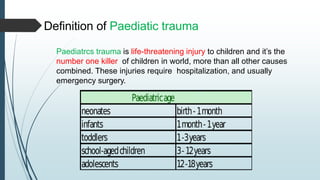

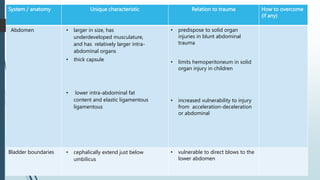

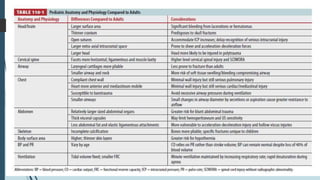

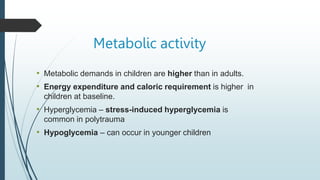

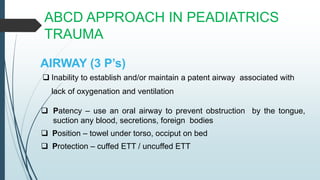

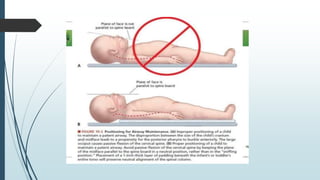

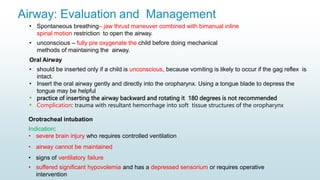

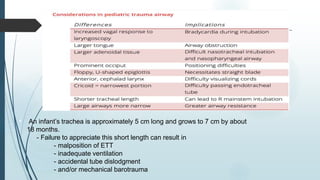

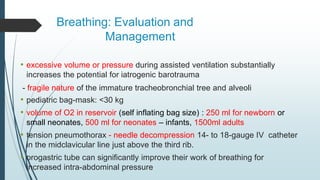

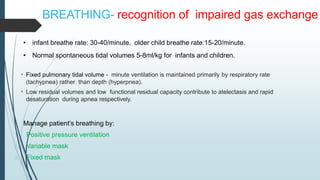

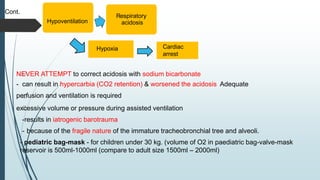

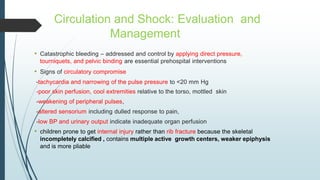

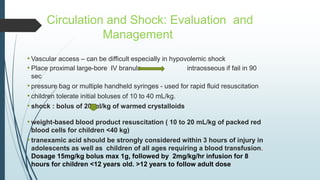

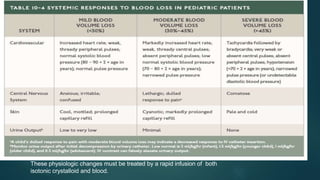

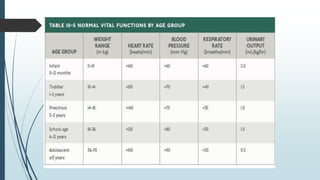

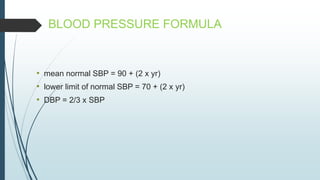

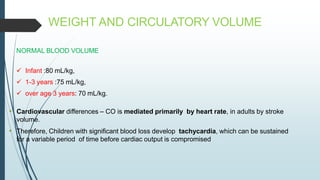

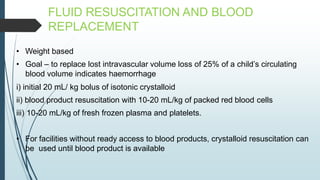

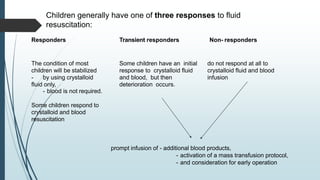

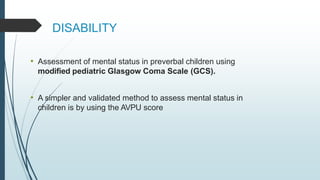

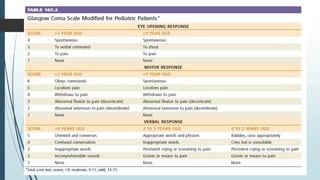

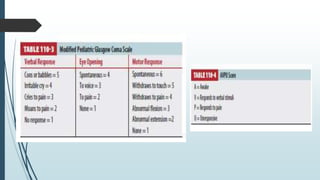

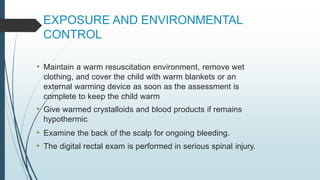

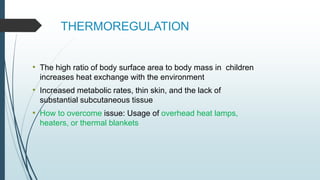

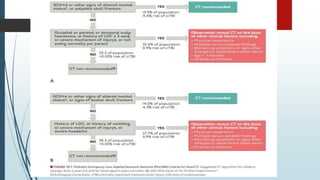

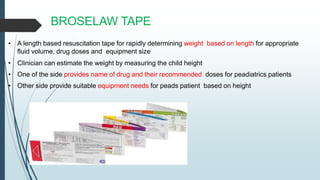

Paediatric trauma patients have unique anatomical and physiological characteristics compared to adults. These include a larger head size, more flexible bones, higher metabolic rate and greater risk of hypothermia. The ABCD approach is used to assess and manage the airway, breathing, circulation and disability of paediatric trauma patients. Special considerations include low tidal volumes during ventilation, weight-based fluid resuscitation, and assessing mental status using the Glasgow Coma Scale or AVPU score. Maintaining normothermia through warming measures is also important due to their increased risk of heat loss. Head injuries require rapid evaluation and treatment to prevent secondary brain injury.