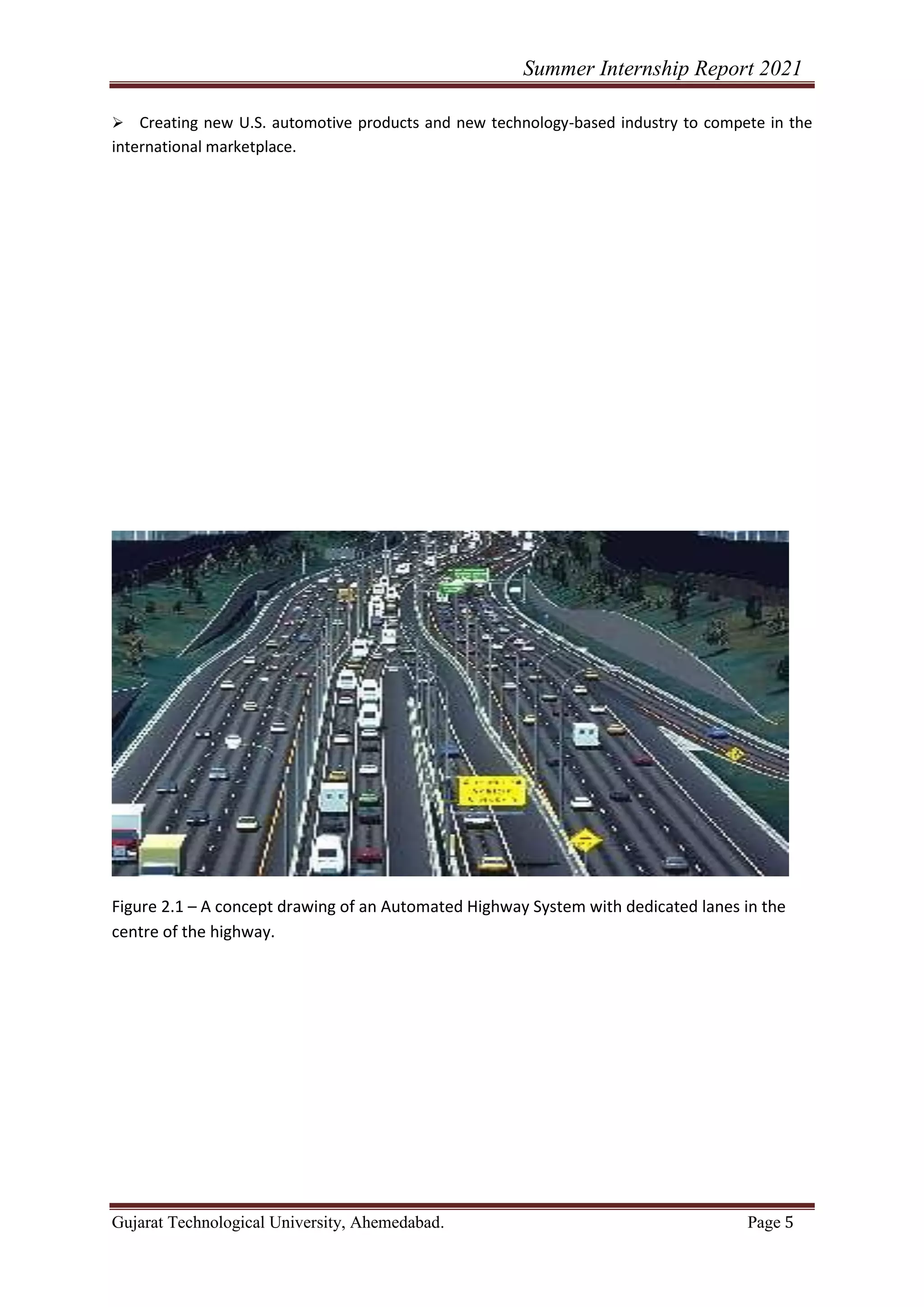

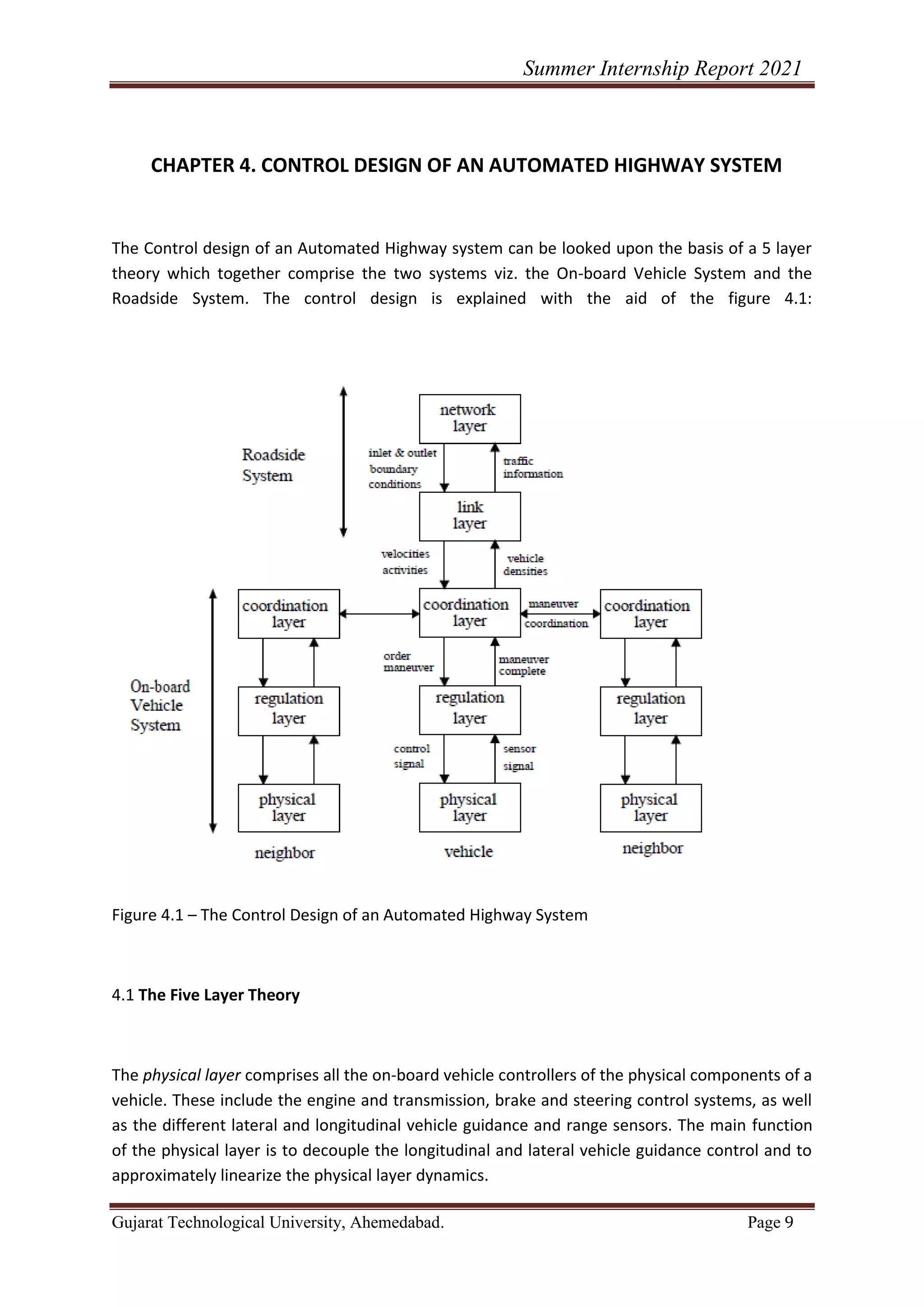

This document is a seminar report on automated highway systems presented by Samir Chauhan. It includes an introduction to automated highway systems, a discussion of major AHS goals like improving safety and mobility. It describes 5 concepts for AHS including independent vehicle, cooperative, infrastructure-supported, and adaptable concepts. It also discusses current vehicle technologies that could enable AHS like collision warning systems. The report outlines a 5 layer control design for AHS including physical, regulation, coordination, and link layers. It describes the on-board vehicle control system and roadside control system's roles in optimizing traffic flow and vehicle safety. The conclusion acknowledges more research is still needed due to lack of continued funding.