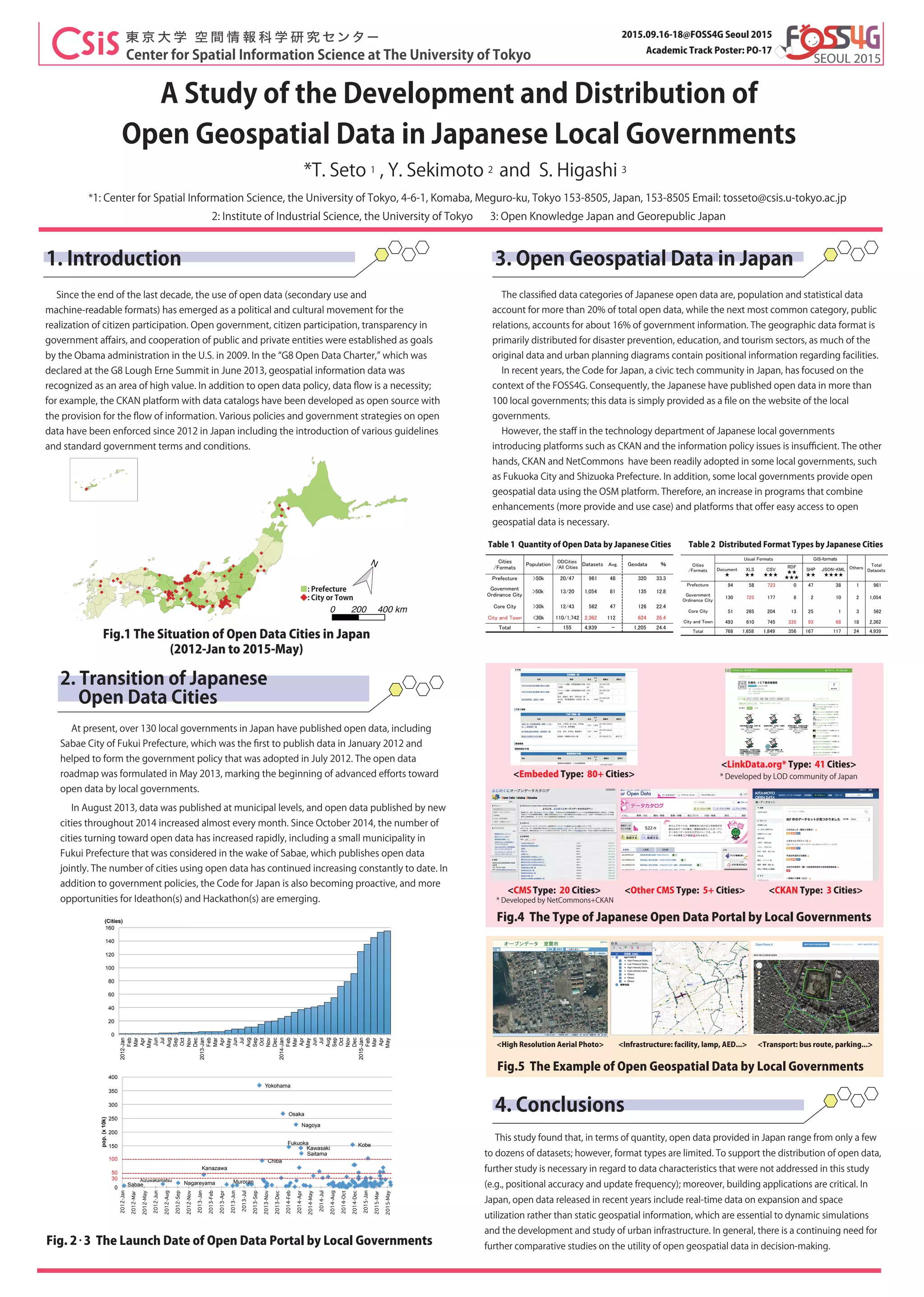

This document summarizes a study of open geospatial data development and distribution in Japanese local governments. It finds that over 130 local governments have published open data, with the first being Sabae City in 2012. The number of publishing cities increased rapidly from 2014 onward. Geographic data is primarily distributed for disaster prevention, education, and tourism purposes. While the quantity of open data has increased, the formats remain limited. Further development of applications and studies of data characteristics are needed to better support open data distribution.