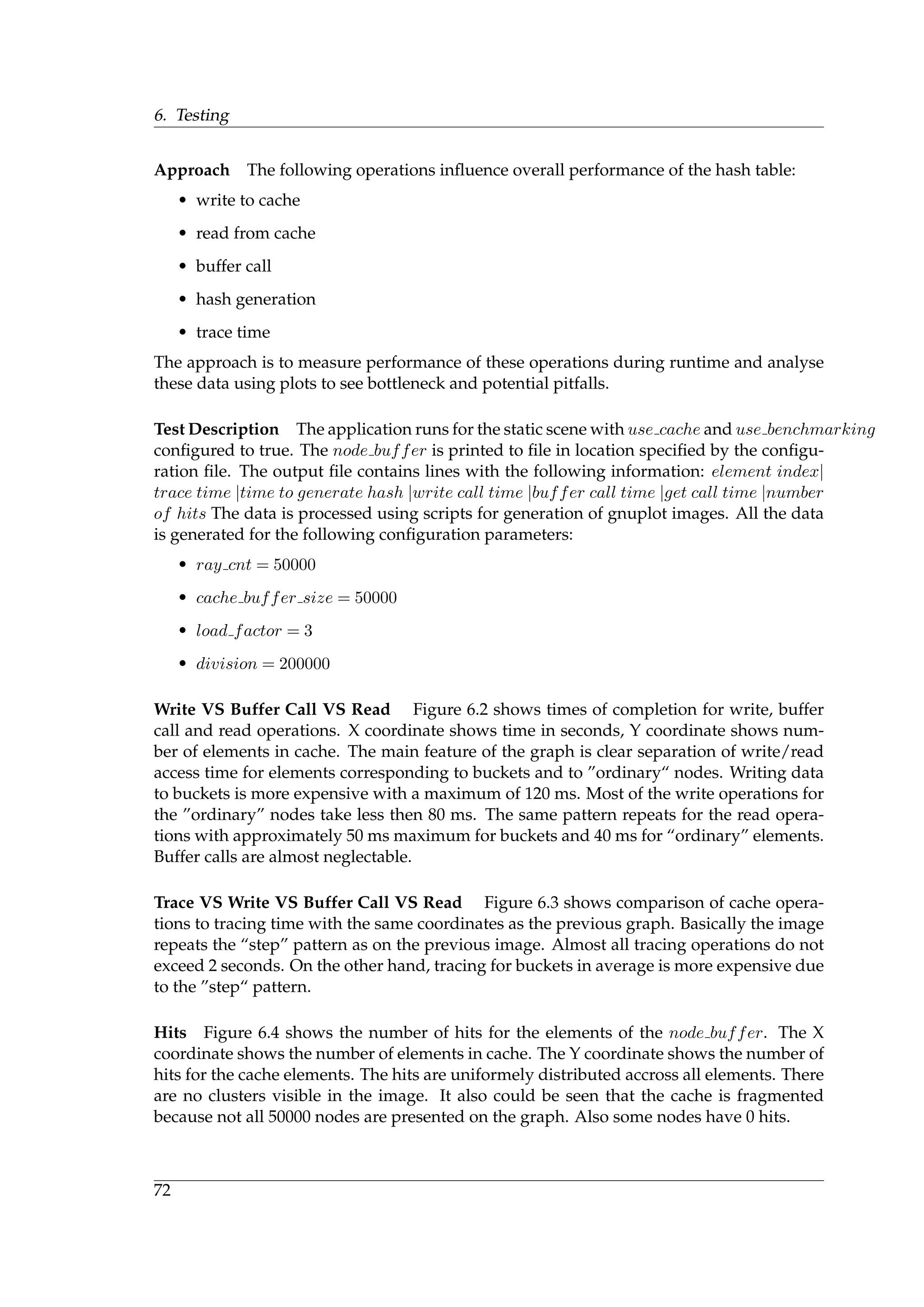

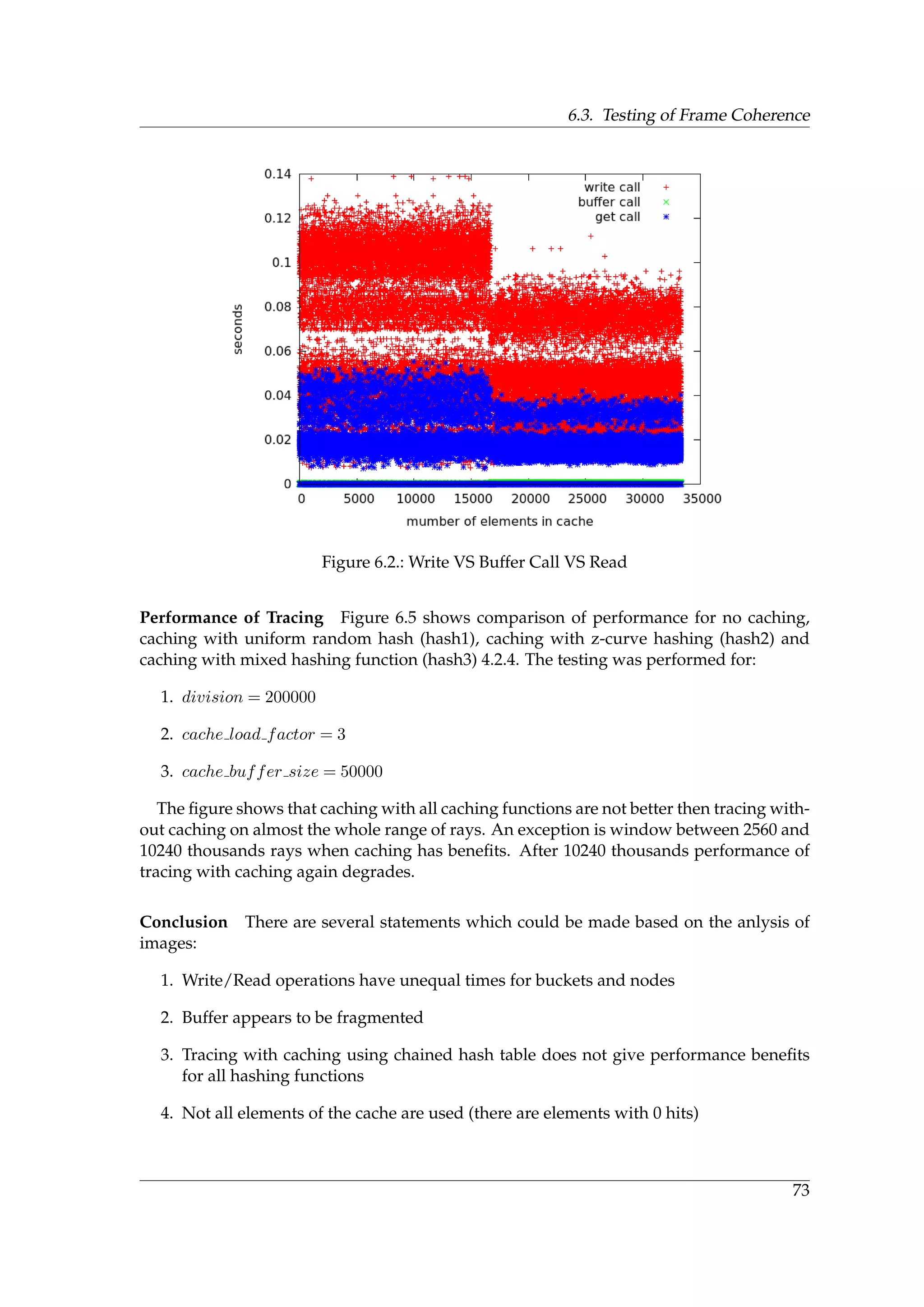

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-20-2048.jpg)

![1.3. Thesis Goals

1.3. Thesis Goals

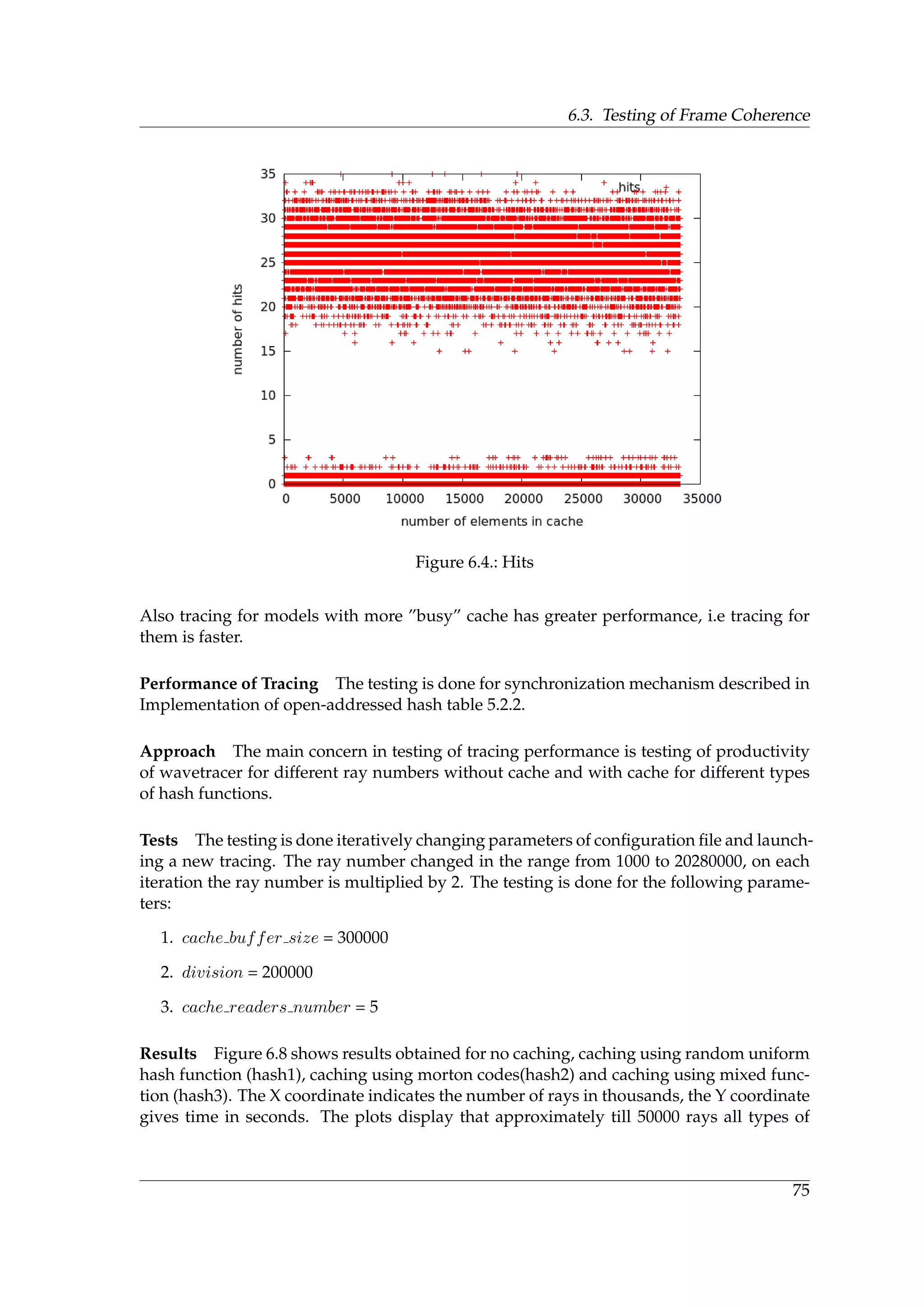

The main goal of the thesis is to increase the efficiency of realtime GPU raytracing in a sys-

tem used for VANET simulation. The main functionality of the system has been developed

by the start of this work. So design goals can be formulated as follows:

1. Increase the system efficiency using the ray sorting

Design of sorting methods (algorithms)

Implementation of sorting methods (CPU)

Testing of the system performance with the ray reordering

2. Increase the system efficiency using caching

Design of caching method

Implementation of caching (GPU)

Testing of the system performance using caching

1.3.1. Ray Reordering

GPU performs calculations separating the streams on groups which are called ”warps“.

The main problem with warp is ”divergence” [4]. Such problem occurs, for example, in

code containing branches when some streams inside a ”warp“ take one branch of the ex-

ecution flow, other suspend on the evaluation point. When the first finish their execu-

tion, others take another branch, so the first group of threads now suspend till the second

group finish their execution. Presorting of rays helps to fully utilize the hardware such

that threads in one warp take the same execution paths.

1.3.2. Ray Cache

On the other hand, caching helps to reduce intensity of computational load. Cache stores

calculations which have been already computed in the system for future requests. The

main problem here is development of the caching schema and also implementation of the

caching on the GPU. The other important thing is testing and evaluation of testing results.

Tests development should be performed using automation tools as much as possible.

1.4. Contributions

The main contibution of this work is development of caching method for a system simulat-

ing VANET with low and medium intraframe coherence. This means that the geometrical

configuration of rays completely changes from frame to frame preserving a certain degree

of correlation. Other techniques use high ray coherence between frames, it means that par-

tially beam configuration stays stable between frames, this allows to reuse tracing results

between frames. In this case, radiation sources change their positions with relatively high

speed between frames.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-21-2048.jpg)

![1. Introduction

The main problem solved in the implementation part is selection of efficient data struc-

ture allowing to build cache on the GPU side. Next, during testing of the data structure

for dynamic scenes, there have been an error that could be contributed to OptiX bugs.

The error has been solved by design of synchronization schema for writing/reading data

to/from buffer. The error in more detail will be described in the Testing chapter.

1.5. Software System Overview

In this section, it is given a brief system overview. Roughly the system contains the fol-

lowing modules:

Wavetracer This module is responsible for the ray tracing using OptiX engine: reading

of configuration file, creation of context, initialization of parameters, tracing programs,

launching of the tracing, processing of the output data, writing of the processed data to

the output file. This is the main module which will be amended.

Sceneviewer This module diplays results of the ray tracing both statically and dynami-

cally using OpenSceneGraph [41].

Osgloader Extracts information out of loaded 3D models.

Optix wrapper The module is a wrapper of OptiX api. C++ API of OptiX does not meet

needs of the application, for example, iterating the scene graph.

edgedetector Detection of diffraction edges.

adtf coupling The software component is responsible for encapsulation of modules into

ADTF [1]. These plugins are osgplugin, testdriverplugin, vtdplugin and wavetracer plu-

gin. All the plugins should inherit basic interfaces of the ADTF.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-22-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

The study was conducted in the following directions: ray caching techniques & frame

coherence, GPU data structures and ray reordering. Also it has been written a review

on GPU programming model and memory types. Ray caching and frame coherence is

presented in one subsection while GPU data structures and ray reodering in separate.

2.1. Ray caching and frame coherence

Realtime ray tracing requires high computational power. One of the methods which

could be used to reduce computational expences is caching. Results of the tracing proce-

dure could be stored in a ray cache which will reduce a response time for future requests.

The main question is how to build an adequate and efficient caching strategy. Several au-

thors were selected which used caching techniques in their work (Chan [7], Debattista [9],

Popov [42], Ruff [46], Tole [50], Scherzer [48]).

The goals of the study:

1. find ”postulates“ for ray caching (how ray caching could be performed in general)

2. the seek strategy shall exploit ray coherence in rapidly changing environments

3. the seek strategy shall be implementationally gpu-compatible

The following literature review attempts to find such a strategy.

In a research by Chan et al. [7] the ray coherence is exploited to accelerate a sound

rendering process in an interactive environment. The article postulates the following prin-

ciples for the ray caching.

1. Rays with the same geometric properties (starting point, directions) as contained in

cache do not have to be traced again.

2. To maintain the intersection history objects are subdivided into discrete patches.

3. The cache represents a graph with object patches as nodes and rays as edges.

Once a ray hits a patch in the cache, the whole intersection history for the given patch

be taken which replaces costly intersection tests. Since this article is important for the

research, it is necessary to highlight some implementation details here.

Patch subdivision An object is subdivided into small patches so that two rays hitting the

same patch are considered have the same intersection points. Angular ray directions are

quantized

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-25-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

Coherence Intra-frame coherence occurs when several rays share the same path inside

one frame. Inter-frame coherence occurs when several rays share parts of paths contained

in the cache

Ray cache The cache consists of a tree and a graph attached to tree. Every node of the

tree is identified by a complex index (object, patch, patch, ..., division)

Purging The cache is purged according to Least Recently Used strategy using timestamp

Source movement When a ray source changes its position all cache entries connected

with it are removed from the cache.

Chan got significant performance improvements using the ray cache. The method was

beneficial in multi-user interactive environments with high ray coherence. Hovewer, the

method has several disadvantages. Firstly, the method is implemented on cpu using so-

phisticated data structures which will be hardly efficient on gpu. Secondly, the method

is limited to step - by - step movements with high correlations between frames. Thirdly,

the cache is purged when a source changes its position, it means that in succeeding frames

the cache cannot be reused. Nevertheless, the article states fundamental ideas for the ray

cache implementation.

Debattista et al. [9] used several techniques based on irradiance caching [54] in render-

ing dynamic scenes with global illumination [52]. The main contribution of the article is

detection of invalid ray paths after geometric transformations. Authors considered five

cases for invalidation of their instant cache.

Case 1 Occlusion of a light path by moving object (occlusion of a secondary light source)

Case 2 Deocclusion of a light path by moving object (deocclusion of a secondary light source)

Case 3 Occlusion of a visibility ray by moving object

Case 4 Deocclusion of a visibility ray by moving object

Case 5 Cache sample lies on a dynamic object

Figure 2.1 gives a summary of all cases. Overall, Debattista used caching for calculation of

a radiance integral where the cache stores illumination instead of visibility. Secondly, the

method is limited to static scene with moving objects. However, some of the ideas for ray

purging (ray invalidation) could be used in this work as well.

Popov et al. [42] in their work exploited an idea of lightcuts [53]. Authors introduced a

fundamental point-to-point visibility caching algorithm with could be incorporated in any

ray tracer. Also they developed an adaptive quantization scheme which helps to control

trade-off between performance and quality. The algorithm was implemented on gpu using

hash table which is of a particular interest for the research.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-26-2048.jpg)

![2.1. Ray caching and frame coherence

Figure 2.1.: The five cases that invalidate the instant cache [9]

One of the main entities in Popov’s work is a binary visibility function. It is defined as

V (X, Y ) =

®

1 if X and Y are mutually visible

0 otherwise

(2.1)

The visibility function is approximated using quantization of path domain and mapping

K( ¯pe, ¯pl) → N which relates a pair of surface points to a unique cluster. The quantized

visibility function is defined as

¯V ( ¯pe, ¯pl) ≈ V C

(K( ¯pe, ¯pl)) (2.2)

The quantization error is controlled using equation

|A( ¯pe)||A(¯pl)| =

(CE)2

P( ¯pe)P(¯pl)Np

(2.3)

The figure 2.2 summarizes the concept.

To define K(.), the scene surface is divided into a set of virtual multi-resolution, overlap-

ping and differently oriented voxel grids. For vertex X with N(X) a quantized direction

is defined as

ωq

=

ñ

N(X) + 1

2

CN

ô

, dz =

2ωq

CN

− 1 (2.4)

K(.) returns a tuple of 14 integers: 3 for the orientation of X, 3 for the coordinates contain-

ing X, and 1 for the grid resolution R( ¯pe); integers for Y are chosen analogously.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-27-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

Figure 2.2.: Similar paths are grouped together and share the same visibilty query [42]

The concept is illustrated by the figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3.: Visibility domain quantization [42]

Results of the visibility queries are stored in a hash table. To define a particular bin,

researchers calulate a 32 bit key k(j) from j = K(.) and use modulo division k(j) mod CT

where CT is the hash table size. They also employ a direct-mapped cache which does not

resolve collisions simply overwriting the data. One important implemenation detail is that

the algorithm uses a counter which controls how many threads in the warp need to trace

rays. If the counter is less then some predefined threshold, the local state of each thread is

saved in a small pre-warp queue and and the rays are not trace immediately. Whenever

the number of threads in the queue exceeds 32, the tracing is performed. This helps to

utilize a gpu performance and load it uniformely.

For the method assessment Popov uses three metrics: Quality metric, Performance met-

ric and Cache performance metric. As a quality writers employ a predictive QMOS pro-

posed by Mantiuk et. all [30]. As a performance estimation it is taken a shadow ray re-

duction and the total frame rendering time. The cache performance was measured using

ratio

(1 − HitRatio) = MissRatio = 1/(RayDirection + 1) (2.5)

Results show significant shadow ray reduction, up to 50×, preserving image quality with

QMOS above 77%. The total rendering speedup varies from 2.5× to 6.7× for different

scenes.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-28-2048.jpg)

![2.1. Ray caching and frame coherence

All in all, the article is very valuable. Firstly, it gives a theoretical background for the

visibility caching. Secondly, the approach described could be used in rapidly changing

environments as in car driving since the quantization allows to exploit the inter-frame co-

herence when trace paths change entirely from frame to frame. Thirdly, the algorithm is

efficiently implemented on gpu using hash table and direct mapping which makes caching

very fast. On the other hand, quantization introduces too much parameters (14) which

makes hash table indexing a bit complicated using digest, prepending and modulo op-

erations. The higher performance makes memory utilization higher. On the hand, fast

changing scenes impose much stress on gpu buffers which could potentially cause mem-

ory destruction.

Ruff et al. [46] investigate the question of using caching textures for real time tracing

in OptiX. For each reflective object of the scene, researchers generate a set of 6 caching

textures. Before tracing a ray leaving the object the algorithm queries color information for

that ray in the caching textures. If the information is available it is taken from the cache,

otherwise the tracing procedure takes place. Authors introduce geometrical scheme how

reflection rays are saved in the textures. Results shows that the method produces pictures

that are visually equivalent to the reference images. A speed up achieved comparing to

conventional ray tracing varies from 2% to 168% depending on the number of additional

reflective objects.

Developers themself mention in their article that their method is tailored to static scenes

with convex objets and auto-reflection features. However, the idea of using the cubic box

as caching structure could be beneficial in this work as well.

Tole et al. [50] examine in their paper how to build a system for interactive computa-

tion of global illumination[52] in dynamic scenes. The system stores illumination samples

generated by pixel based rendering algorithms and then applies interpolation between

samples using graphics hardware. The shading cache represents a hierarchical patch tree

with every patch containing the last computed shading values for its vertices. The patch

could be used in three ways, either its value is used for interpolation or the patch could

be refined further or its value is updated. If the cache grows above the threshold, patches

which are not longer seen on the scene removed together with their children using ”not

recently used” strategy. When an object on the scene or light moves the patch values are

recalculated using ”age priority“. Comparison with other cache rendering systems, shows

that the system suits best for applications like interactive lighting design and modeling.

Altogether, the system likewise Debattista [9] uses illumination cache, spatial coherence is

exploited using interpolation, while temporal coherence maintained by reusage of patches

from previous frames. All this makes the approach practically useless in this study.

Work by Scherzer [48] is notes for the course with the same name: ”Exploiting Tempo-

ral Coherence in Real-Time Rendering”. He determines temporal (frame) coherence (TC)

as “the existence of a correlation in time of the output of a given algorithm”. He further

states that the coherence could be used to accelerate a given algorithm making it incre-

mental in time and for quality improvement by taking into account results obtained in the

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-29-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

previous frames. Next, Scherzer describes the Reverse Reprojection Cache which reuses

shading results from previously rendered frames. The basic idea of the method is to allow

renderer to use a shading information which is available for a given point in the previous

frame buffer. In order to do this Scherzer introduces a reverse reprojection operator. For

refreshing the cache, the screen is divided into n parts which are updated in a round-robin

fashion. The method shows good acceleration results for a few pixel shaders. It is used for

stereoscopic rendering, simulation of motion blur and depth of field effects, view frustum

culling techniques and others. Again, this method is basically designed to being used as

shading/illumination cache, it could be used for exploiting the temporal coherence in ob-

ject space in culling techniques but this does not help much in our task. The formulation

of the temporal coherence could be used to calculate how good frames correlate with each

other.

Upon the whole, the objectives are achieved. It has been selected the main strategy for

caching proposed by Chan et al. [7]. Based on work by Popov [42] the strategy could be

extended using the quantization (Chan also uses it intoducing divisions). Also the system

could be efficiently implemented on gpu using hash table and bin indexing. Some of the

policies for ray purging could be used from work by [9].

2.2. GPU data structures

In this subsection, it is given an overview for gpu data structures using book ”GPU Gems

2“ [31] and articles by Lefohn [28], Foley [13] and Prabhakar [34].

The main goal of the review to find an efficient parallel gpu data structure for the ray

cache implementation.

Lefohn, in chapter 33 of ”GPU Gems 2”[31] explains how fundamental data structures

are implemented using GPU programming model. According to Lefohn, GPU has the

following data structures: multidimensional arrays, static and dynamic sparse structures.

Multidimensional arrays 2-D textures with nearest-neighbour filtering are the substrate

on which most of the GPGPU structures are built. All multidimensional array use

address translation to convert N-D array address to 2-D texture. GPU implementa-

tion of the address translation suffers from limitations on floating-point addressing.

1-D array 1D arrays are implemented by mapping the data to 2D texture. Currently,

a maximum width for a 1D texture is 227 = 134, 217, 728 [37]. Each time an

element in a 1D array accessed by a GPU program, the address is translated

into a 2D texture indeces.

2-D array 2D arrays are represented as 2D textures. Their maximum size is limited

by the GPU driver.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-30-2048.jpg)

![2.2. GPU data structures

Figure 2.4.: Representation of 1D arrays on GPU

3-D array 3D arrays can be implemented in three ways: as 3D textures, as several

levels of 2D textures or directly mapped to single 2D textures. Every implemen-

tation has its pluses and minuses. For example, the simplest 3D implementation

does not have an address translation and for this structure could be used native

GPU trilinear filtering to create high-quality data renderings. As a disadvan-

tage, this structure requires many passes to write to the whole array.

structures There are two possible solutions: a stream of structures and a structure of

streams. The stream of structures is a problematic solution because every member

of structure has a different stream index and they cannot be easily updated. Con-

trariwise, in the structure of streams, a separate flow is created for every structure

member.

sparse data structures Implementation of sparse data structures as lists, trees or sparse

matrices is problematic on the GPU. Firstly, because this involves writing to a com-

puted memory address (scattering). Secondly, traversing of such data structures in-

volves an inhomogenous number of pointer dereferencing operations to access data

which has difficulties based on processing properties of SIMD architecture. Elements

which are processed by single SIMD should contain exactly the same instructions.

static sparse structures The static sparse structures are not changed during the

GPU computation. All of these structures contain one or more levels of indirec-

tion.

There are two methods for solving the problem of irregular access in these pat-

terns: the first one is to divide the whole frame into blocks where all blocks

have the same random access model and can be handled together. The second

method is to have a stream to process one member from its scheduled list per

render passage.

dynamic sparse structures Dynamic sparse data structures is a very active research

area. One of two noticable works are Purcell et al. 2003 [44] and Lefohn at al

[17], [27].

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-31-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

Figure 2.5.: Purcell et al. 2002 [45]. Sparse Ray-Tracing Data Structure

A photon map [44] is a cache which stores intersection points and incoming di-

rections for light packets called photons.There are two techniques which allow

to build the photon map on the GPU. The first one computes addresses and data

for writing then it performs a scattering by performing parallel sorting opera-

tions on the buffers. The second method uses vertex processor.

Lefohn [27] created efficient dynamic data structure on GPU for implicit sur-

face deformation. He solves scattering problem by sending small messages to

the CPU when the GPU needs to be updated. The structure uses the blocking

strategy.

Weber et al. [55] presented efficient implementation for sparse matices on

GPU in solving of sparse linear systems in dynamic applications.

performance considerations In case of dependent memory reads there is a possibility

to create a memory-incoherent memory accesses. It could be prevented by creation

of coherent blocks of similar computations, small lookup tables and minimization of

dependency levels. Another important performance concerns include optimization

of computational frequency on the GPU, program specialization and a proper use of

pbuffers.

Foley and Sugerman [13] presents a GPU implementation for kd-tree traversal algorithm

suitable for raytracing but they build data structures on the CPU. This is of no interest for

the work.

Lefohn et al. [28] presented an abstract generic template library for complex random-

access data structures on the GPU. The structures, a stack, an octree, a quadtree are build

using standard library components. Firstly, ptx programs generated by nvcc compiler

should conform to restrictions imposed by OptiX API. This makes impossible usage of

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-32-2048.jpg)

![2.3. GPU programming model and memory types

some CUDA libraries. Secondly, we do not need so complicated data structures as octrees,

on the other hand functions for construction and utilization of data primitives as 1D, 2D,

3D arrays are built in OptiX API. All these make usage of the library unreasonable.

Lock-free data structures represent a certain interest in this work. Prabhakar and Chaud-

huri [34] evaluate their performance on the GPU. They consider lock-free linked list [18],

hash table, skip list [18] and priority queue [18]. The data structures are evaluated using a

mix of add, delete and search operations for different key ranges. For the lock-free linked

list, the GPU implementation has a moderate speedup up to 7.4 times for small to medium

key ranges comparing to the CPU implementation. The hash-table on the GPU outper-

forms the CPU implementation of the same structure in the all key ranges with the maxi-

mum speedup at 11.3. GPU realization of the lock-free skip-list is beneficial for small and

medium key ranges with the maximum speedup at 30.7. For the lock-free priority queue,

GPU benchmarks have the same pattern as for the skip-list with the maximum speedup

of 30.8. They close discussion by comparing performance of the GPU implementations of

hash-table and linked list. The hash-table is 36 to 538 times better then the linked-list. They

conclude that the GPU helps the hash-table to reveal its concurrent potential making it the

best data structure for arbitrary key ranges.

To sum up, in this subsection, it is considered problems of building data structures on

the GPU. It has been mentioned that the question of sparse data structures construction is

challenging task. However, many developers and researchers have already contributed to

this area. A lock - free data structures is of a particular interest since they offer efficient

GPU implementation. The hash table proved to be the best data structure of the afore-

mentioned due to its constant performance benefits and design well-suited for usage in

multithreaded GPU applications.

2.3. GPU programming model and memory types

In this section, it is given an overview of CUDA C programming model [37] and consid-

ered different types of GPU memory.

2.3.1. GPU programming model

Kernels

CUDA C allows a programmer to write C functions (kernels) which during invocation are

executed in parallel by N different CUDA threads. A kernel is defined using the global

identifier. The quantity of CUDA threads which are going to execute the kernel for the

given call is defined using a new syntax <<<...>>>. Each CUDA thread is given a unique

thread id which is accessible in the kernel body using the built-in threadIdx variable.

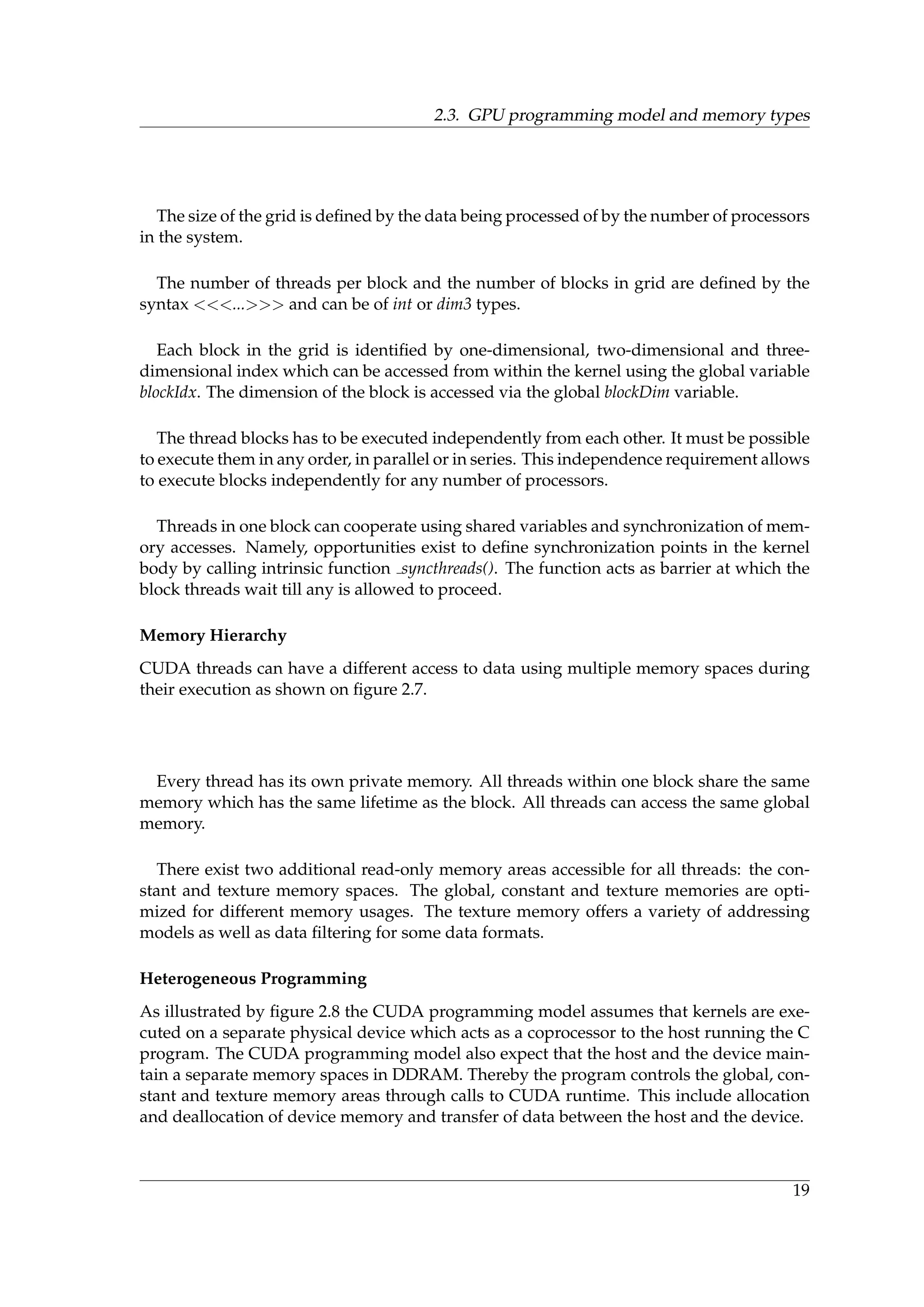

Thread hierarchy

For convenience, threadIdx is a three component vector so that every thread can have a 1-

dimensional, 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional index to form a 1-dimensional, 2-dimensional

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-33-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

or 3-dimensional block.

The thread id and it index inside the block is put in one-to-one correspondence using

the following equations:

for the 1D block: thread ID = x where (x) is the thread index

for the 2D block of size (Dx, Dy): thread ID = (x + yDx) where (x, y) is the thread index

for the 3D block of size (Dx, Dy, Dz): thread ID =(x + yDx + zDxDy)

There is a limit in the number of threads combined into one block since all the threads

should be processed by one processor core thus sharing the same memory. Presently, mod-

ern GPU allows to have blocks with a maximum of 1024 [37] threads per block.

Nonetheless, a kernel can be executed by a multiple blocks so the total number of

threads executing the kernal equals to the number of blocks multiplied by the number

of threads in the block. The blocks are organized in one-dimensional, two-dimensional,

three-dimensional grids as illustrated by figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6.: Grid of thread blocks [37]

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-34-2048.jpg)

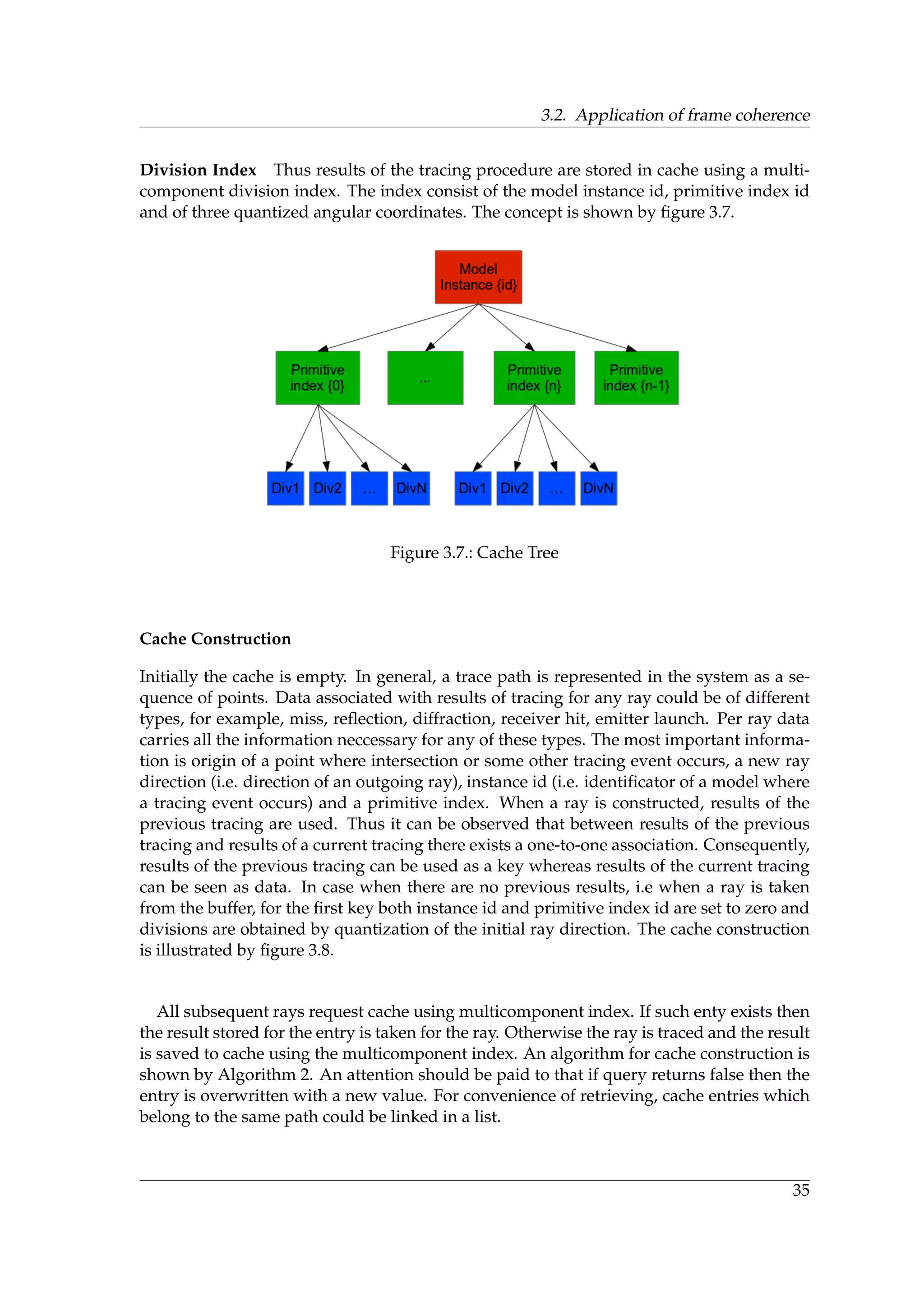

![2. Literature review

Figure 2.7.: Memory hierarchy [37]

Serial code is executed on the host while parallel code is executed on the device.

Compute capability

Compute capability is defined by major and minor revision numbers. Devices that share

the same major revision number are of the same core architecture. The minor revisions

represent incremental improvement of the core architecture, possibly including new fea-

tures.

2.3.2. GPU memory types

In this subsection, it is given an overview of different GPU memory types.

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-36-2048.jpg)

![2.3. GPU programming model and memory types

Figure 2.8.: Heterogeneous programming [37]

Device memory accesses

An istruction which accesses a memory address could be performed multiple times de-

pending on the distribution of memory addresses across the threads within one warp.

How the distribution influences performance is peculiar to each memory type and de-

scribed in the following subsections. For instance, for the global memory, the rule of thumb

is that the more scattered addresses are the less performance is.

Global Memory

Global memory exists in device memory which is accessed using 32-, 64- and 128-byte [37]

memory transactions. These transactions should be naturally lined up: only 32-, 64- and

128-byte segments of device memory that are lined up to their size (i.e. the first address of

a segment is a multiple of its size) can be read or written by these transactions.

When a warp executes an istruction that accesses the global memory, it joins all memory

addresses for all threads within one warp into one or more memory transations depending

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-37-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

on the size of word accessed by each thread and distribution of the memory accesses across

the threads. The more transactions are necessary the more unused words are transferred

in addition to those words which are actually accessed by the threads reducing instruction

throughput.

How much transations are necessary and what the throughput of the device is fully

depends on the computing capability of the device. For devices of compute capability 1.0

and 1.1 [37] requirements to get any coalescense are very high. They are more relaxed for

devices with higher compute capability. For devices of compute capability 2.x and higher

[37] the memory transactions are cached so that data localization is used to reduce impact

on the throughput.

In order to maximize the throughput of the global memory it is necessary to maximize

the coalescing by:

• Following the most optimal patterns for devices with computing capabilities of 1.x,

2.x and 3.x [37]

• Utilizing data types which comply with requirements of data size and alignment

• Padding of data in some cases when, for example, accessing two-dimensional arrays

Size and Alignment Requirement

Instruction in global memory support writing and reading of words with size of 1,2,4,8 or

16 bytes [37]. Any access to data in the global memory compiled to a single istruction in

global memory if and only if the data size does not exceed these numbers and the data is

naturally aligned. If the requirements are violated then muliple instructions with different

access patterns are which hinder data coalescing.

The alignment is automatically done for built-in data types like char, short, int, long,

longlong, float, double like float2 or float4 [37].

For structures, the size and alignment requirements can be fullfilled using special speci-

ficators like align (8) or align (16).

Any variable which is located in the global memory is returned by a driver routine for

memory allocation or by runtime API aligned to at least with 256 bytes.

Reading of not naturally aligned 8-byte or 16-byte words [37] could lead to incorrect

results, a special attention should be paid to maintain alignment of a value or an array of

values of these types. This is a typical error which occurs when memory allocation for

multiple arrays using common calls to function cudaMalloc or cuMemAlloc are replaced by

allocation of a single large block in memory partitioned into multiple arrays. In this case

the starting addresses of the arrays are shifted with regard to the initial address of the

block.

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-38-2048.jpg)

![2.3. GPU programming model and memory types

Two-Dimensional Arrays

A common access pattern is when a thread with index tx, ty tries to access an element in

2D array of width width using the following mapping BaseAddress + width ∗ ty + tx. In

order these accesses are fully coalesced, the width of the thread block as well as the width

of the array should be be a multiple of the warp size.

Local Memory

Only automatic variables could be placed to the local memory. The automatic variables

are:

• Arrays for which cannot be detemined that they are indexed with constant values

• Large structures of arrays which otherwise consume too much register memory

• Any variable if kernel uses more registers then available

The local memory is located in device memory and as a consequence has a high latency

and a low bandwidth as the global memory and is a subject to the same requirements for

memory coupling. However the local memory is organized in that way that consecutive

32-bit words accesses are performed by threads with consecutive IDs. Therefore the ac-

cesses are coalesced as long as all threads in one warp access the same relative address.

For devices with compute capability 2.x and higher [37], all accesses to the local memory

are cached in the same way as accesses to the global memory.

Shared Memory

Shared memory has much lower latency and much higher instruction throughput then lo-

cal or global memory because it is placed directly on the chip. To achieve high bandwidth,

the shared memory is divided into equally-sized memory modules called banks which can

be accessed simultaniously. Thus processes of reading and writing to memory which refer

to locations seating in n memory banks can served simultaneously resulting in n times

overall bandwidth increase.

If two threads access addresses in the same bank then serialization is necessary. These

requests are divided into as many conflict-free queries as necessary. If thus n queries oc-

curs, the initial memory request is said to cause n-way bank conflicts. In order to maximize

performance it is necessary to minimize bank conflicts. This is specific to different device

types because of mechanisms of mapping memory addresses to memory banks.

Constant Memory

Constant memory lies in device memory and cached in constant cache for devices with

compute capabilities of 1.x and 2.x [37]. For devices with compute capability 1.x [37] a

request to constant memory for a warp is divided into two requests for an every half-

warp which then served independently. These requests are further divided to subrequests

depending on the number of memory addresses contained in the initial query. The overall

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-39-2048.jpg)

![2. Literature review

throughput is reduced by the number of subrequests. These subrequests are served at the

cache bandwidth in case of cache hit or at device bandwidth otherwise.

Texture and Surface Memory

Texture and surface memory reside in device memory and are cached in texture cache,

thus the cost of texture and surface memory access equals to cost of reading from the

device memory in case the data is not in cache, otherwise it costs reading from the texture

cache. The texture cache is optimized for 2D spatial localization, threads of the same warp

located in 2D space near each other achieve the best performance. Therefore the cache is

designed for streaming ingress with constant latency. Thus a number of cache hits reduces

the DDRAM bandwidth demand but not the fetch latency.

Reading of device memory using texture or surface memory has a number of benefits

which makes it advantageous alternative comparing to reading the device memory from

global or constant memory:

• If accesses to global or constant memory are carried out with violation of perfor-

mance rules, a higher bandwidth can be achieved providing that there is a localiza-

tion in texture fetches or surface reads.

• Operations of addresses calculation are performed outside of the kernel using special

units

• Packed data can be transferred to separate variables using single operation

• 8 or 16-bit integers can be cast to 32 floating-point values in the range of [0.0,1.0] or

[-1.0, 1.0] [37]

2.4. Ray Reordering

In this subsection, some ray reordering techniques are considered using articles by Garanzha

and Loop [14] and Moon et al. [35].

The goal here is to find suitable for the task ray reordering methods.

Garanzha and Loop [14] use ray sorting to boost efficiency of ray tracing by revealing

of coherence between rays and reducing a number of execution branches within SIMD

processor. For the ray sorting they propose a method based on compression of key-index

pair. Then the compressed data is sorted and decompressed.

The sequence of key-index pairs is generated by using a ray id as the index and a hash

value for the given ray as the key. Coordinates of ray sources are quantized using virtual

uniform 3D grid within the volume bounding the scene. Ray directions are also quan-

tized using virtual uniform grid. Using these grids, authors calculate ray ids which then

merged into a 32-bit hash value. Rays which have the same hash value are considered to

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-40-2048.jpg)

![2.4. Ray Reordering

be coherent in space. Then compressed data is sorted using radix sort. After the data is de-

compressed, packet ranges are extraced uing the same compression procedure. Once the

ranges are extracted, the next step is to create a frustum for each packet. The frustums are

traversed using the breadth-first algorithm. Next, the active frustums are decomposed into

chunks of 32 rays max analogously to CUDA warp. This eliminates execution branches

within a CUDA warp. Primary rays are indexed and sorted according to a screen-space

Z-curve. Binary BVH is build on CPU using binning algorithm. The algorithm is com-

pared with Depth-first algorithm for the ray tracing. They get significant performance

improvements for soft shadow rays at 1024 × 768 × 16 samples. Comparing to CPU, GPU

implementation is 4× faster. However, authors assume that memory consumption could

be sufficient. Also the bad case for the algorithm if one frustum captures all of the BVH

leaves which could cause very unbalanced workload.

Moon et al. [35] implemented the ray tracing with cache-oblivious ray reordering. For

the ray sorting, authors introduce a Hit Point Heuristic. A hit point is computed as the first

intersection point between the scene and a line starting from the ray origin pointing in the

ray direction. After this, points are reordered using a space-filling curve (Z-curve). Dur-

ing implementation stage, Hilbert curves were also considered but they gave only slight

performance benefits (e.g. 2%) while having much more complex implementation. The

ray tracer is implemented on the CPU. The method is tested for path tracing as well as

for photon mapping. For the path tracing, their method achieves a significant 16.83 times

performance improvement compared to without reodering. For the photon mapping, the

method in different configurations gives from 3.77 to 12.28 times performance improve-

ment. Rays reordering is also the cause of a higher cache utilization. Also ray reodering

based on Hit Point Heuristic shows better performance then ray reodering based on ori-

gin + direction reordering. However, authors mention that there is no guarantee that the

method will improve performance of the ray tracing because of the overhead.

Altogether, the goal is accomplished, it have been considered methods for ray reordering

using different techniques. Hash values for the rays could be generated using ray origin

and direction quantization as well as based on quantization of spatial information like hit

points coordinates. Rays according to their hash values could be sorted in different ways.

For example, using radix sort or space-filling curves. Also, in considered articles authors

report about significant performance improvements for tracing with ray sorting.

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-41-2048.jpg)

![3. Problem and Solution

3.1. An experiment with dimensionality of context launches

The first problem that is considered is the problem of how dimensionality of a computa-

tional problem affects efficiency of ray tracing.

3.1.1. Problem Description

The problem described in Redmine ticket #155 ”Experiment with dimensionality of context

launches“. The ticket has the following content:

”Chapter 9.Performance Guidelines” of OptiX Programming Guide [38] states that the

maximum coherence between threads of a tile is achieved by choosing an appropri-

ate dimensionality for the launch. For example, common problems with 2D images

has 2D complexity. Thus the problem is reduced to the determination of the launch

dimension and investigation of how this affects efficiency.

3.1.2. Theory

To describe the solution to the problem it is necessary to start from definitions for space-

filling and Hilbert curves.

Space-filling Curve

The space-filling curve is defined in the following way [3]:

Given a mapping f : I → Rn, then the corresponding curve f∗(I) is called a space-filling

curve, if the Jordan content of f∗(I) is larger then 0.

Hilbert Curve

The Hilbert curve is defined as [3]:

• each parameter t ∈ I = [0, 1] is contained in a sequence of intervals

I ⊃ [a1, b1] ⊃ ... ⊃ [an, bn] ⊃ ...

where each interval results from a division-by-four of the previous interval

• each such sequence of intervals can be uniquely mapped to a corresponding se-

quence of 2D intervals (subsquares)

• the 2D sequence of intervals converges to a unique point q in q ∈ Q = [0, 1] × [0, 1] -

q is defined as h(t)

f : I → Q defines a space-filling curve, the Hilbert curve.

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-43-2048.jpg)

![3. Problem and Solution

Grammar for 2D Hilbert Curve

Grammar for 2D Hilbert curve can be constructed in the following way [3]:

• No-terminal symbols: H, A, B, C, start symbol H

• terminal characters: ↑, ↓, ←, →

• productions:

H ← A ↑ H → H ↓ B

A ← H → H ↑ H ← B

B ← C ← H ↓ H → B

C ← B ↓ H ← H ↑ B

• replacement rule: in any word, all non-terminals have to be replaced at the same

time → L-System (Lindenmayer)

Arrows describe the iterations of the Hilbert curve in ”turtle graphics“[43]. Figure shows

a sample 2D Hilbert curve generated using the grammar.

Figure 3.1.: An example of 2D Hilbert curve

Grammar for 3D Hilbert Curve

L-Systems in three dimensions could be described using ”turtle graphics” [43]. The ba-

sic idea is to represent the turtle orientation in 3D space using a set of vectors [ ˆH, ˆL, ˆU]

representing the turtle’s heading, left direction and upward direction accordingly. Vectors

[ ˆH, ˆL, ˆU] form an orthonormal basis. Spatial rotations of the turtle can be described:

[ ˆH , ˆL , ˆU ] = [ ˆH, ˆL, ˆU]R (3.1)

where R is a 3 × 3 rotation matrix. Rotations by angle α around vectors ¯U,¯L and ¯H are

represented by the following matrices:

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-44-2048.jpg)

![3.1. An experiment with dimensionality of context launches

Figure 3.2.: Controlling turtle in 3D [43]

RU (α) =

cos(α) sin(α) 0

−sin(α) cos(α) 0

0 0 1

RL(α) =

cos(α) 0 −sin(α)

0 1 0

sin(α) 0 cos(α)

RH(α) =

0 0 1

0 cos(α) −sin(α)

0 sin(α) cos(α)

(3.2)

The following symbols determine turtle’s orientation in space:

+ Turn left by angle δ, using rotation matrix RU (δ)

- Turn left by angle δ, using rotation matrix RU (−δ)

& Pitch down by angle δ, using rotation matrix RL(δ)

∧ Pitch up by angle δ, using rotation matrix RL(−δ)

Roll left by angle δ, using rotation matrix RH(δ)

/ Roll right by angle δ, using rotation matrix RH(δ)

— Turn around, using rotation matrix RU (180◦)

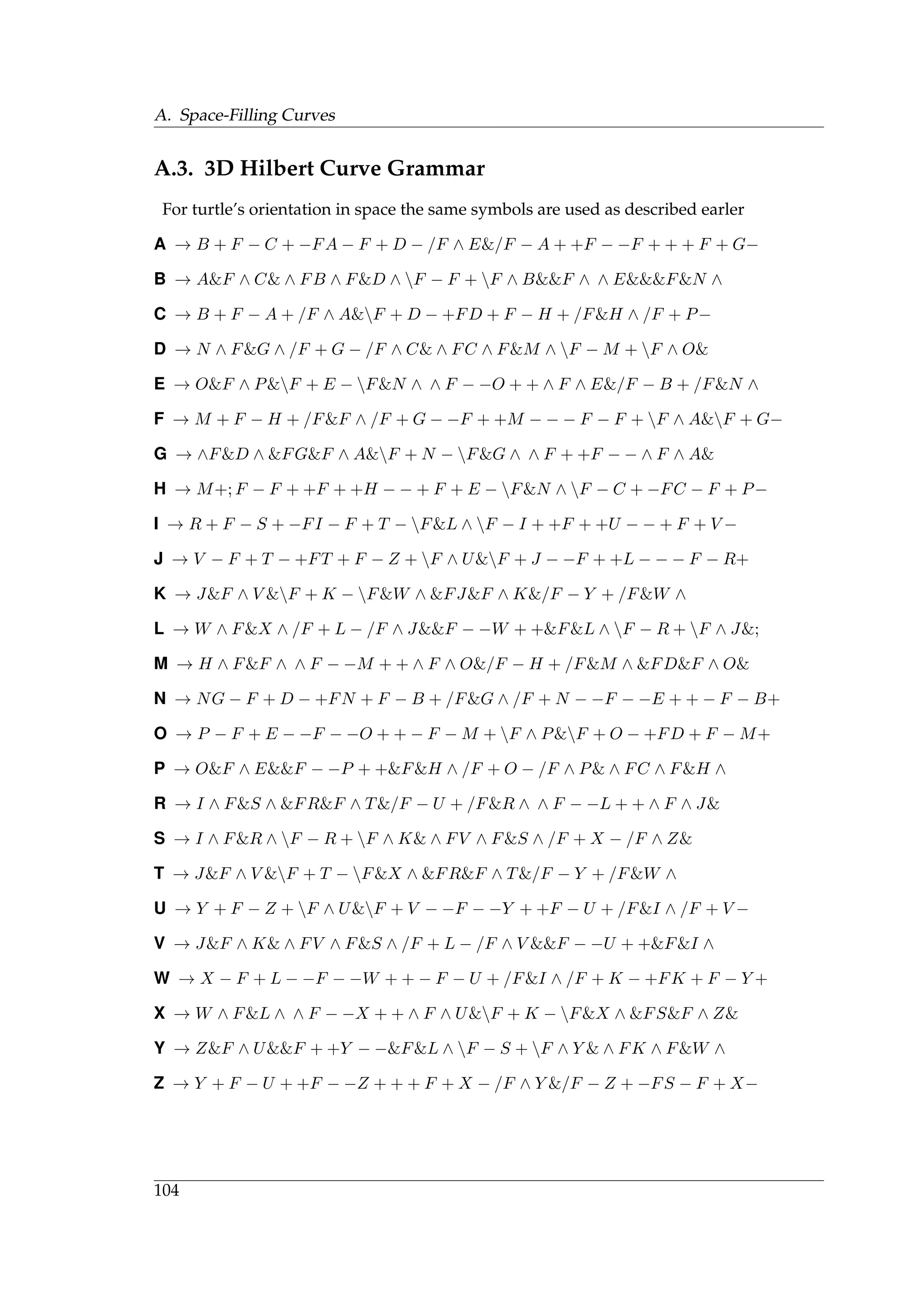

An interested reader could find a grammar for 3D Hilbert curve in appendix A.3.

Z Curve

Z-curves are defined in terms of Morton codes [24]. In order to calculate Morton codes it is

necessary to consider a binary representation of point coordinates in 3D space, as shown

by figure 3.3. Firstly, for each coordinate, the binary code is expanded by insertion of two

additional ”gaps“ after each bit. Secondly, the binary codes of all coordinates are joined

(interleaved) to form one binary number. If thus resulting codes are sorted in ascending

order, this will determine the sequence of z-curve in 3D space (the left part of figure 3.3).

The sorting could be performed using radix sort.The expansion and interleaving of bits

could be done efficiently by utilizing the arcane bit-swizzling properties of integer multi-

plication. A curious reader will find a listing in appendix A.1.

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-45-2048.jpg)

![3. Problem and Solution

Figure 3.3.: Generation of Morton codes [24]

3.1.3. Problem Solution

The problem solution could be sketched in the following way:

1. Sort ray buffer according to spatial ray coordinates

2. Initialize the sorted buffer with the context depending on the dimensionality

For 1D, –

For 2D, map 1D indeces to 2D array structure using 2D Hilbert curve

For 3D, map 1D indeced to 3D array structure using 3D Hilbert curve

Next will be discussed in more details points of this sketch.

Sorting

Histogram and Hilbert Curve The first approach is to generate indices for every ray in

3D and sort them according to Hilbert curve.

Ray indices Rays generated for the wavetracer represent uniformely distributed

points on a unit sphere. Their coordinates could be quantized. The quanti-

zation is the same as the redistribution of rays on a three-dimensional spatial

data structure (a histogram) according to their directions. For each element in-

side the ray buffer could be generated indices depending on the number of bins

in the histogram. Using these indices the ray could be added to a bin of the

histogram. A pseudocode for the algorithm is shown by Algorithm 1. A geo-

metrical interpretation of the algorithm is shown by figure 3.4.

Hilbert curve Once, the data structure is obtained, it could be sorted using a 3D

Hilbert curve or, which is the same, mapped from 3D to 1D data structure. The

sorted buffer could be used directly for the context initialization. The Hilbert

curve generated for 16 × 16 × 16 bins is shown by figure 3.5.

Morton codes and Radix Sort The second approach is a logical continuation of the pre-

vious. Morton codes sort rays according to their spatial neighborhood in z-order.

Using morton codes, rays could be sorted with radix sort.

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-46-2048.jpg)

![3.2. Application of frame coherence

Algorithm 1 Algorithm for histogram generation

for all element in Buffer do

x0 ⇐ (element.x + 1)/2)

y0 ⇐ (element.y + 1)/2)

z0 ⇐ (element.z + 1)/2)

x ⇐ floor(x0 ∗ bin num/2)

y ⇐ floor(y0 ∗ bin num/2)

z ⇐ floor(z0 ∗ bin num/2)

list ⇐ histogram[x][y][z]

v.x ⇐ x0

v.y ⇐ y0

v.z ⇐ z0

list.pushBack(v)

histogram[x][y][z] ⇐ list

end for

Morton codes Efficient implementation for generation Morton codes was shown

in the previous subsections. The figure 3.6 shows a pattern generated by the

algorithm when sorting rays.

Radix Sort CUDA already has an efficient implementation for this algorithm.

Transformation between Spacial Structures

To experiment with dimensionality, it is necessary to transform spatial structures from 1D

to 2D or 3D data structures. This also could be achieved using Hilbert curves.

Mapping from 1D to 2D The sorted buffer could be mapped from 1D to 2D using 2D

Hilbert curve.

Mapping from 1D to 3D The mapping between 1D and 3D could be achieved using 3D

Hilbert curve.

Implementation details will be discussed in the appropriate chapter.

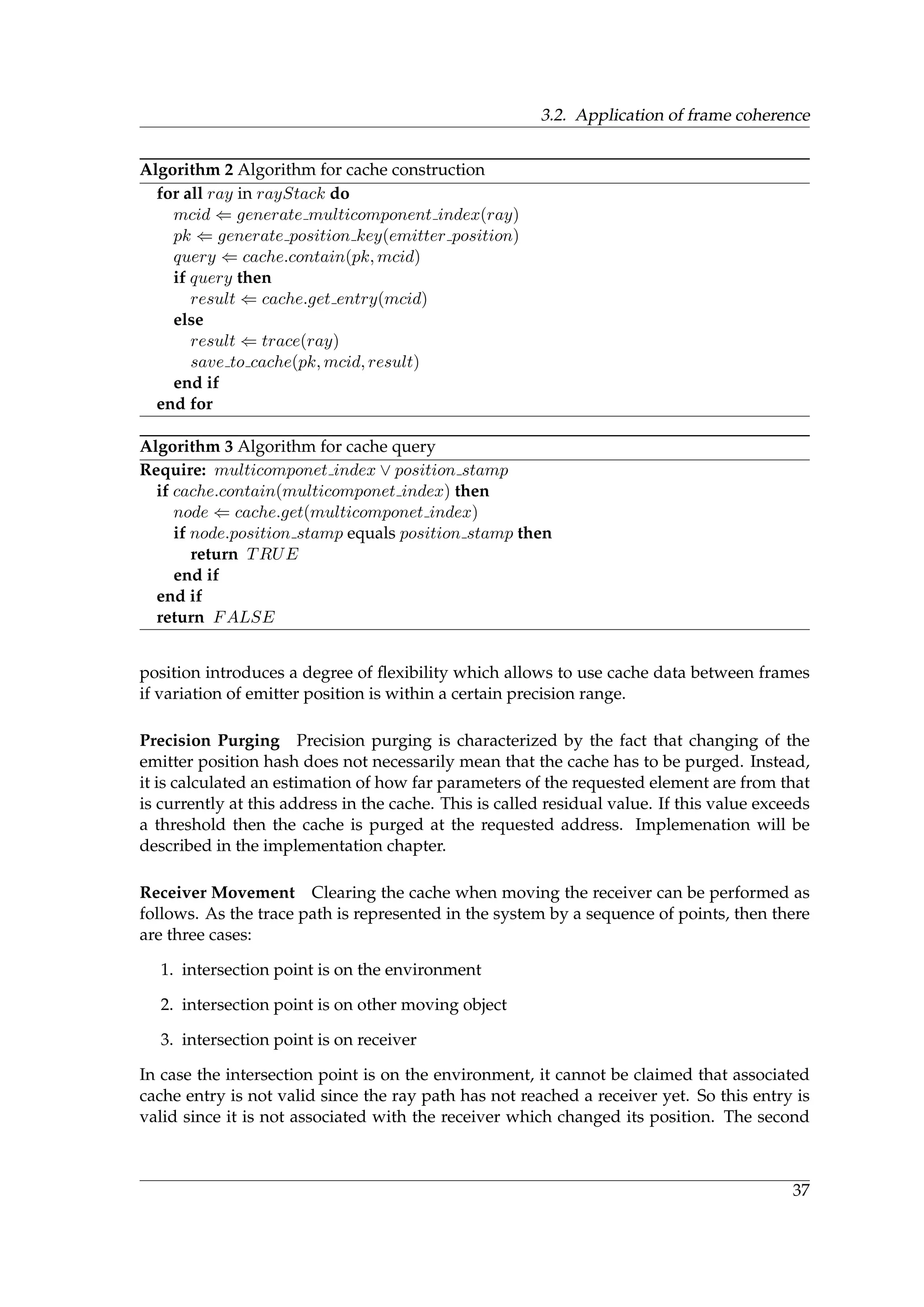

3.2. Application of frame coherence

The second problem is an investigation of influence of frame coherence on the wavetracer

performance.

3.2.1. Problem Description

The task is formulated in Redmine ticket # 218 ”Exploit frame coherence”. The task has

the following objectives:

1. Find types of coherence which exist in the system

a) Measure coherence

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-47-2048.jpg)

![3. Problem and Solution

Figure 3.4.: Uniformely distributed rays & histogram bins

2. Find schemas(algorithms) which allow to exploit them

3. Propose efficient implementation for the algorithms

4. Implement the proposed solution

5. Measure performance

6. What are the costs for coherence utilization in the system?

In the following subsections, the first two points will be considered.

3.2.2. Coherence

According to ”A Dictionary of Statistics” [51], coherence is a “term used to describe the

resemblance between the fluctuations displayed by two time series; an analogue of corre-

lation”.

Innerframe Coherence

In the context of the given work, the innerframe coherence means that there is a correlation

between results of ray tracing inside one frame. Rays with high coherence could be com-

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-48-2048.jpg)

![3.2. Application of frame coherence

Figure 3.5.: Hilbert curve generated for 16 × 16 × 16 bins

bined into groups. Inside these groups it necessary to trace only one ray [42]. Questions

which could be posed here:

1. How to know what rays have to be coalesced into one group?

2. How results of the tracing are to be stored in the cache?

3. How to calculate the error which introduces this approach?

Intraframe Coherence

The intraframe coherence means that there is a correlation between results of ray tracing

procedure for different frames. A result of the tracing procedure for any ray could be

stored in cache and used in the next frames. Questions which could be posed here:

1. How to measure coherence between frames?

2. How to know what data could be reused in the next frames?

3. What caching strategy to choose to purge the cache?

Coherence Measurement

Both innerframe and intraframe coherence could be measured using Pearson product cor-

relation coefficient [32].

rxy =

N

i=1(xi − ¯x)(yi − ¯y)

»

n

i=1(xi − ¯x)2 n

i=1(yi − ¯y)2

(3.3)

Where x and y are two random variables with N observations.

For the innerframe coherence could be used autocorrelation function [32].

rk =

N−k

i=1 (xi − ¯x)(xi+k − ¯x)

n

i=1(xi − ¯x)2

(3.4)

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-49-2048.jpg)

![3. Problem and Solution

Figure 3.6.: Z-curve

The quantity rk is called the autocorrelation coefficient at lag k. Calculation of these values

will be covered in more detail in the chapter dedicated to testing.

3.2.3. Formulation of Caching Scheme

In the Literature Review it has been done already a survey of caching schemas. Using

ideas stated by Chan [7] it is possible to build a caching system for the given task.

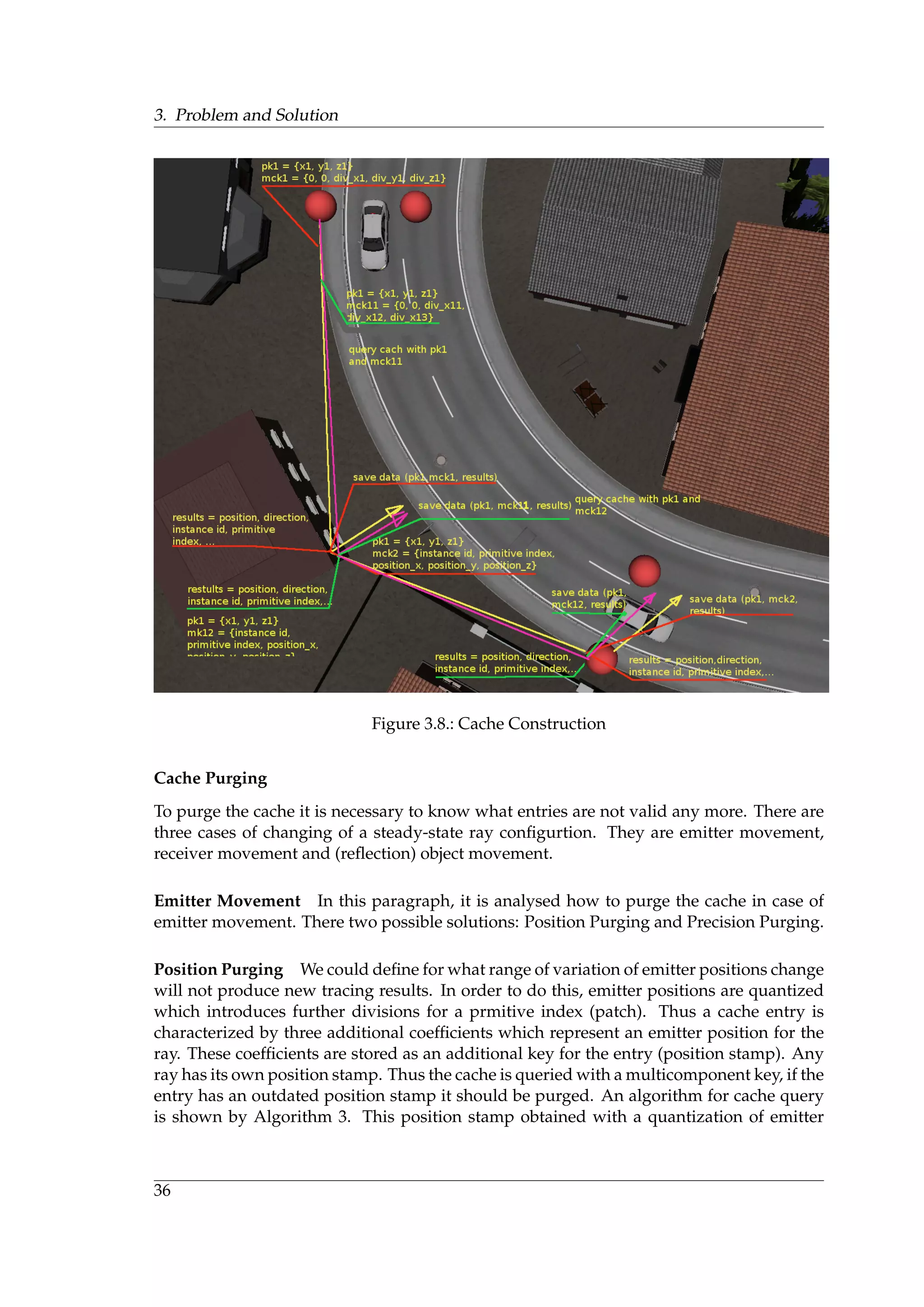

Cache Tree

In Chan’s [7] work, each object consists of several surfaces, each surface is divided into

several levels of patches and every patch is further quantized depending on angular values

of incident rays.

Objects In this work, there is only one type of objects: a model instance. Models are

distinguished using their ids which are defined in the configuration file. An environment

is also loaded as a model instance which usually has -1 as id. So roots of cache trees could

be featured using these identificators.

Patches There is a natural division of such objects into patches which are called primitive

indices. These primitive indices introduce patches of native precision for the objects. So

results cached for the given object could be discriminated using these indices.

Divisions Patches or primitive indices are responsible for spatial accuracy. However,

rays have to be distinguished also by angular precision. Angular values of incident rays

represent spatial coordinates within a sphere of unit length. These coordinates are also

quantized using some big number introducing quantization precision. Quantized coordi-

nates introduce divisions which further dinstinguish incident rays.

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-50-2048.jpg)

![4. Analysis and Modelling

Figure 4.3.: Saving data

2. If such trees can be efficiently constructed, how to maintain them?

3. How to implement a fast data search in such trees?

In our case, the cache trees cannot be implemented directly as they described by Chan [7],

firstly, because it requires a dynamic allocation of memory which is disabled in OptiX. Sec-

ondly, a search of elements in such data structures is challenging. In order to make it more

convenient, it is necessary to maintain additional data structures performing indexation.

Assuming all these, construction of such trees will be difficult.

Binary Tree

The first idea that comes is to use a binary tree. It has an easy construction and main-

tainance. Complexity of search in binary tree is O(log(n)). An object hierarchy could be

maintained using hashing of multicomponet indices. On the other hand, hash values could

be used to determine a total ordering of elements of the tree. Selection of an appropriate

hash function is a separate issue which will be regarded later. The problem with dynamic

allocation could be solved using a buffer with predefined elements. The tree is illustrated

using the figure 4.4.

However, the binary tree has one major defect: all elements of the tree have to be added

using the root element. The root element has to contain a counter which indicates the next

element in the buffer of predefined elements. In case of massively parallel computations,

GPU streams have to access the counter successively in order to provide data consistency.

This counter introduces the main bottleneck of the binary tree.

Chained Hash Table

A natural solution to the problem described in the previous paragraph is to constuct trees

in parallel. This resolves collisions of streams trying to access the counter and reduces the

waiting time in the queue. The streams are distributed by various root elements depending

on the hash value of added element. Such data structure is called a chained hash table [29].

It is more preferred then the binary tree, however, performance analysis of the chained

table shows that access to the root elements (buckets) and to chained elements of the table

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-62-2048.jpg)

![4.2. Frame Coherence

Figure 4.4.: Binary Tree

have different times. This difference overall reduces the table performance making it not

very profitable. Also since the element buffer has a fixed size, it is necessary to reserve a

certain number of elements for each bucket. This creates a fragmentation of the element

buffer. The data structure is illustrated by figure 4.5.

Implementation of the chained hash table is described in Implementation of Data Struc-

ture 5.2.2. Performance analysis is described in the Testing chapter 6.

Open-Addressed Hash Table

Further improvement of the data structure is permission of the direct access to elements of

the table. This solution has several benfits:

1. Further reduction of stream collisions

2. Absence of buffer fragmentation

3. A fast access to elements

Direct mapping allows to further reduce collisions of GPU streams. Absence of trees con-

struction solves the probem of buffer fragmentation. Direct access to buffer elements pro-

vides a possibility of fast read/write cache operations implementation. Nevertheless, there

exists an implementation pitfall connected with OptiX buffer which will be described in

the implementation subsection.

Implementation of the open-addressed hash table [29] is described in Implementation of

Data Structure subsection 5.2.2. Performance analysis is described in the Testing chapter

6.

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-63-2048.jpg)

![4.2. Frame Coherence

The first condition is necessary in order to distribute elements accross all buckets in uni-

form manner so that all the buckets contain approximately equal number of elements. The

second condition ensures that any element is identified in unique way.

However, based on the task solution approach, it is necessary to add another condition,

namely that keys with similar parameters should have close hash values. The question is

whether the conditions one and two are compatible. This should not be a problem because

rays are already uniformely distributed on a unit sphere.

Hash Function with Uniform Distribution

The key represents an array of integers. It is necessary to generate a hash value based on

the array. The code for such function could be taken, for example, from Morin [36]. Listing

4.2 shows the code.

Listing 4.2: Hash function for integer array

unsigned hashCode ( ) {

long p = (1L<<32)−5; / / prime : 2ˆ32 − 5

long z = 0x64b6055aL ; / / 32 b i t s from random . org

int z2 = 0x5067d19d ; / / random odd 32 b i t number

long s = 0;

long zi = 1;

for ( int i = 0; i < x . length ; i ++) {

/ / reduce to 31 b i t s

long long xi = ( ods : : hashCode ( x [ i ] ) * z2 ) >> 1;

s = ( s + zi * xi ) % p ;

zi = ( zi * z ) % p ;

}

s = ( s + zi * (p−1)) % p ;

return ( int ) s ;

}

In this listing, x is an array of integers. Integers are hashed using a multiplicative hash

function with d = 31 to reduce a hash code to 31 bits representation. This is done in order

additions and multiplications can be carried out using a 63-bit arithmetic. Probability for

two sequences to contain have the same hash code is defined as [36]

2

231

+

r

(232 − 5)

(4.1)

Hash Function Preseving Data Locality

Space filling curves again could be used to generate codes for multicomponent keys. The

key represents an integer array with 5 componets: instanceId, primitiveIndex, ,div x,

div y, div z. Listing 4.3 shows how the Morton Codes generator could be altered for 5D

[20].

51](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-67-2048.jpg)

![4. Analysis and Modelling

Listing 4.3: Morton Codes generator for 5D

unsigned int SeparateBy4 ( unsigned int x ) {

x &= 0 x0000007f ;

x = ( x ˆ ( x << 16)) & 0x0070000F ;

x = ( x ˆ ( x << 8 ) ) & 0x40300C03 ;

x = ( x ˆ ( x << 4 ) ) & 0x42108421 ;

return x ;

}

MortonCode MortonCode5 ( unsigned int x ,

unsigned int y ,

unsigned int z ,

unsigned int u ,

unsigned int v ) {

return SeparateBy4 ( x ) |

( SeparateBy4 ( y ) << 1) |

( SeparateBy4 ( z ) << 2) |

( SeparateBy4 (u) << 3) |

( SeparateBy4 ( v ) << 4 ) ;

}

SeparateBy4 inserts four blank bits between every two bits in the binary representation of

an integer. MortonCode5 interleaves binary representations using shift and or operations.

Double Hashing

In open-addressed hash tables, it is also used a mixed hash function [29]. The function for

double hashing is defined as:

h(k, i) = (h1(k) + i ∗ h2(k)) mod m (4.2)

where h1 and h2 are two auxilliary hash functions and i goes from 1 to m − 1 where m is

the number of positions in the table. In this work, however, it is used a simpler equation

where i and m are set to 1. Justification for this is that probing of hash table is not used,

i.e. insertion code does not look for unoccupied places in the table. Instead entire range of

hash function values is mapped directly to a discrete set of buffer indices. The mapping

function discribed in the next subsection.

4.2.5. Selection of Mapping Function

A mapping function associates a range of hash function values to the set of buffer indices.

The following formula performs the mapping:

f(h) = (1.0 + h/INT MAX) ∗ m/2; (4.3)

where h is a hash value, INT MAX is a constant denoting the maximum integer in a

system, m is the hash table size. The size of INT MAX is defined by ANSI standard. For

unix 32-bit systems it is 2,147,483,648 [56]. Thus for m = 500000 a range of hash values for

one bucket is approximately 8590.

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-68-2048.jpg)

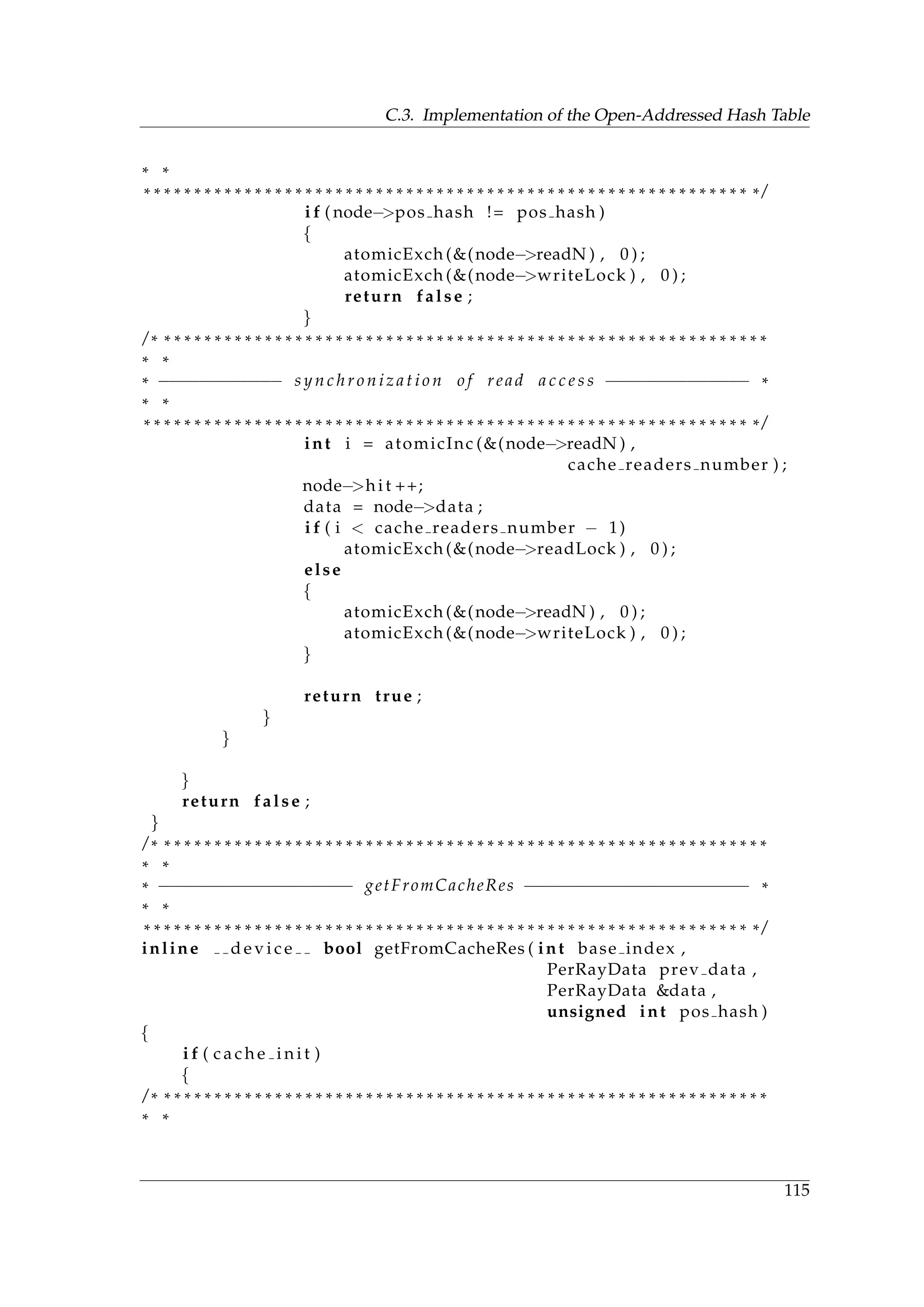

![4.2. Frame Coherence

4.2.6. Selection of Synchronization Mechanism

Selection of synchronization mechanism depends on the data structure which is going to

be implemented. In case of chained hash tables, it is possible to use a lock-free synchro-

nization [34]. Synchronization of reading/writing access in open-addressed hash tables

could be implemented using atomic locks [47].

Lock-free Synchronization

In lock-free style of programming [40], at least one thread always do a progress. All threads

try to write their results to the concurrent data structure. On failure, a thread repeats the

operation. For synchronization, atomic operation are used usually. The following code

shows the atomicCAS operation how it is defined in CUDA [40].

Listing 4.4: atomicCAS [40]

int atomicCAS ( int *p , int cmp, int v){

exclusive single thread

{

int old = *p ;

i f (cmp == old ) *p = v ;

}

return old ;

}

The next listing shows insertion of element to a lock-free linked list.

Listing 4.5: Insertion to lock-free linked list [40]

void i n s e r t ( ListNode mine , ListNode prev )

{

ListNode old , link = prev−>next ;

do{

old = link ;

mine−>next = old ;

link = atomicCAS(&prev−>next , link , mine ) ;

}while ( link != old )

}

Idea behind the lock-free data updates is that on every new cycle it is generated a new

value based on current data. Then performed an atomicCAS operation trying to change

the current data to the new value. If the operation unsuccessful it is repeated again.

Atomic Lock Synchronization

In the locking style of programming [40], all threads are trying to get the lock. One thread

aquires the lock, does its work and release the lock and so on. The next listing shows a

mutex synchronization using atomic locking.

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-69-2048.jpg)

![4. Analysis and Modelling

Listing 4.6: Addition using atomic lock [40]

int locked = 0;

bool try lock ( )

{

int prev = atomicExch(&locked , 1 ) ;

i f ( prev == 0)

return true ;

return false ;

}

bool unlock ( )

{

int prev = atomicExch(&locked , 0 ) ;

i f ( prev == 1)

return true ;

return false ;

}

double atomicAdd ( double * data , double val )

{

while ( try lock ( ) == false ) ;

double old = * data ;

* data = old + val ;

unlock ( ) ;

return old ;

}

54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-70-2048.jpg)

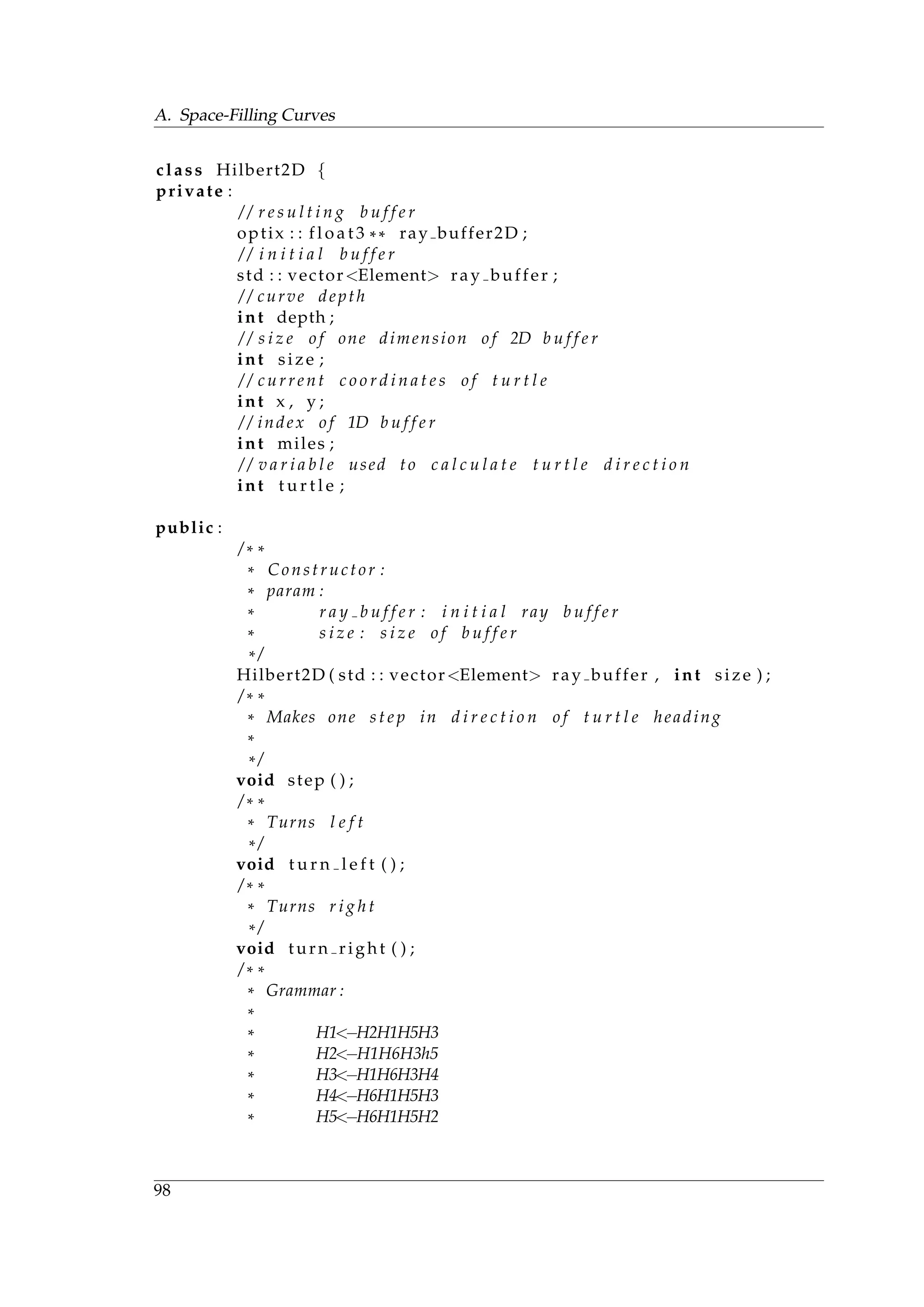

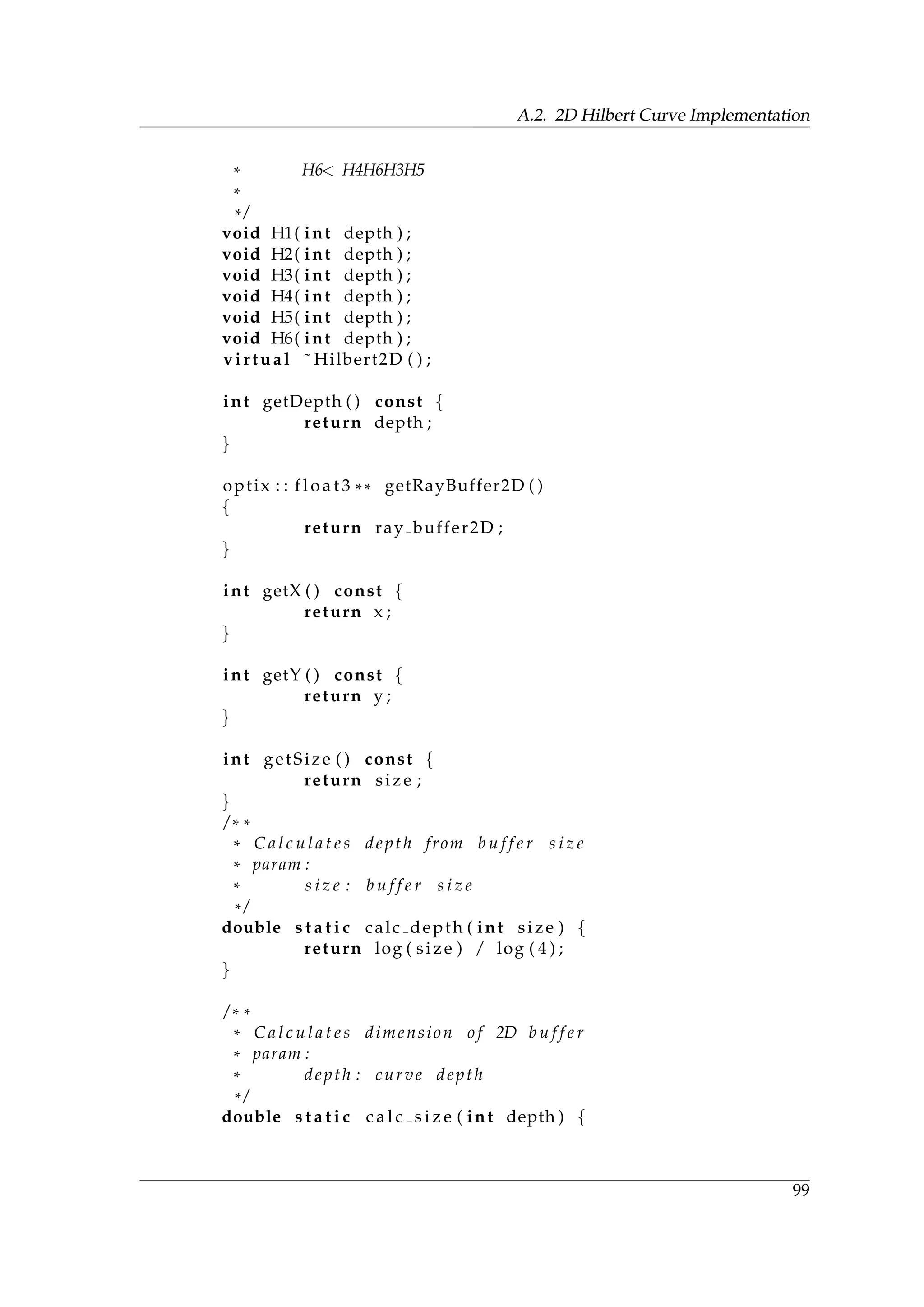

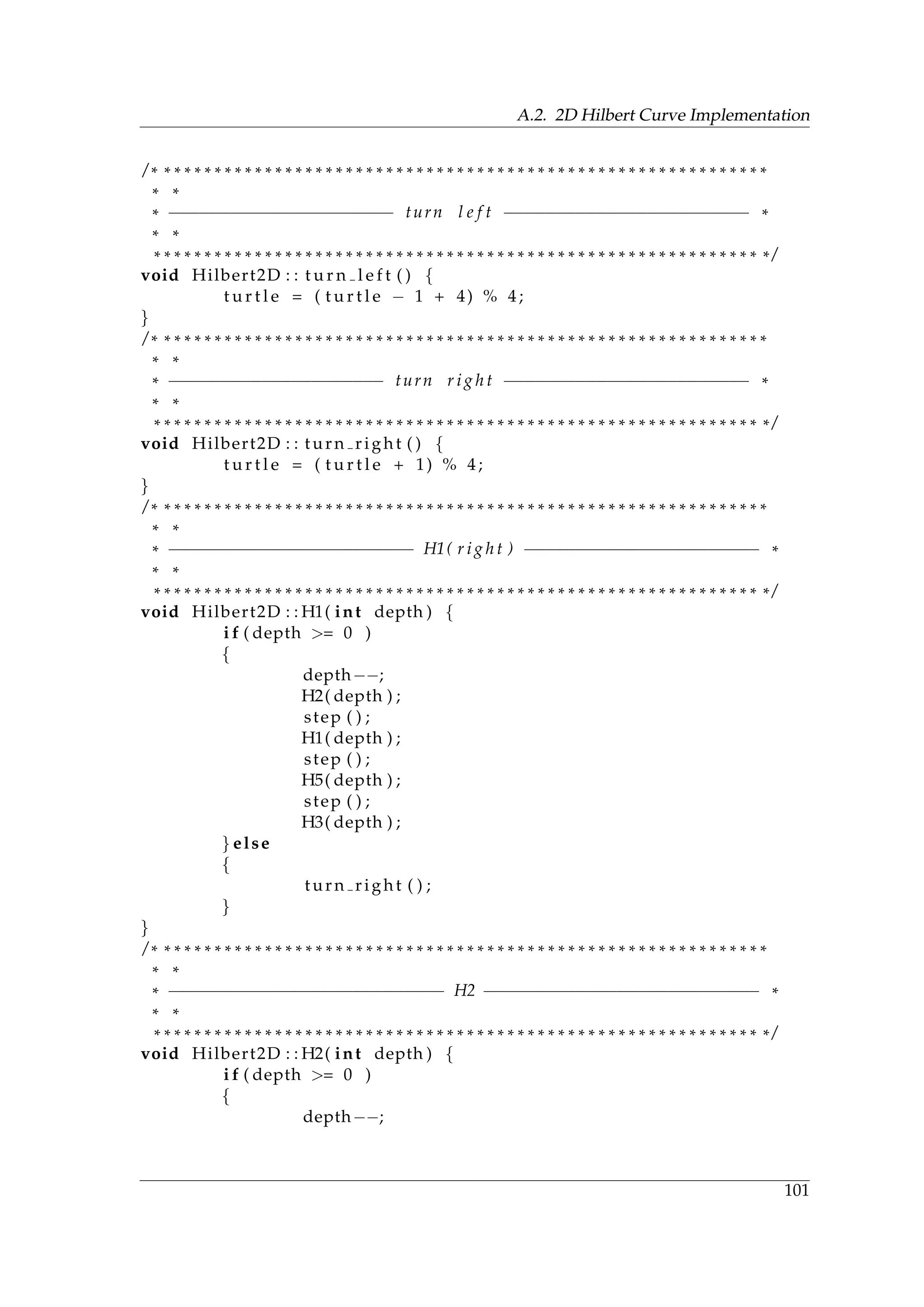

![5. Implementation

5.1. Implementation of Ray Reordering

During the research stage, it have been implemented 2D and 3D Hilbert curves, Z-curve

and the ray histogram. The implementation is performed on the CPU side, because the task

that is to explore how the ray sorting affects efficiency. On the basis of investigation results,

it is found that the most efficient solution is a combination of Z-curve and Radix sort. An

implementation of Z-curve has been described in the previous chapter and CUDA has

already an efficient implementation for Radix sort algorithm. Thus there exists a standard

GPU implementation. Results of the benchmarking are described in the next chapter.

Hilbert Curves

2D Hilbert Curve The curve is implemented using a turtle graphics with at most one

turn after a step [21]. An interested reader could find the implementation in appendix A.2

3D Hilbert Curve Implementation of the 3D Hilbert curve on the CPU is a straightfor-

ward. It follows the syntax given in appendix A.3. Showing the implementation would be

tedious for the reader.

Z Curve

Implementation for Z-curve strictly follows the algorithm given in appendix A.1.

Ray Histogram

Ray histograming is described by algorithm 1. The implementation exactly corresponds to

the algorithm.

Radix Sort

The algorithm for Radix sort has already an efficient implementation in CUDA, see, for

example [33].

5.2. Implementation of Frame Coherence

In this section, it is described an implementation of frame coherence according to selected

data model 4.2.3 and data structure 4.2.2.

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-71-2048.jpg)

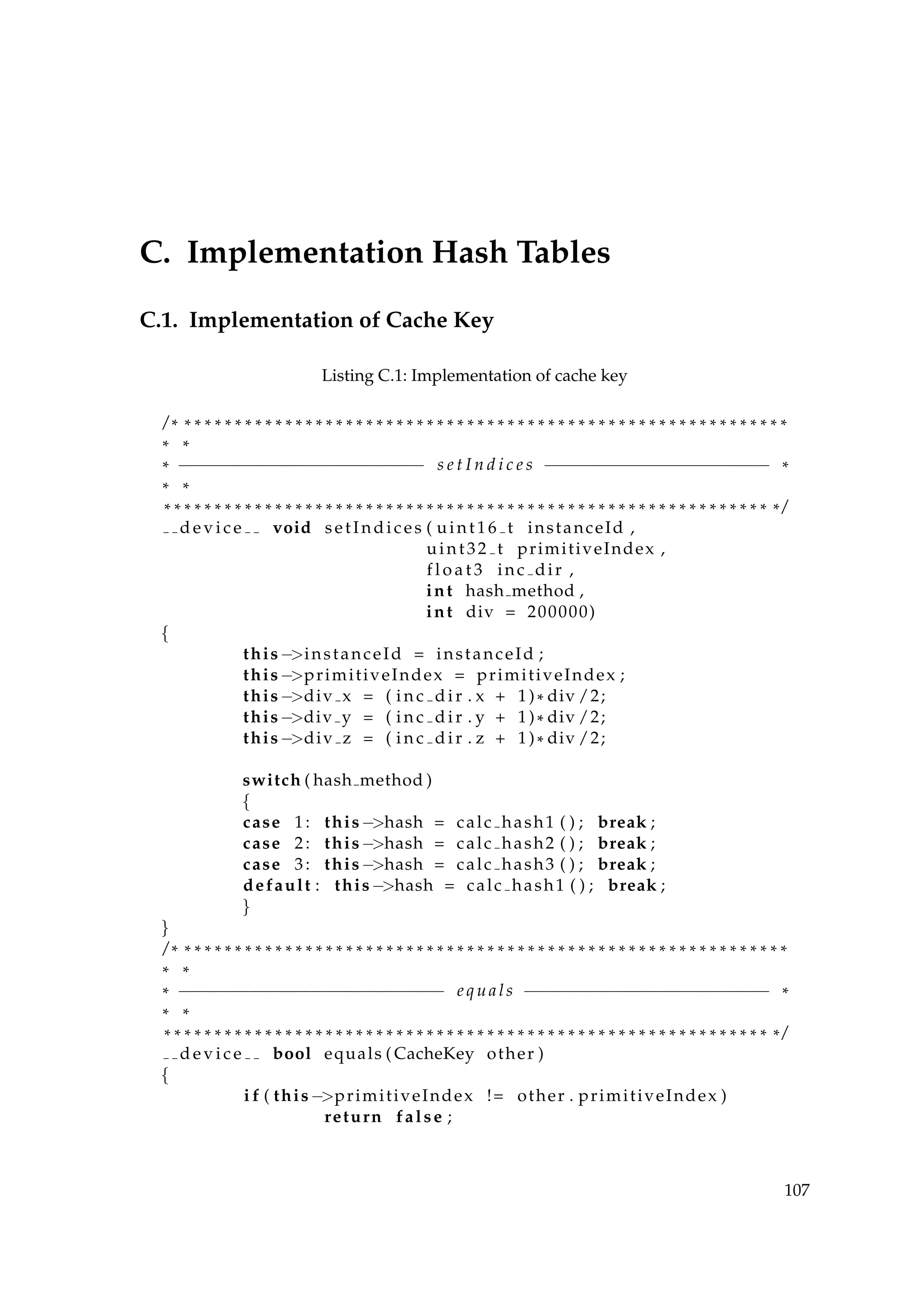

![5. Implementation

5.2.1. Implementation of Data Model

The implementation of data model includes implementation of CacheKey and CacheNode.

Cache Key

CacheKey is a data structure which contains parameters of a multicomponent key 3.2.3.

Interface

setIndices

device void setIndices(uint16 t instanceId, uint32 t primitiveIndex, float3 inc dir, int

hash method, int div)

Return value void

Parameters

instanceId : identificator of loaded model

primitiveIndex : identificator of mesh triangle

inc dir : a ray direction angle

hash method : id of hash function

div : quantization precision

Description Set the key members and calculate the hash value for the key data.

equals

device bool equals(Key other)

Return value boolean

Parameters

other : a key for comparison

Description Returns true if the key is equal to the key provided

calc hash1

device bool calc hash1()

Return value unsigned integer

Description Calculates a hash value from key members using uniform random distribu-

tion [36]

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-190806080204/75/Efficiency-Optimization-of-Realtime-GPU-Raytracing-in-Modeling-of-Car2Car-Communication-72-2048.jpg)

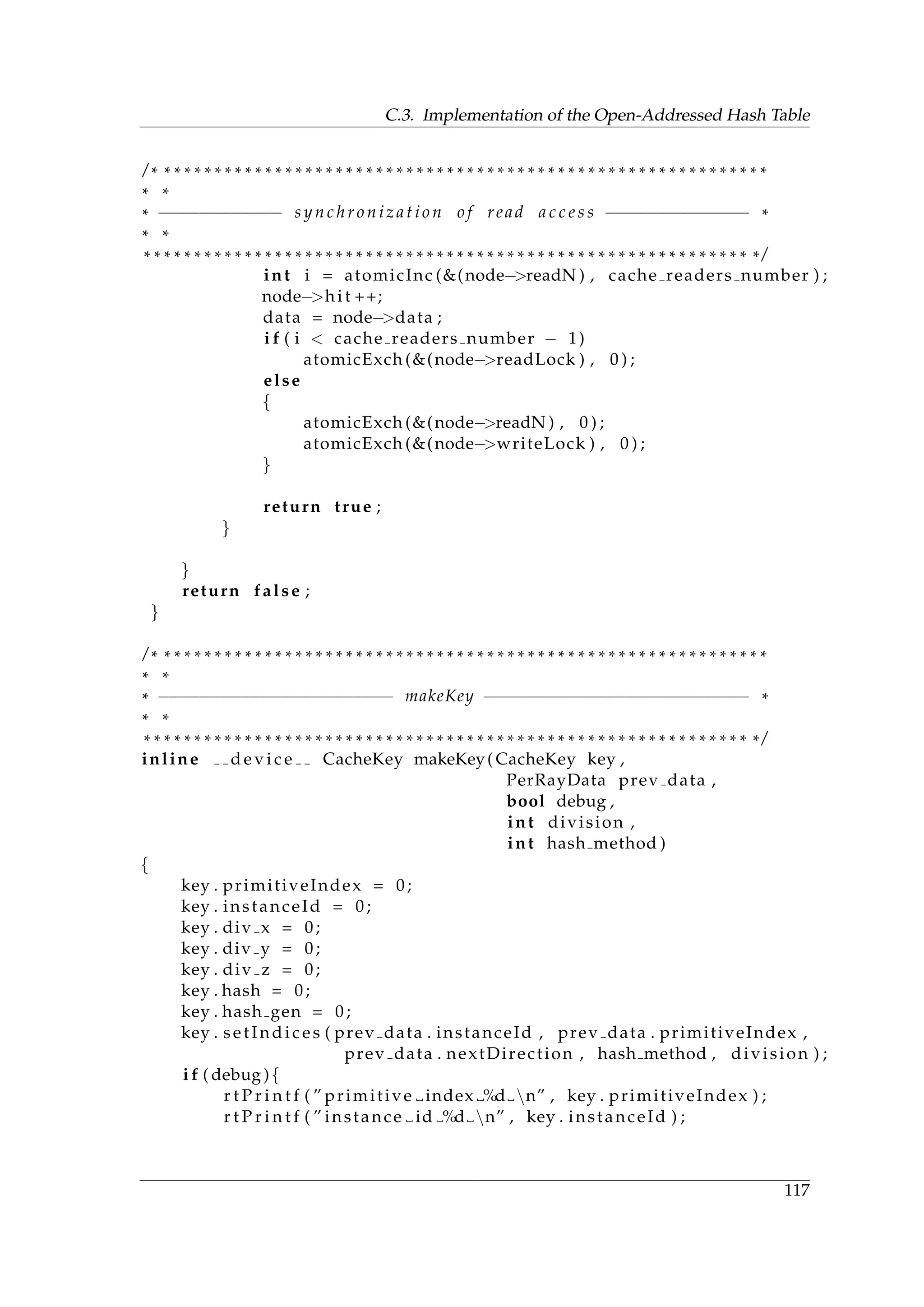

![5.2. Implementation of Frame Coherence

calc hash2

device bool calc hash2()

Return value unsigned integer

Description Calculates a hash value from key members using morton codes [20]

calc hash3

device bool calc hash2()

Return value unsigned integer

Description Calculates a hash value using a mix of two hashing functions [29]

separateBy4

device unsigned int separateBy4(unsigned int x)

Return value unsigned integer

Parameters

x : a number which binary representation to be shifted by 4

Description Separate bits by 4 bit places in binary representation of a number provided

in the method [20]

mortonCode5

device unsigned int mortonCode5(unsigned int x, unsigned int y, unsigned int z, unsigned

int u, unsigned int v)

Return value unsigned integer

Parameters

x : x coordinate

y : y coordinate

z : z coordinate

u : u coordinate

v : v coordinate

Description Constructs morton codes by interleaving x, y, z, u, v using oring and shifting

[20]