This document discusses the globalization of Chinese enterprises. Some key points:

- Globalization has become necessary for Chinese enterprises as China integrates further into the global economy and a multi-polar world emerges with new opportunities for emerging market multinationals.

- For Chinese companies to develop further, they must globalize their operations beyond China's borders. This involves gradually becoming more reliant on overseas markets and improving global operations management.

- Few Chinese enterprises have reached an advanced stage of truly global operations unbound by national borders. Most are in the initial or intermediate stages of some global market interaction or optimizing their value chains for exports. However, since the 2008 financial crisis, Chinese firms have accelerated their globalization

![24

Chinese companies seeking to globalize

face numerous strategic questions—

including why the company should go

global, what businesses it should engage

in, where it should locate its global

activities and operations, and what

means of investment the company will

use to conduct business globally. The

goals of globalization and the industries

in which companies compete will

influence the answers that executives

generate for these strategic questions.

1. Why should our

company go global?

Globalization has now become an

inevitable trend for Chinese enterprises.

In the post-crisis era, in particular,

globalization enables Chinese companies

to achieve performance breakthroughs

and fuel long-term development. A

globalized firm has access to more

resources, wider markets, more

diversified talent and a more innovative

environment. However, Chinese

businesses have gone global for a set

of distinctive strategic reasons and

motivations. The “breakthroughs” they

seek by way of globalization therefore

have multiple meanings – breaking

threats to their survival, breaking

limitations to development, breaking

their reliance on certain growth paths

and breaking their traditional status

as followers rather than leaders. Our

observation reveals four different

motivations behind Chinese companies’

push for globalization.

Reduce threats to survival

The global financial crisis presented

Chinese enterprises with immense

challenges; some businesses’ very

survival was threatened. Export

processing enterprises, represented

by the traditional OEM manufacturers

of apparel and toys in the Pearl River

Delta, have borne the brunt of the

crisis, owing to their lack of adequate

domestic sales and marketing systems,

insufficient capabilities for innovation

and reliance on foreign orders. As many

countries raised trade barriers during the

recession, numerous Chinese exporters

faced a shrinking international market

and the specter of bankruptcy. At the

same time, countries including India

and Vietnam increasingly became the

destination of choice for multinational

corporations seeking cheap labor, a

trend that has eroded China’s labor-

cost advantage. Under these worrisome

circumstances, many export-oriented

businesses have decided to go beyond

China’s national border and capture host

countries’ markets by establishing local

production and distribution channels

or leveraging those countries’ low-cost

advantage. For example, one Chinese

company runs an industrial park in a

Southeast Asian country jointly with a

local partner. The executives from the

company revealed that the majority of

investors setting up businesses in the

park were Chinese enterprises. Some

Chinese businesses quickly signed leasing

contracts because their exports from

China to the European and US markets

faced anti-dumping investigations. They

had to relocate their businesses quickly

to a third country to avoid disruption to

exports.29

Expand space for development

Although the global economy remains

sluggish, China has a vast number of

ambitious and pioneering enterprises

that are experiencing a growth spurt or

have remained stable and strong. The

global devaluation of assets in the post-

crisis era has created a rare opportunity

for these companies to expand their

overseas markets and leverage those

markets’ resources. At the same time,

other Chinese enterprises are following

suit because of saturation of the

domestic market, vicious competition

or dearth of critical resources. For

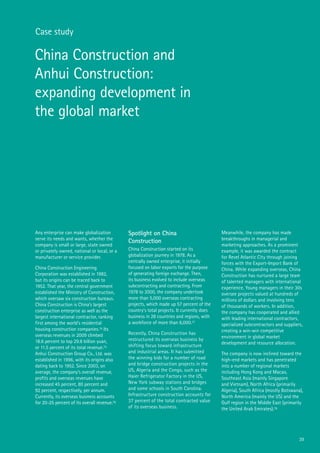

instance, competition within China’s

construction industry has intensified,

especially with the entry of foreign

construction contractors. In the face of

shrinking profitability, many construction

companies, such as the China

Construction Engineering Corporation

and the Anhui Construction Group, have

chosen to go global. Ambitious and

strong firms have decided to globalize

to escape the constraints of the home

market and maximize their development

on the global stage.

Move up the value chain

Moving up the value chain can help

Chinese businesses improve their

profitability and achieve sustainable

development. But deficiency in

capabilities in business functions such

as financing, research and development,

production, branding and marketing

has limited these companies’ ability to

move up the value chain. Globalization

provides the necessary conditions for

Chinese enterprises to optimize their

operations and extend their value chain.

The Chery Company, for instance, has

promoted its products in the EU and

North American markets while meeting

the domestic need for low-end cars.

(See “Case study: A tale of two Chinese

automakers..”) The Haier Group, on

the other hand, pursues globalization

through the “resource for resource”

approach, thereby extending its value

chain from its main line of products to

high-end products.

Become a global player

Since China’s movement toward reform

and opening up, foreign investments

have flowed into the country and have

brought advanced technologies and

managerial expertise. Most Chinese

enterprises were passive recipients of

these new experiences at first. Some

gradually became active followers

of best practices. As China is more

and more integrated into the world

economy, Chinese companies are no

longer content to follow and compete

in the domestic market. Going global is

the right choice for Chinese enterprises

seeking to develop and excel today.

Since the launch of the “going out”

strategy in the mid-1990s, the Chinese

government has consistently supported

enterprises of various ownership

structures in their efforts to engage

in international economic activity

and technological cooperation and to

build global brand names. The global

financial crisis in 2008 created the

opportunity for Chinese enterprises to

“go out” further. Blessed with favorable

conditions, a large number of visionary

companies are pursuing globalization

in an effort to become multinational

companies with international brand

names. The Chery Company, in expanding

to overseas markets, will focus on the

long-term objective of constructing an

international brand name. The Wanxiang

Group has also established its “going

“For CSR, [competing] in the global market today means

[our] survival and development tomorrow.”

Zhao Xiaogang, Chairman, CSR Corporation Ltd.30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/477cc4f2-123b-4e09-ab8c-f59f0749d907-151218045650/85/Accenture-Globalization-Report-2010-24-320.jpg)

![49

Figure 25 Performance management promoting globalization

Value chain

optimization linked

to performance

management

Driving individual

and organizational

performance to

facilitate globalization

Source: Accenture

Globalization

Strategy and

competitiveness

Optimization of

the value chain

Organizational matrix

Execution

Balanced scorecard

Business unite performance metrics

Individuals performance metrics

“Whether an enterprise is truly global does not depend

on how [many] assets it has acquired overseas.

Instead, one should examine if the company possesses

global brands, global operating capabilities, and if its

management philosophy, organizational structure,

human resources and corporate culture are all

globalized.”95

Liu Jiren, President of Neusoft

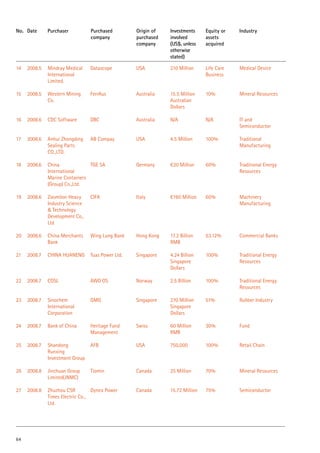

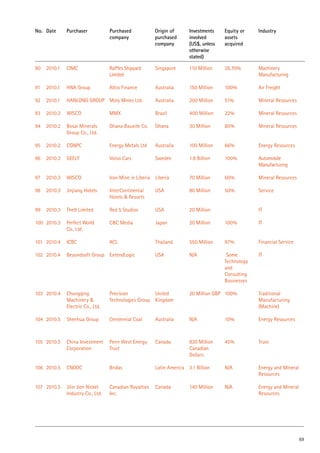

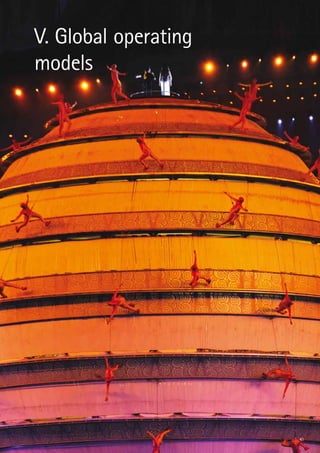

1.5 Performance metrics

Effective performance metrics

ensure successful management of

an enterprise’s global business. A

performance evaluation system should

be directly linked to the globalization

process and therefore facilitate

coordination of various global business

priorities. When a company establishes

the right performance metrics, internal

and external activities work in concert

and thus support the development of

new products or services. According

to Accenture research, to achieve high

performance, a globalizing enterprise

should set clear strategic goals and a

roadmap, establish an organizational

structure and business processes on that

basis and define a detailed execution

plan to promote its globalization process.

Metrics assess, incentivize and manage

the performance of the organization

overall as well as employees and

thus improve the enterprise’s value-

creation process. Effective performance

management links the organization’s

strategic priorities and execution

plans to different levels within the

organization, from the top management

team down to individual employees.

By linking business requirements to

organizations and individuals, the right

metrics drive performance, thereby

accelerating globalization (See Figure 25).

The establishment of key performance

indicators is crucial for the

implementation of a performance

management system. A company’s

senior management team should define

financial and nonfinancial indicators for

assessing business processes, employee

quality and leadership skills. Many

multinational corporations adopt the

balanced scorecard methodology for

performance management. The balanced

scorecard enables every individual in the

organization to understand how his or

her performance and decisions influence

the entire organization. Through this

approach, the organization can define

measurable goals, gain companywide

consensus on their importance and

establish accountability for achieving

the goals.

The top management team should

consider how to evaluate performance

of different business units across various

regions, because performance evaluation

influences employees’ work priorities

and orientation. Evaluation criteria

usually include profitability, costs and

other areas (such as global market share,

speed of new product launches on the

global market and the number and

profitability of new products). Evaluation

criteria should communicate clearly

defined priorities; be based on particular

organizations’ key roles, responsibilities

and goals; be consistent across

departments; and aim to strengthen

the entire organization’s competitive

position.

As Chinese enterprises have continued

down the path of globalization, they

have realized that a performance

evaluation system plays an indispensible

role in improving management of their

global business. This is particularly the

case for companies involved in overseas

M&As. Management of the merged or

acquired company through strategic

planning, goal setting and performance

appraisals has proven effective for

addressing challenges that arise during

the post-merger integration process (See

“Case study: Lenovo: a new chapter in

global operation”).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/477cc4f2-123b-4e09-ab8c-f59f0749d907-151218045650/85/Accenture-Globalization-Report-2010-49-320.jpg)