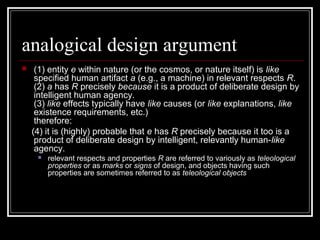

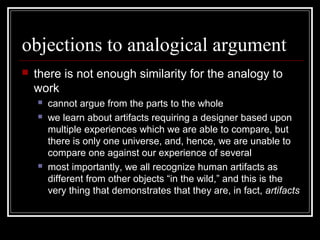

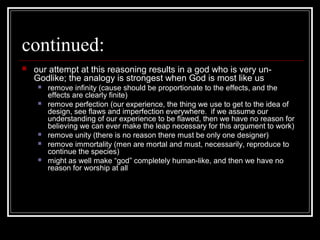

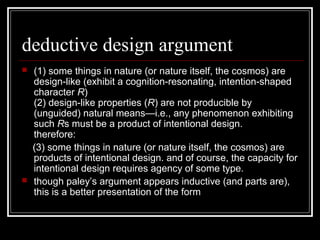

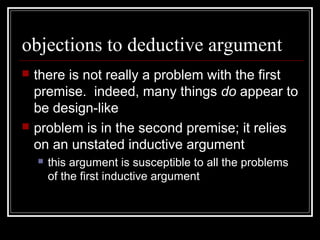

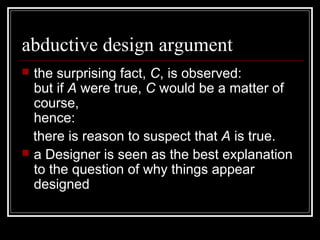

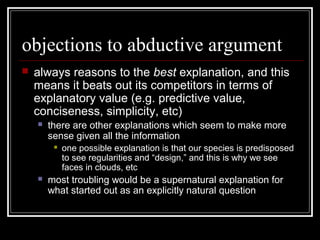

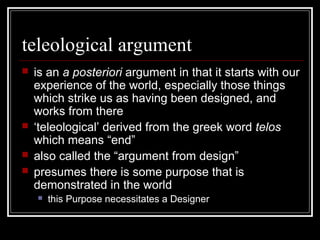

The teleological argument, also known as the argument from design, argues that certain features of the natural world appear designed and are best explained by an intelligent designer. There are three main forms this argument takes: analogical, deductive, and abductive. The analogical form argues from similarities between natural objects and human artifacts. The deductive form argues that design-like properties could not arise without an intentional designer. The abductive form argues that a designer is the best explanation for why things appear designed. However, each form is subject to objections regarding analogies, reliance on inductive arguments, and alternative natural explanations.

![design inference patterns

[Q] p. 87, first statement by cleanthes

articulates the basic idea

there are a variety of different forms the

argument can take

analogical design arguments

deductive design arguments

abductive design arguments](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/129-3699/85/1-29-3-320.jpg)