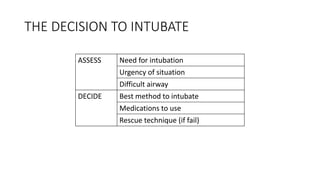

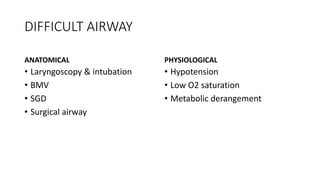

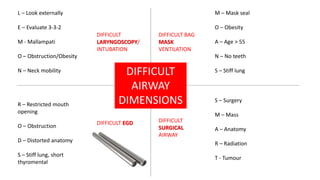

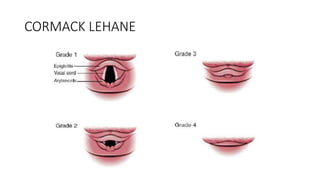

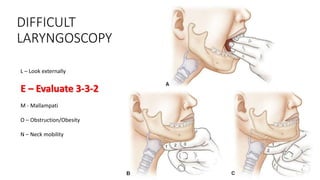

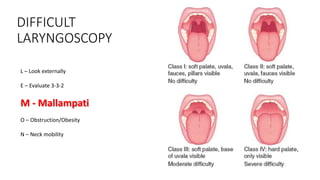

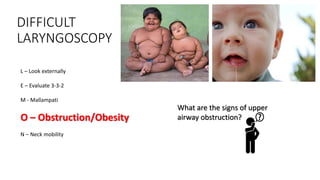

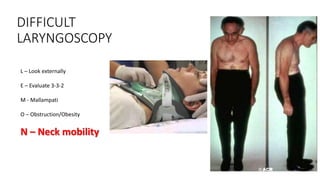

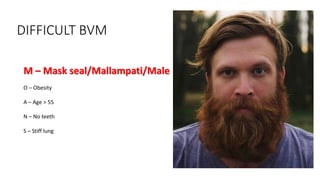

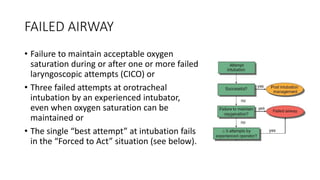

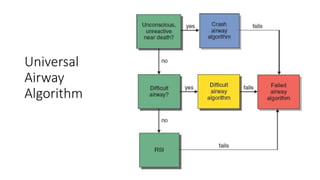

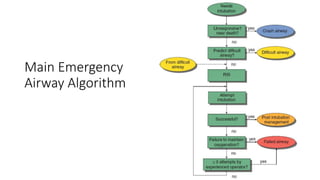

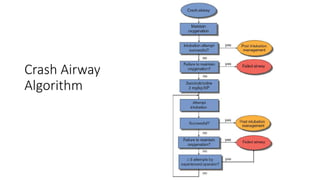

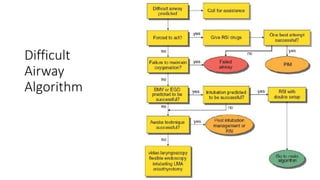

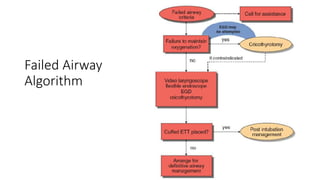

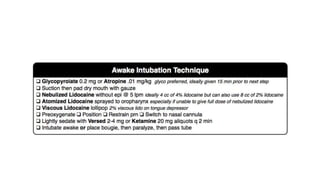

This document outlines airway management algorithms for intubation in the emergency department, with a focus on difficult airway situations. It describes the decision-making process for intubation, including assessing the need for intubation and choosing the best intubation method and rescue techniques. Factors that can make airways difficult are discussed, such as anatomical and physiological challenges. Specific algorithms are presented for managing difficult laryngoscopy, difficult bag mask ventilation, and failed airway scenarios. Assessment tools for predicting difficult airways, like the LEMON and RODS scoring systems, are also covered.