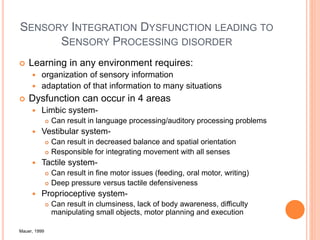

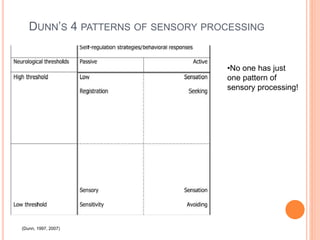

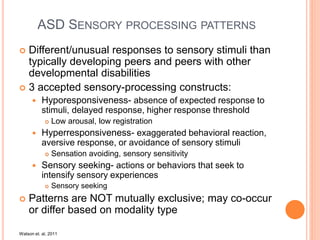

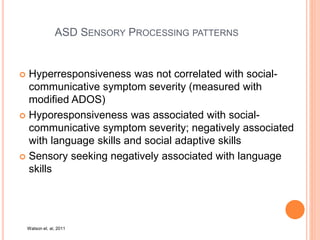

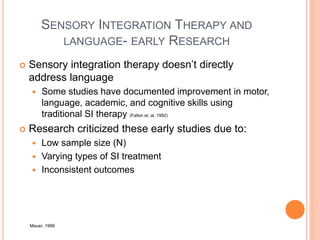

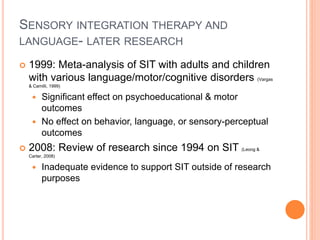

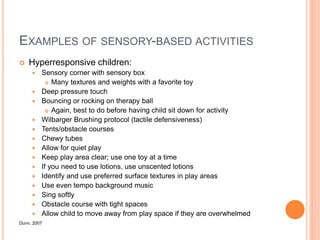

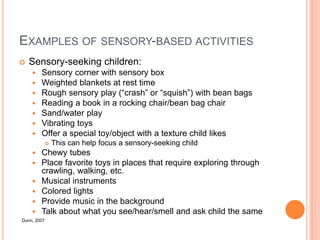

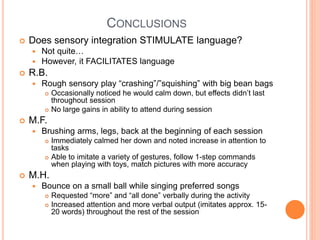

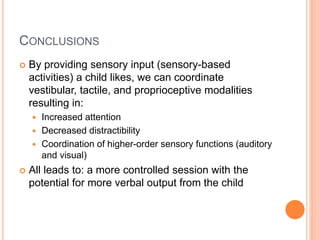

This document discusses sensory processing in children and whether sensory integration techniques support language development. It defines sensory integration and outlines various sensory processing patterns seen in children, including those with autism spectrum disorder. While early research showed improvements in language and other skills from sensory integration therapy, later meta-analyses found no effects on language outcomes. However, incorporating sensory-based activities into therapy sessions can help children organize their sensory systems and facilitate increased attention, which may support language production and comprehension. Examples of sensory-based activities are provided for different sensory processing profiles.