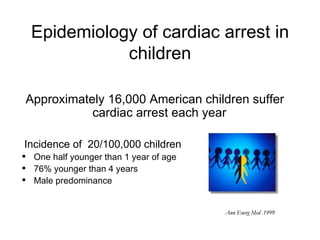

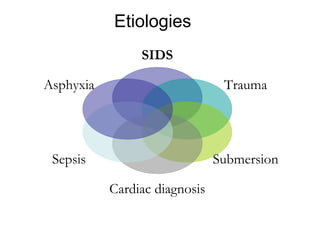

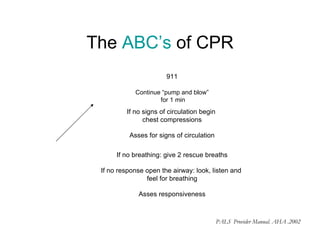

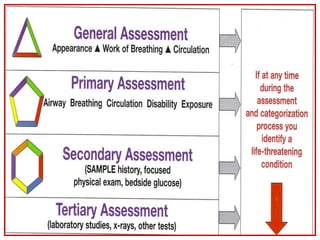

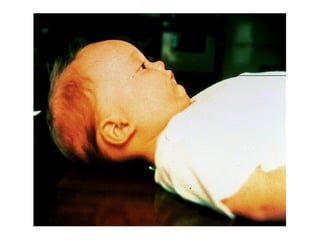

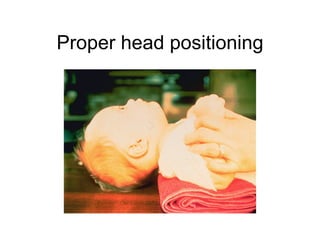

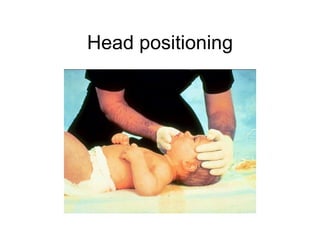

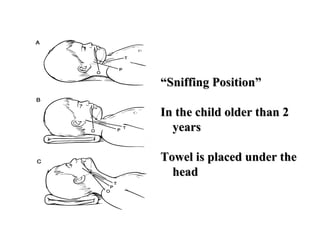

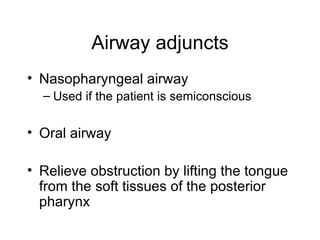

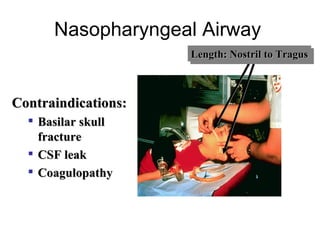

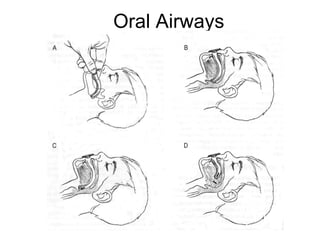

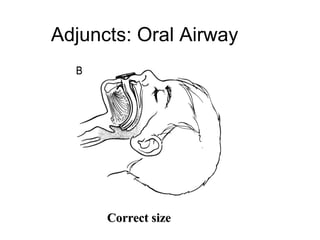

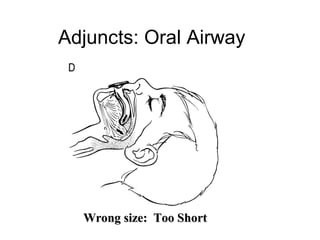

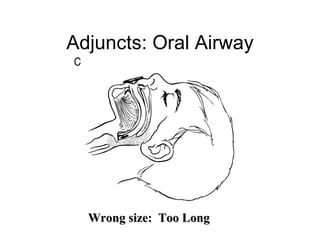

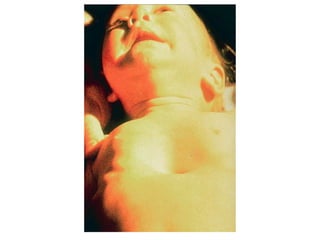

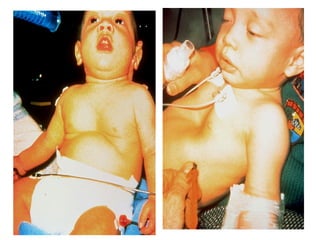

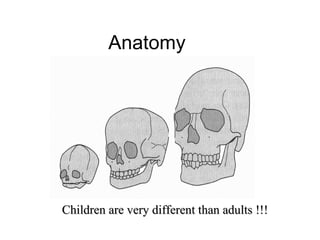

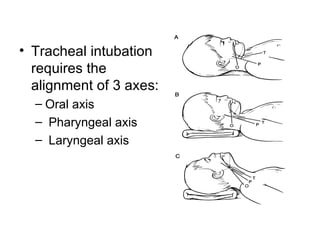

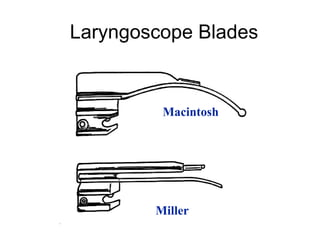

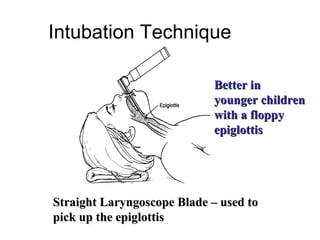

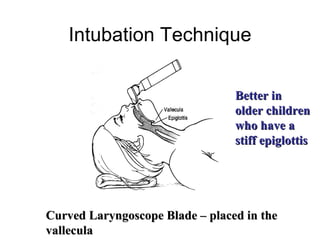

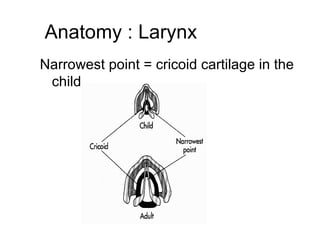

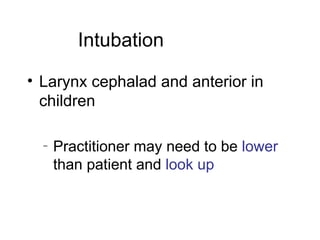

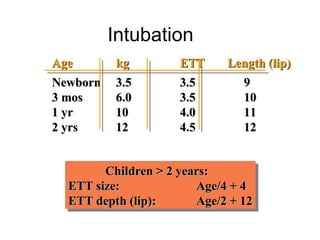

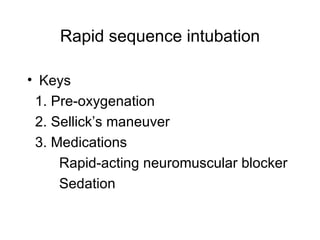

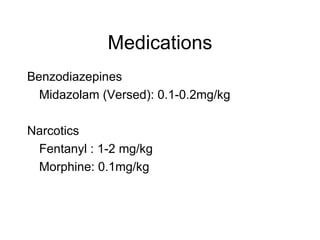

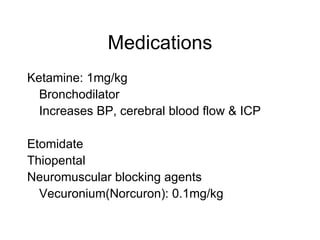

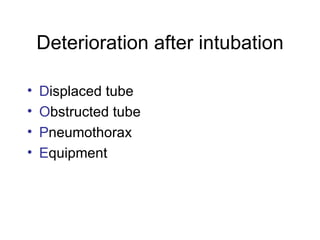

The document discusses pediatric airway management and cardiac arrest in children. It notes that approximately 16,000 American children suffer cardiac arrest each year, with half being younger than 1 year old. Most pediatric "codes" are of respiratory origin. Proper positioning of the head and use of airway adjuncts like nasopharyngeal and oral airways can help relieve airway obstruction. Tracheal intubation is indicated for respiratory failure, shock, or inability to protect the airway. Rapid sequence intubation is recommended for critically ill children to prevent aspiration, using pre-oxygenation, cricoid pressure, and sedative medications. Anatomy, appropriate tube size, and intubation technique differ significantly in children