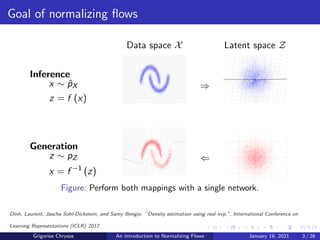

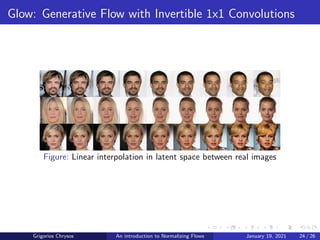

The document provides an introduction to normalizing flows, detailing how these invertible neural networks can transform data from a latent space to a data space and vice versa. It categorizes normalizing flows into several types, such as elementwise bijections, linear flows, and coupling flows, while also discussing practical considerations and limitations related to their implementation. Additionally, it covers applications in analyzing inverse problems and generative modeling, particularly highlighting the generative flow with invertible 1x1 convolutions (GLOW).

![Coupling flows

Let xA ∈ Rd and xB ∈ RD−d two disjoint partitions of x. Let

g : Rd → Rd be a bijective function, and φθ any arbitrary function.

The coupling flow realizes the mapping:

uA = g(xA, φθ(xB)), uB = xB (4)

where u = [uA, uB] is the output of the coupling layer.

The inverse of the coupling flow exists only if g is invertible. Then,

the inverse is:

xA = g−1

(uA, φθ(xB)), xB = uB (5)

Grigorios Chrysos An introduction to Normalizing Flows January 19, 2021 11 / 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-210623062100/85/An-introduction-on-normalizing-flows-11-320.jpg)

![Analyzing inverse problems

Let y ∈ RM be a measurement and x ∈ RD be the hidden variable in

the forward process y = s(x) with M < D.

Let z ∈ RK be a latent random variable, such that we want to learn a

function g with [y, z] = g(x).

Ardizzone, Lynton, Jakob Kruse, Sebastian Wirkert, Daniel Rahner, Eric W. Pellegrini, Ralf S. Klessen, Lena Maier-Hein,

Carsten Rother, and Ullrich Köthe. “Analyzing inverse problems with invertible neural networks.” ICLR 2019.

Grigorios Chrysos An introduction to Normalizing Flows January 19, 2021 19 / 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-210623062100/85/An-introduction-on-normalizing-flows-19-320.jpg)

![Analyzing inverse problems - Coupling layers

They define the following coupling layers with inputs [uA, uB]:

vA = uA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-210623062100/85/An-introduction-on-normalizing-flows-20-320.jpg)

![exp(sA(vA))+tA(vA) (6)

The inverse can be easily defined given inputs [vA, vB]:

uB = (vB−tA(vA))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-210623062100/85/An-introduction-on-normalizing-flows-22-320.jpg)

![is an elementwise product, and si , ti , i ∈ [A, B] can have

learnable parameters.

Grigorios Chrysos An introduction to Normalizing Flows January 19, 2021 20 / 26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/main-210623062100/85/An-introduction-on-normalizing-flows-25-320.jpg)