1. The document discusses the concepts of Euler's equation, Bernoulli's equation, and their applications in fluid dynamics problems involving one-dimensional steady flow.

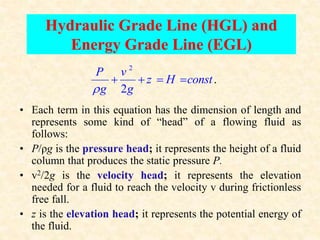

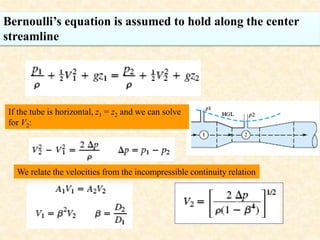

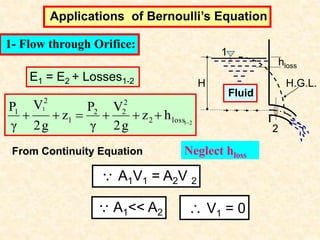

2. Bernoulli's equation relates the total pressure, velocity, and elevation along a streamline. It is used to analyze flow through orifices, venturi meters, and orifice meters.

3. Measurement techniques like the pitot-static tube and manometers are used to experimentally determine velocities and pressure losses based on the equations.