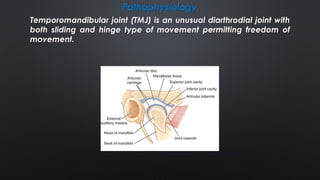

This document provides information on temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation, including types, causes, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Some key points:

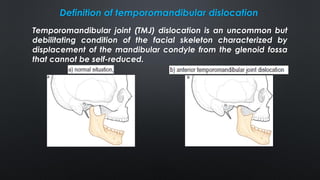

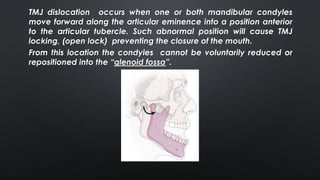

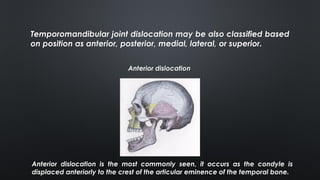

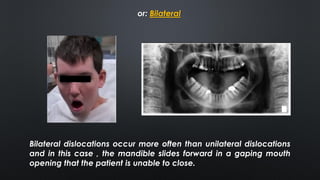

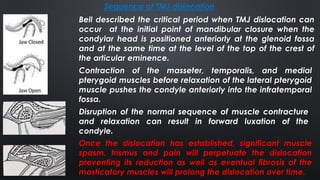

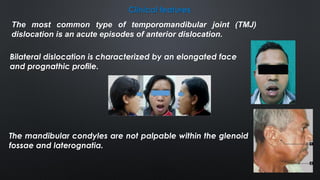

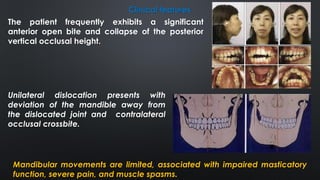

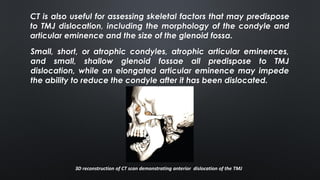

- TMJ dislocation occurs when the mandibular condyle moves out of position in the glenoid fossa, preventing mouth closure. It can be acute or chronic.

- Acute dislocations are usually anterior and cause inability to close the mouth, pain, and muscle spasms. Chronic dislocations involve fibrosis and joint degeneration.

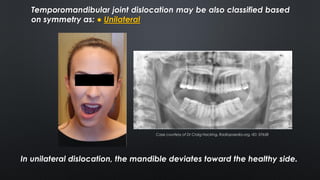

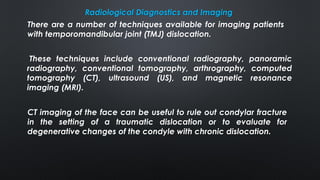

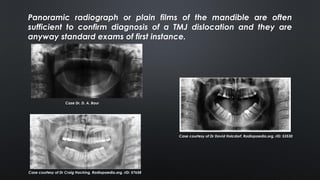

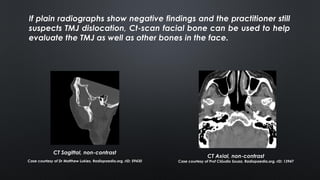

- Diagnosis is based on clinical exam showing inability to close the mouth and deviation of the chin. Imaging like panoramic x-rays or CT can confirm displacement of