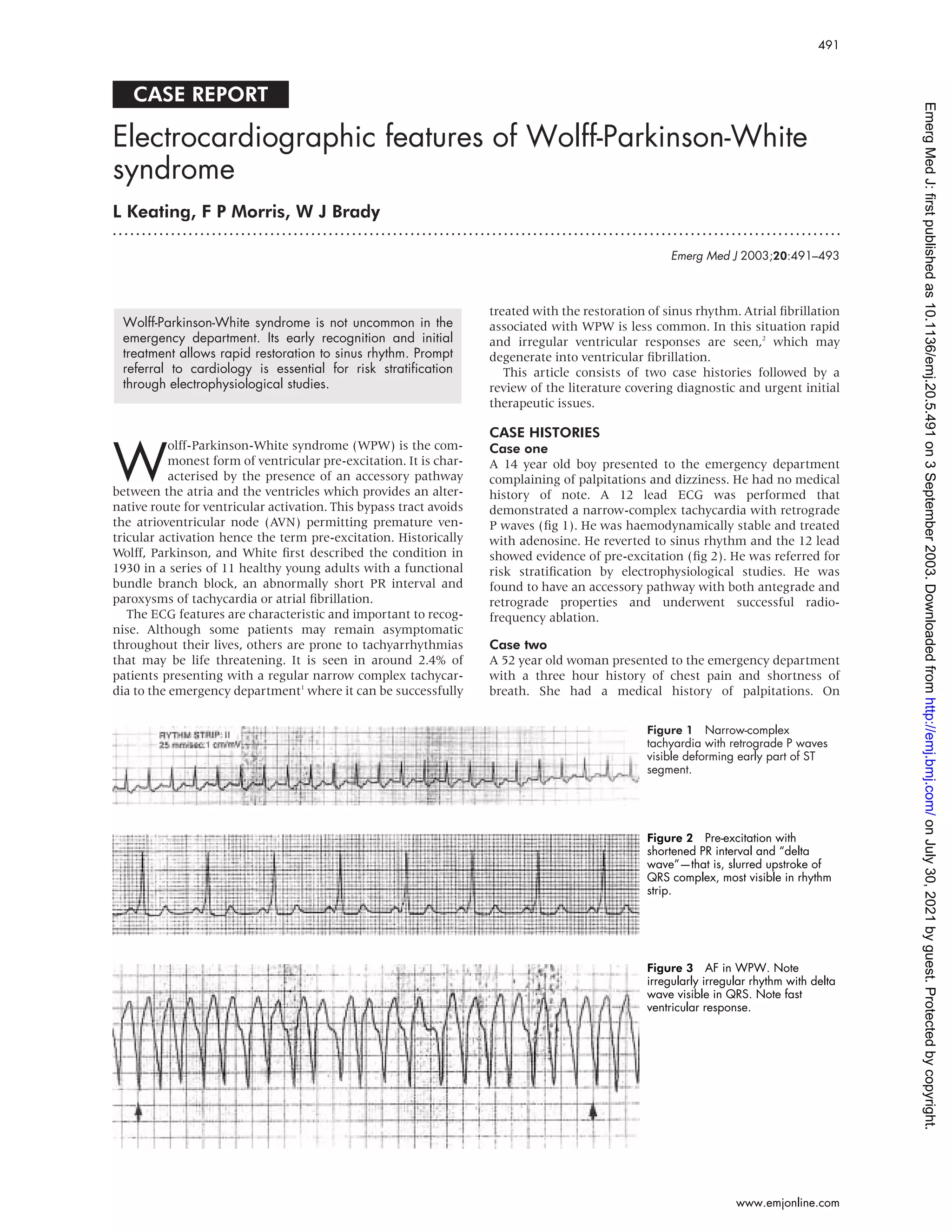

This document reports on two case studies of patients presenting with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW), a condition characterized by an extra electrical pathway between the atria and ventricles. The first case involved a 14-year-old boy who presented with palpitations and dizziness. Electrocardiogram showed narrow-complex tachycardia that was treated with adenosine. The second case was a 52-year-old woman who presented with chest pain, shortness of breath, and was hemodynamically compromised. Both patients underwent procedures to ablate the accessory pathways. The document then reviews the characteristic electrocardiographic features of WPW and treatments for arrhythmias associated with the