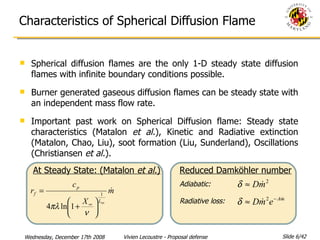

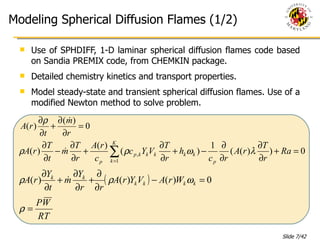

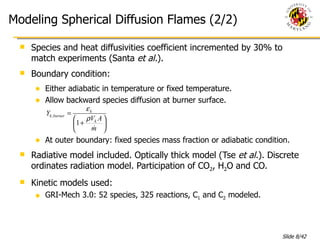

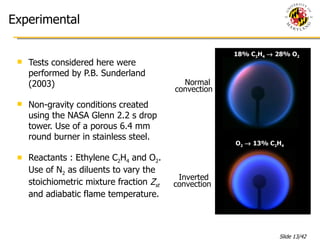

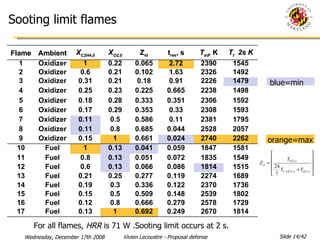

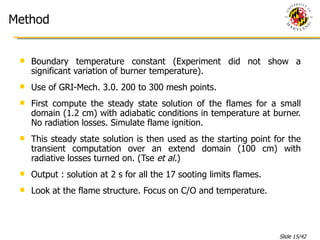

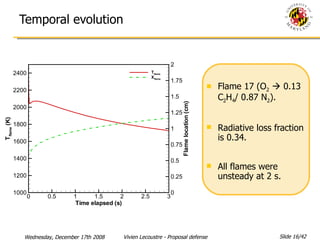

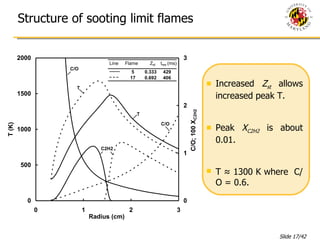

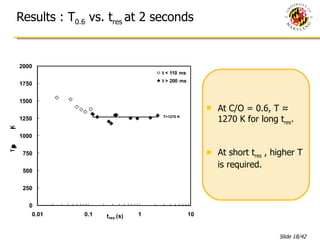

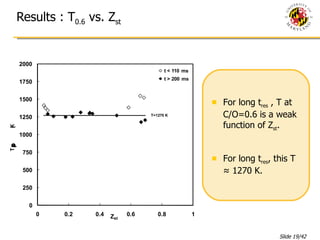

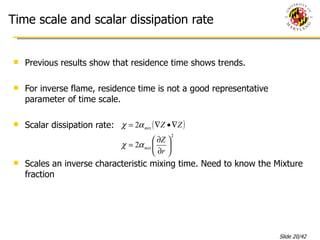

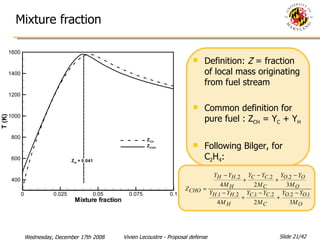

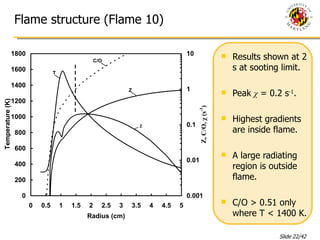

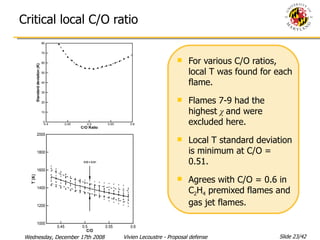

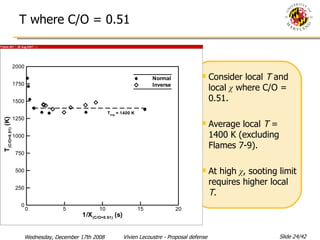

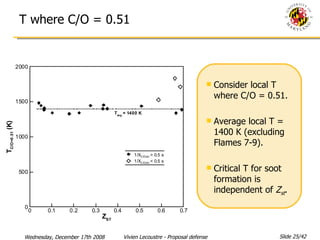

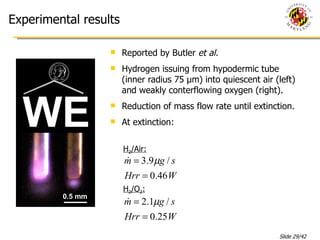

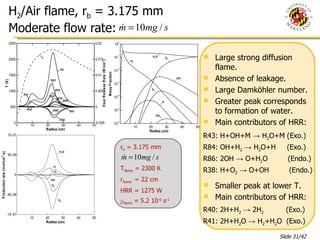

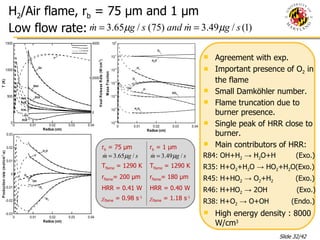

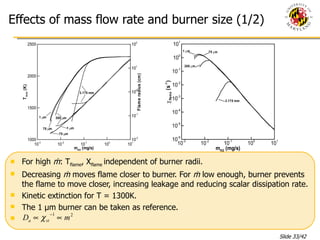

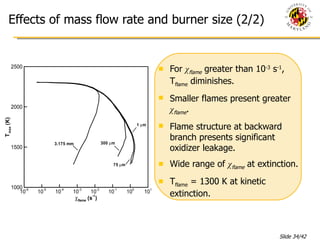

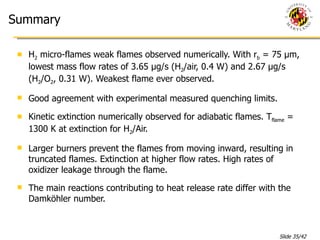

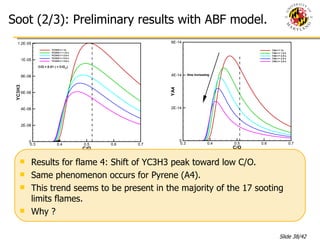

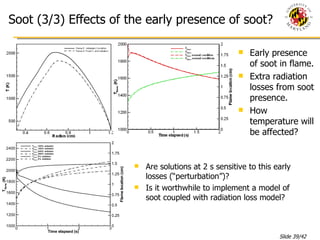

The document presents a numerical investigation of spherical diffusion flames. It summarizes past work on spherical diffusion flames and outlines the objectives of studying soot formation in ethylene flames and weak hydrogen micro-flames. For ethylene flames, the investigation finds that soot formation requires a local C/O ratio of at least 0.51 and temperature of around 1400K. For hydrogen micro-flames, it characterizes flames near the quenching limit and finds flame structure is similar to microgravity flames.