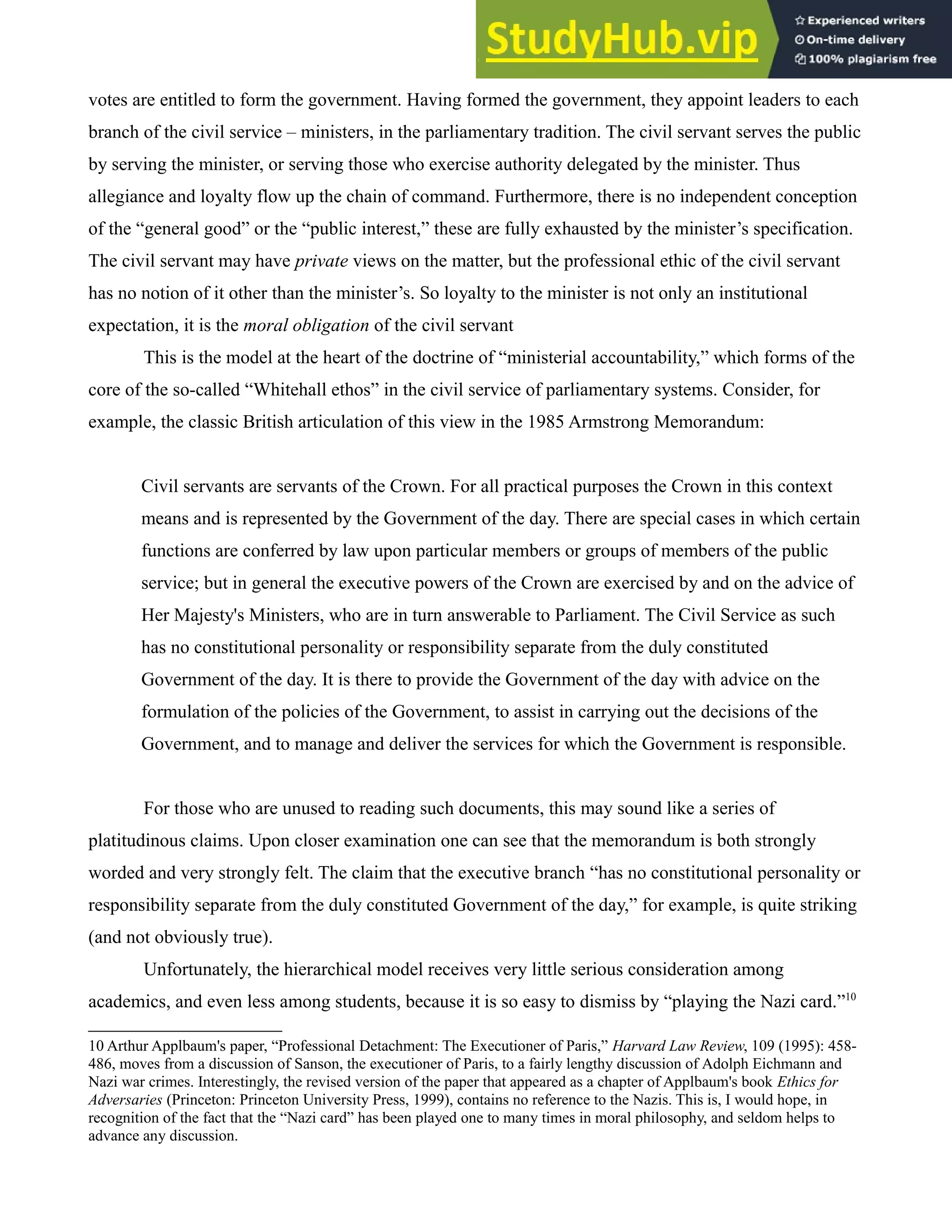

This document provides an introduction to developing a framework for ethics in public administration. It notes that while business ethics is a well-developed field, ethics for civil servants has received less attention. It aims to address this gap by outlining some key differences between business and government that complicate developing universal ethical guidelines for civil servants. These include differences between political systems, the wide variety of government departments and roles, and the civil service's traditional reliance on internal culture rather than formal ethics education. The document seeks to clarify civil servants' core obligations and how they should resolve conflicts between serving elected officials, the public, and professional norms.

![A General Framework for the Ethics of Public Administration*

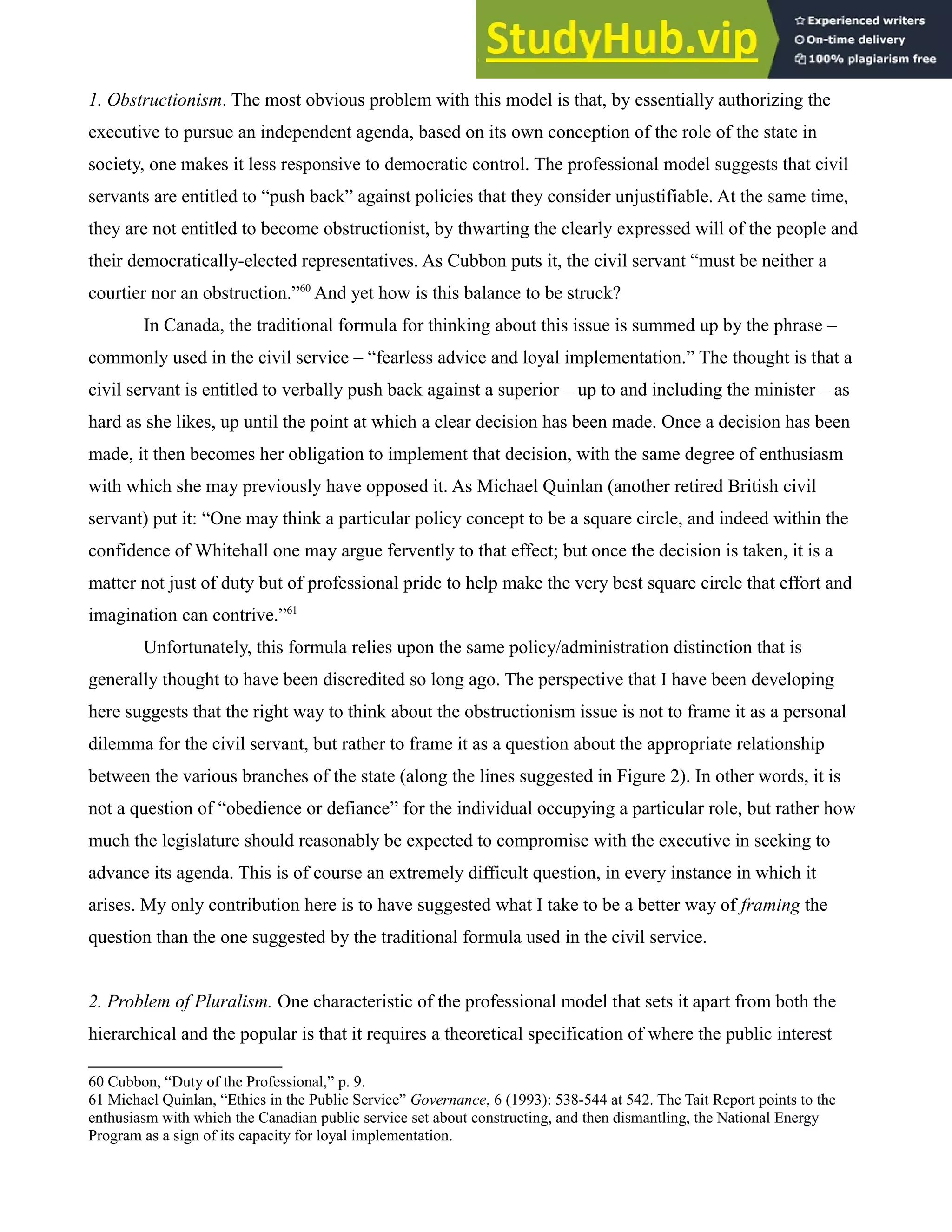

Joseph Heath

Department of Philosophy and

School of Public Policy and Governance

University of Toronto

[draft Jan. 30, 2014]

Compared to the field of business ethics, the field of “public administration ethics,” or “ethics

for civil servants,” is woefully undeveloped. There are several scholarly journals dedicated exclusively

to the subject of business ethics, not to mention dozens of textbooks and a steady of flow of titles from

both academic and popular presses. The ethics of public administration, by contrast, attracts only a

small fraction of this concern. Furthermore, while there is some literature on “public integrity,” the

discussion tends to focus disproportionately on the behavior of politicians and elected officials, to the

occlusion of any concern over the behavior of civil servants. Some attempts have been made to develop

a general framework for the “ethics of management” or “ethics of bureaucratic organizations” that

would encompass both private and public sectors.1

Yet no approach has been developed that is

specifically tailored to the institutional quiddities of the public service.

There are of course reasons for this. Business ethics is primarily concerned with the moral

obligations of relatively senior managers in standard, typically publicly traded, business corporations.

Despite certain variations, the basic structure of the corporation is surprisingly standard across national

jurisdictions.2

Thus it is possible to make fairly robust generalizations about “the corporation,” and to

sustain an international dialogue that is not overly constrained by differences in local practice. The

same cannot be said for the civil service, where even among liberal democracies there are enormous

differences in institutional structure. The internal operations of presidential systems, for instance

(where the head of the executive branch of government is independent and directly elected by the

people) are so different from those in parliamentary systems (where the executive is not fully divorced

from the legislative, and enjoys no independent democratic legitimacy) that it limits the extent to which

lessons learned in one system can be generalized to the other.

The modern welfare state also engages in an extraordinarily wide range of activities, many of

which have very little in common with one another. Some departments, agencies or state-owned

* This paper has benefited from comments and advice from audiences at Carlton University and the Princeton University

Center for Human Values. Special thanks as well to Alex Himelfarb and Andrew Stark for helpful feedback, to Sareh

Pouryousefi for many conversations, and to students over the years at the School of Public Policy and Governance at the

University of Toronto.

1 E.g., Allan Buchanan, “Toward a Theory of the Ethics of Bureaucratic Organizations,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 6

(1996): 419-440.

2 See Reinier Kraakman, John Armour, Paul Davies, Luca Enriques, Henry B. Hansmann, Gérard Hertig, Klaus J. Hopt,

Hideki Kanda and Edward B. Rock, The Anatomy of Corporate Law, 2nd

edn. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ageneralframeworkfortheethicsofpublicadministration-230805222803-ea186cdd/75/A-General-Framework-For-The-Ethics-Of-Public-Administration-1-2048.jpg)