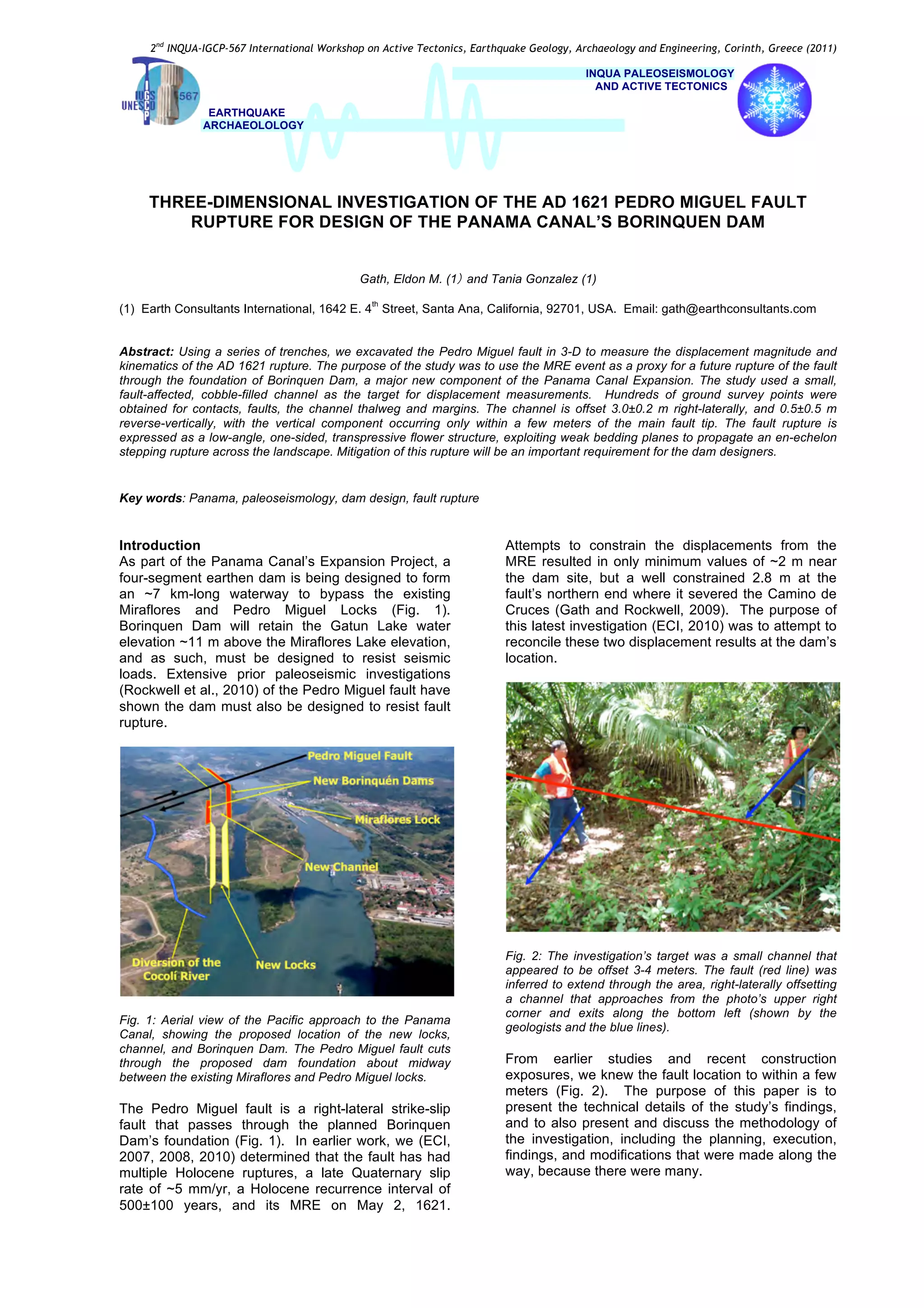

1) The study investigated the Pedro Miguel fault rupture from the 1621 earthquake using trenches to measure displacement of an offset channel.

2) Trenches revealed a complex fault structure with the channel displaced 3.0±0.2 m right-laterally and 0.5±0.5 m vertically near the fault tip.

3) The study provides important constraints on fault displacement at the site of the proposed Borinquen Dam for the Panama Canal expansion project to ensure its design accounts for potential fault rupture.