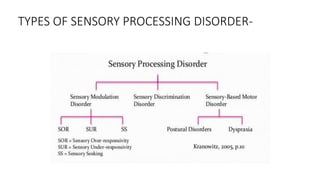

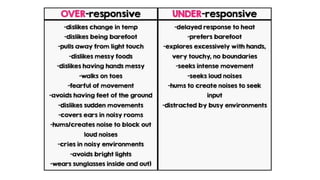

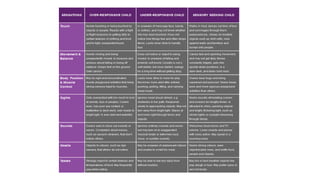

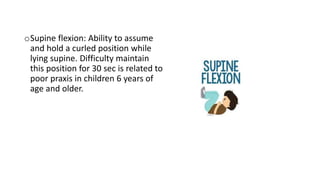

The document discusses sensory processing disorder (SPD), which is a condition that affects how the brain processes sensory information, potentially leading to abnormal behavior. It covers the history, definitions, causes, prevalence, various types of SPD, and its implications, emphasizing the role of occupational therapy in assessment and intervention. The document highlights the importance of understanding sensory integration and outlines the occupational therapy assessment tools and interventions used to support individuals with SPD.