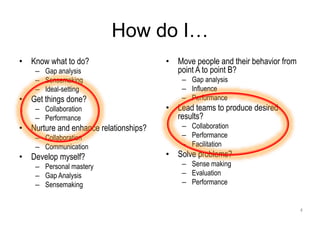

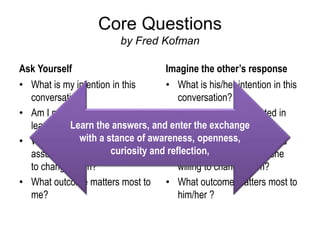

This document discusses balancing advocacy and inquiry when communicating with others. It provides guidelines for expressing one's own perspective while also seeking to understand other perspectives. The key points are:

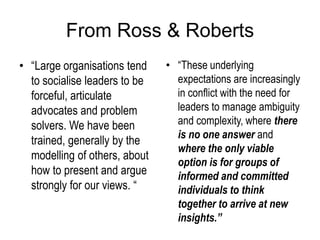

1) Advocacy and inquiry both have value, but should be balanced - one should lay out their own reasoning while also encouraging challenges from others and exploring other views.

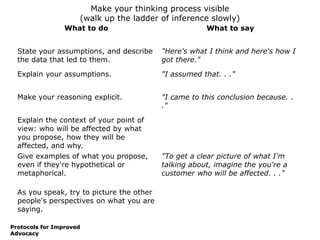

2) Making one's thinking process visible helps others understand one's perspective, for example by explaining assumptions and how conclusions were reached.

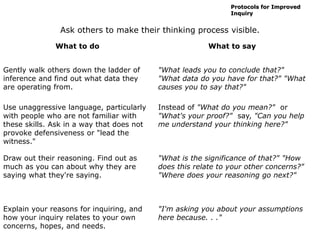

3) Inquiring about others' reasoning and assumptions in a non-confrontational way can help uncover new insights, as can comparing different perspectives on an issue.

4) When disagreements arise, focus on exploring the