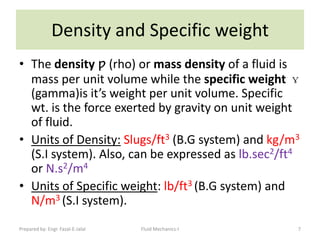

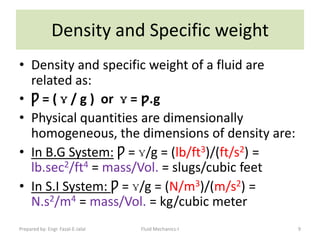

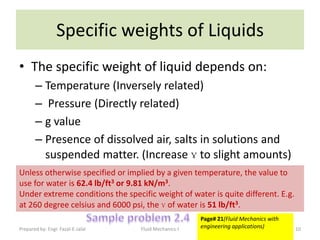

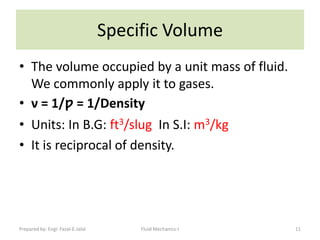

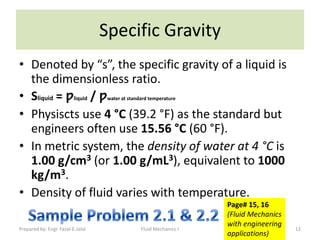

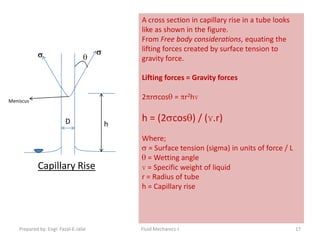

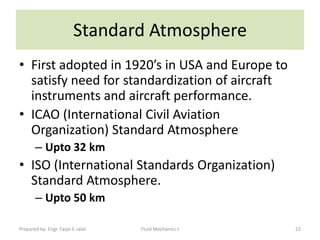

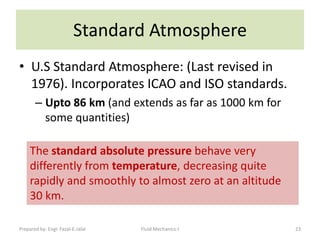

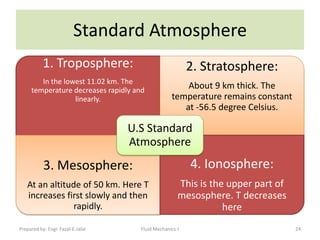

The document discusses key physical properties of fluids including density, specific weight, specific volume, specific gravity, and surface tension. It defines density as mass per unit volume and specific weight as weight per unit volume. Specific volume is the reciprocal of density. Specific gravity is the ratio of a liquid's density to that of water. Surface tension is the property of liquids that allows them to resist tensile stresses and makes liquids rise in thin tubes. Capillary rise is caused by surface tension and adhesion. The document also discusses vapor pressure, standard atmospheres, and other fluid properties.