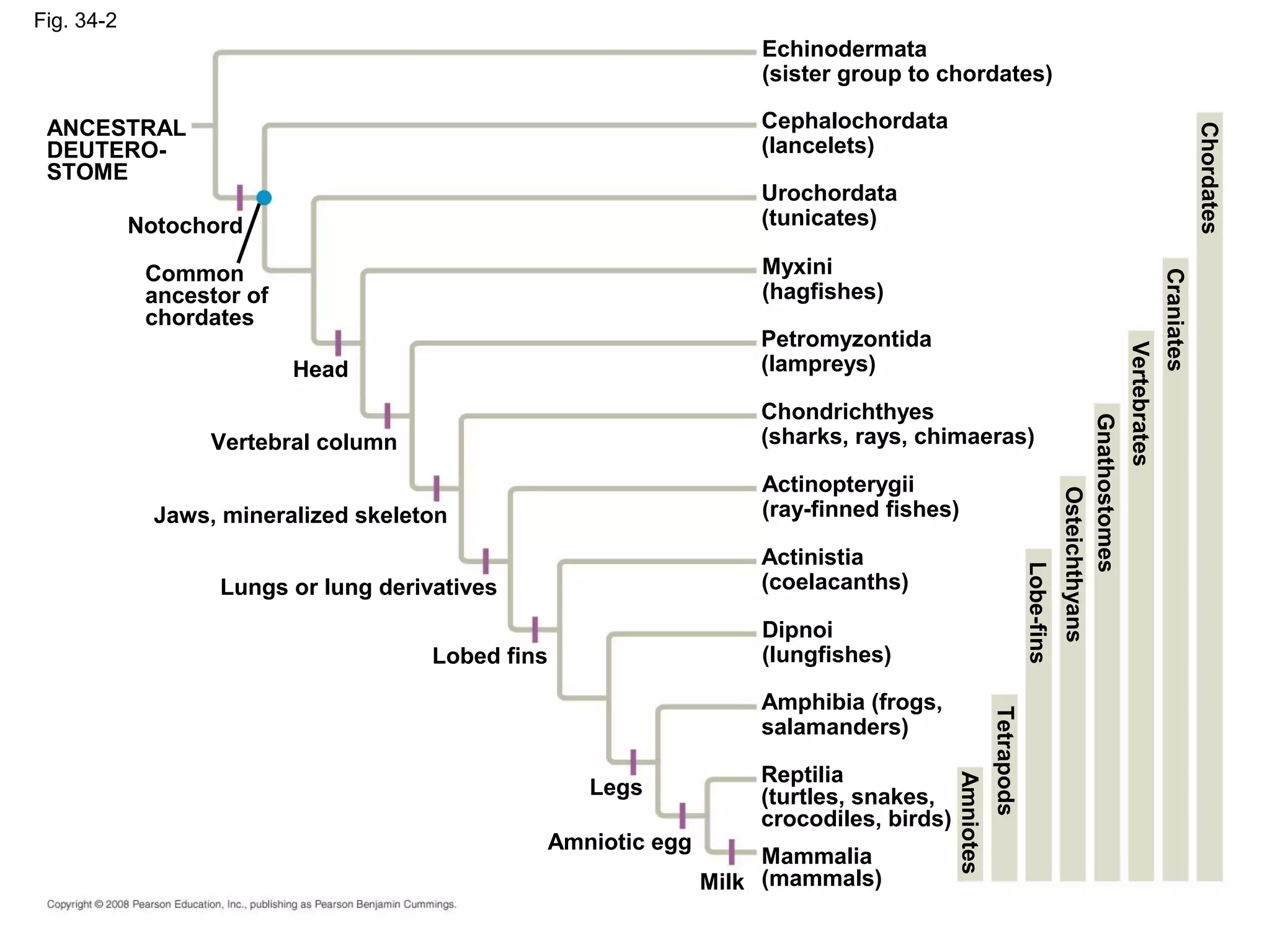

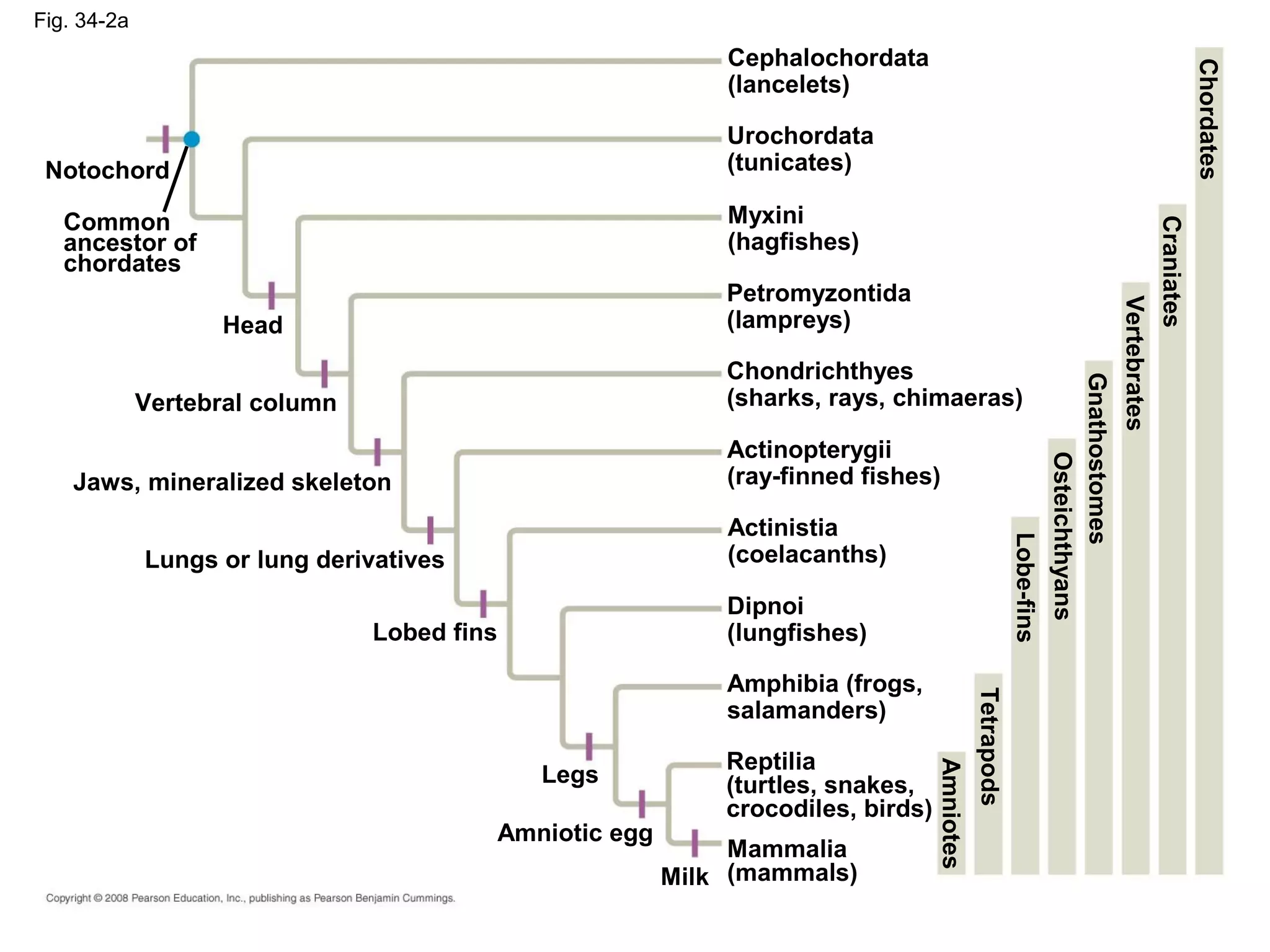

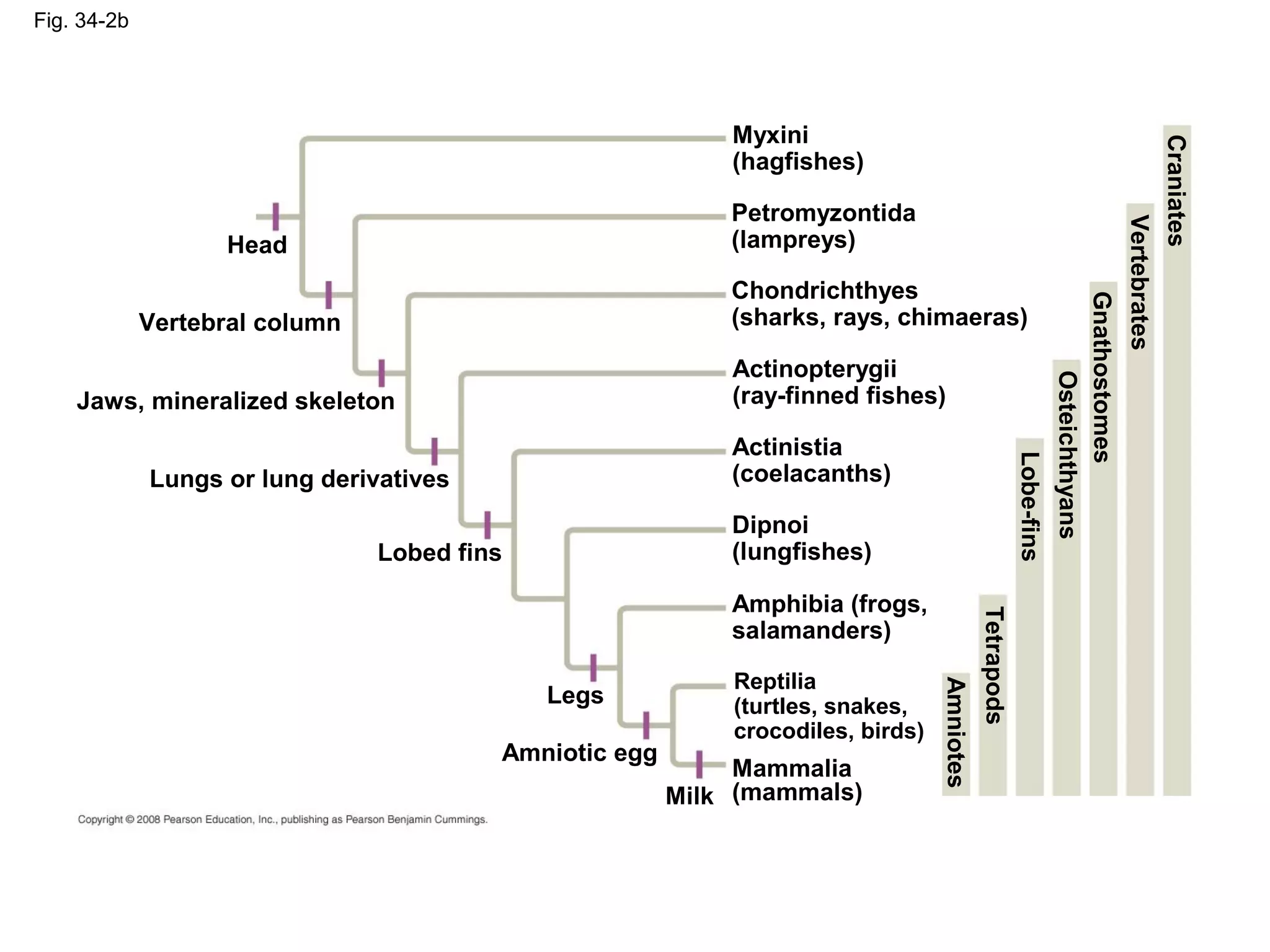

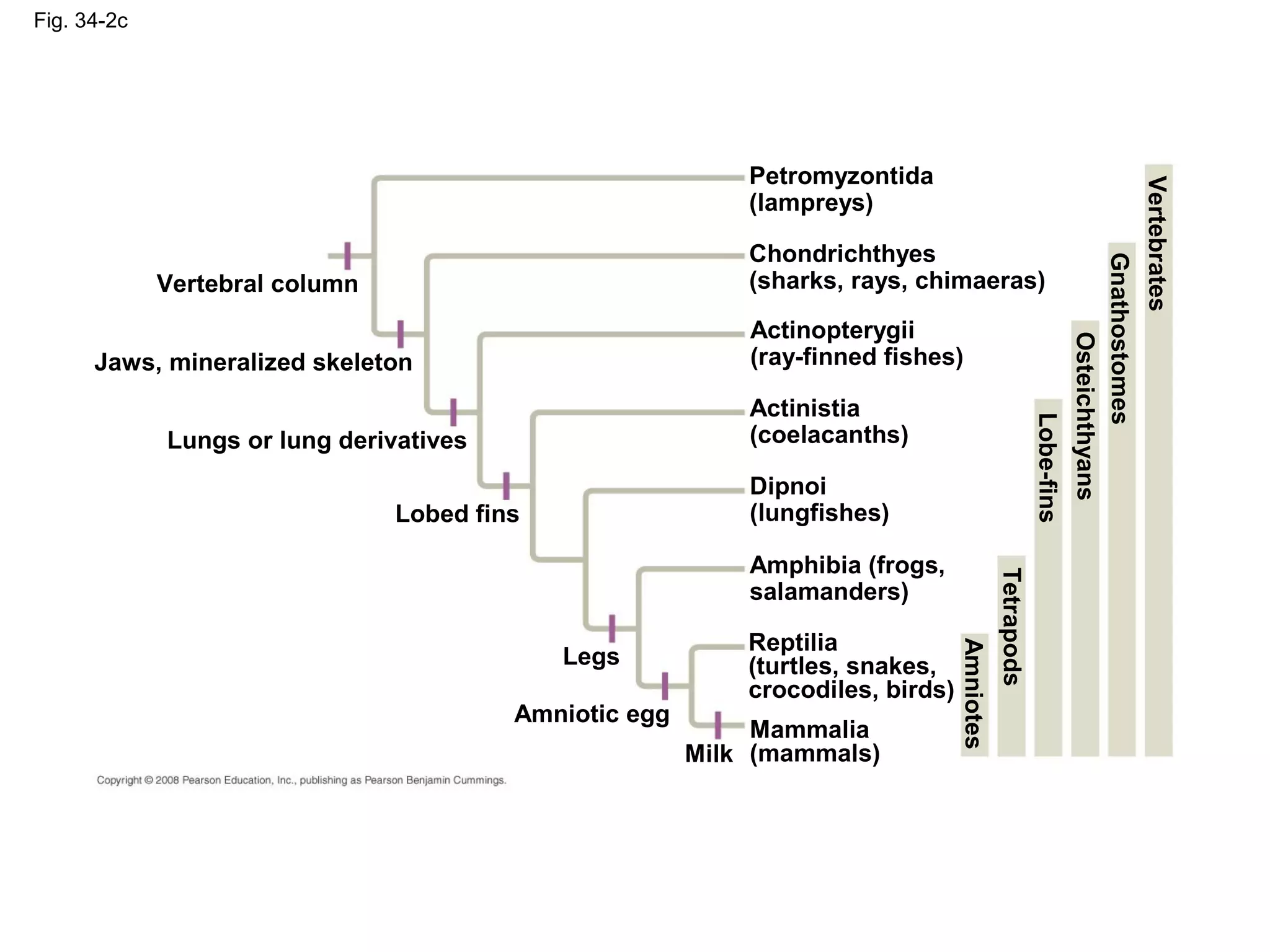

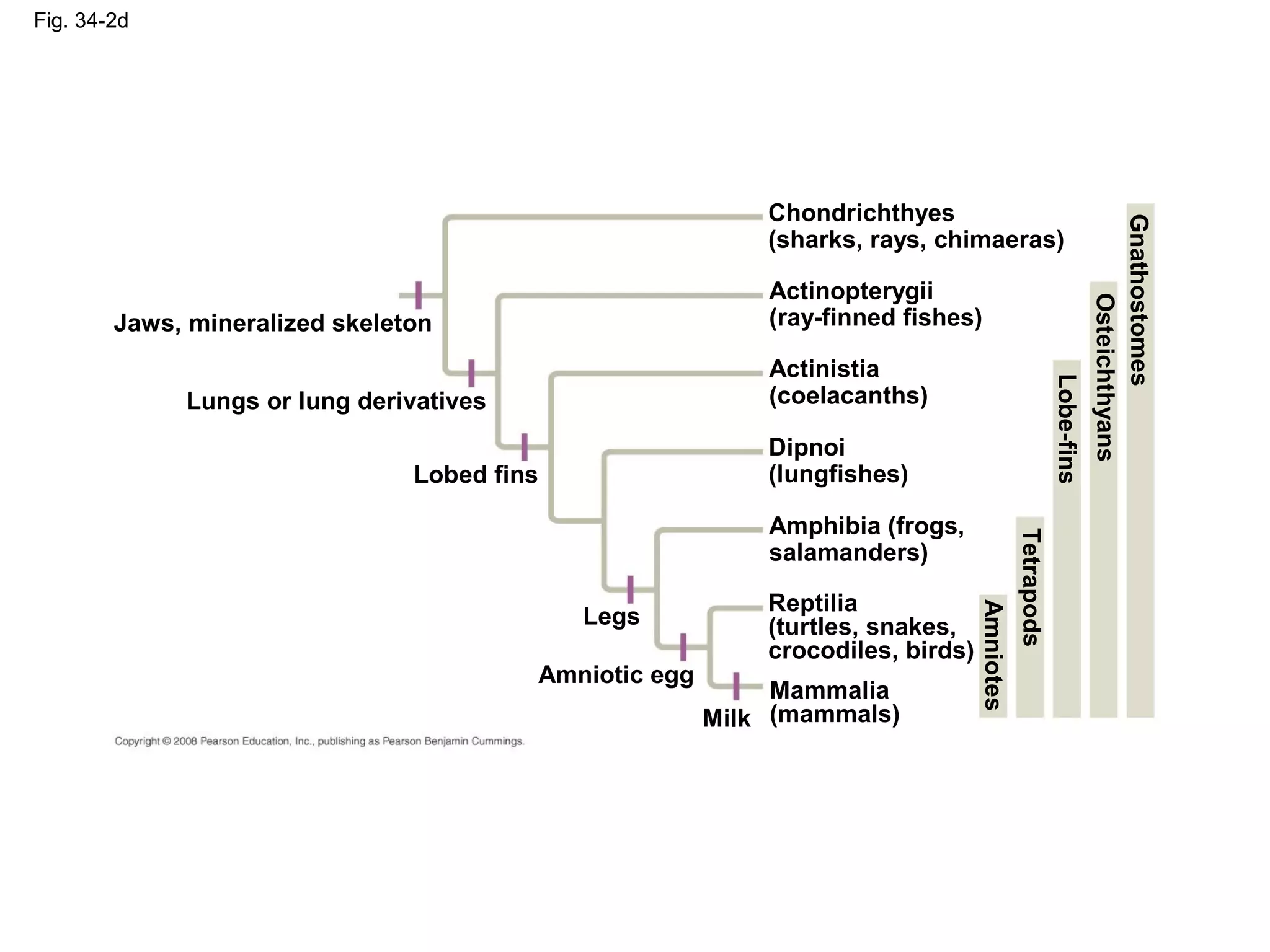

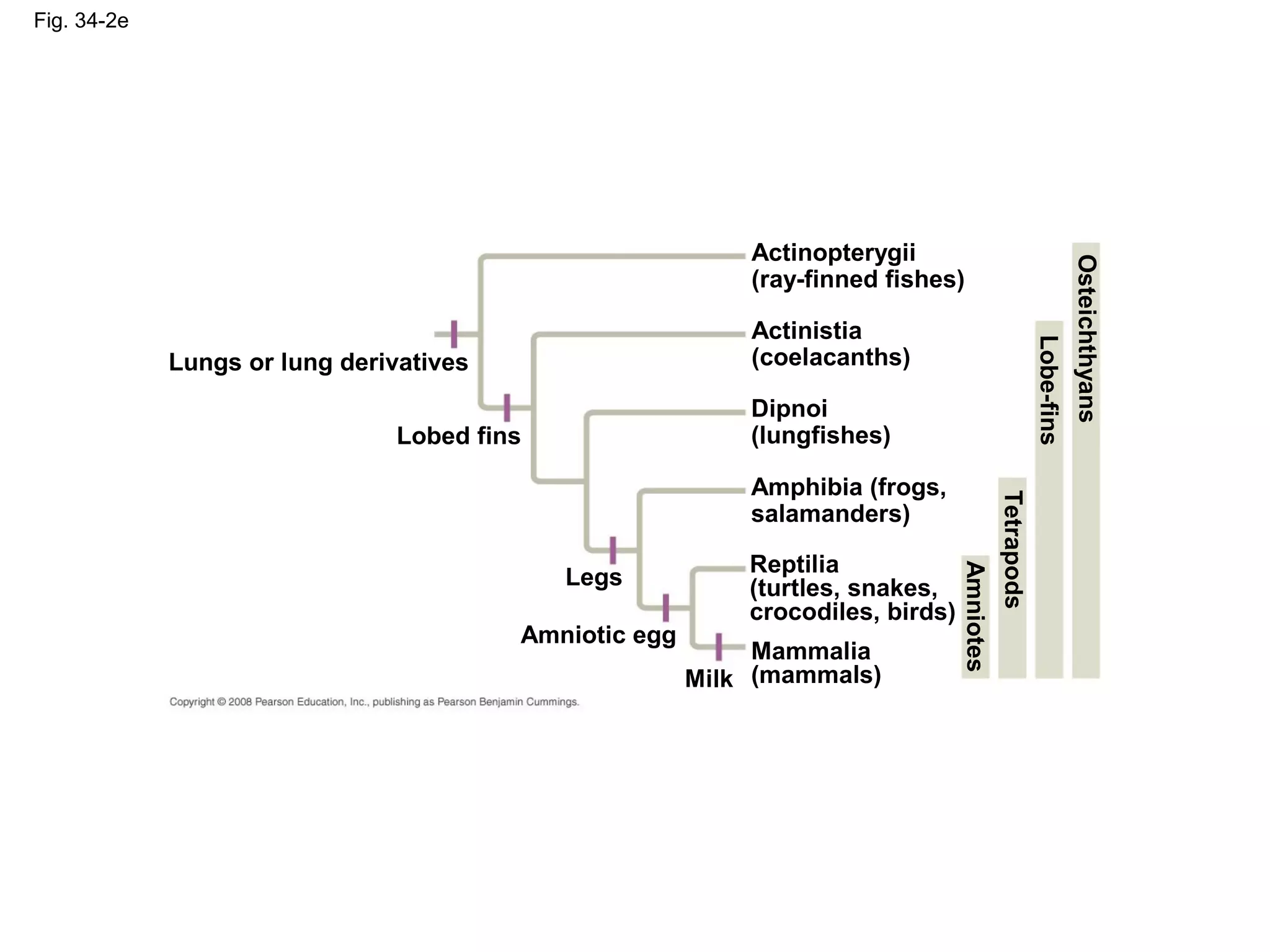

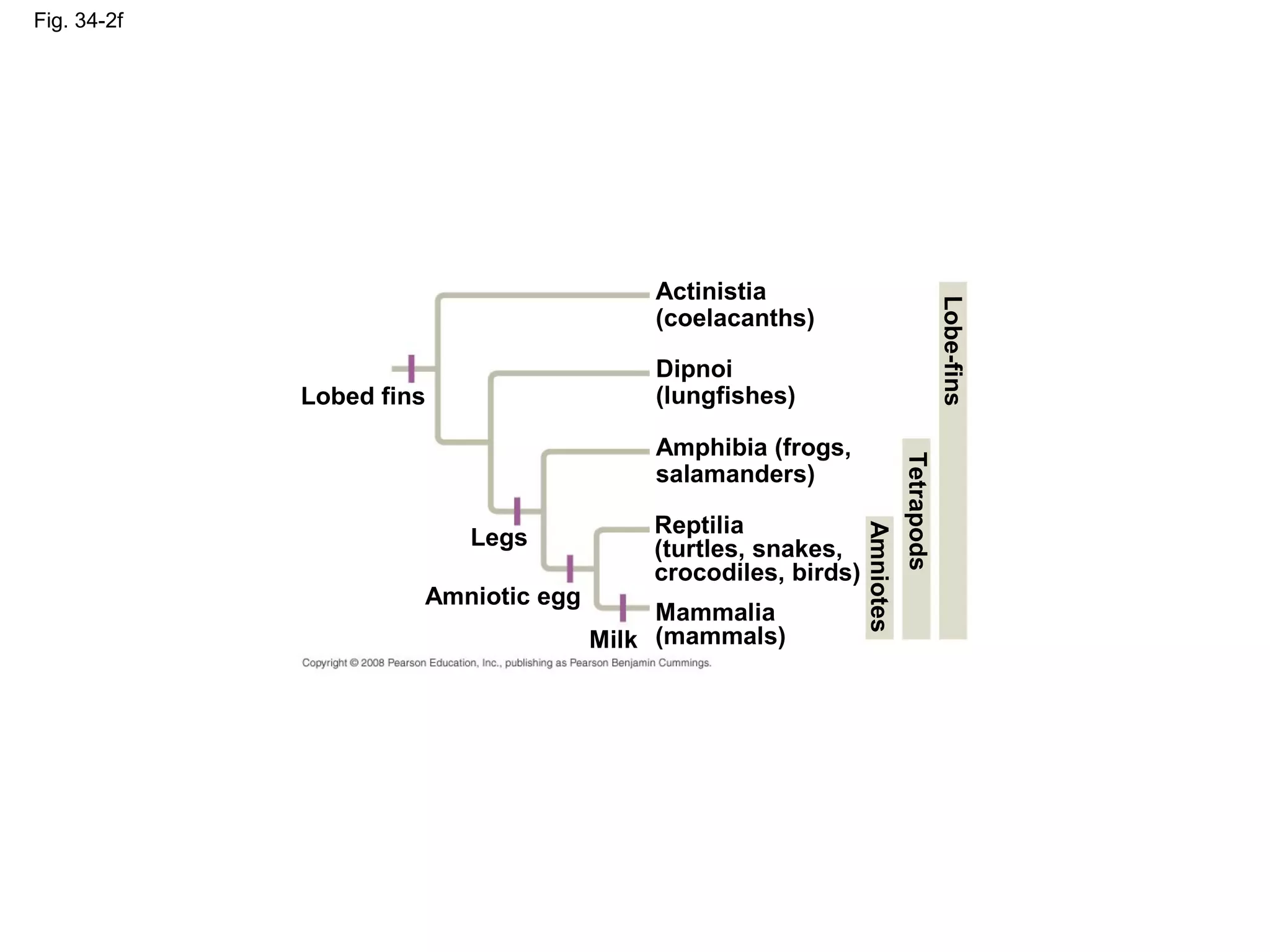

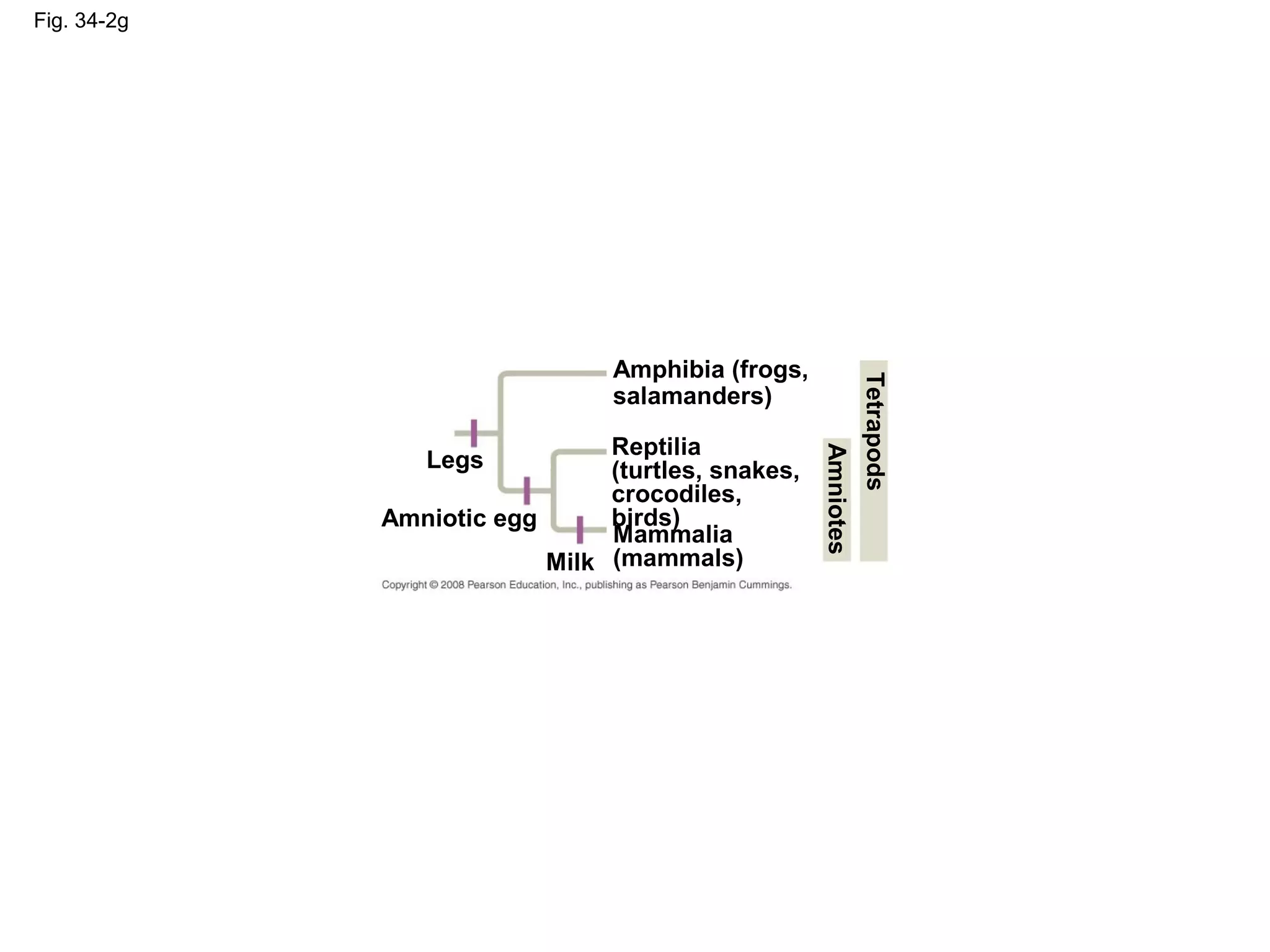

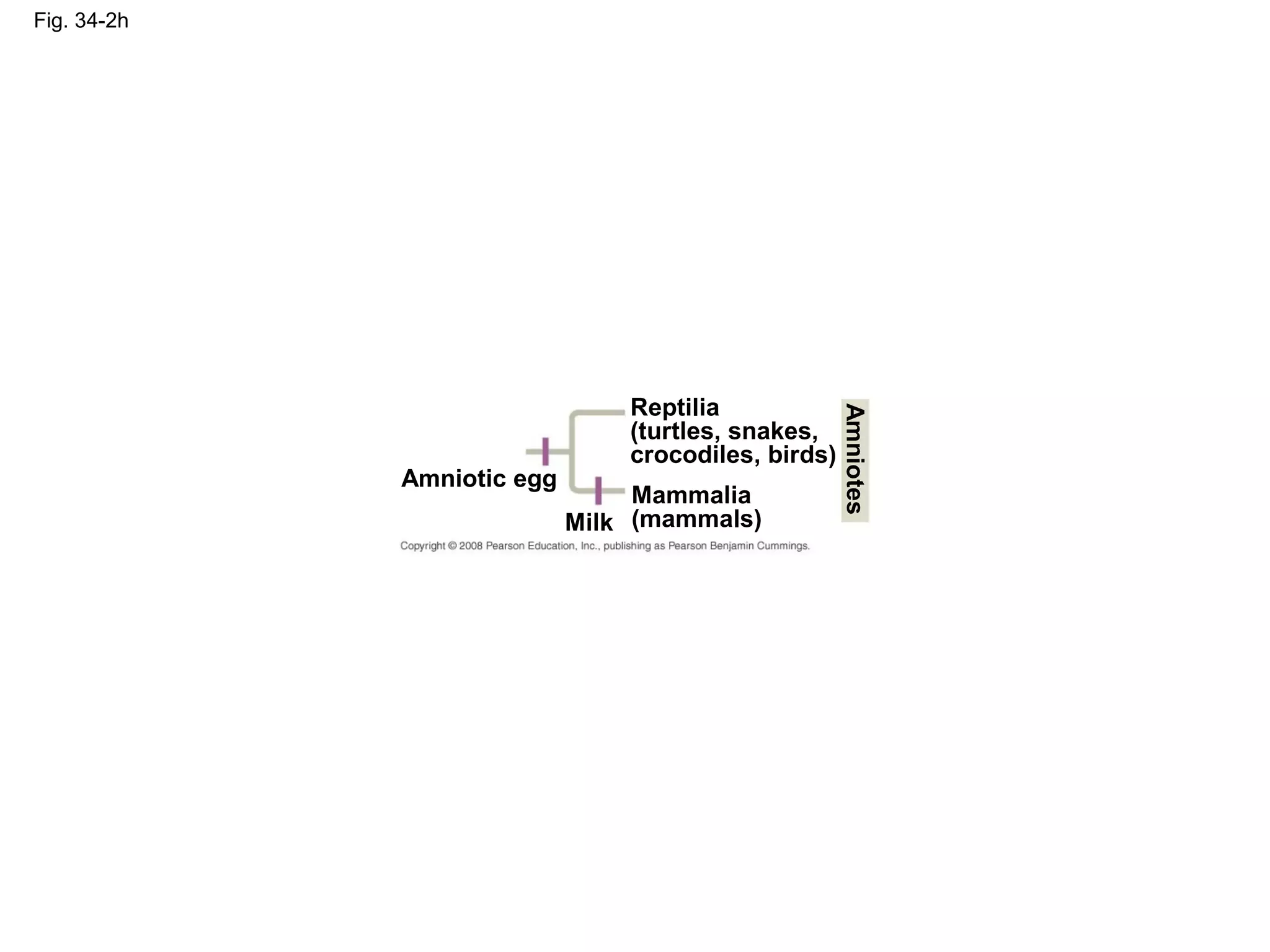

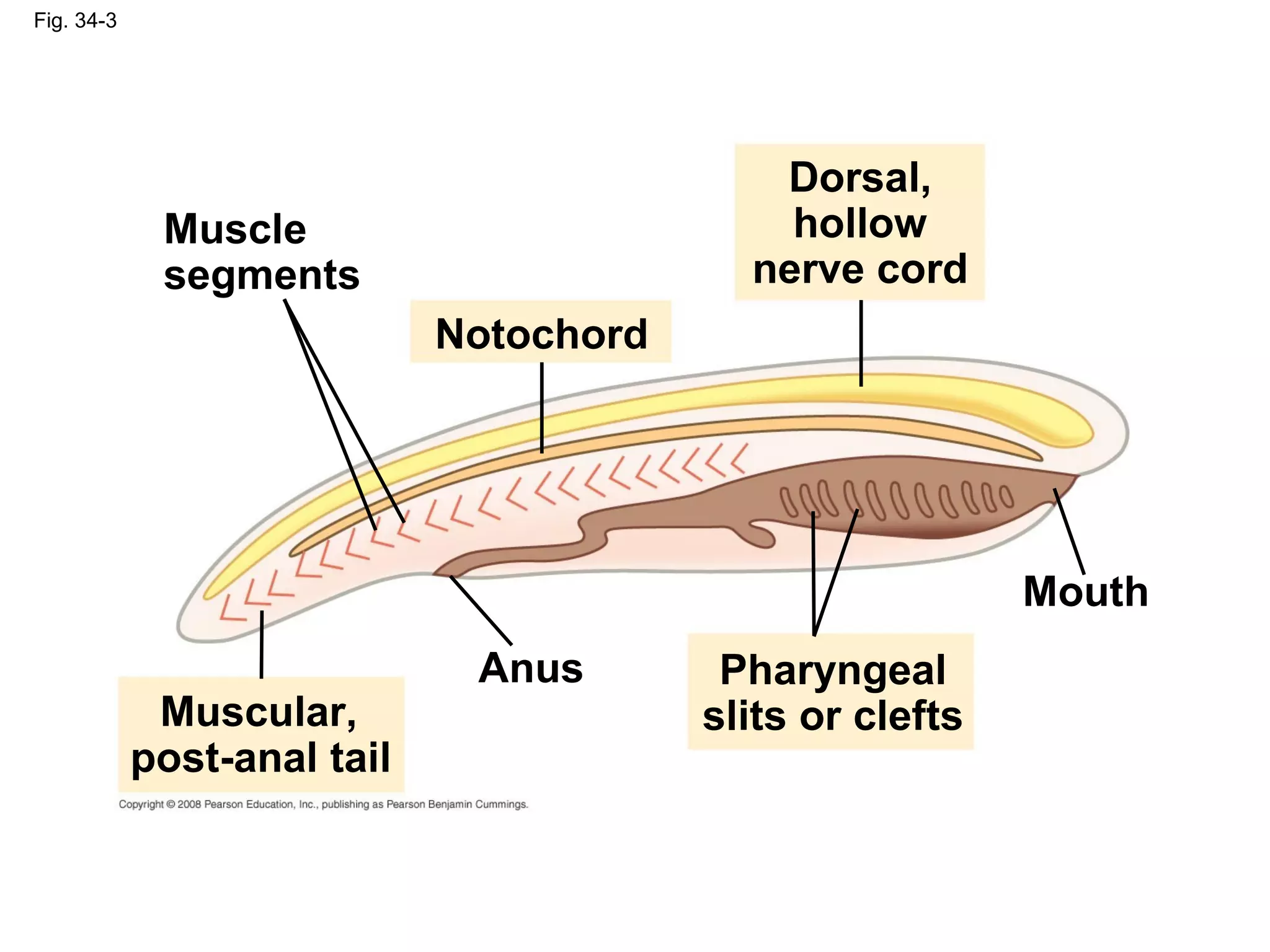

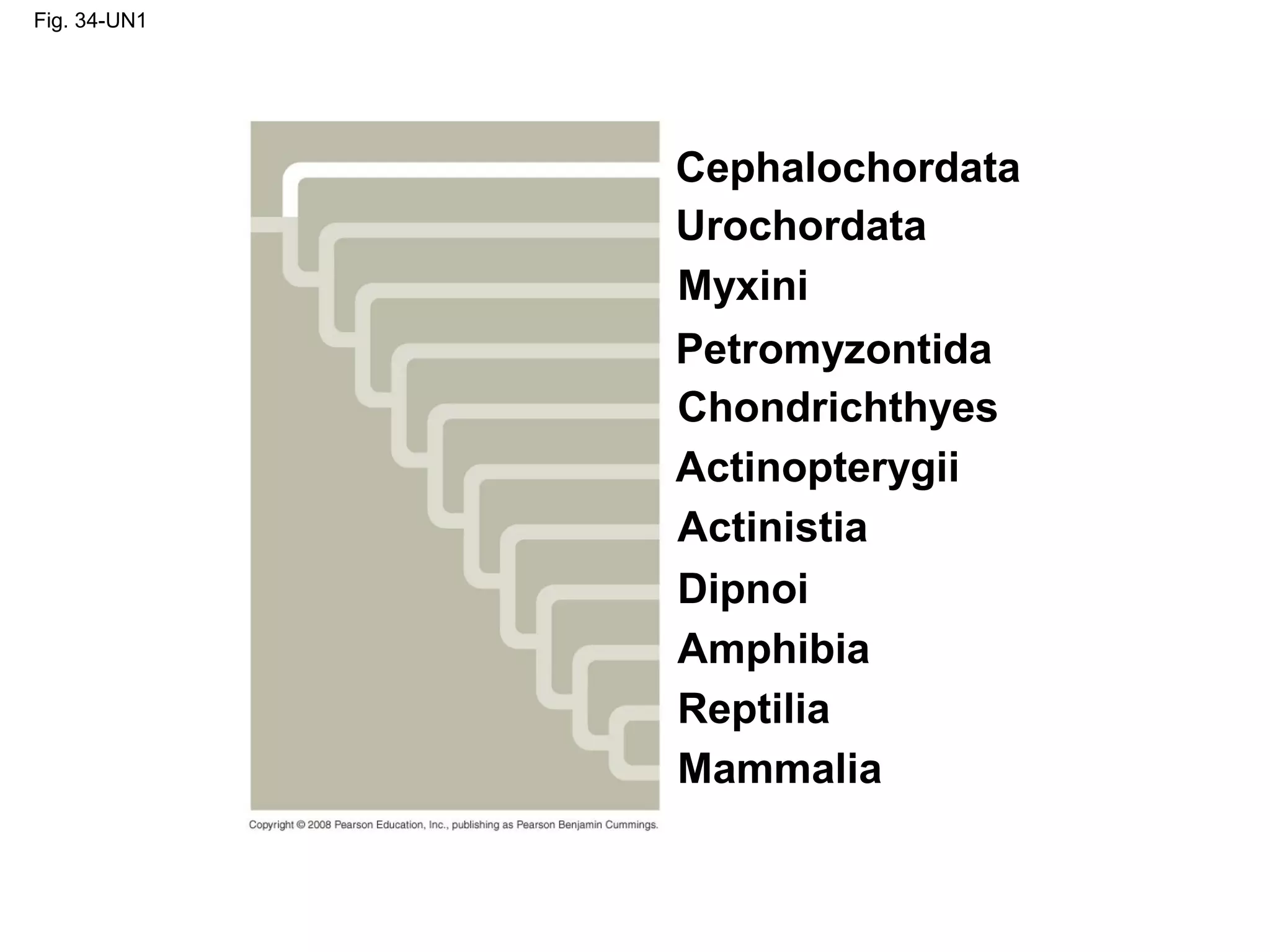

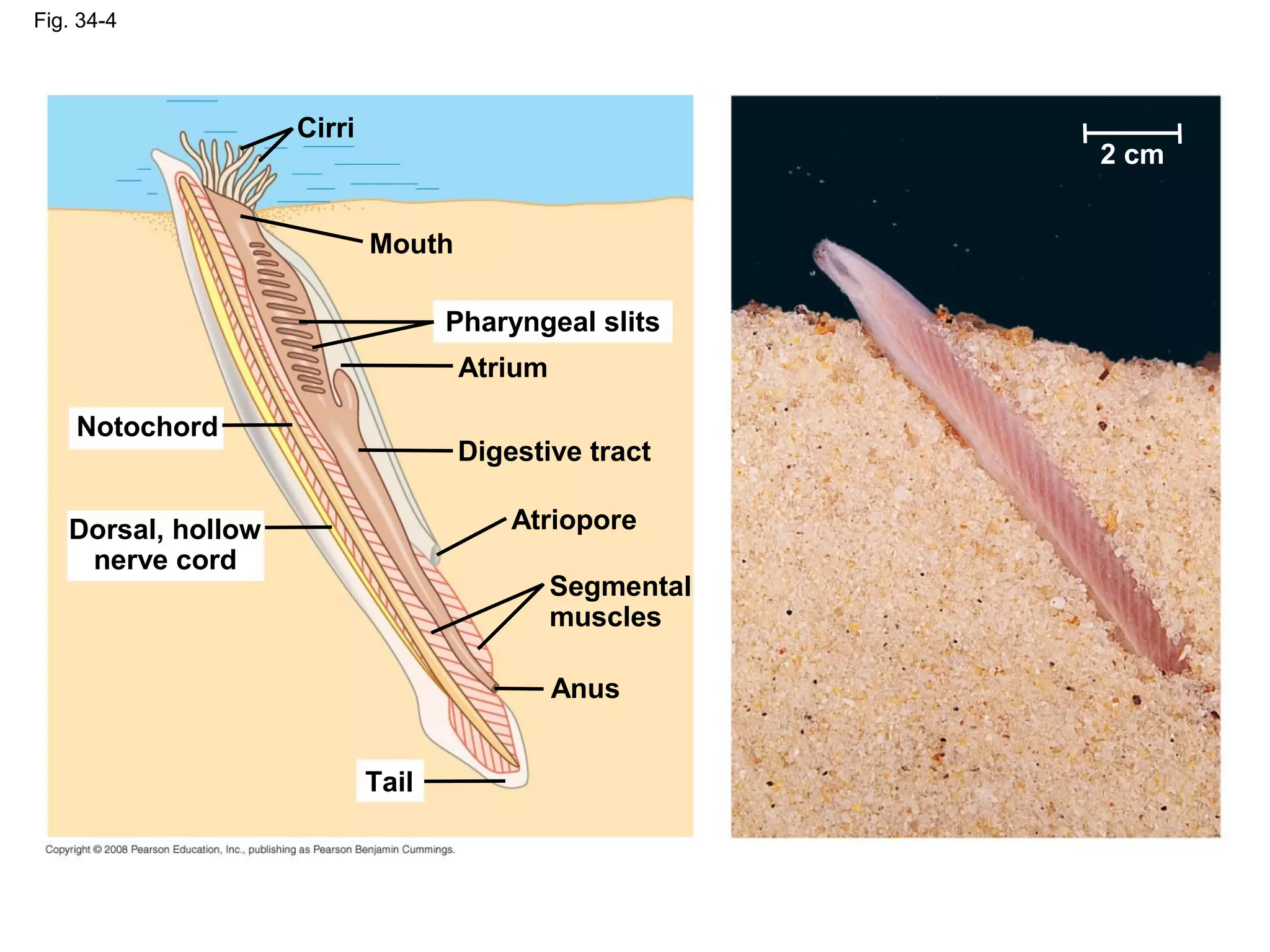

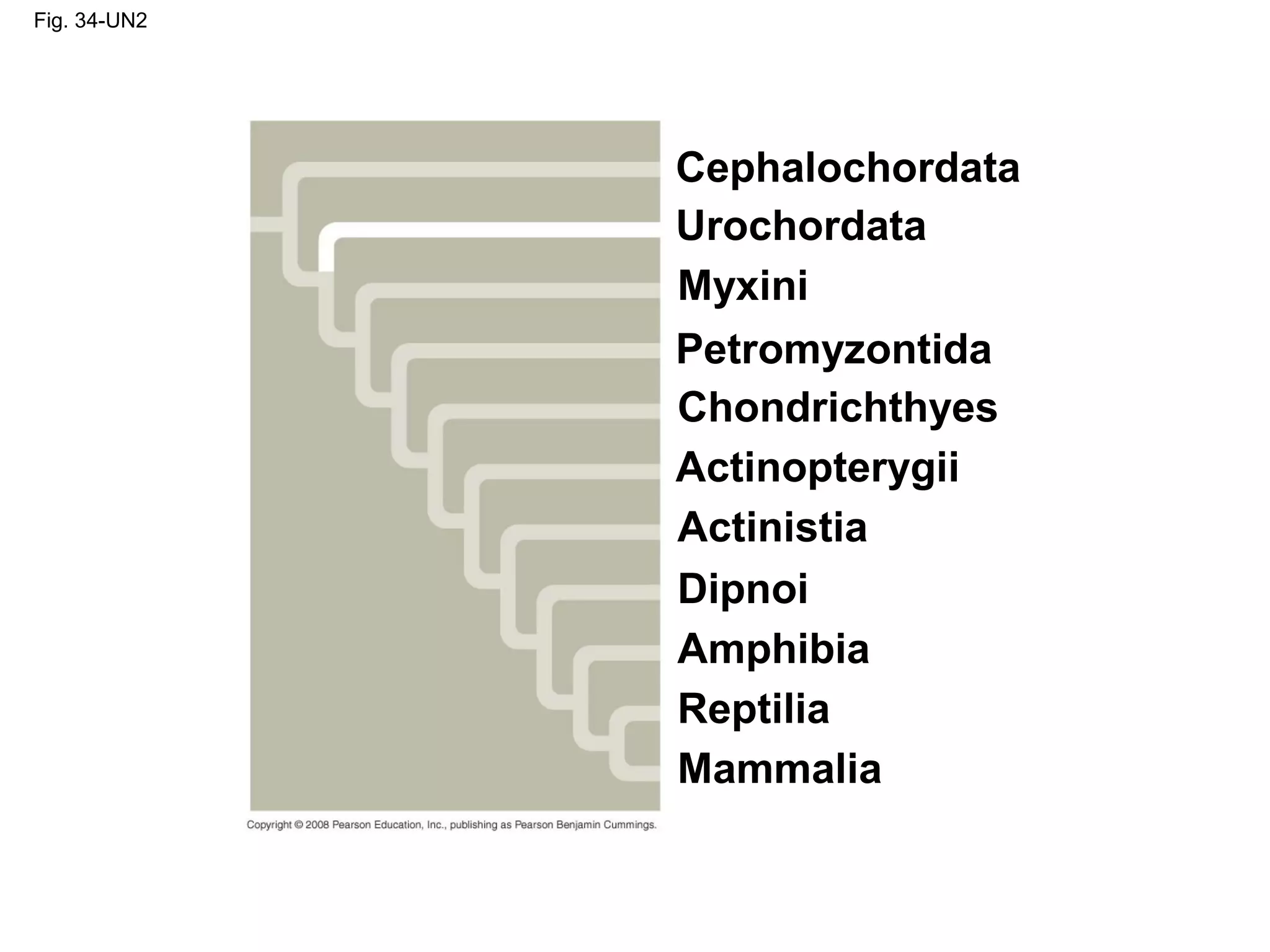

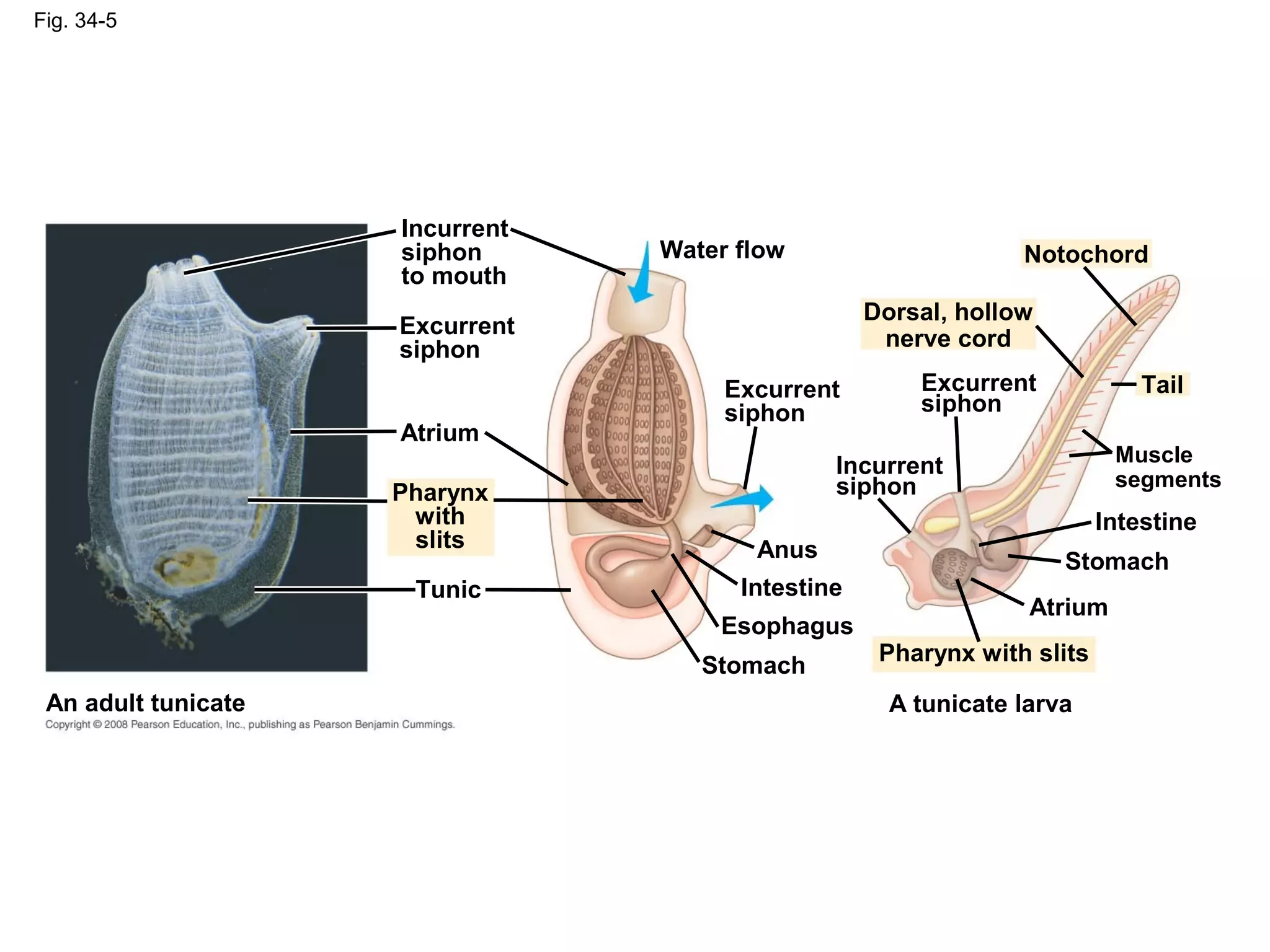

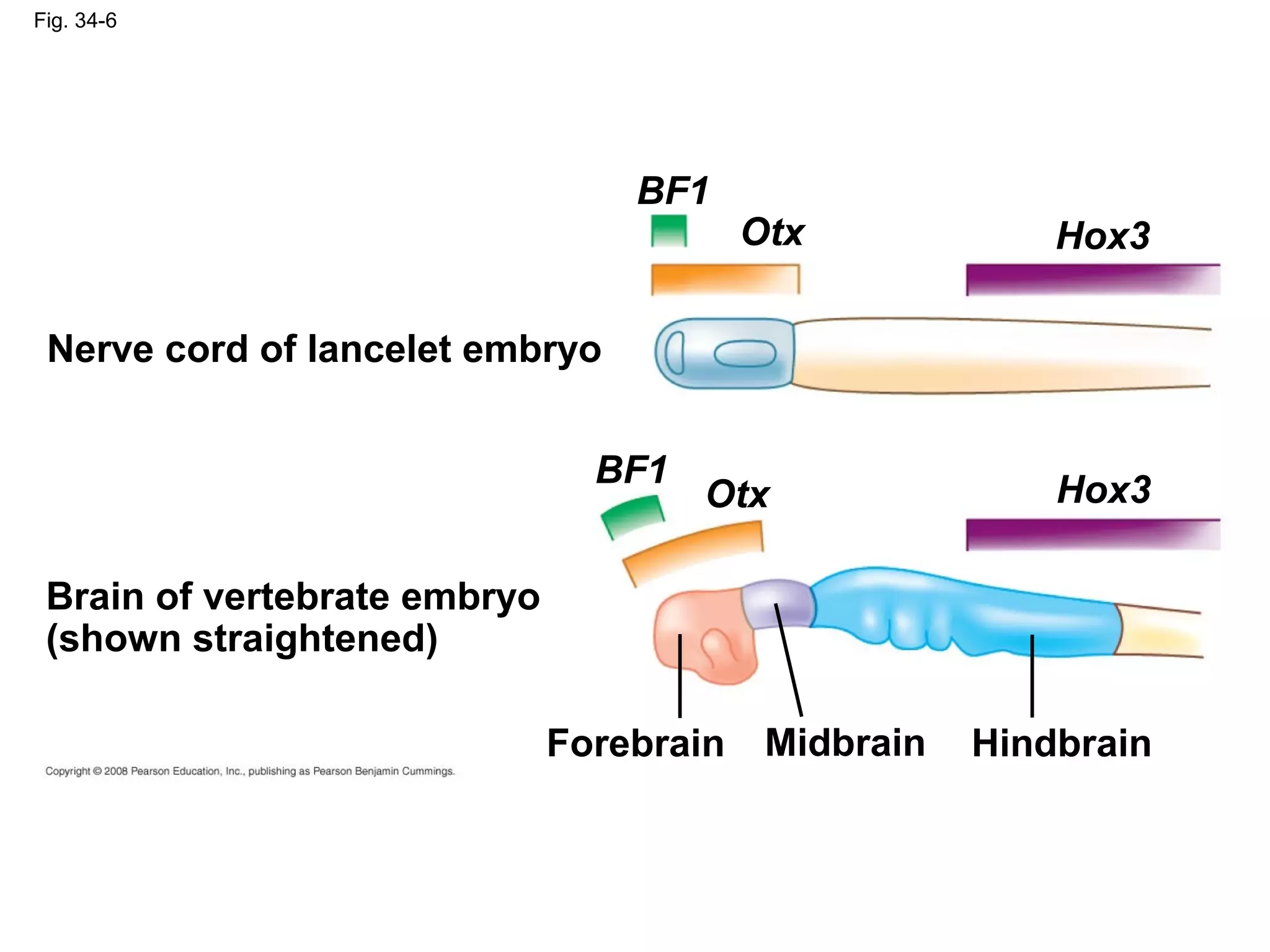

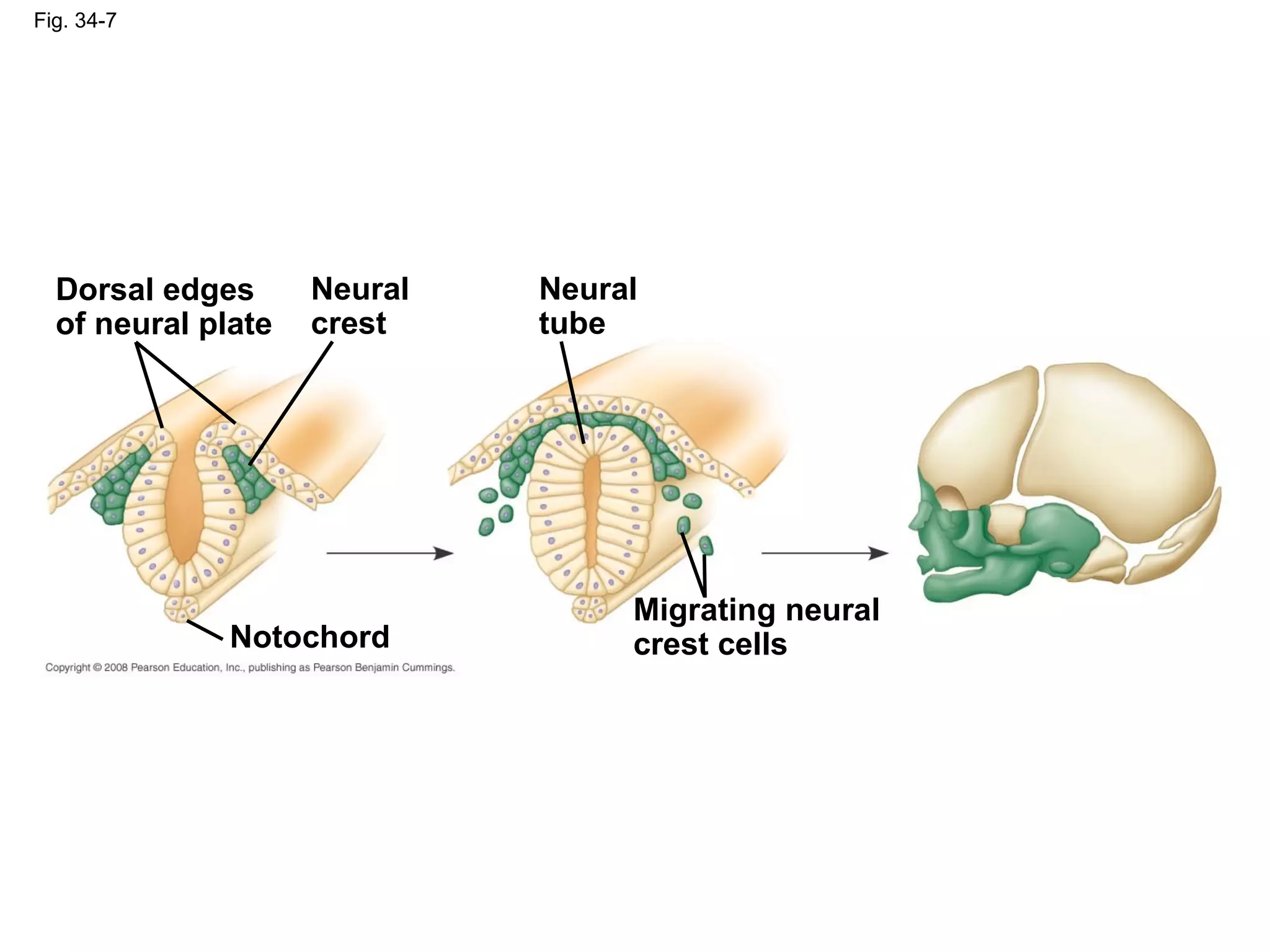

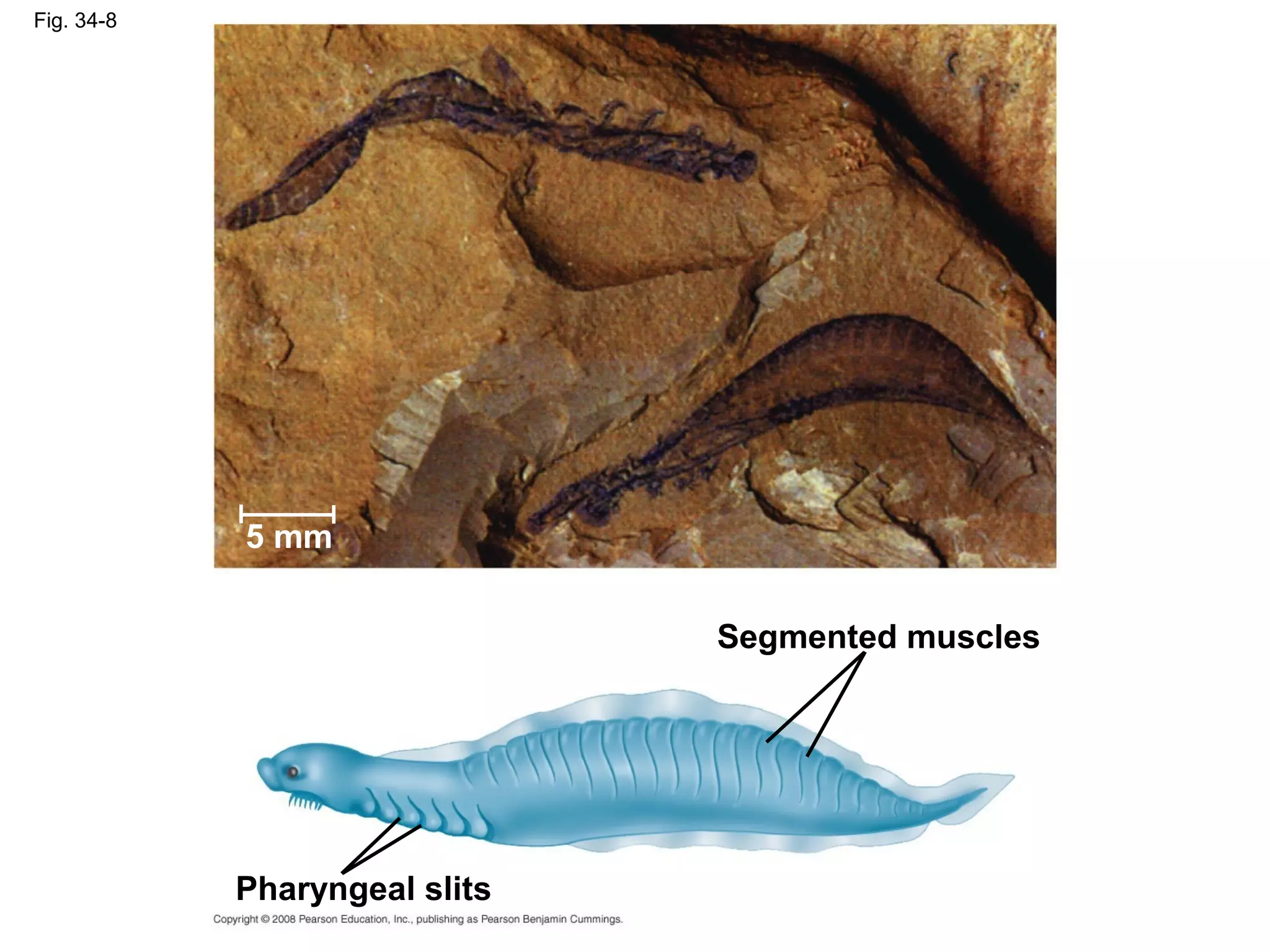

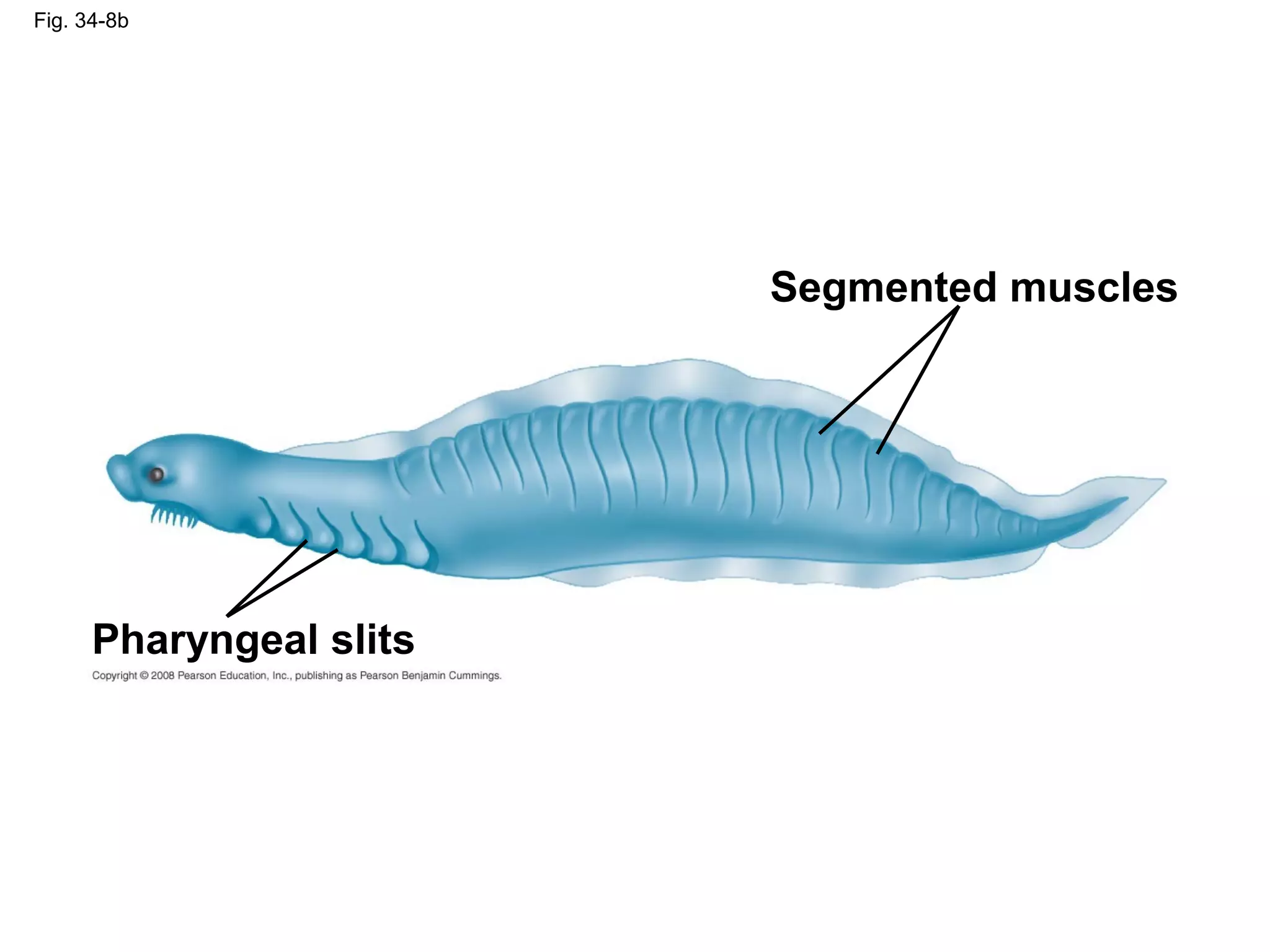

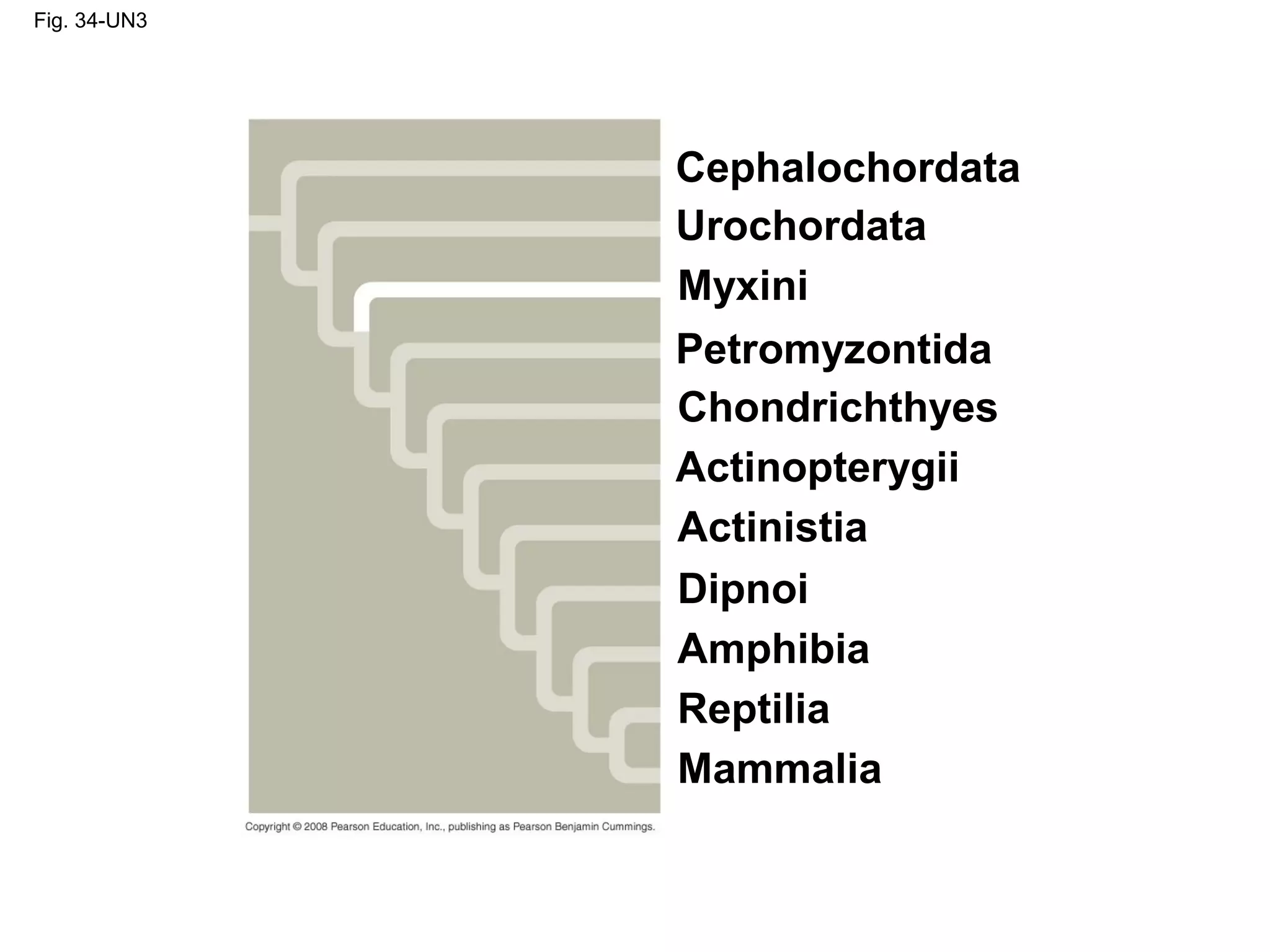

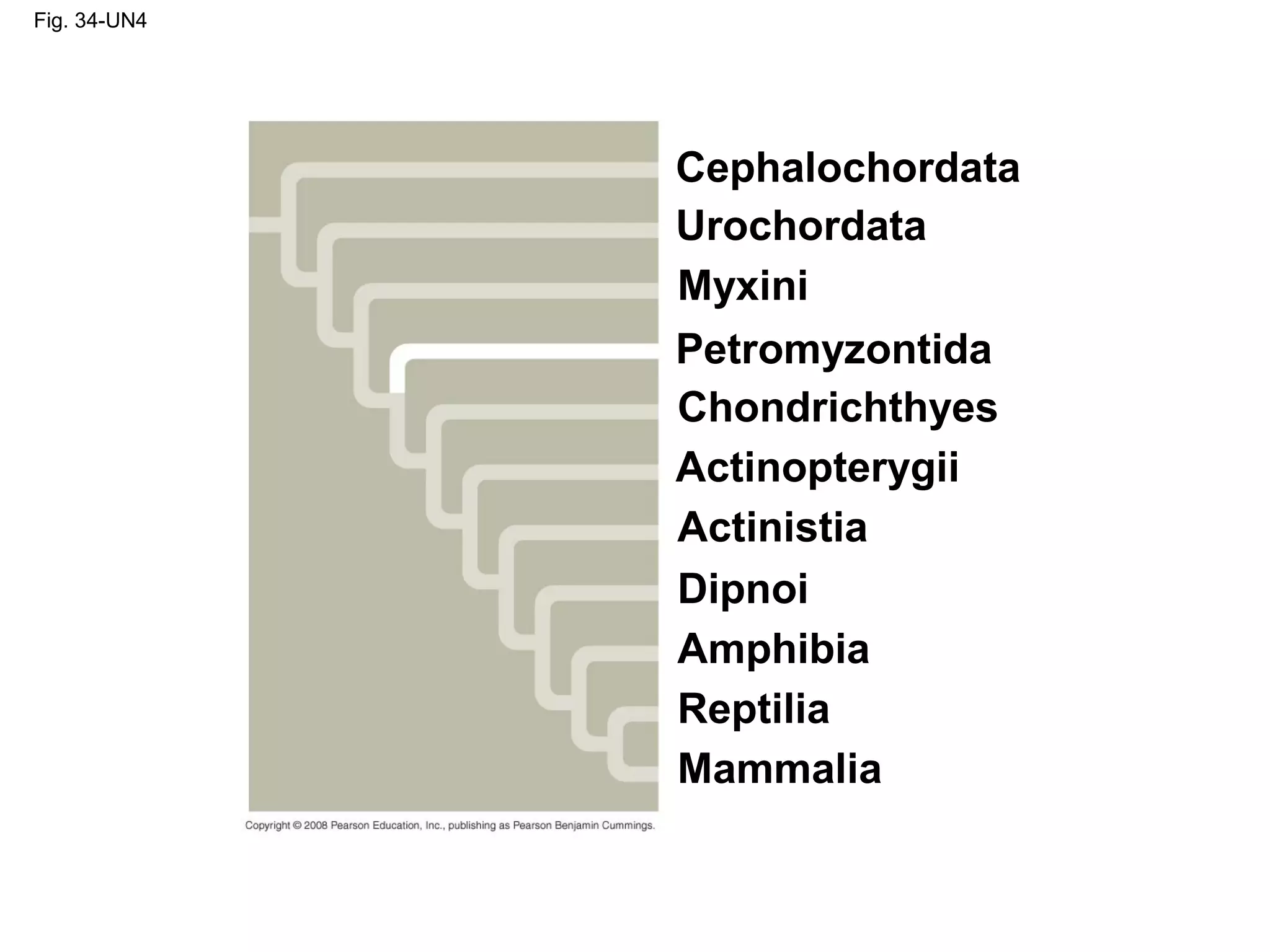

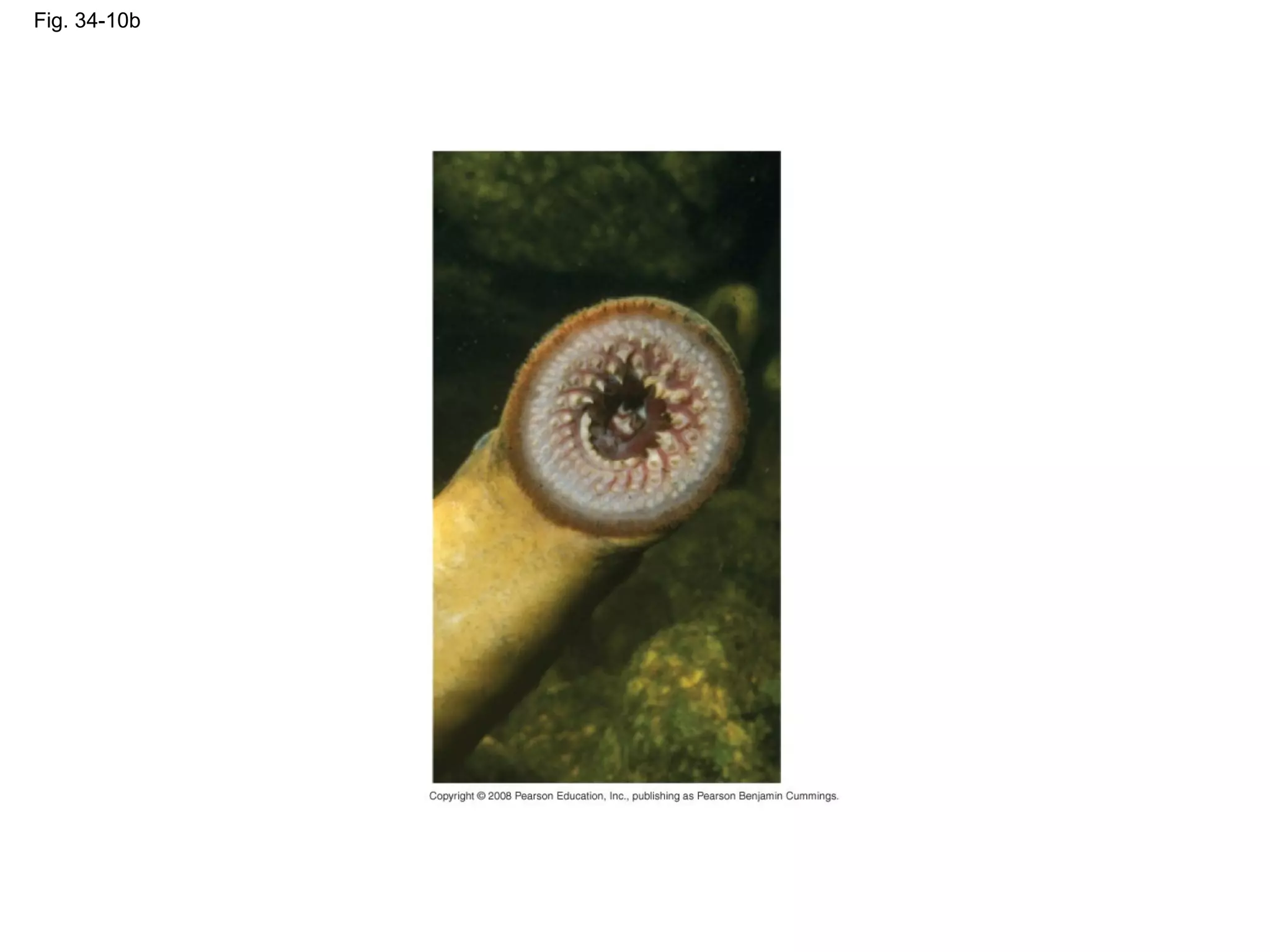

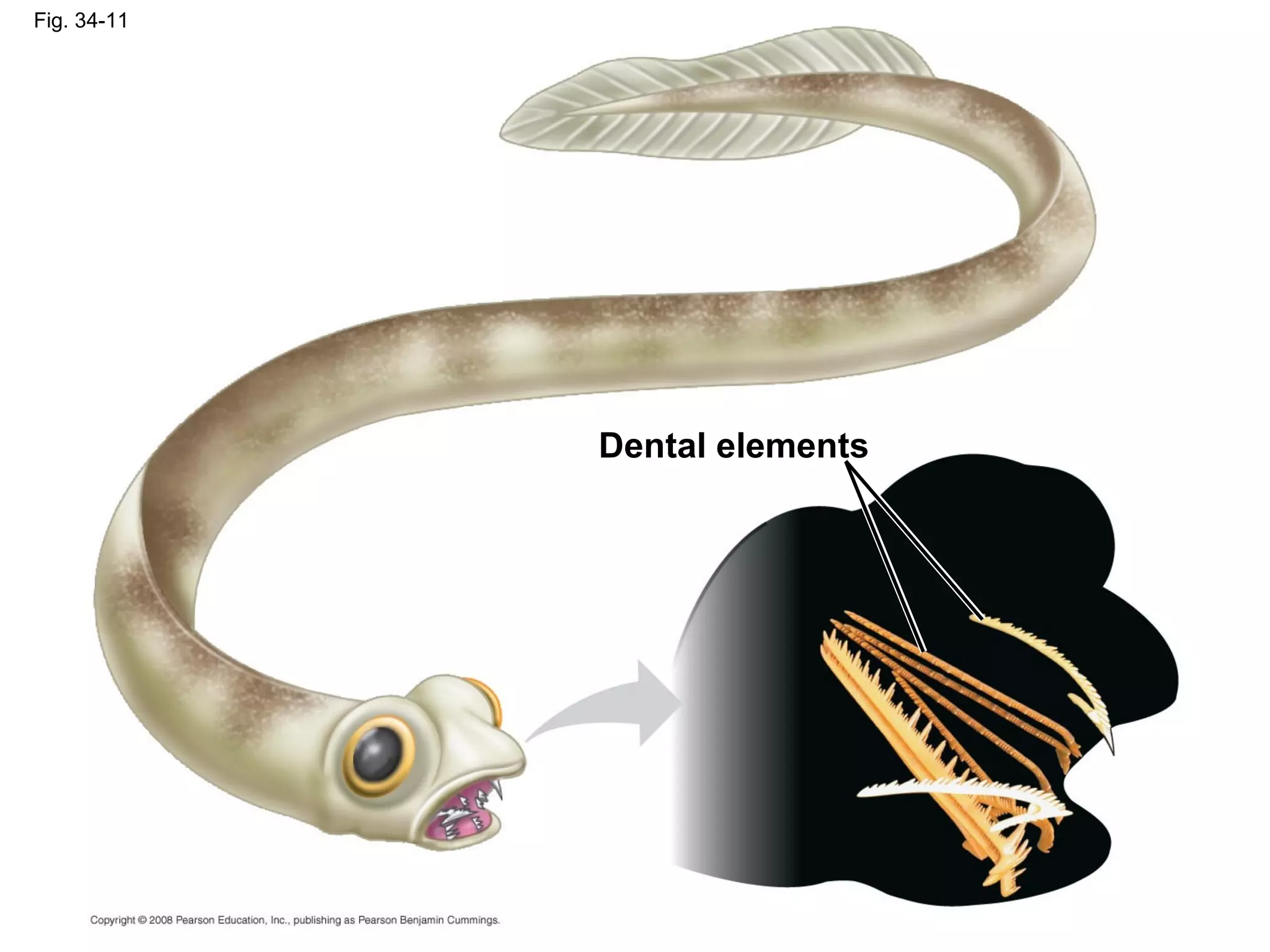

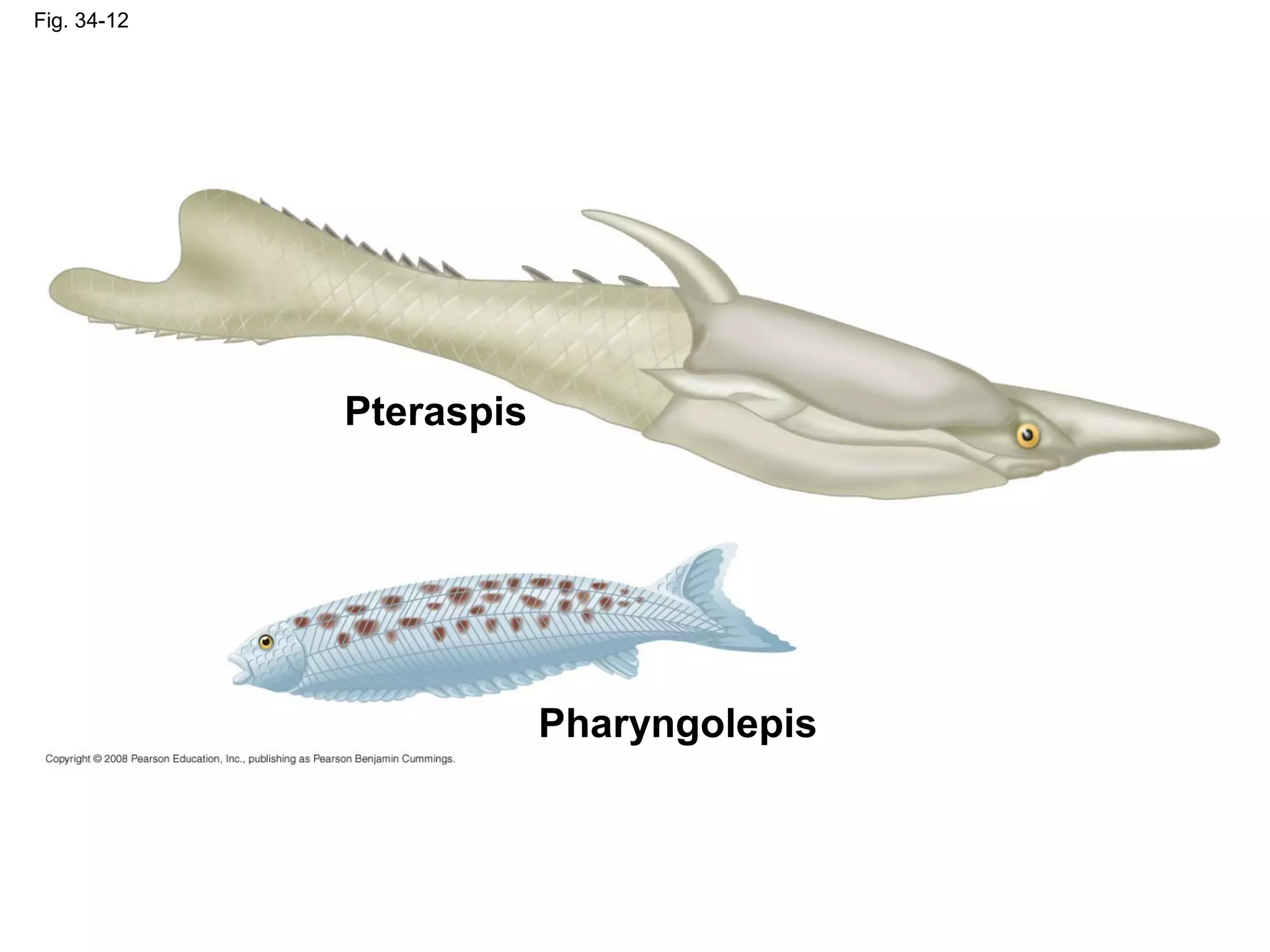

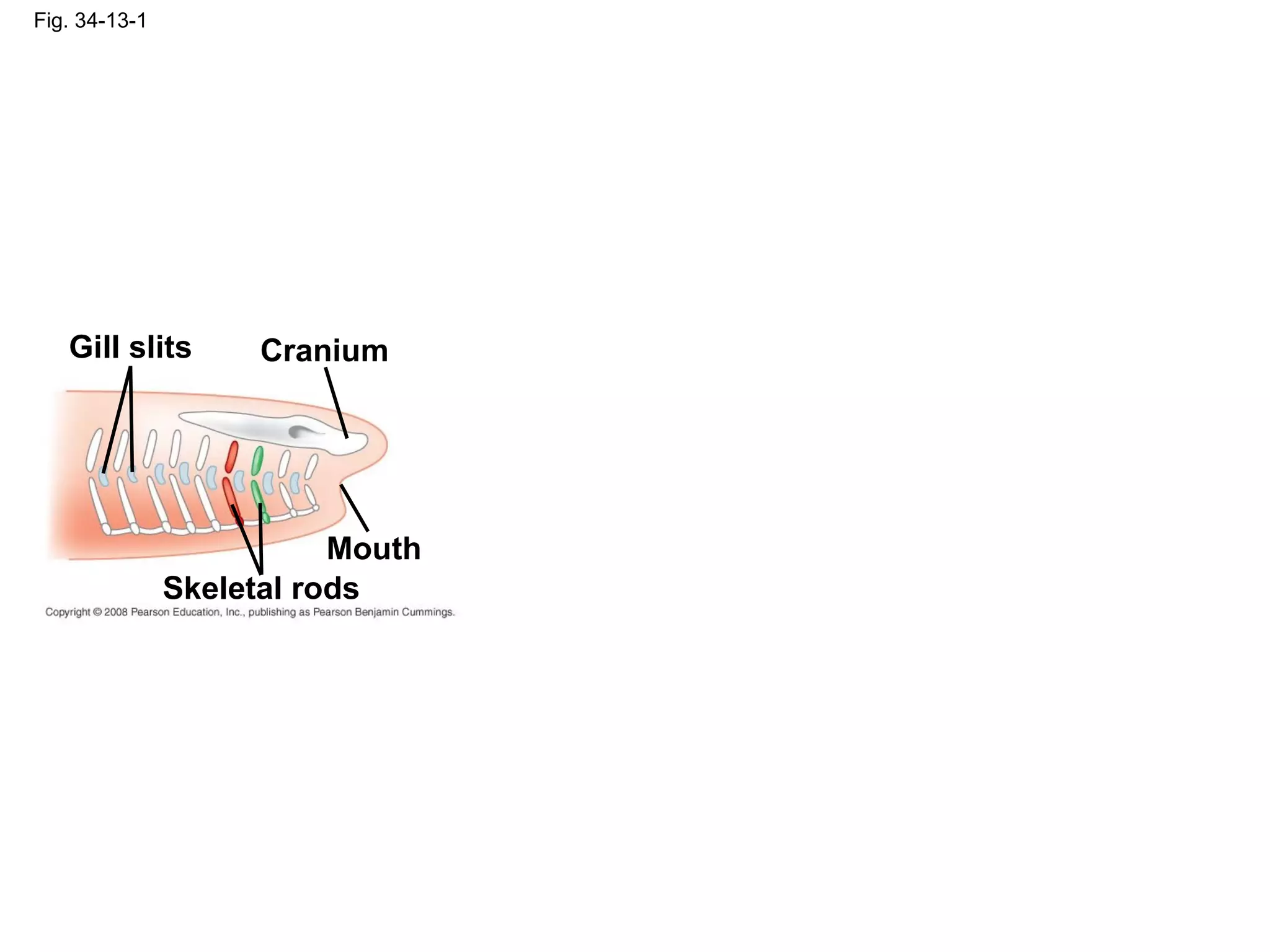

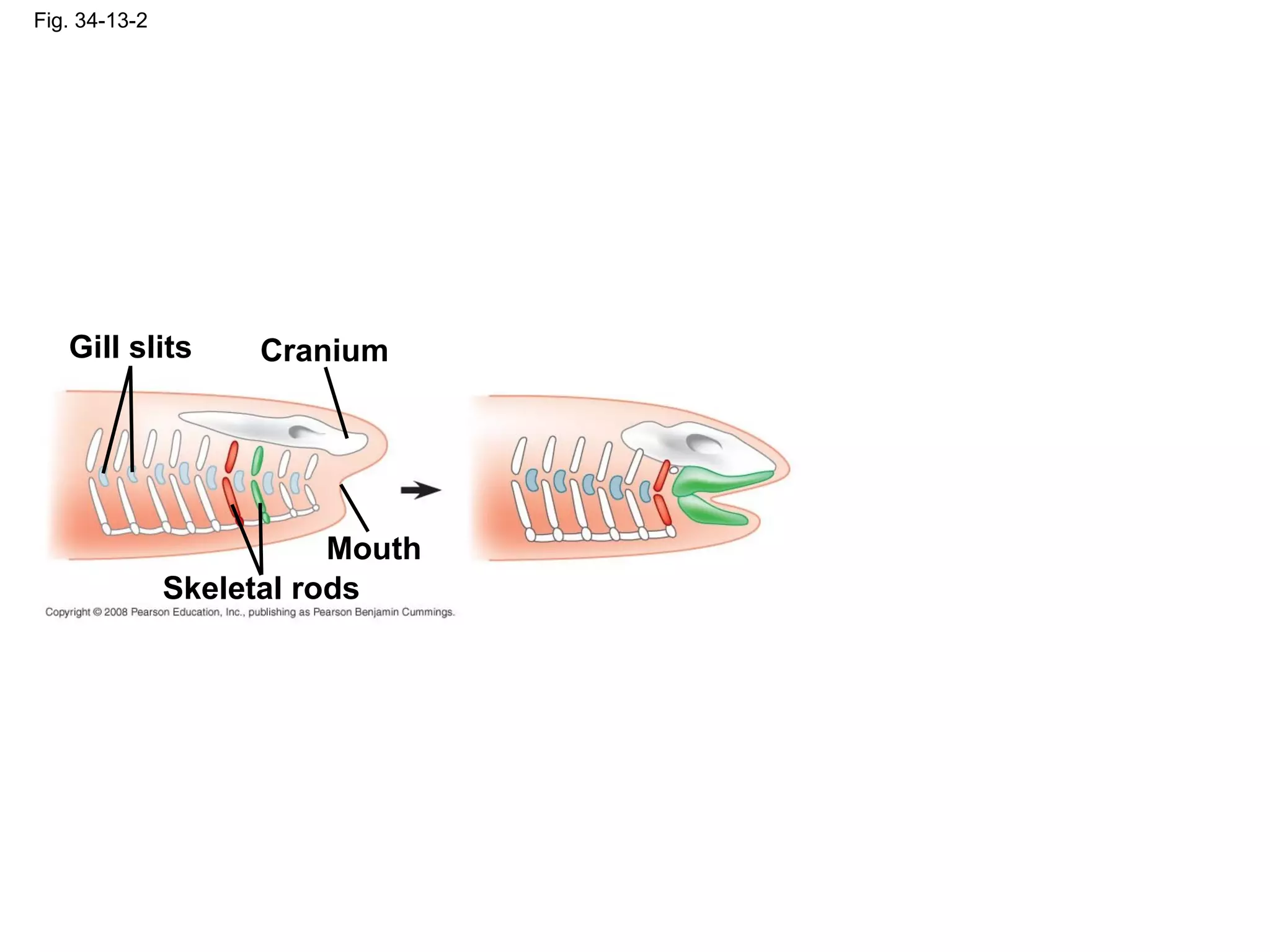

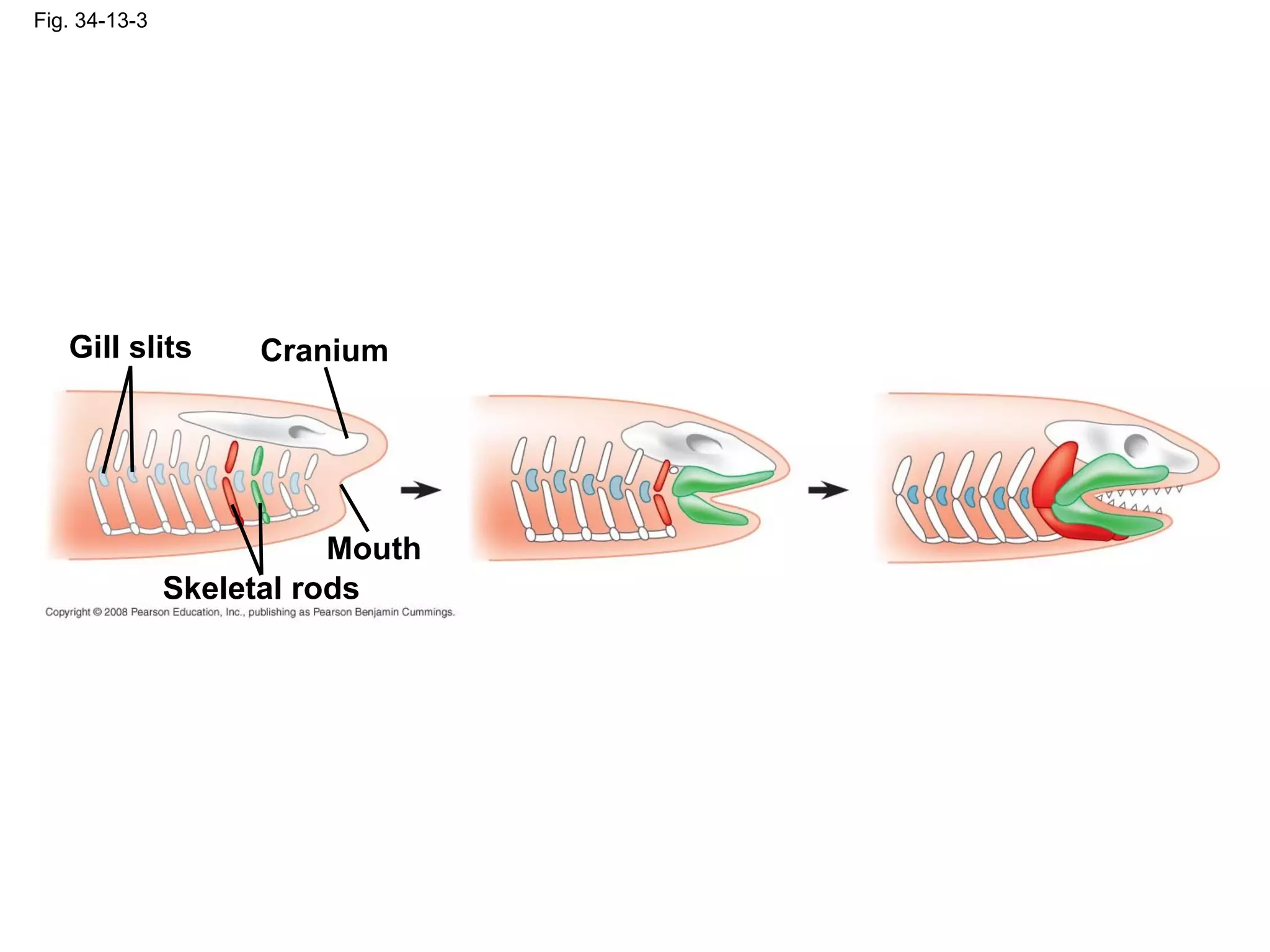

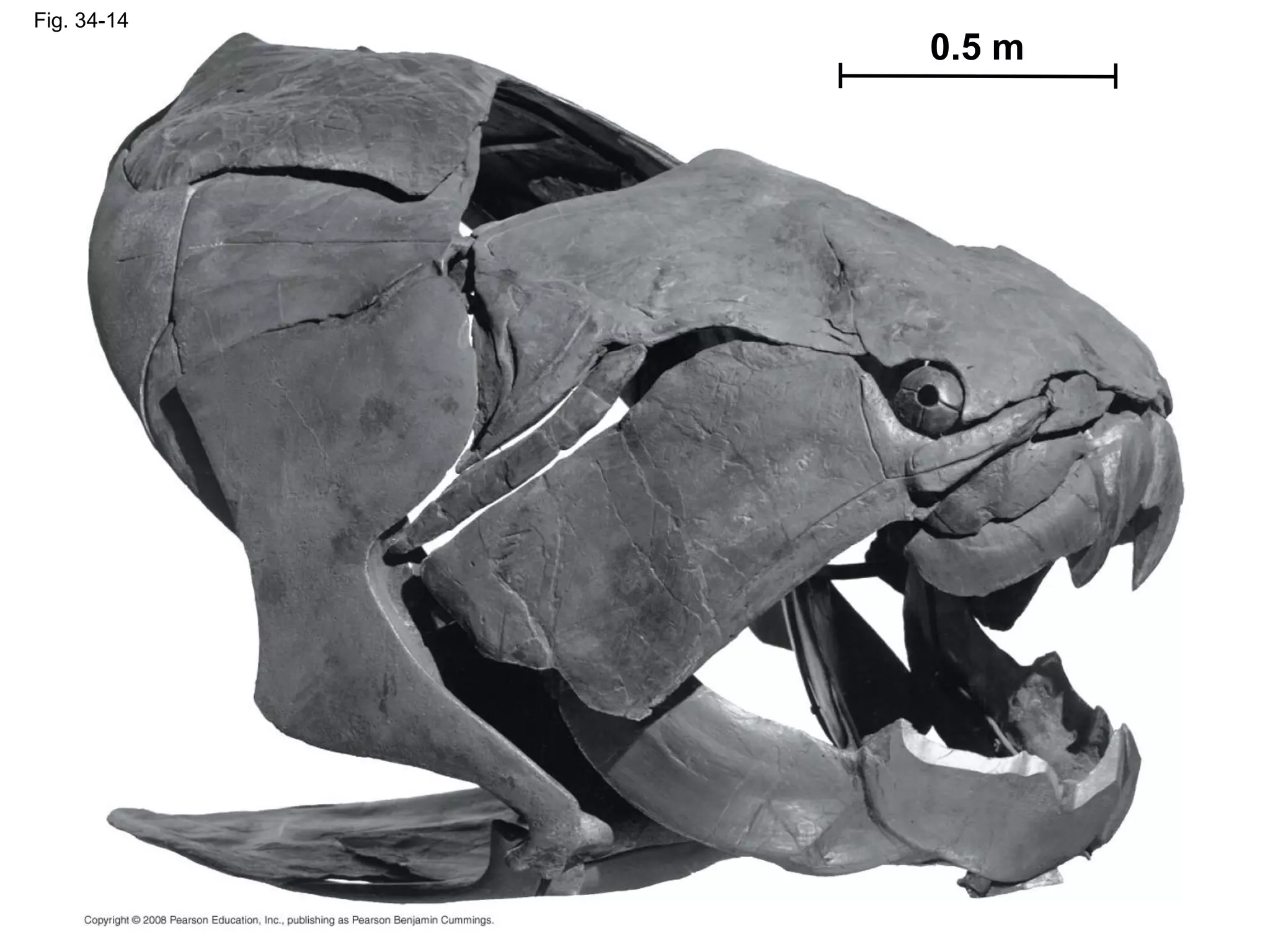

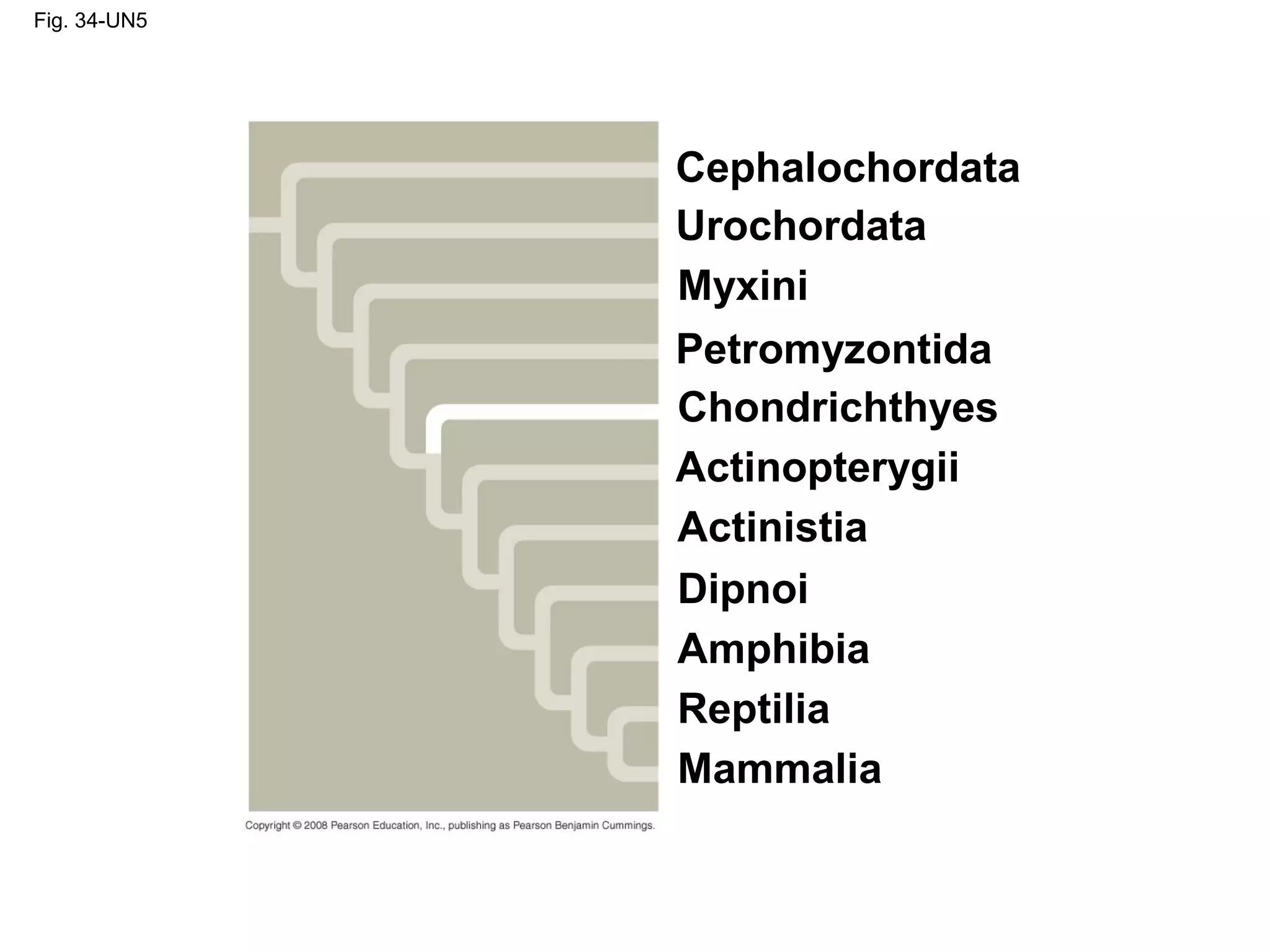

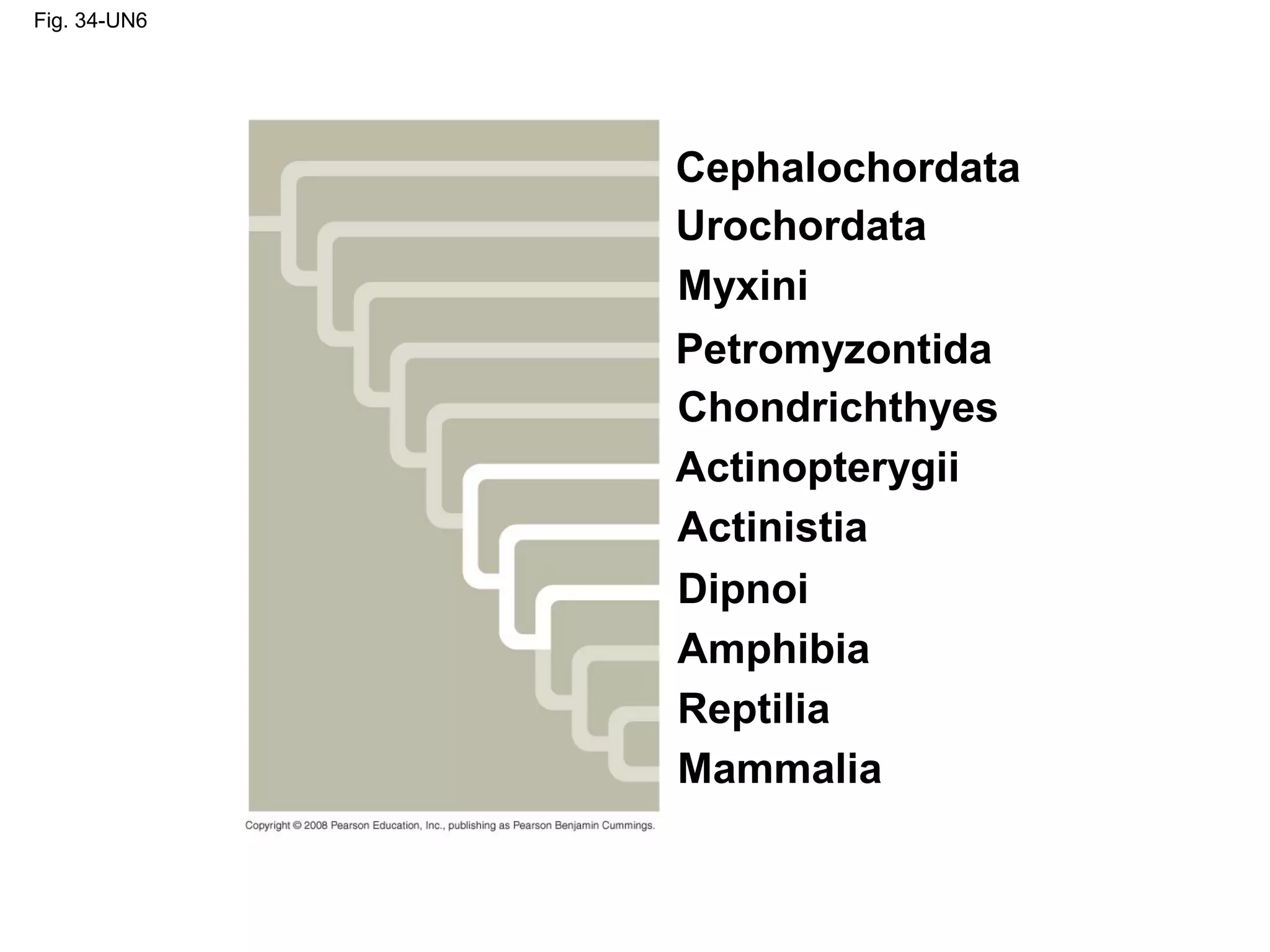

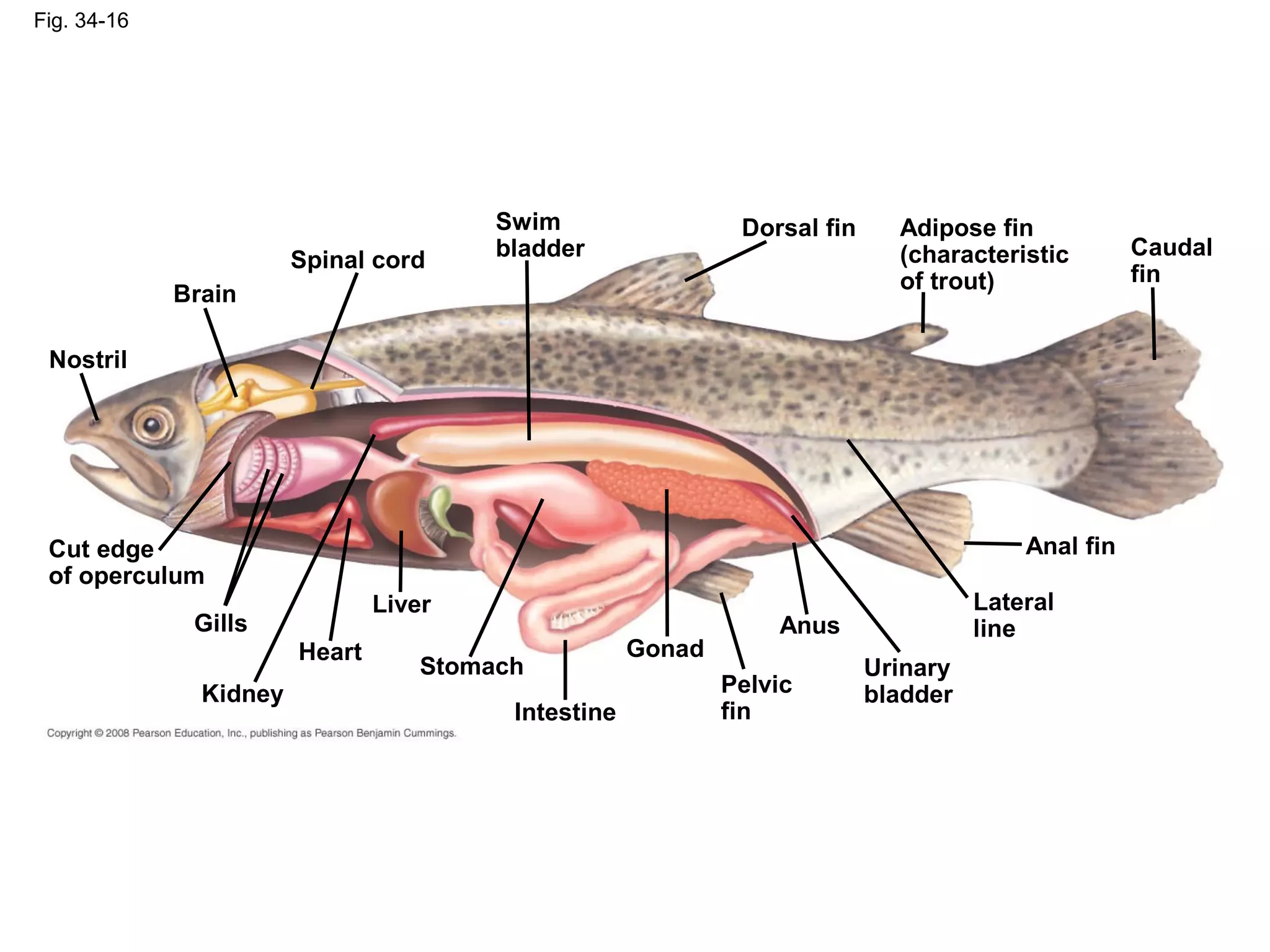

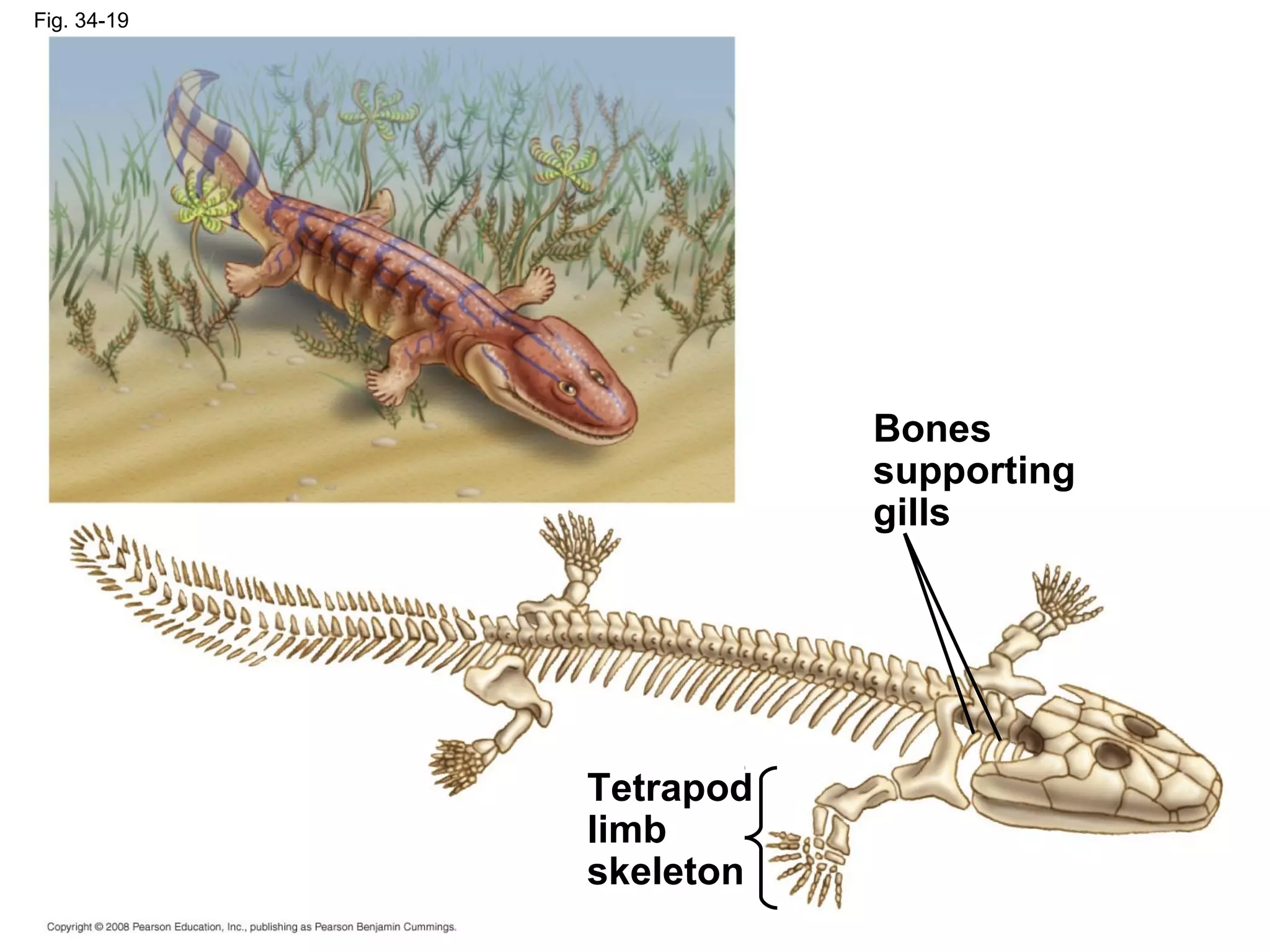

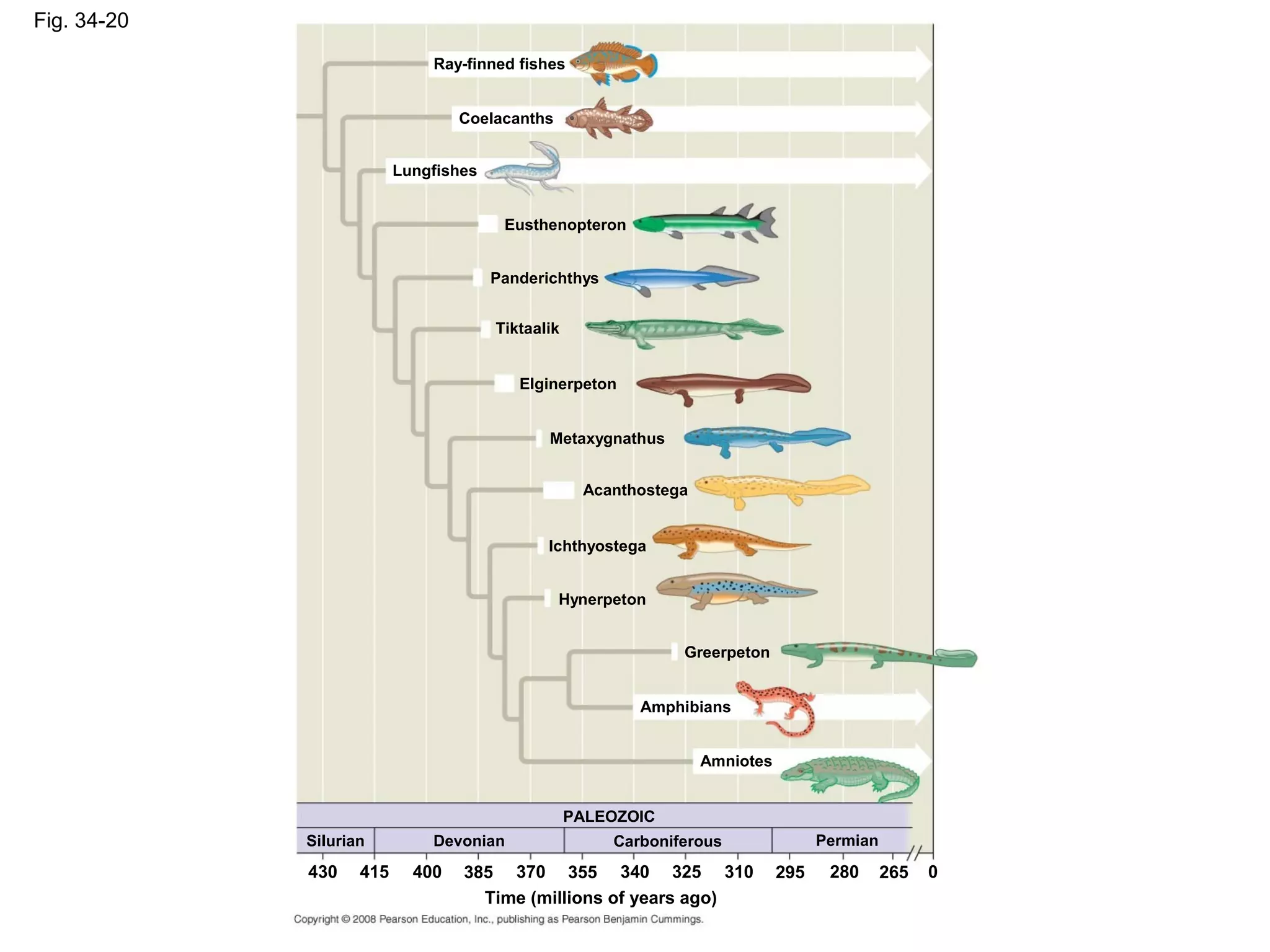

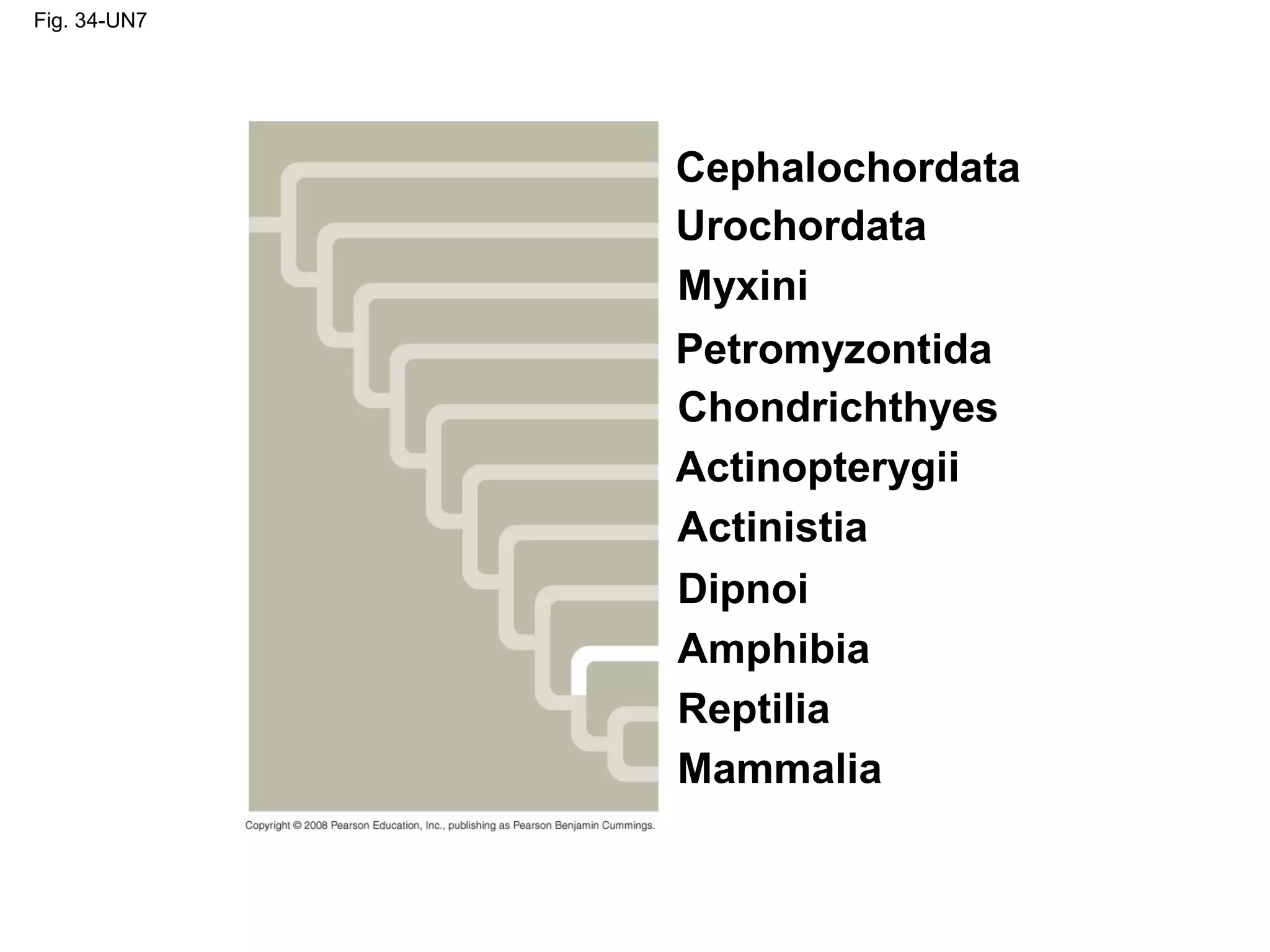

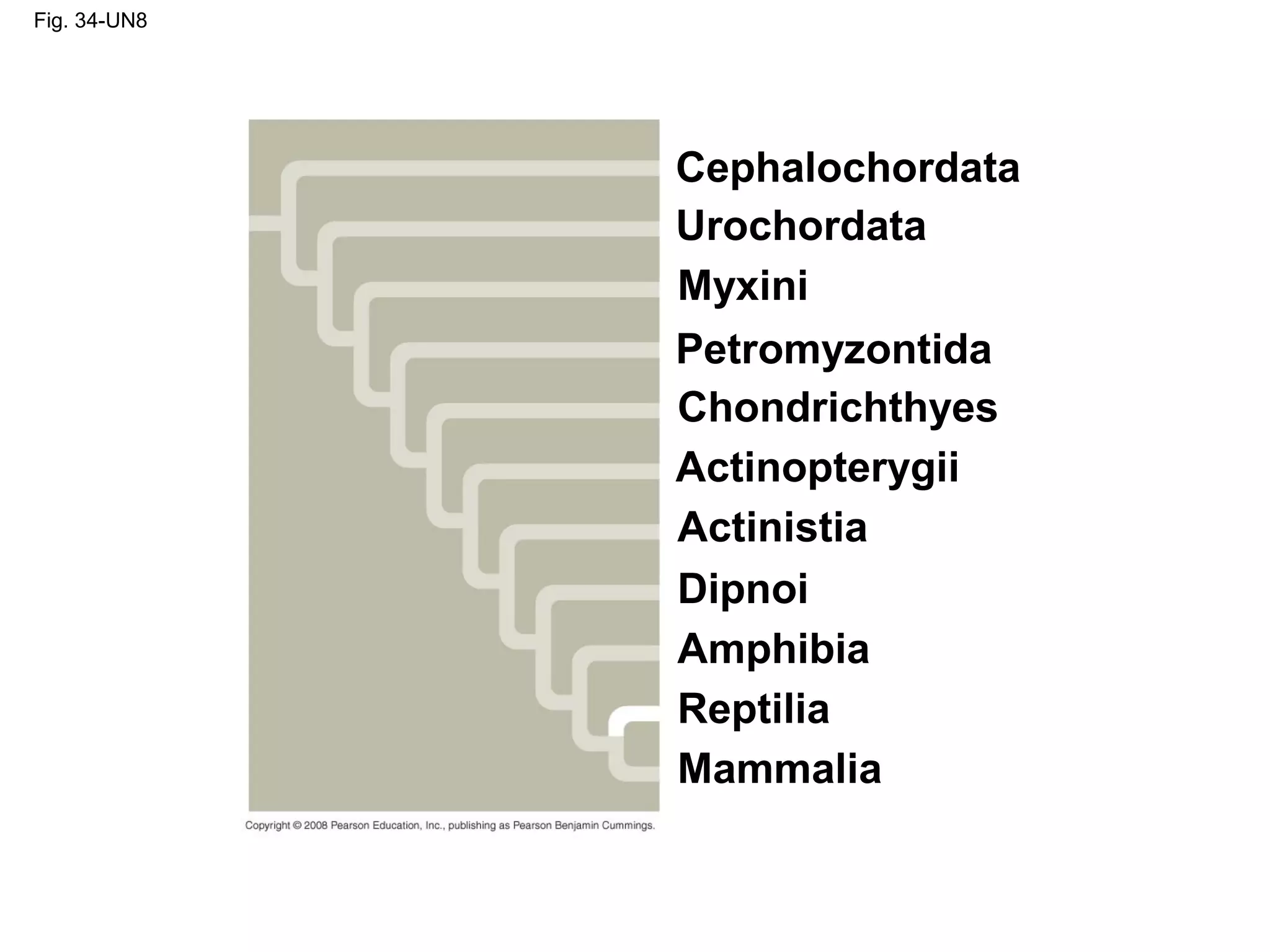

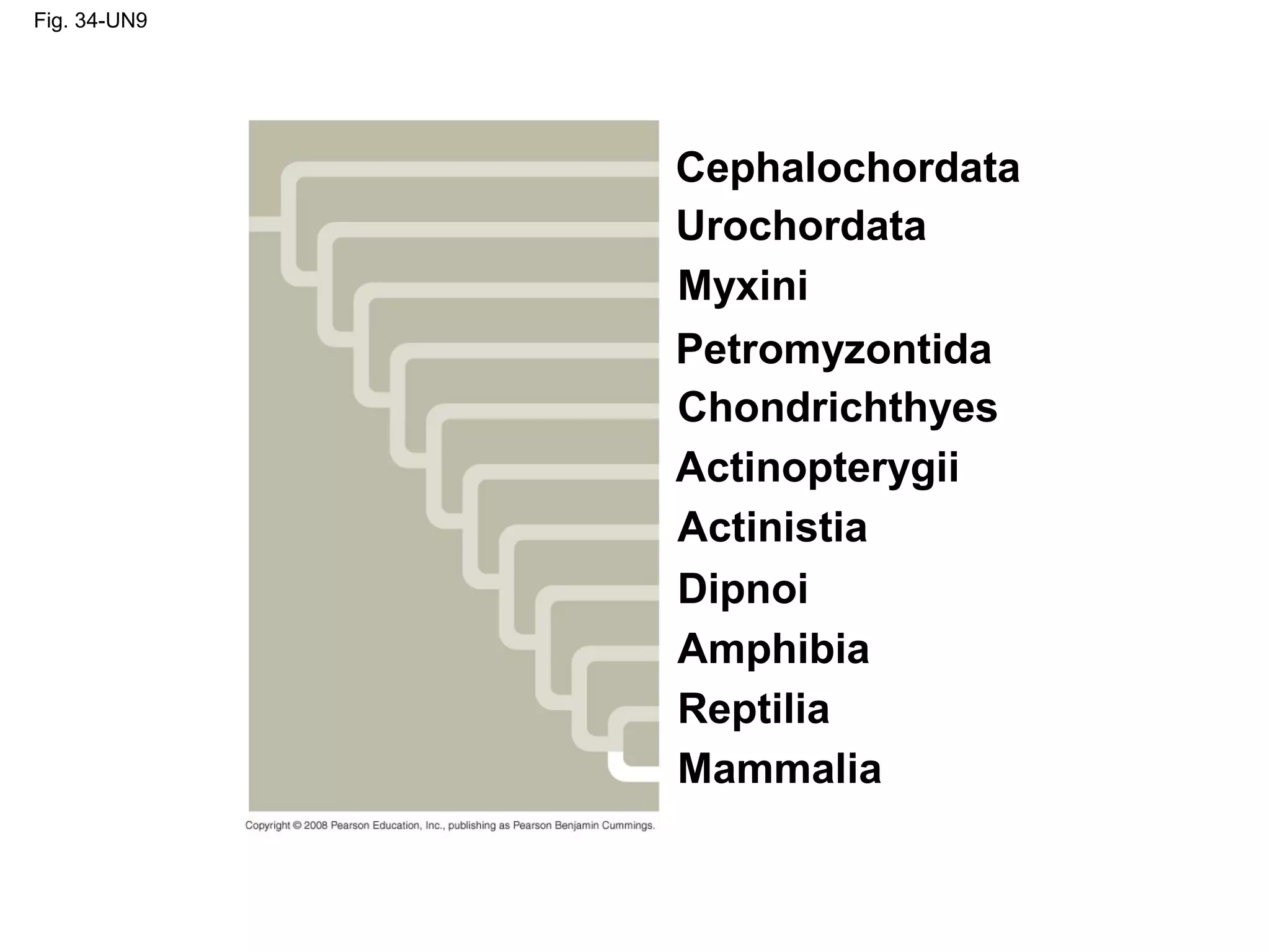

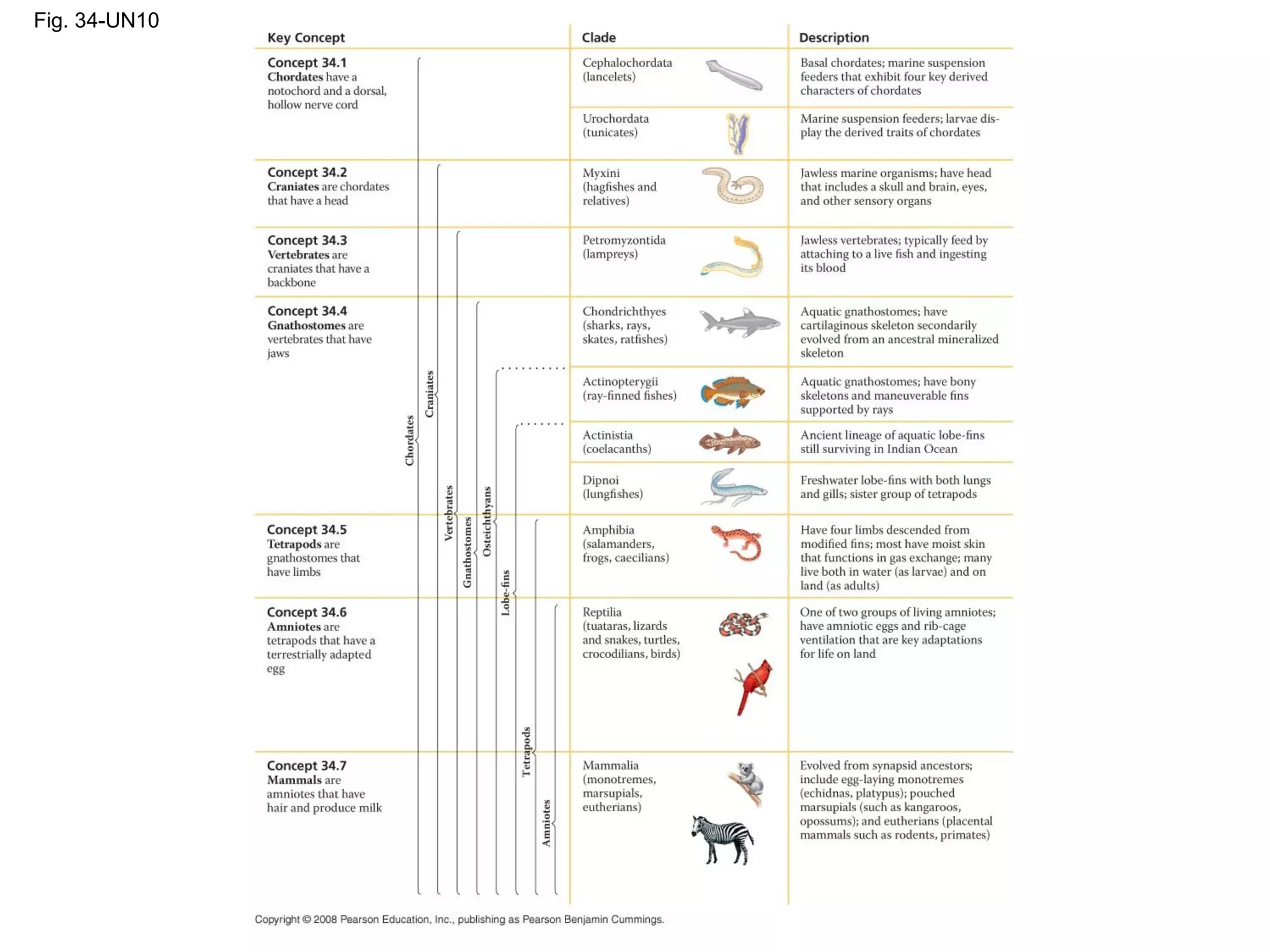

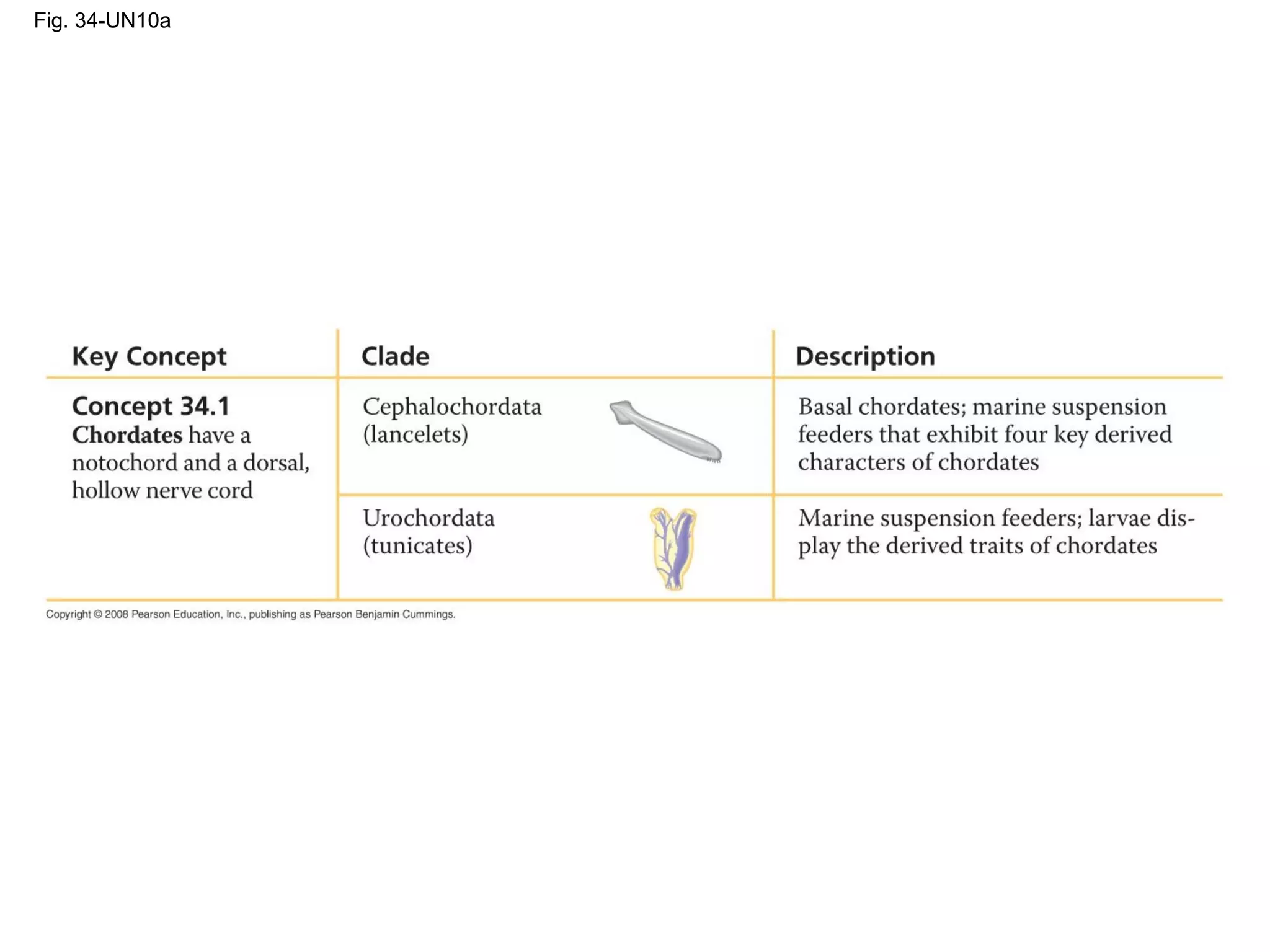

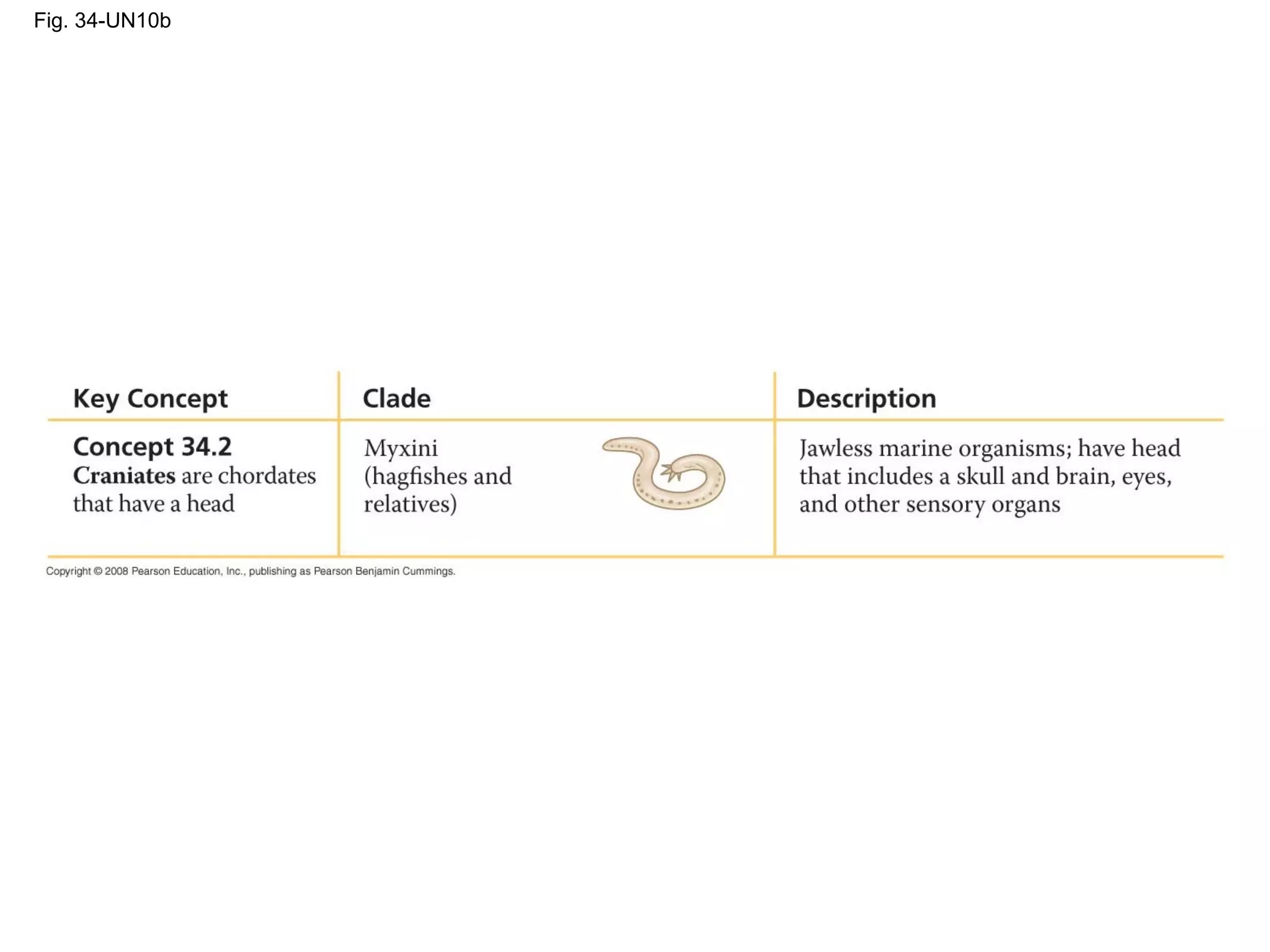

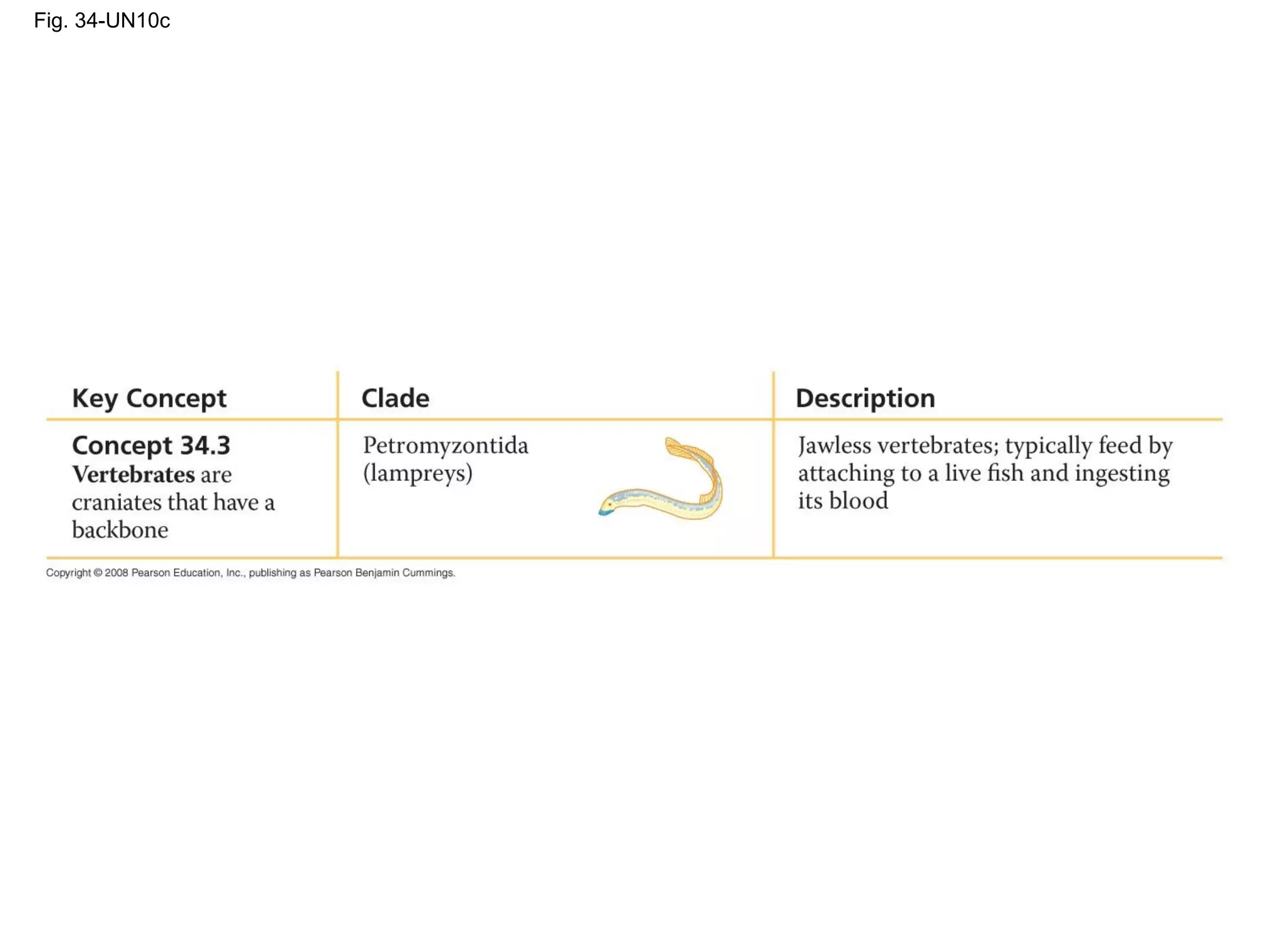

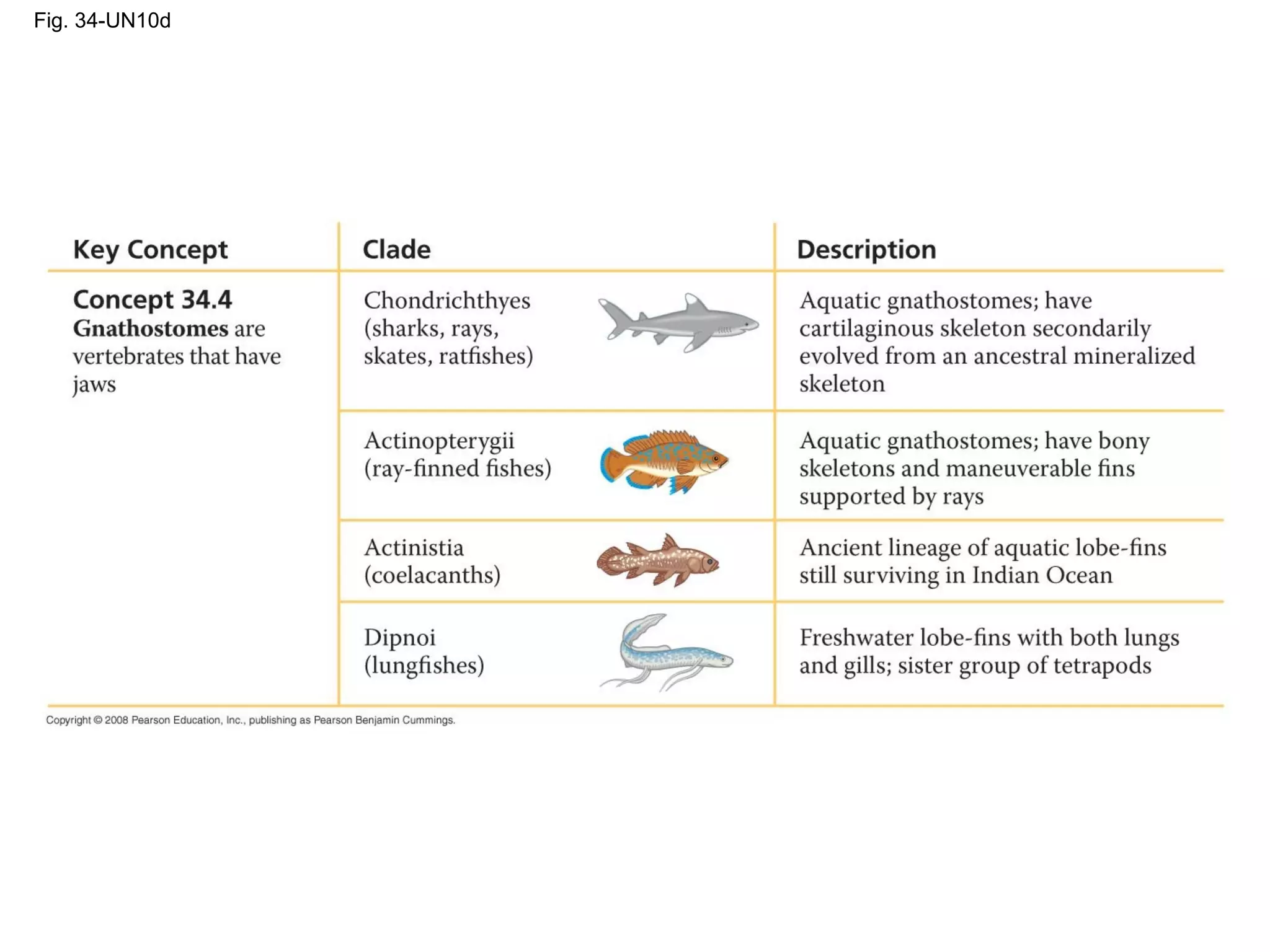

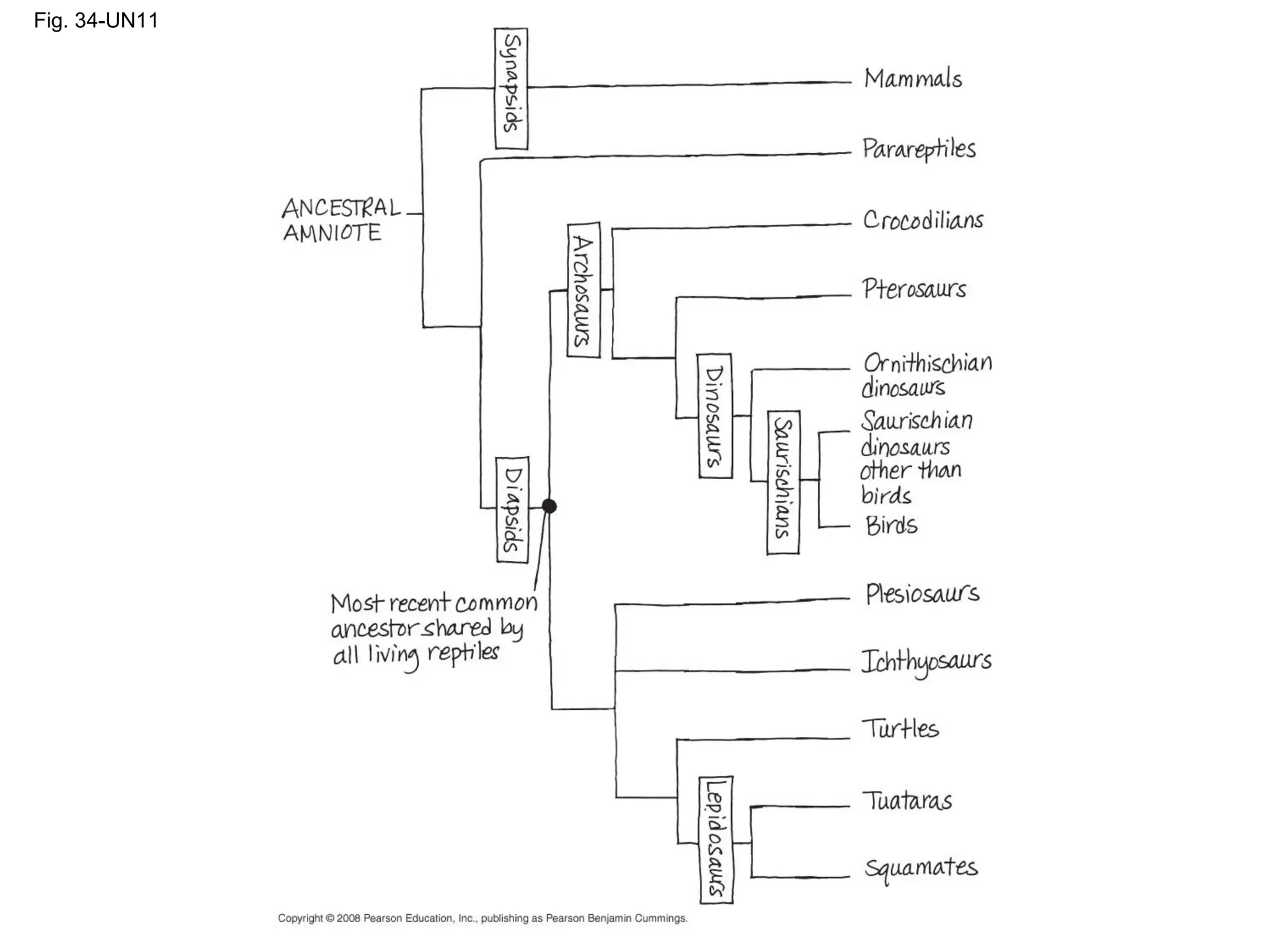

This document discusses the evolution of vertebrates from early chordates. It covers the key characteristics of chordates like having a notochord and dorsal nerve cord. Chordates evolved into craniates, which have a head. Craniates evolved traits like a skull, brain, and neural crest cells that give rise to bone and cartilage. Craniates also developed gill slits for respiration and had higher metabolisms. Vertebrates are a subphylum of craniates that have a backbone made of vertebrae, and include over 52,000 species ranging greatly in form.