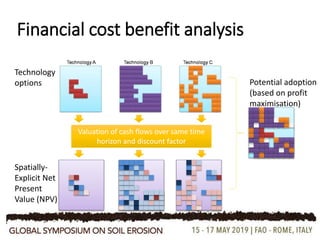

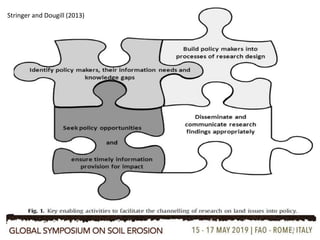

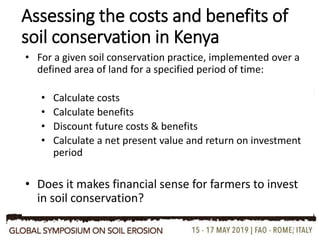

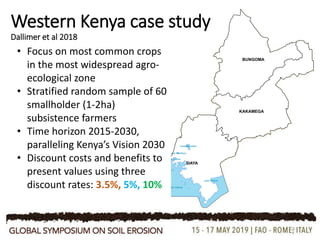

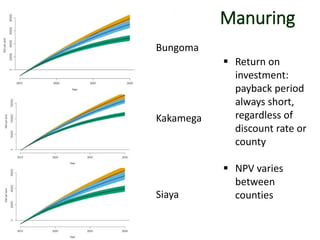

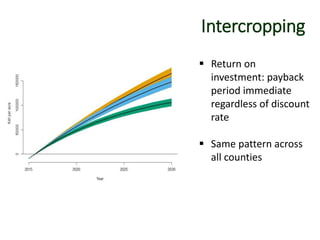

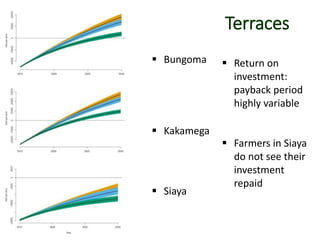

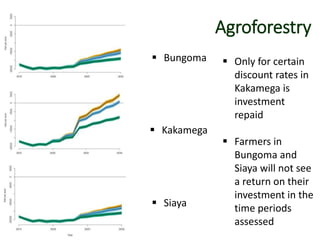

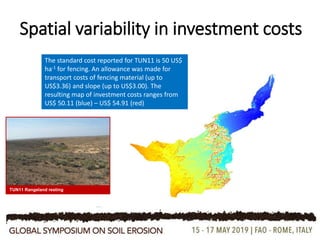

The document discusses the economic assessment of soil erosion and its management, emphasizing the importance of valuing soil ecosystem services and understanding the costs and benefits associated with soil conservation practices. It highlights the need for policies that recognize both individual farmer and societal gains while addressing externalities that are often overlooked in market prices. The case study in Kenya indicates variability in return on investment for different soil conservation practices and calls for targeted policy to support cost-effective soil management solutions.

![[A – B – C + D] =

Annual cash flow series for

each technology and grid cell

Production

foregone

without case

X Value (€)

X Value (€)

Foregone

costs of:

- Production

Costs of:

- Production

- Maintenance

- Other (e.g.

area loss)

DC

BAProduction

with applied

technology

Cash flow series are constructed for

each grid cell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4gserstringerforromeclean-190524125905/85/Addressing-soil-erosion-through-policy-and-economic-assessments-16-320.jpg)