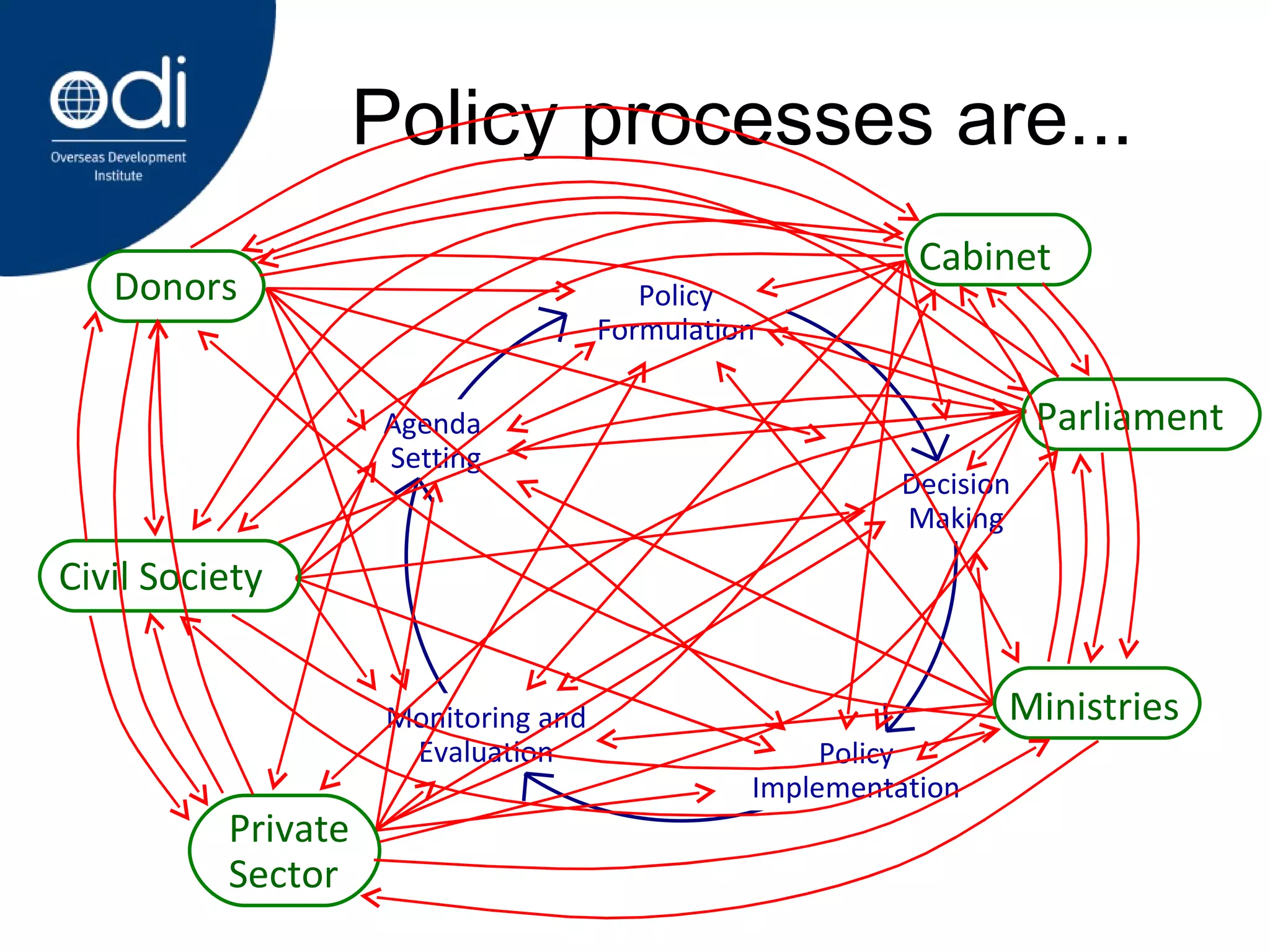

The document outlines the agenda and activities of a policy engagement tutorial held in Dakar, Senegal. It includes:

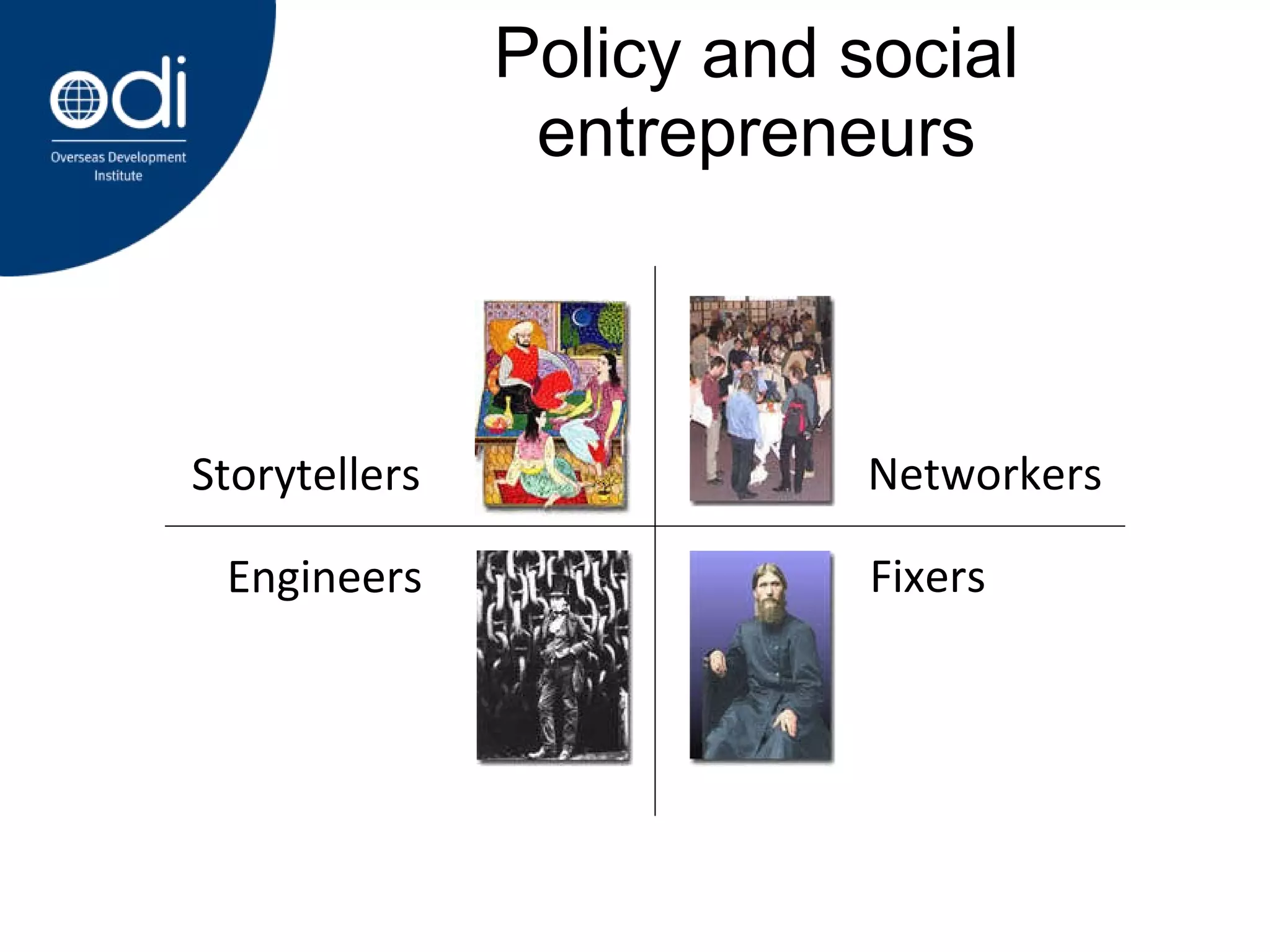

- Storytelling exercises where participants shared experiences engaging with policy processes

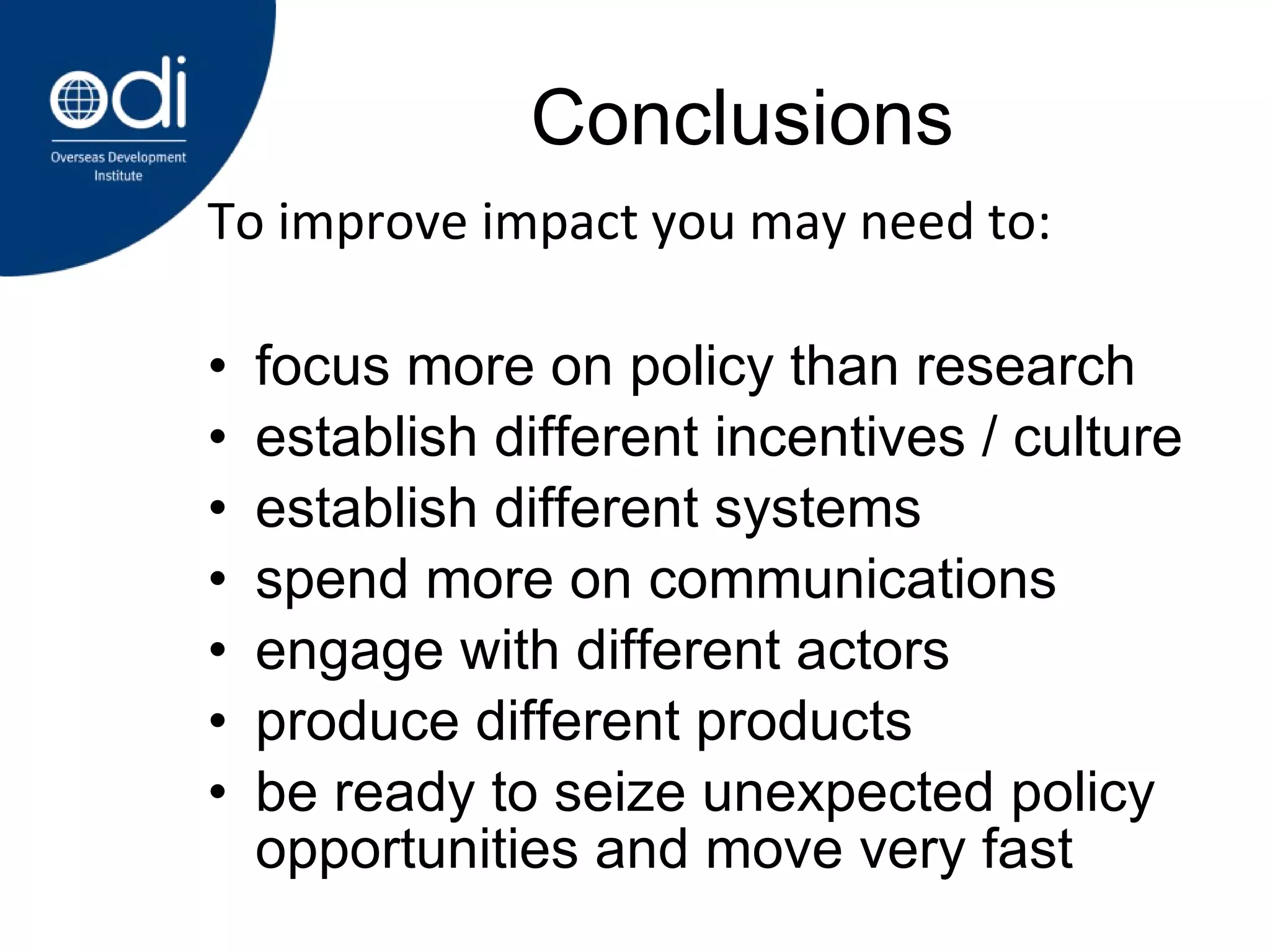

- Identification of 6 key lessons for effective policy engagement based on collective experiences

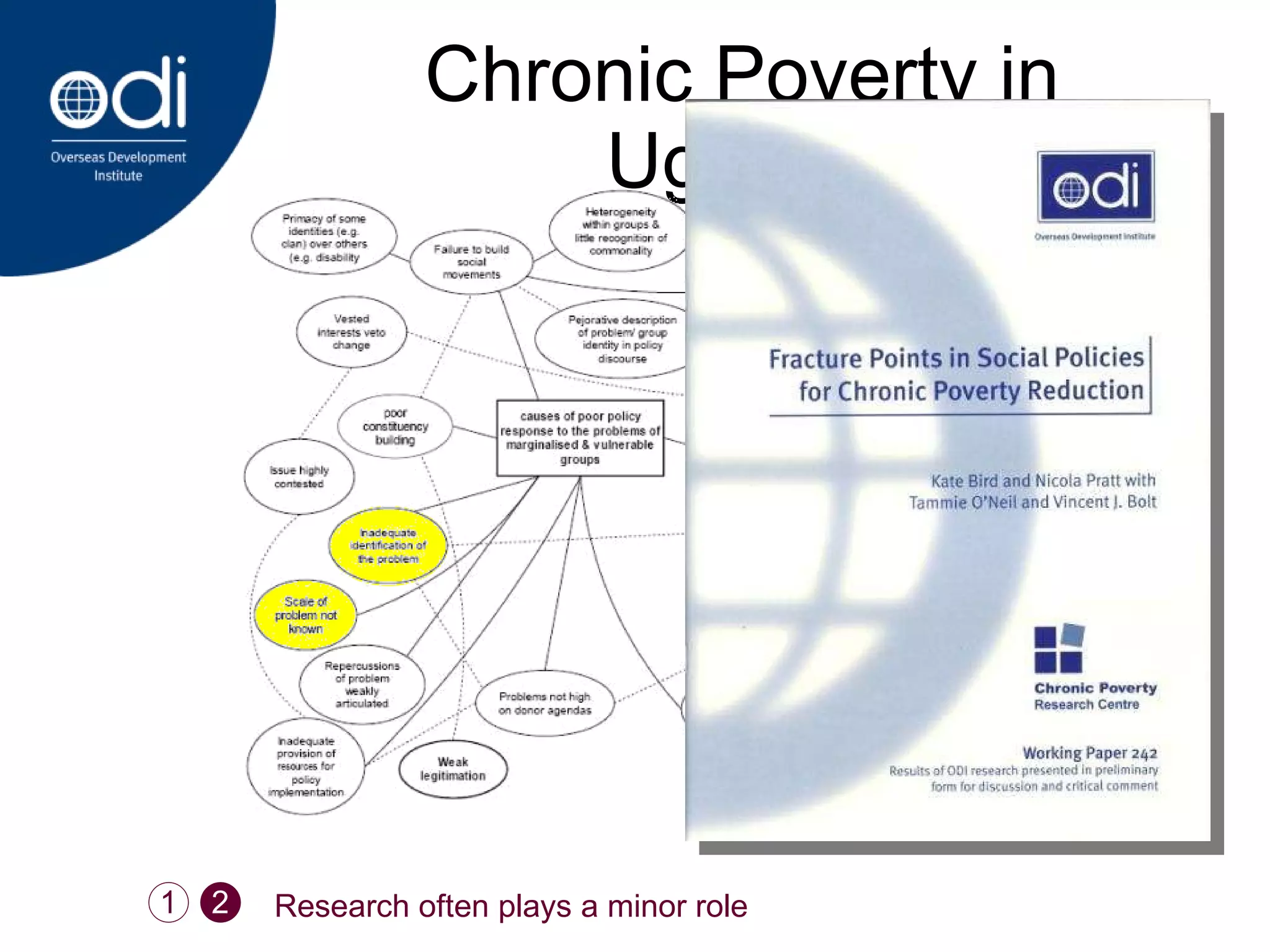

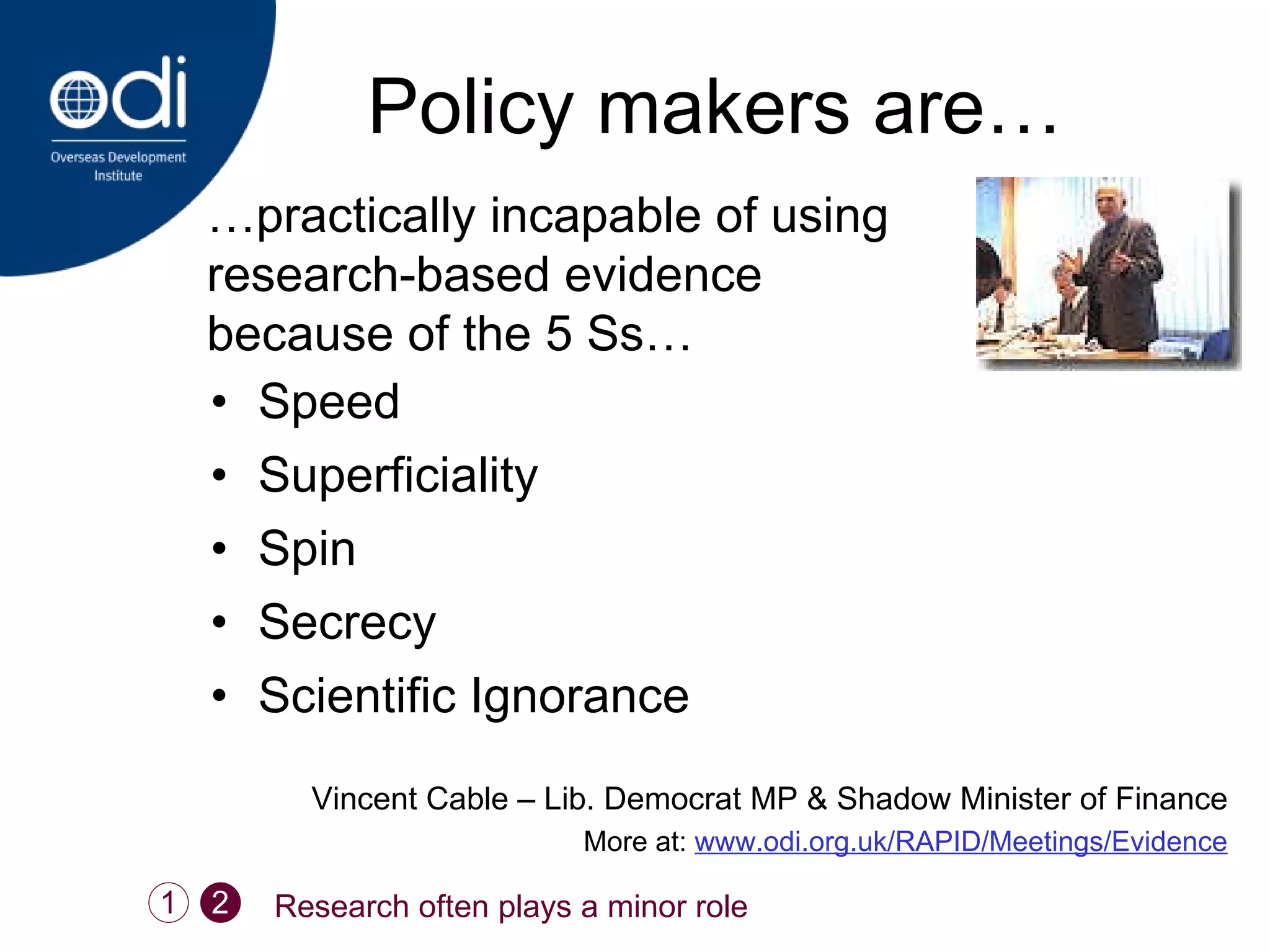

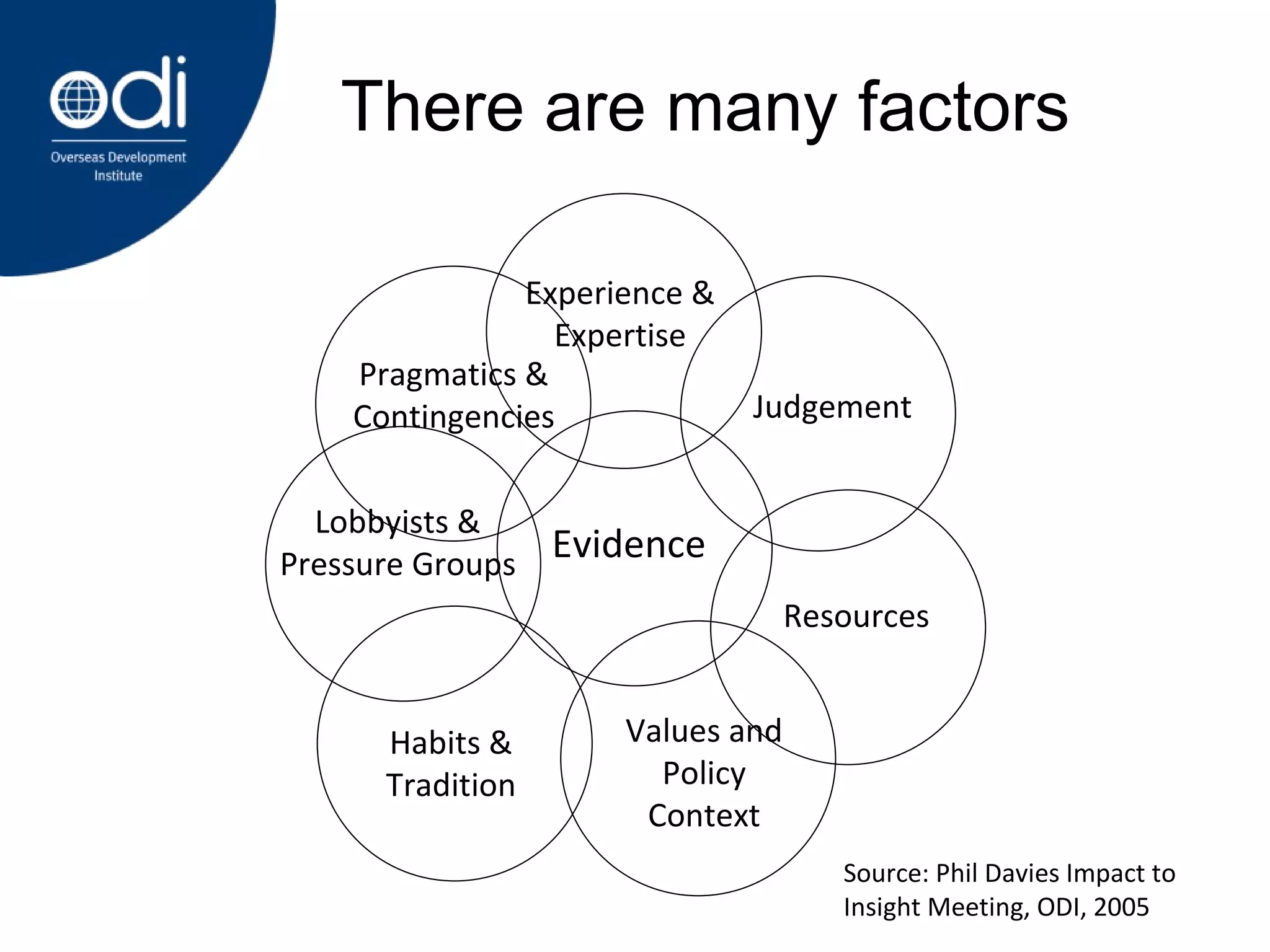

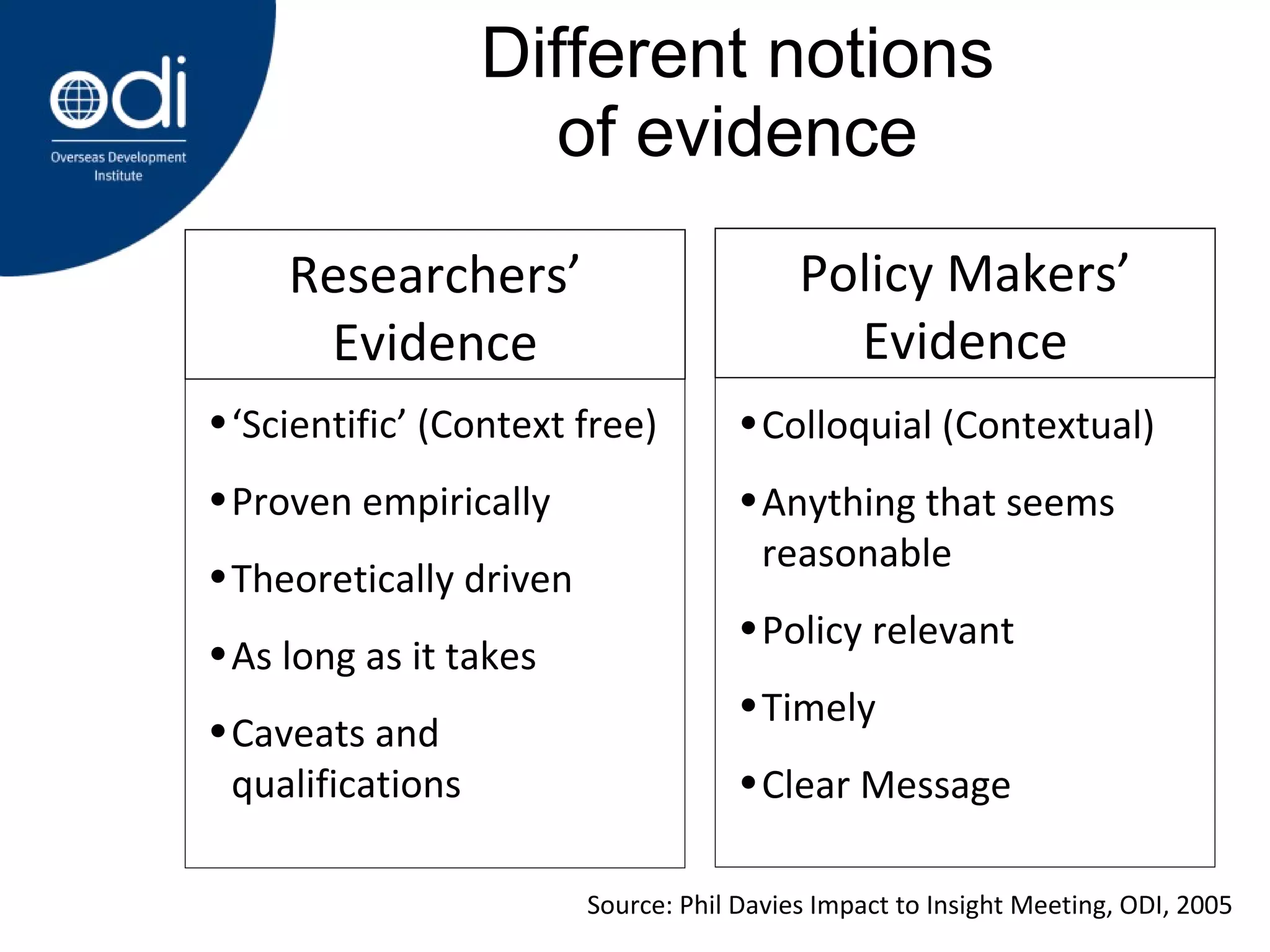

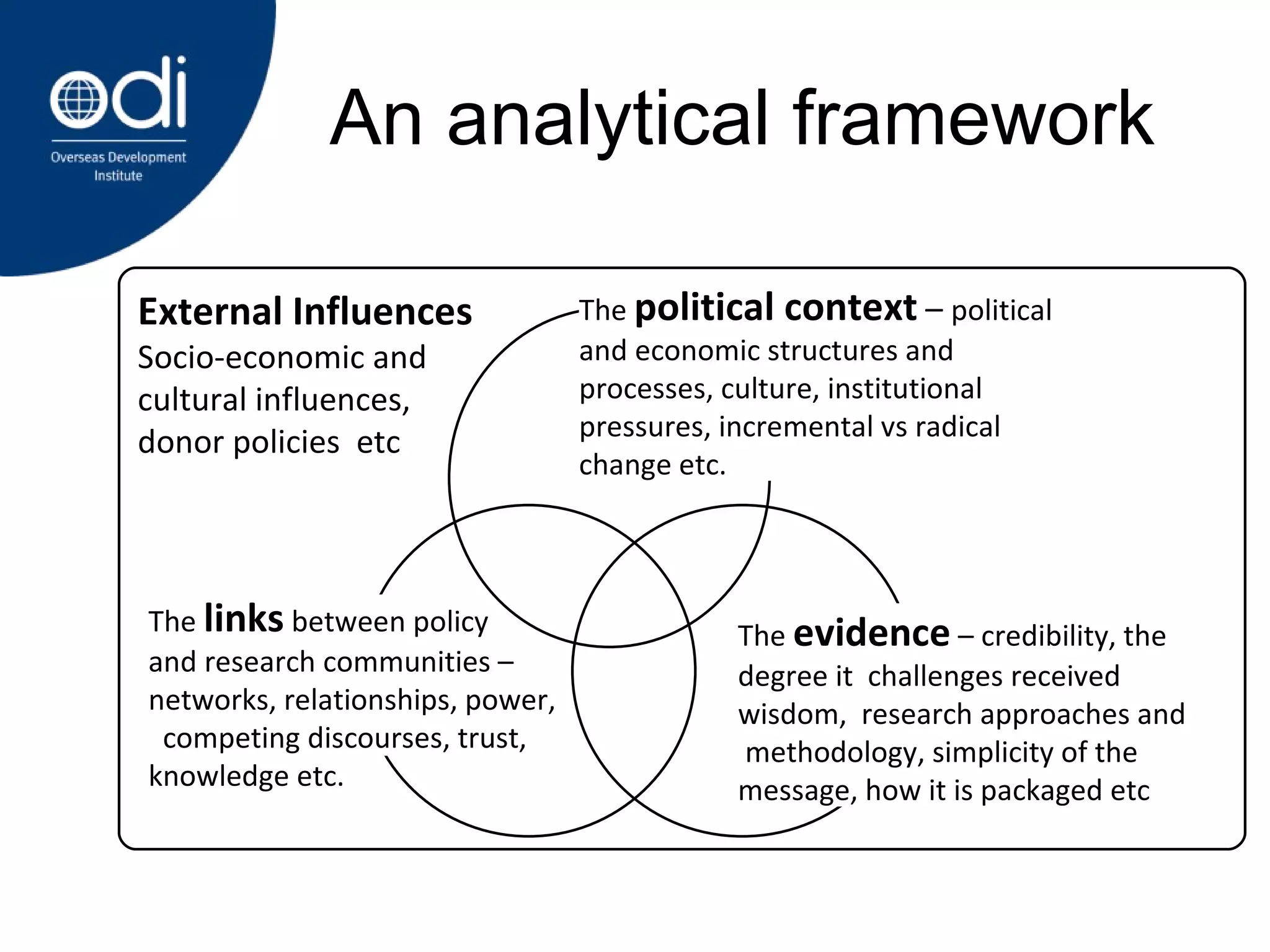

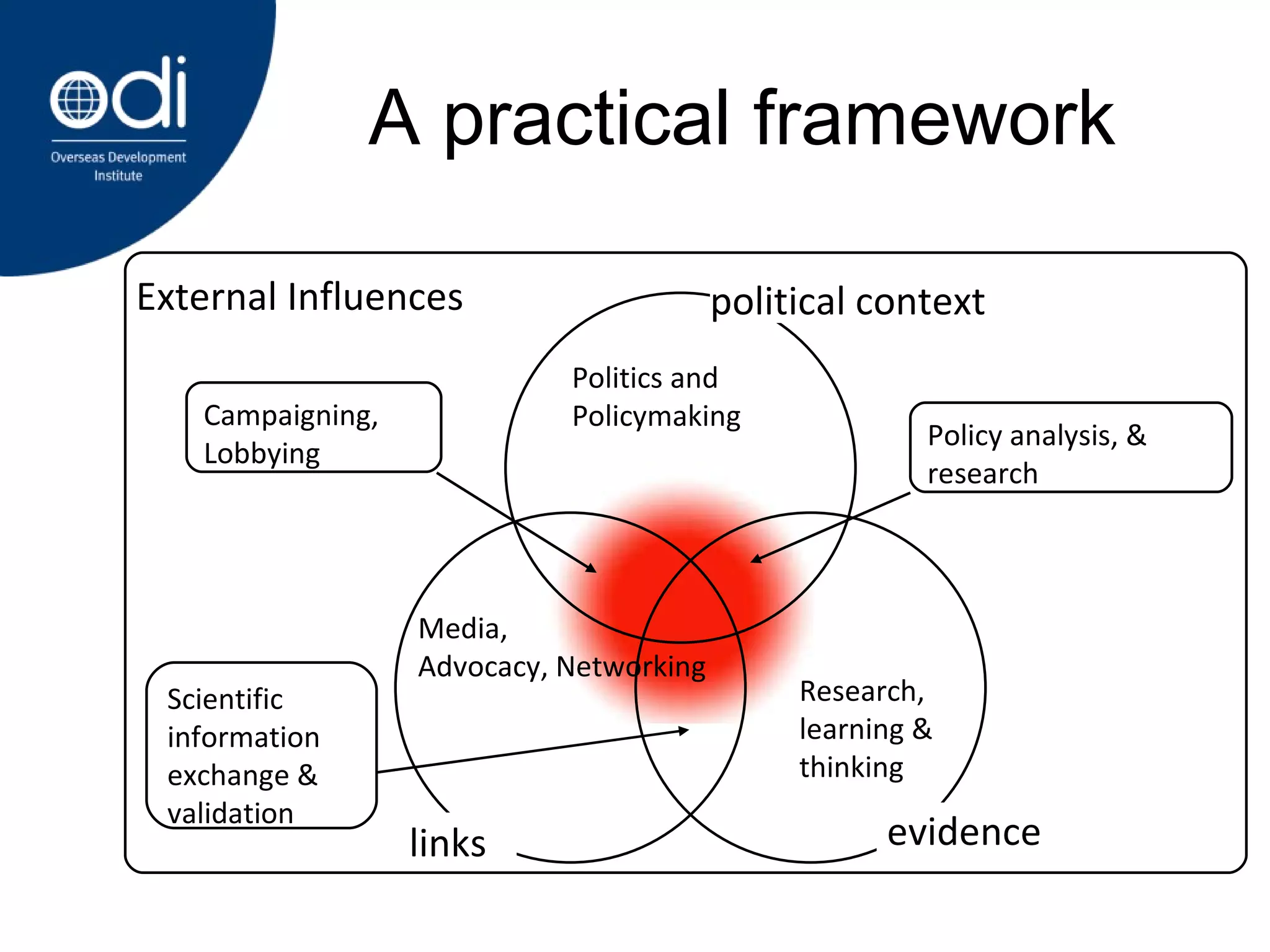

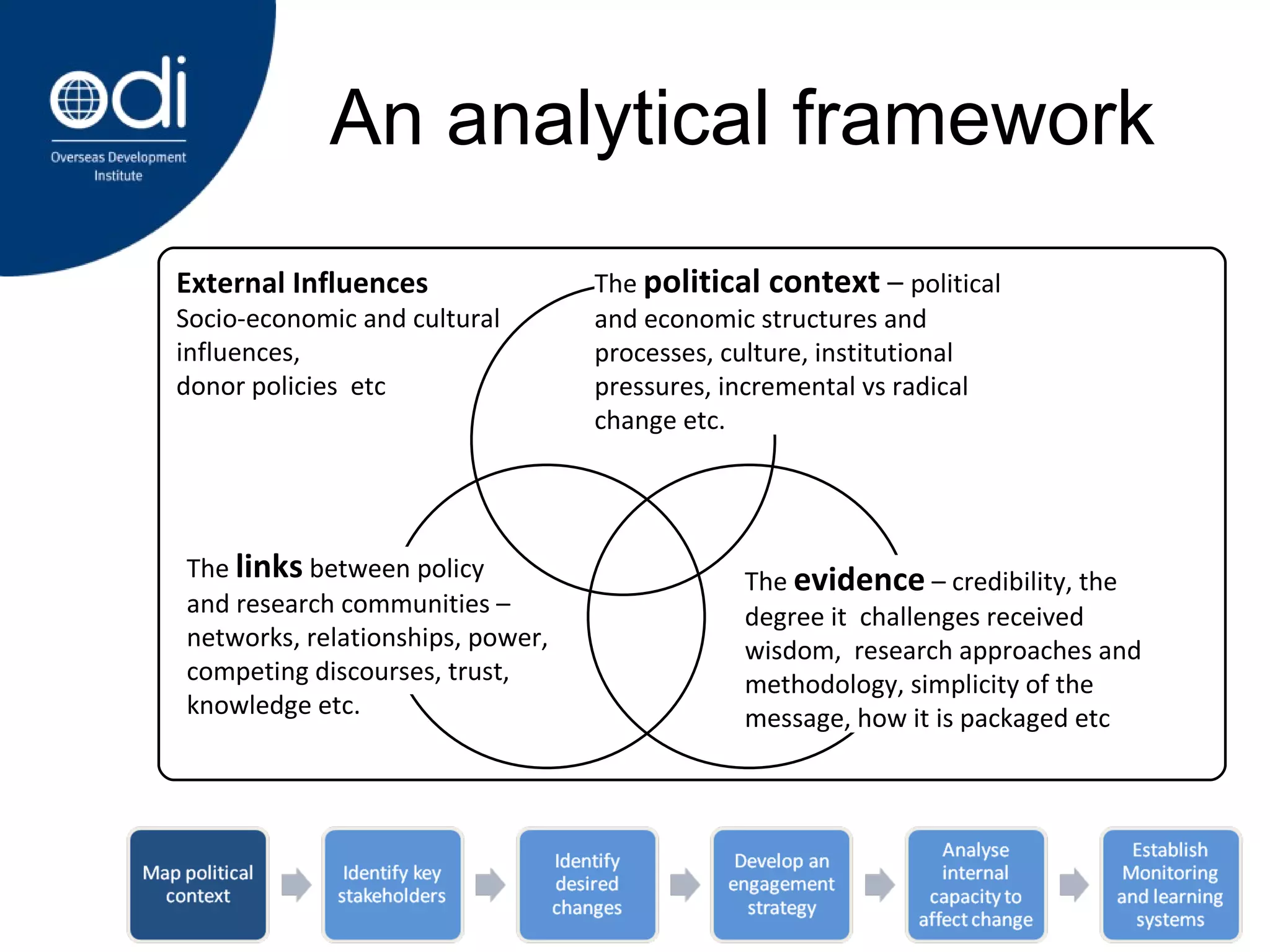

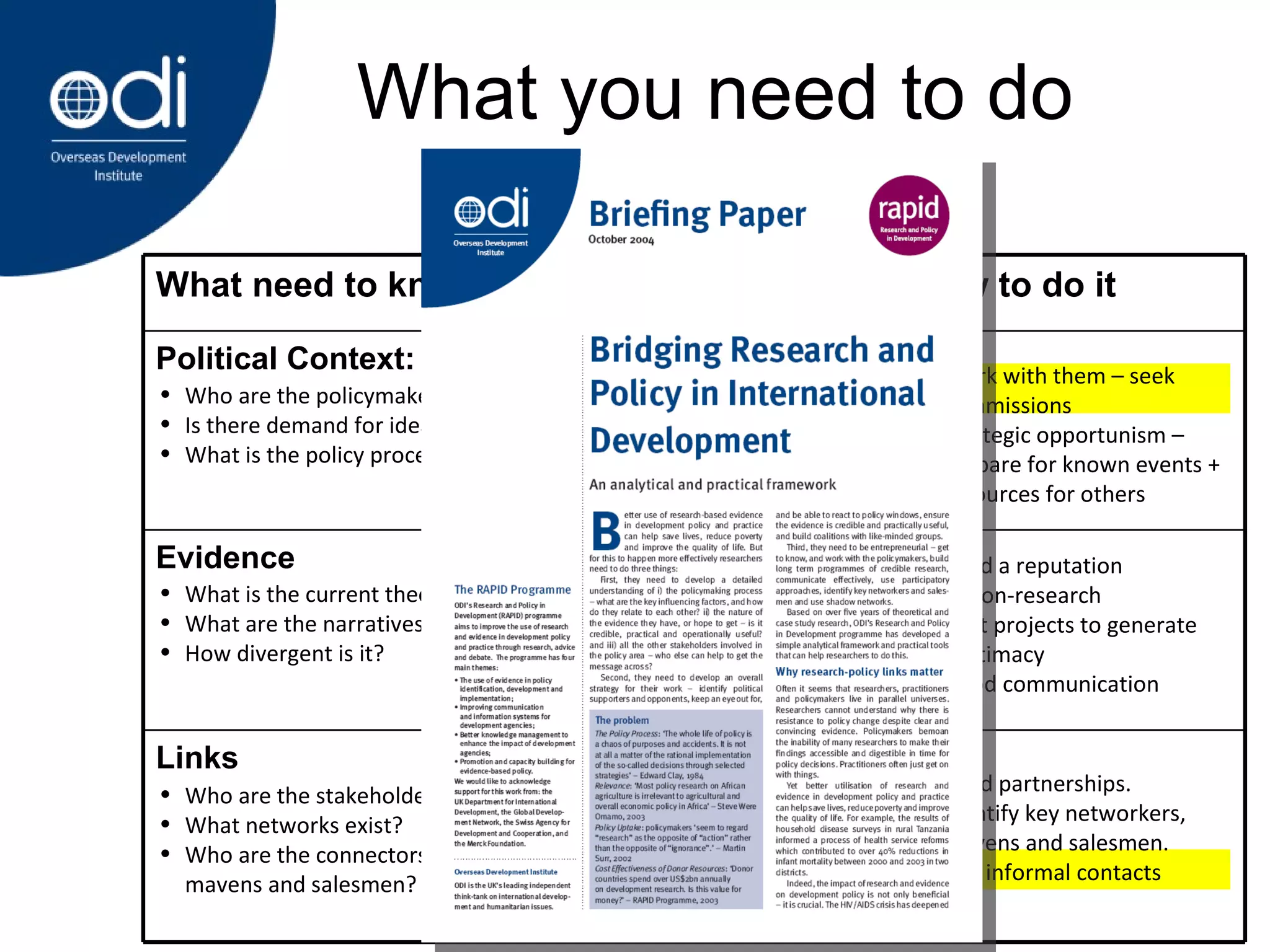

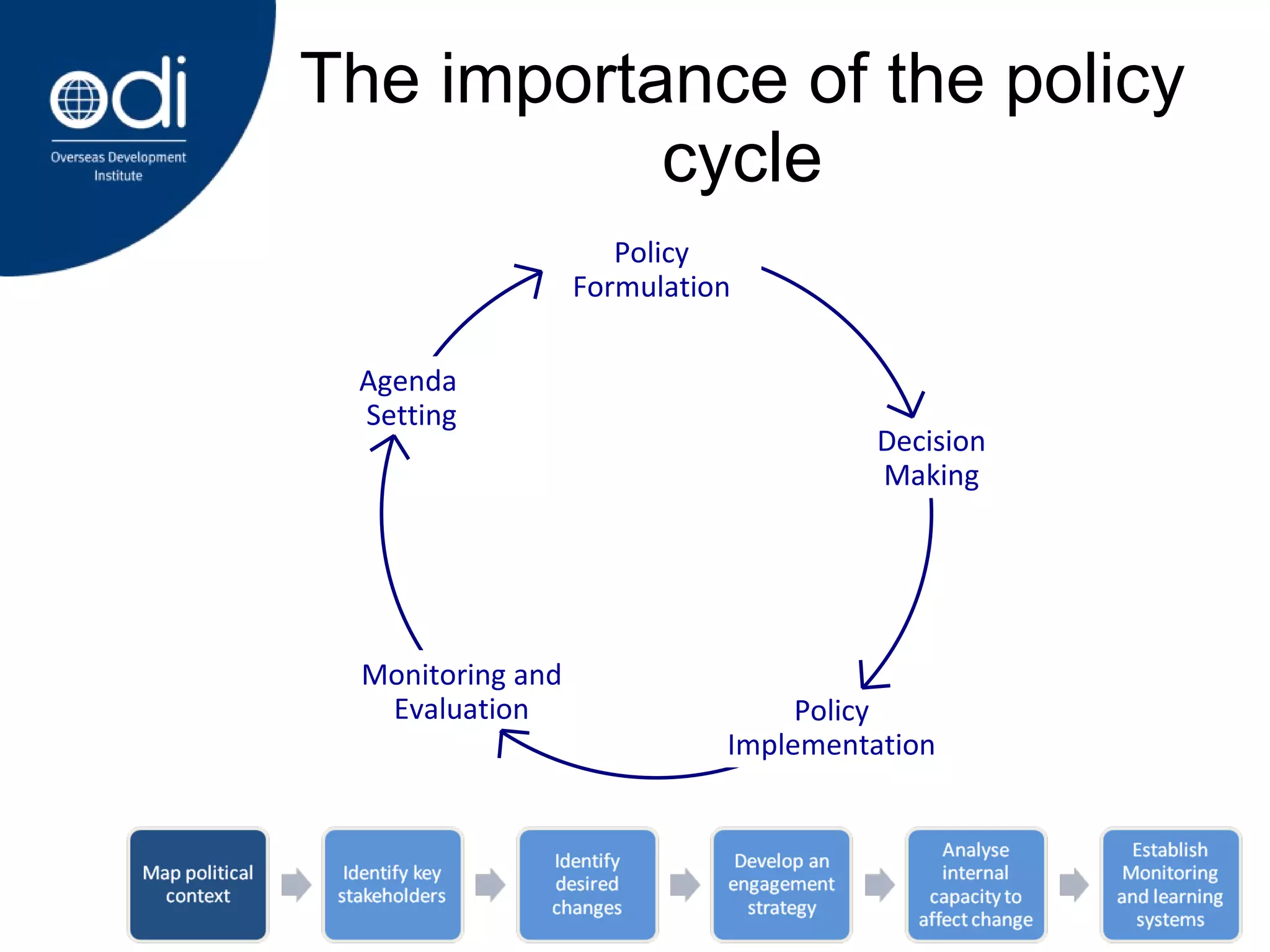

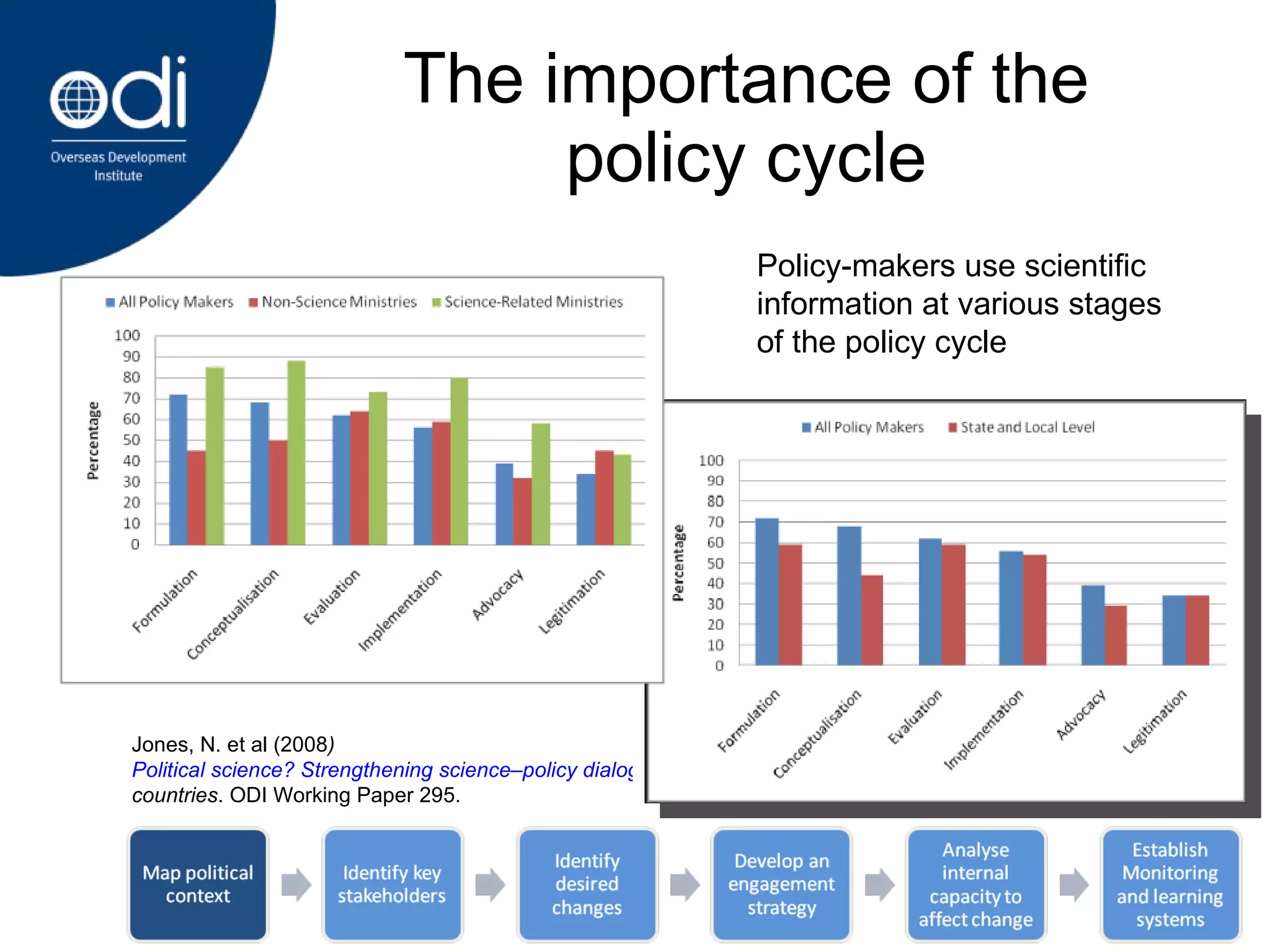

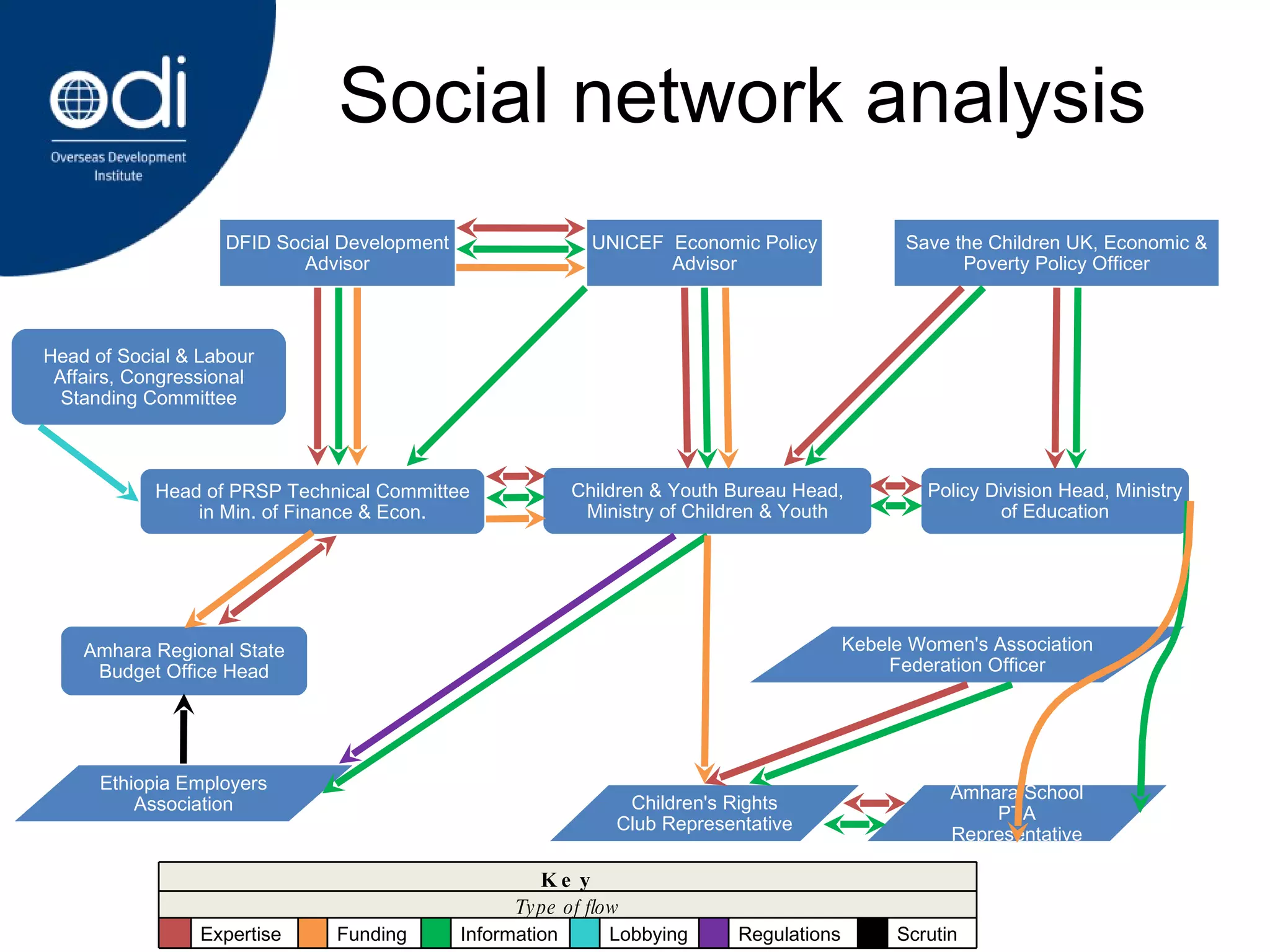

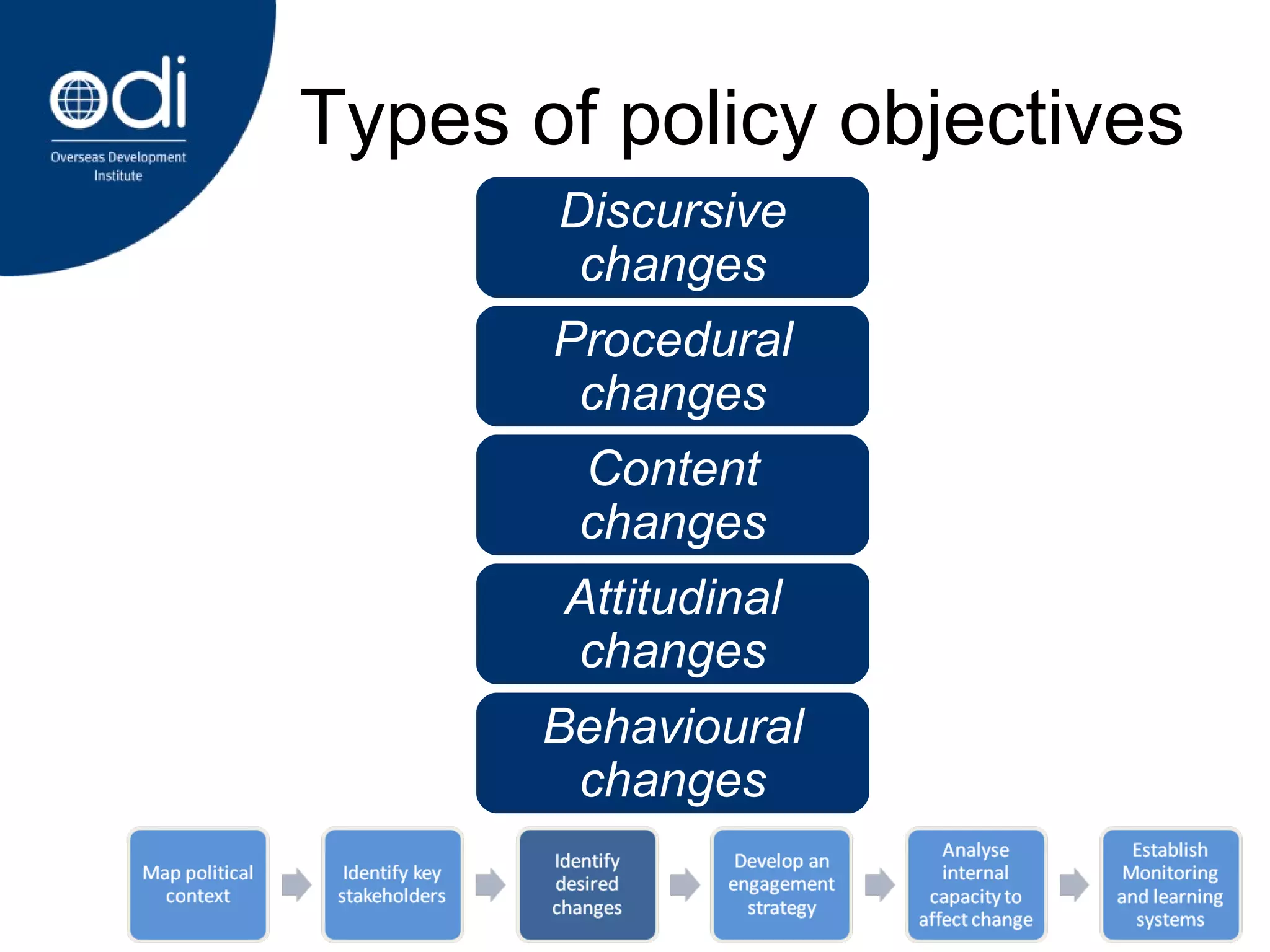

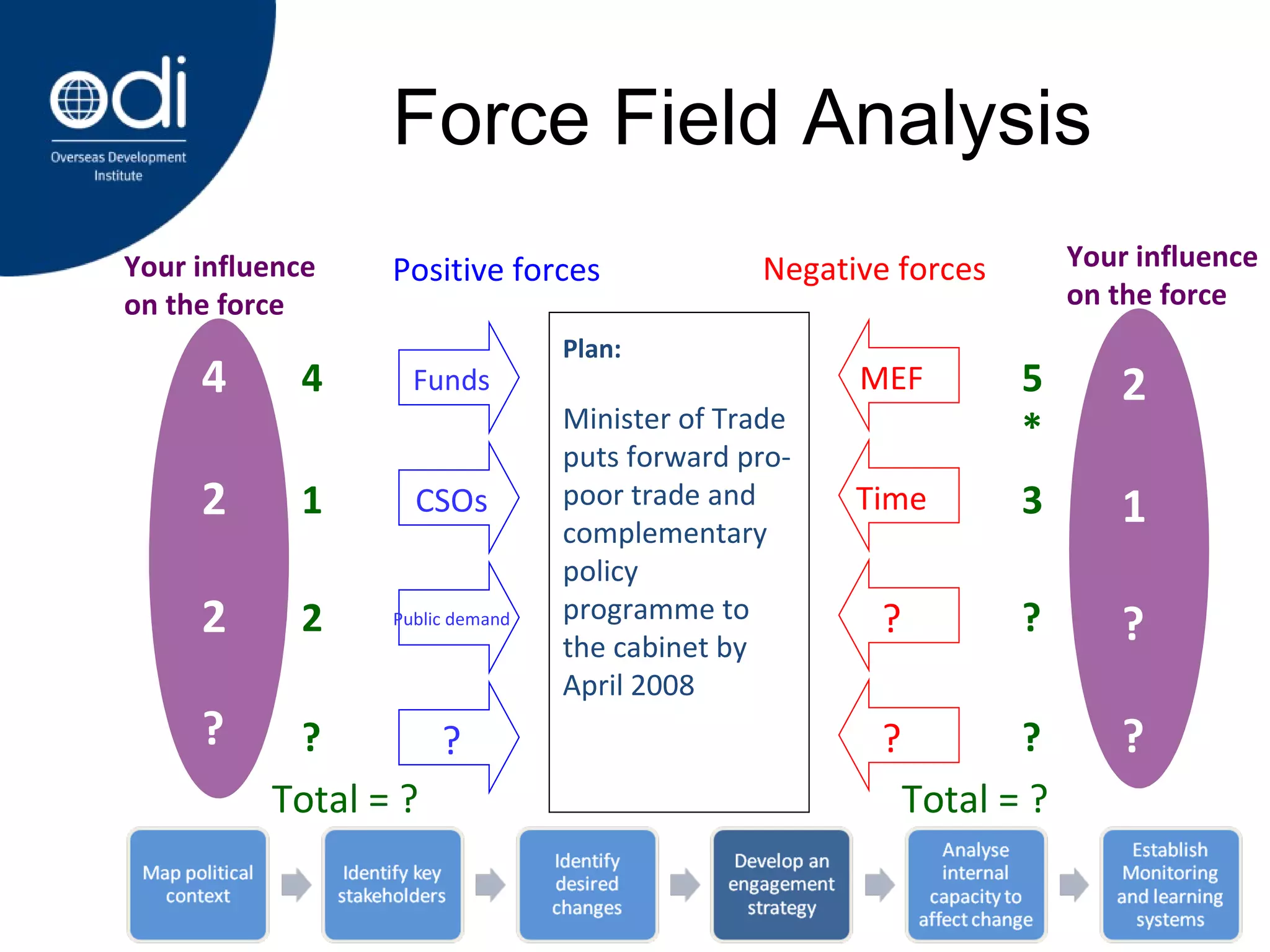

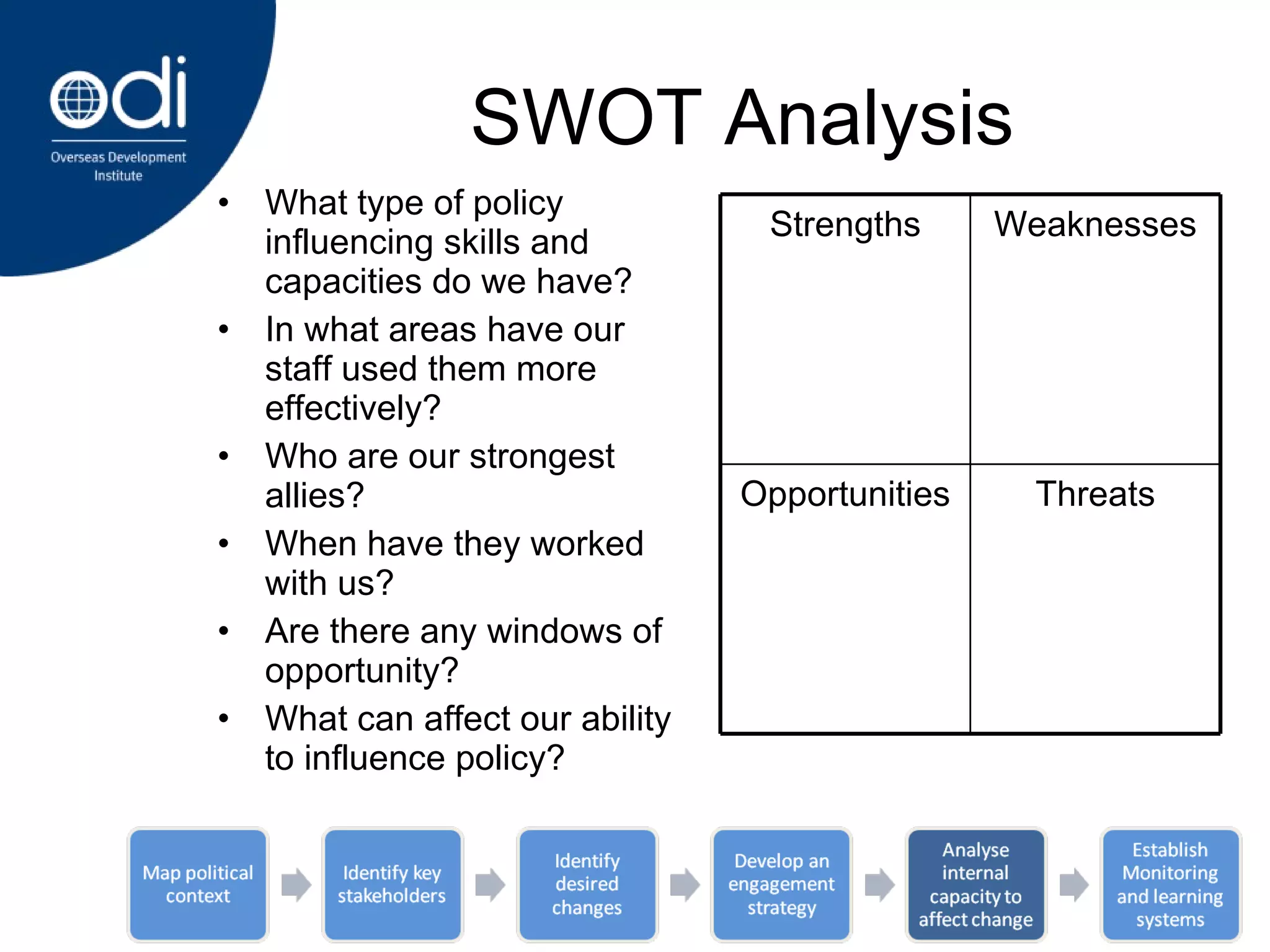

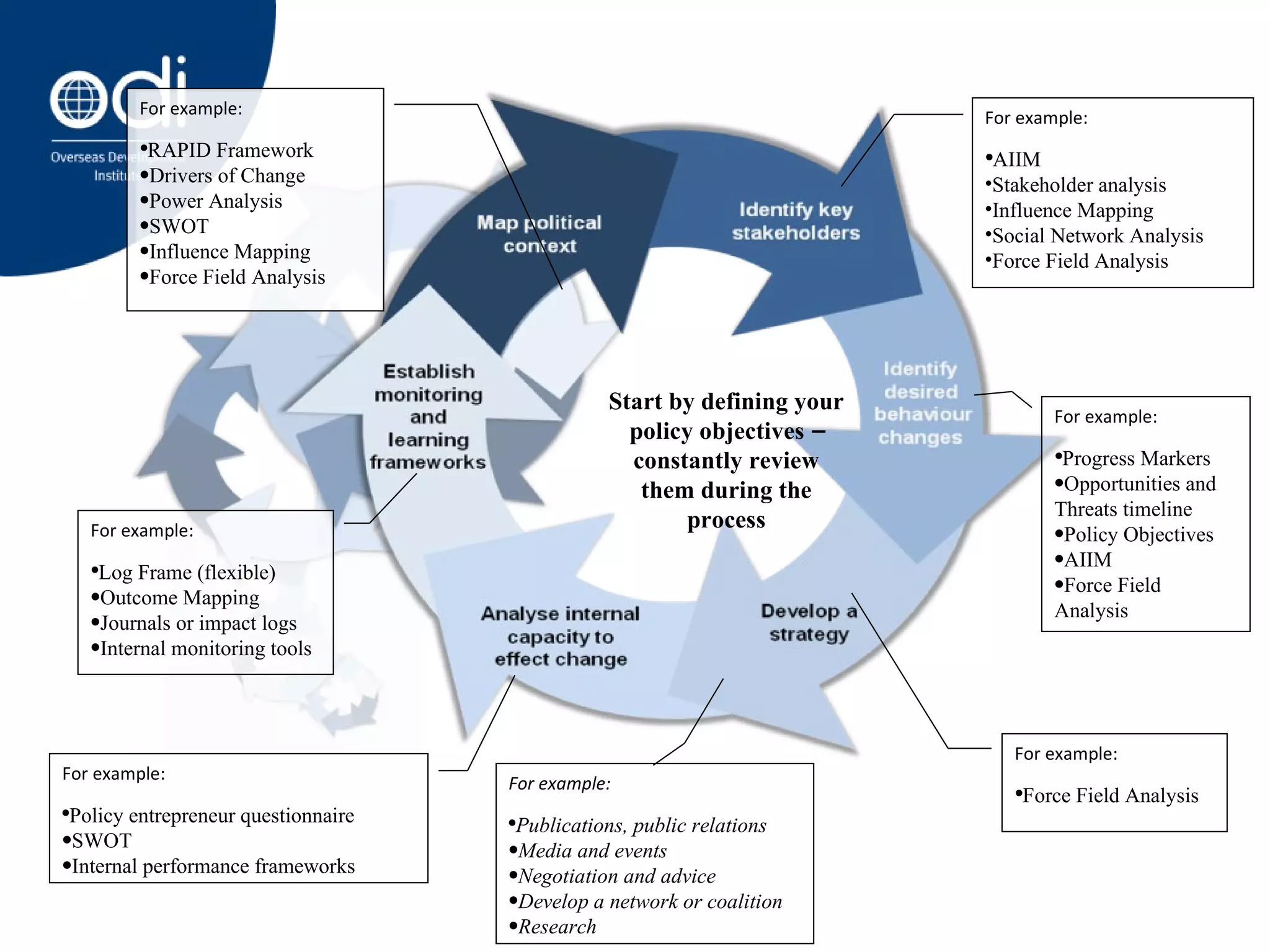

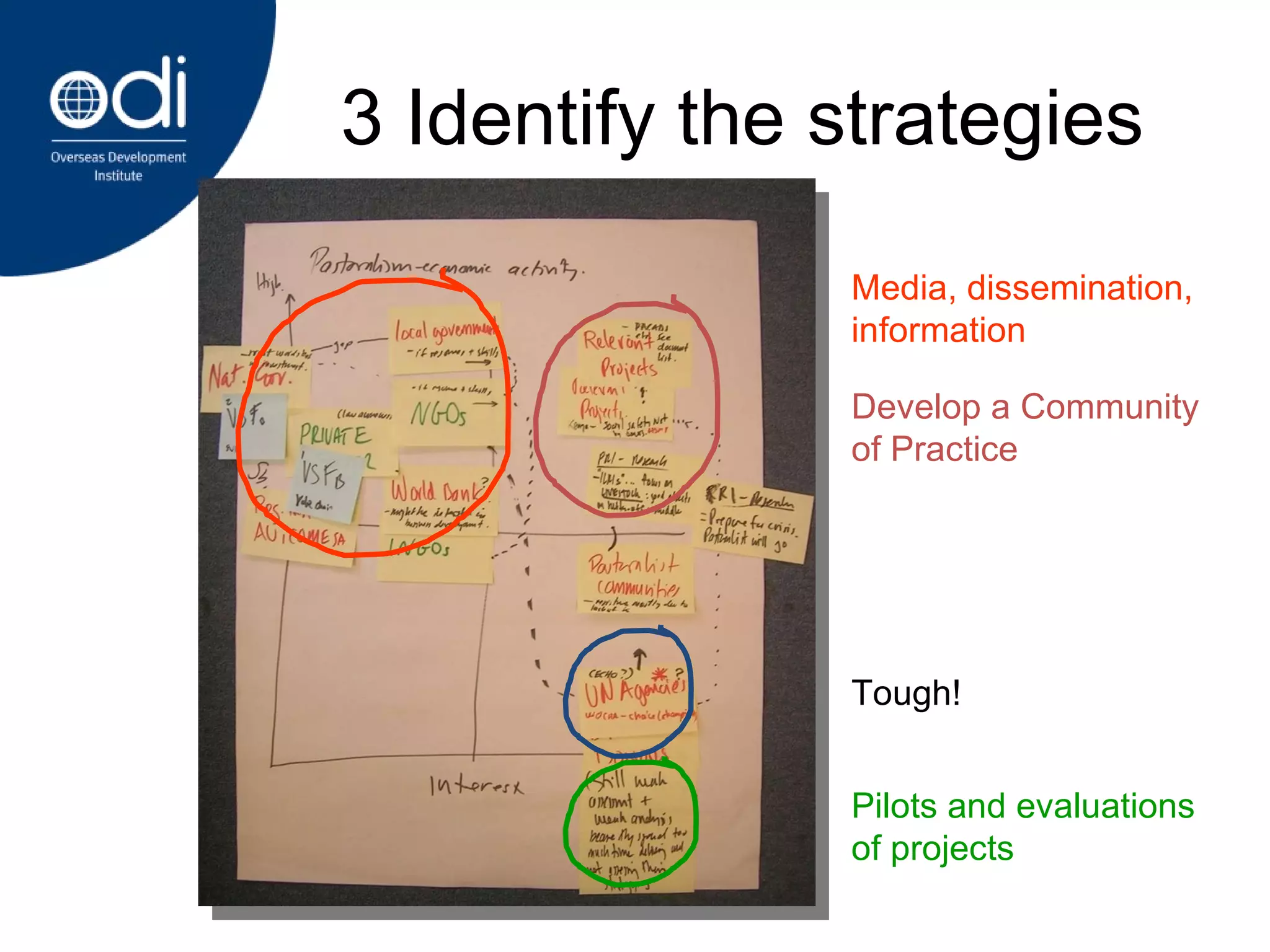

- Presentation of frameworks for analyzing the political context, evidence, and links between policy and research communities when influencing policy

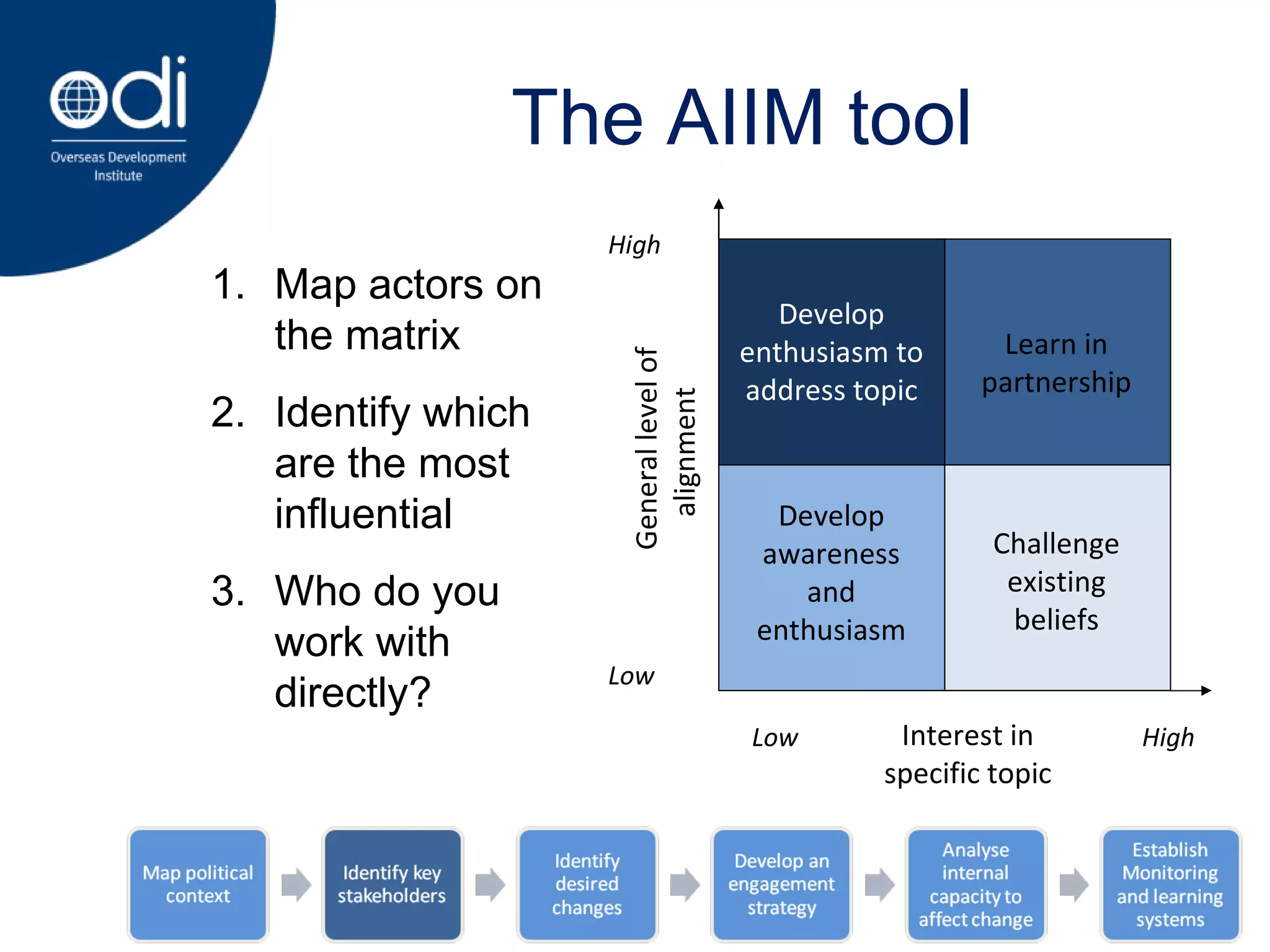

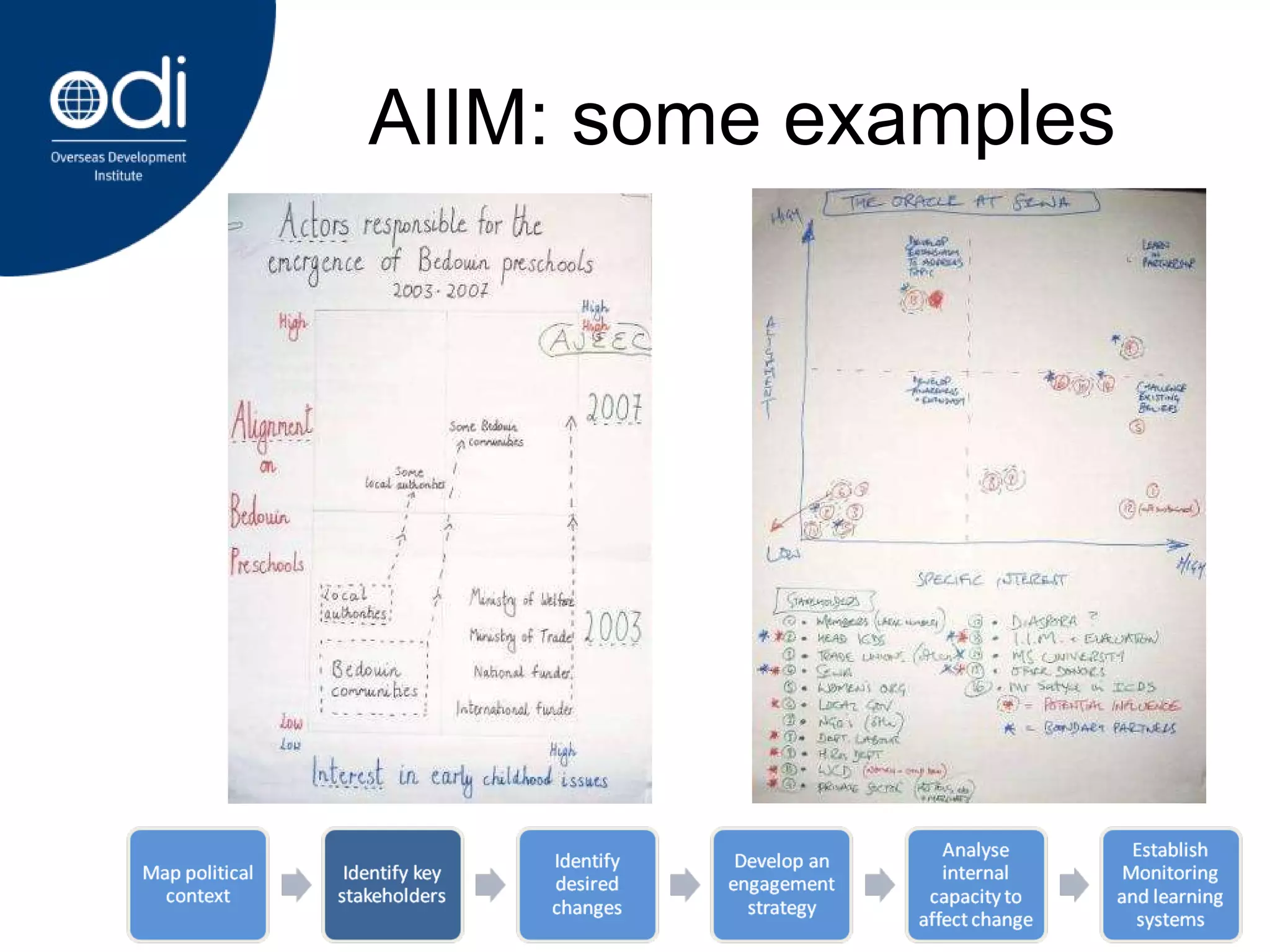

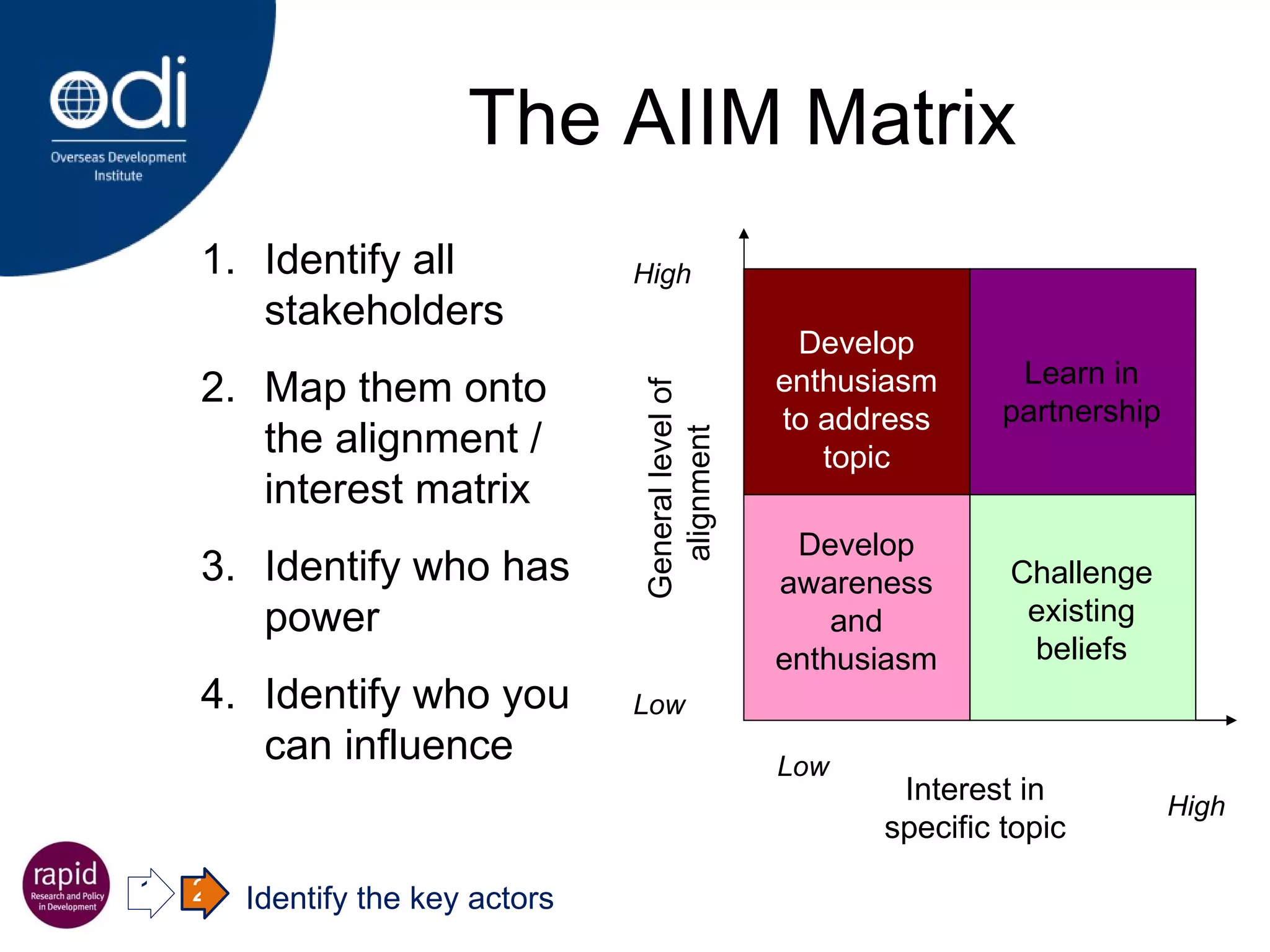

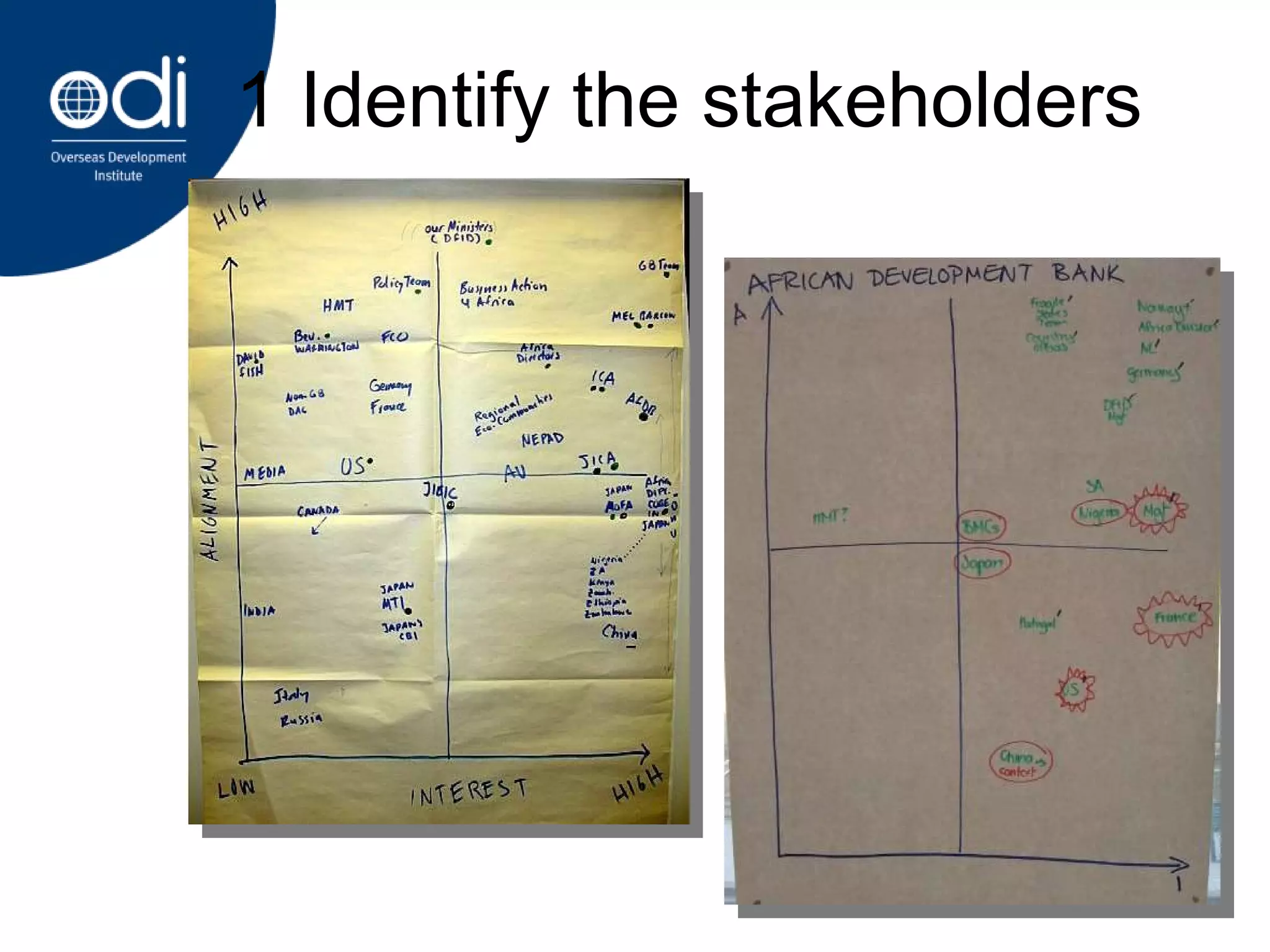

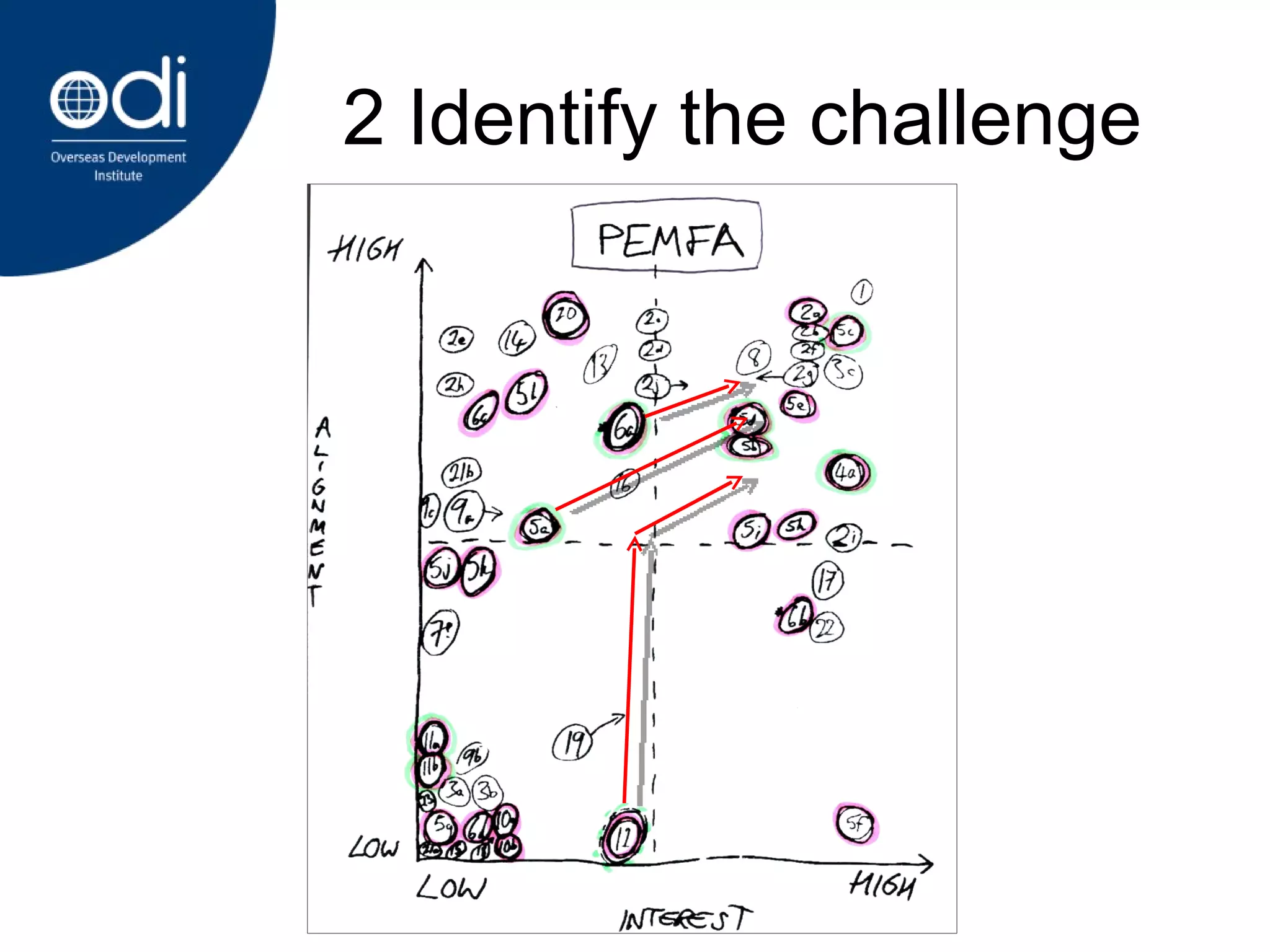

- Discussion of tools for strategic policy engagement including the Alignment, Interest and Influence Matrix to map stakeholders and prioritize targets.

![Storytelling At your table and with your neighbour, describe a story about a policy process that you’ve been engaged with What was the context? What was the aim of engagement? What actions did the process involve? What was the result of the actions? [10 minutes] Switch roles – if you were listening you should now tell the story [10 minutes]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arlf-tutorial2-091102070107-phpapp02/75/Acacia-Research-and-Learning-Forum-Tutorial-2-3-2048.jpg)

![Storytelling Then coming together with the rest of the table, from your collective experience, identify key lessons for effective policy engagement. Write 1 lesson on 1 card Identify about 6 lessons [20 min] Feedback Each table to present two cards in turn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arlf-tutorial2-091102070107-phpapp02/75/Acacia-Research-and-Learning-Forum-Tutorial-2-4-2048.jpg)

![Thank you! [email_address]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arlf-tutorial2-091102070107-phpapp02/75/Acacia-Research-and-Learning-Forum-Tutorial-2-44-2048.jpg)