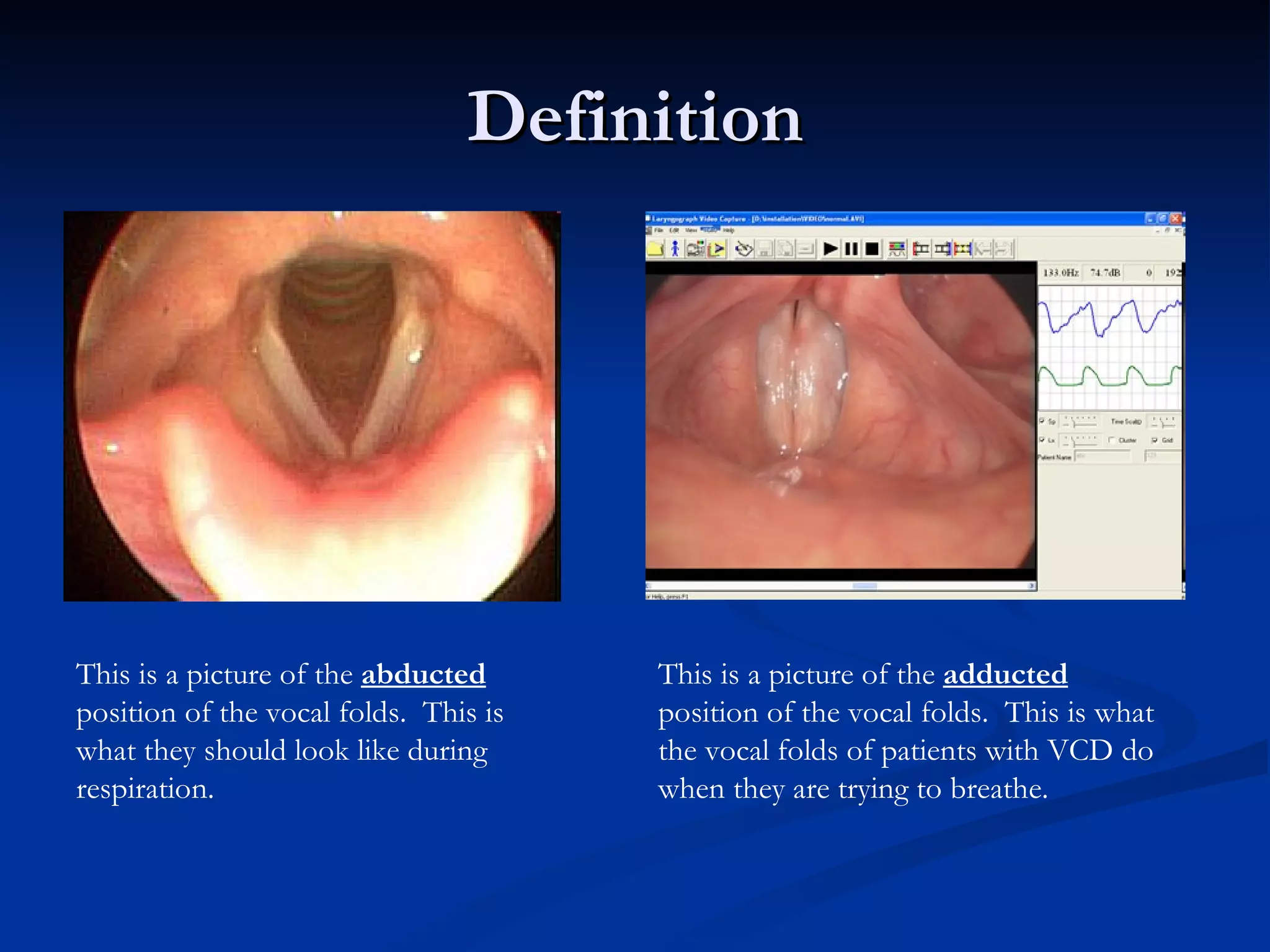

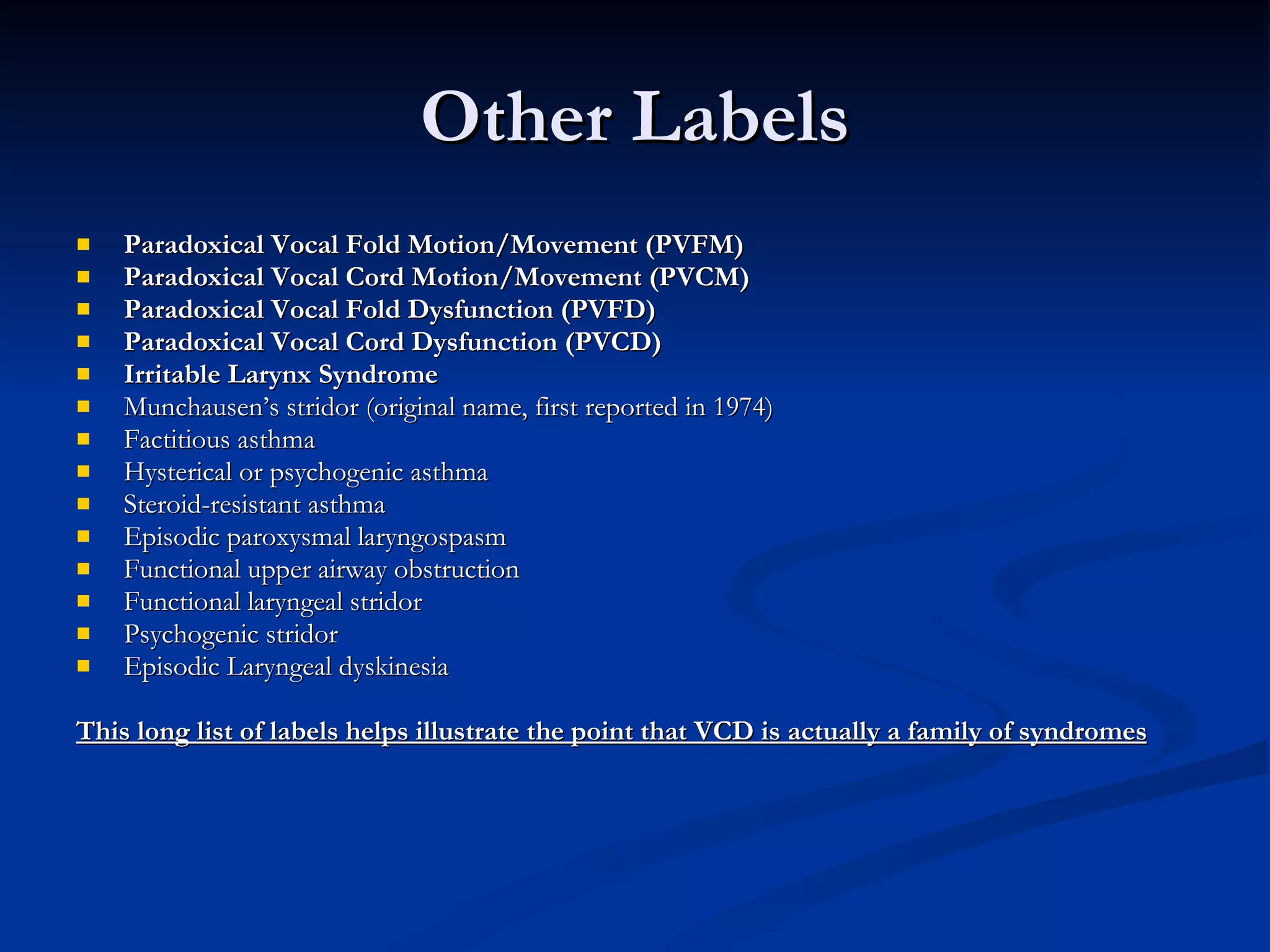

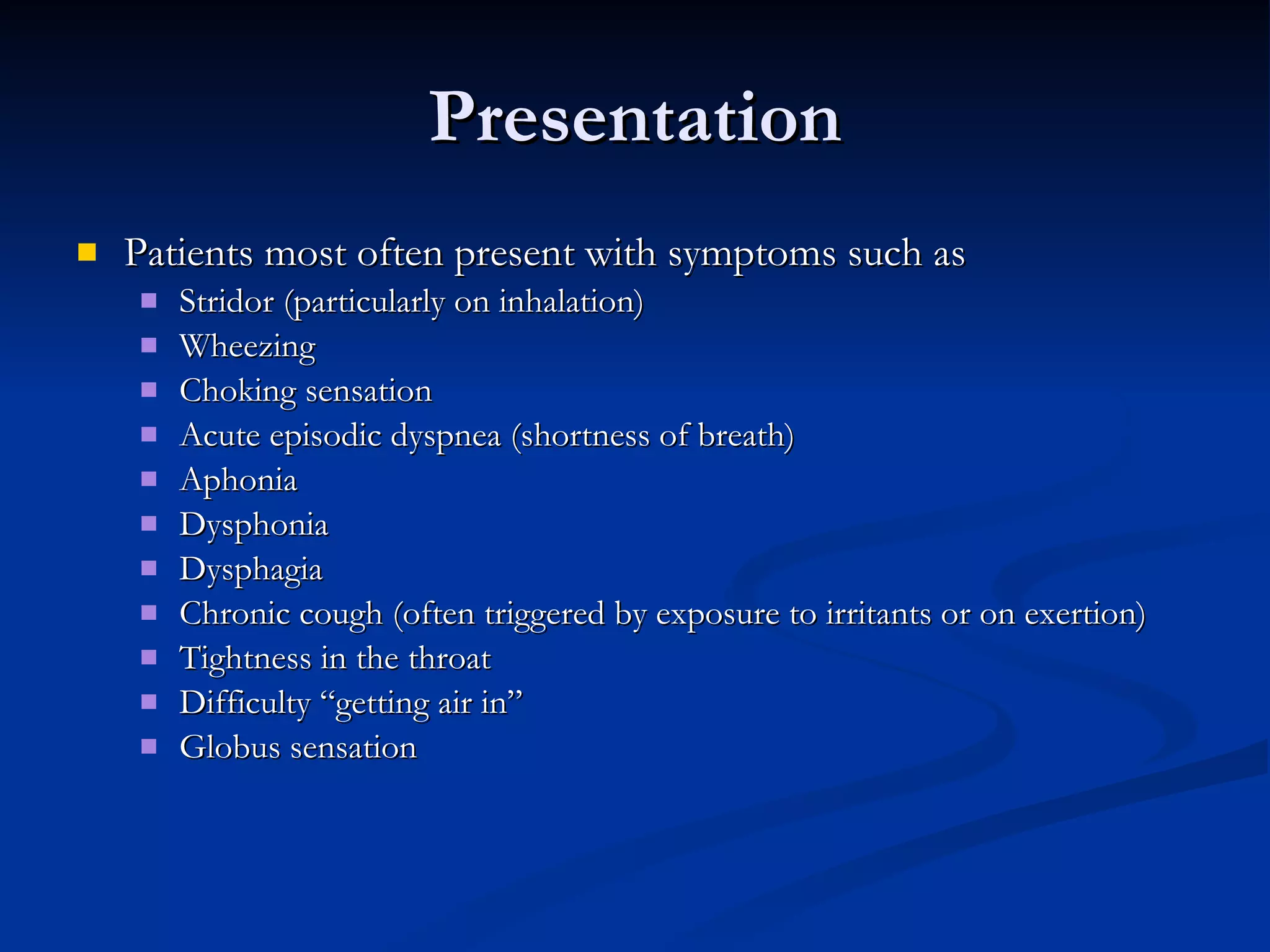

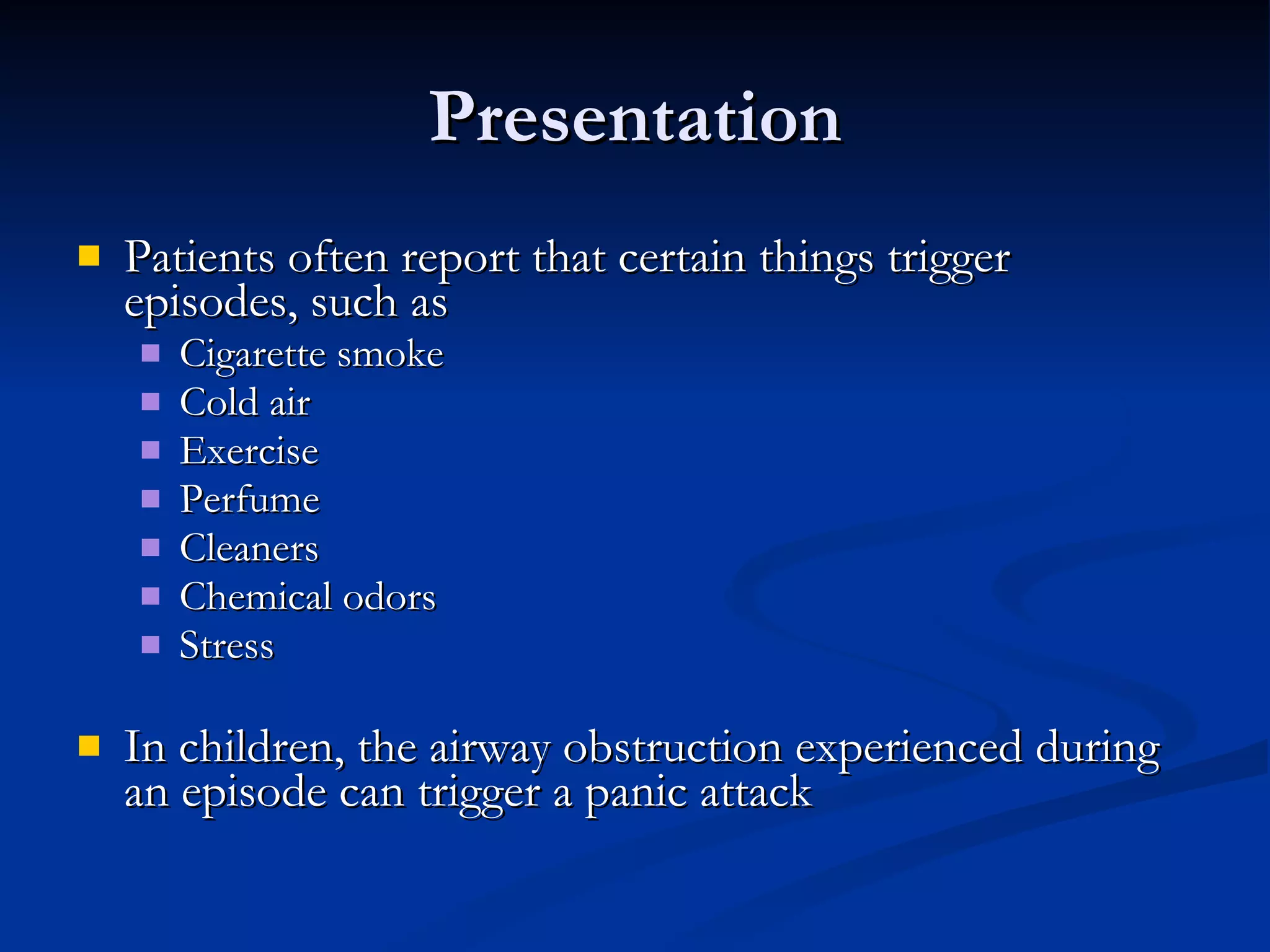

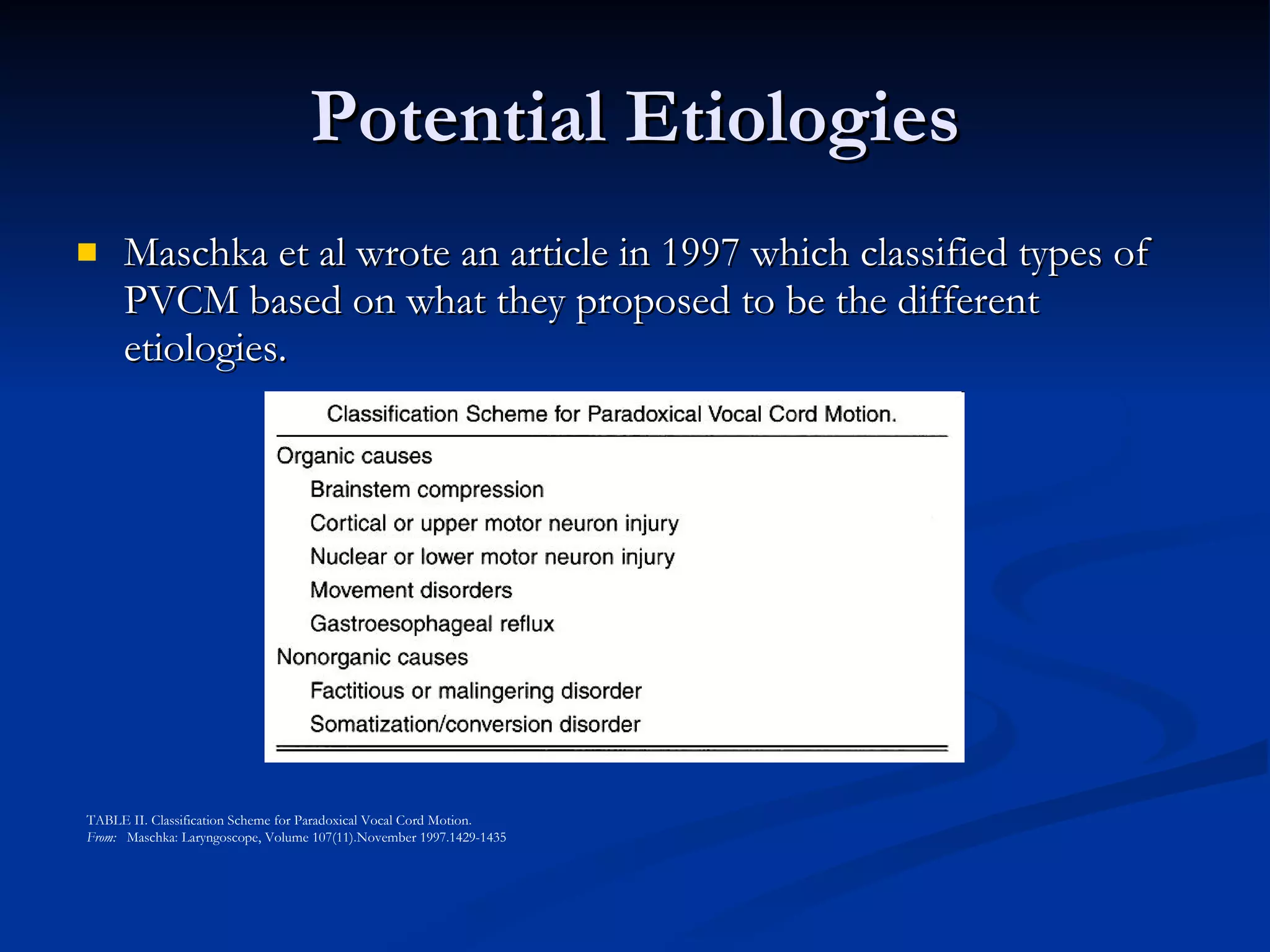

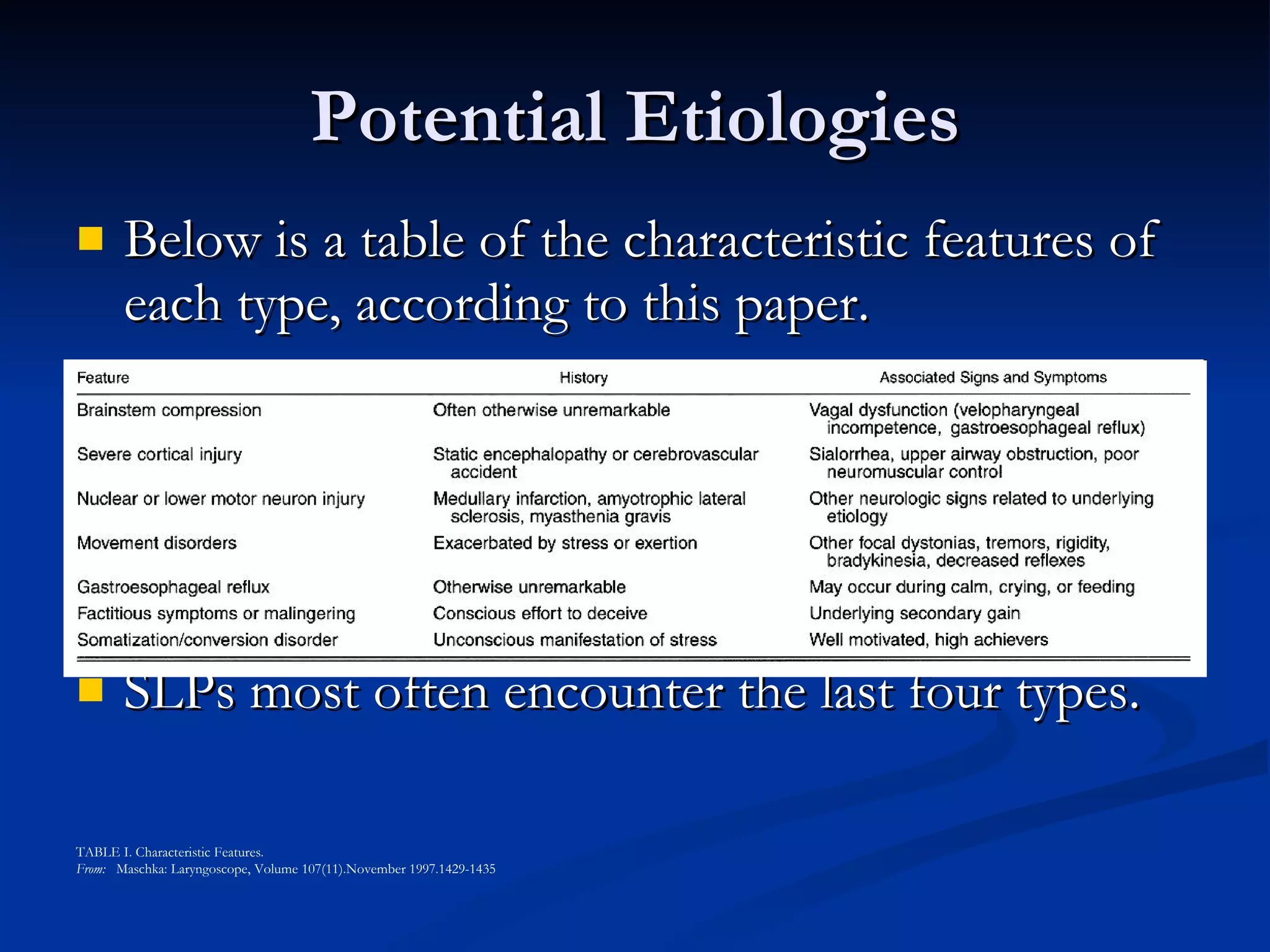

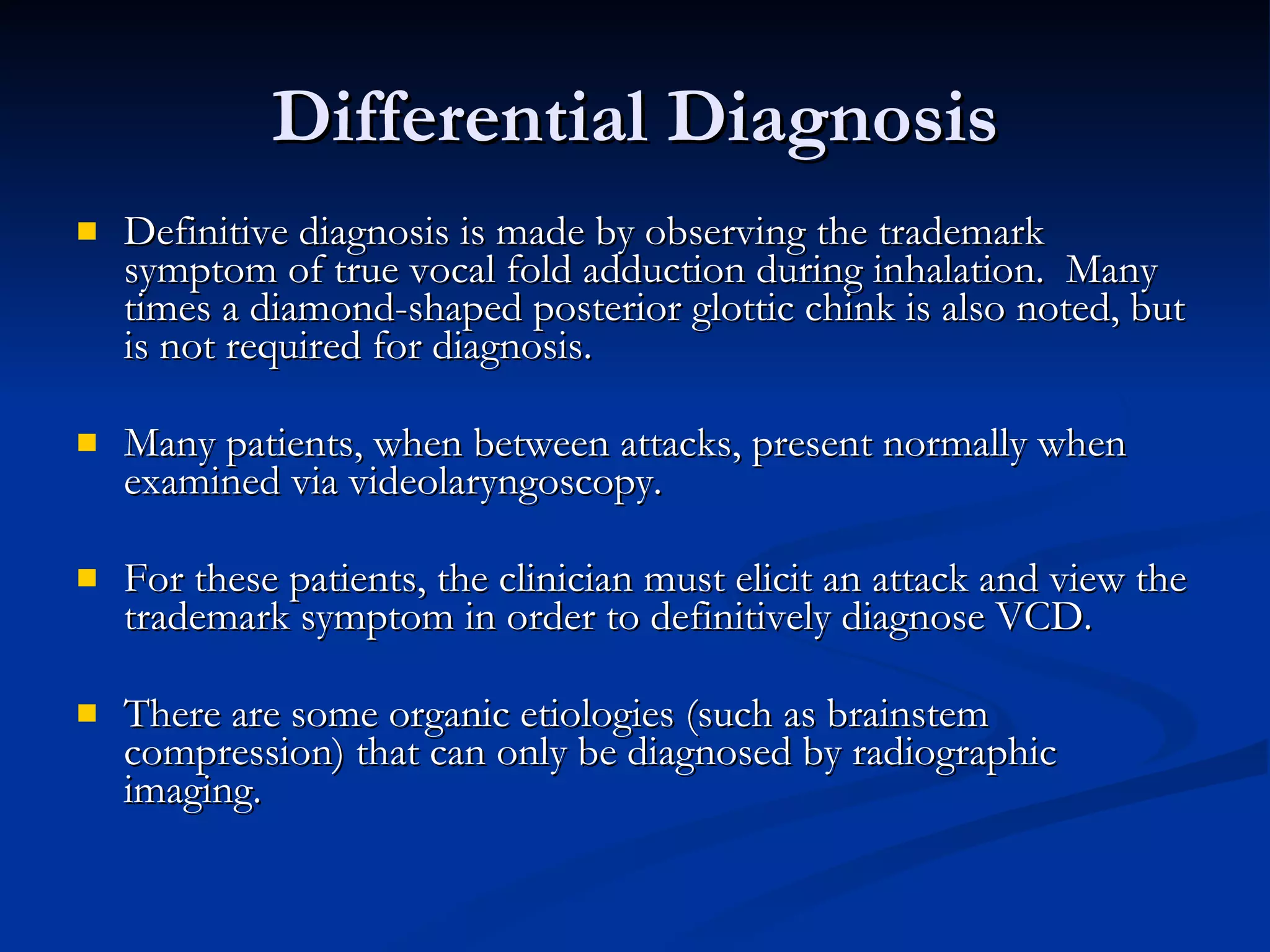

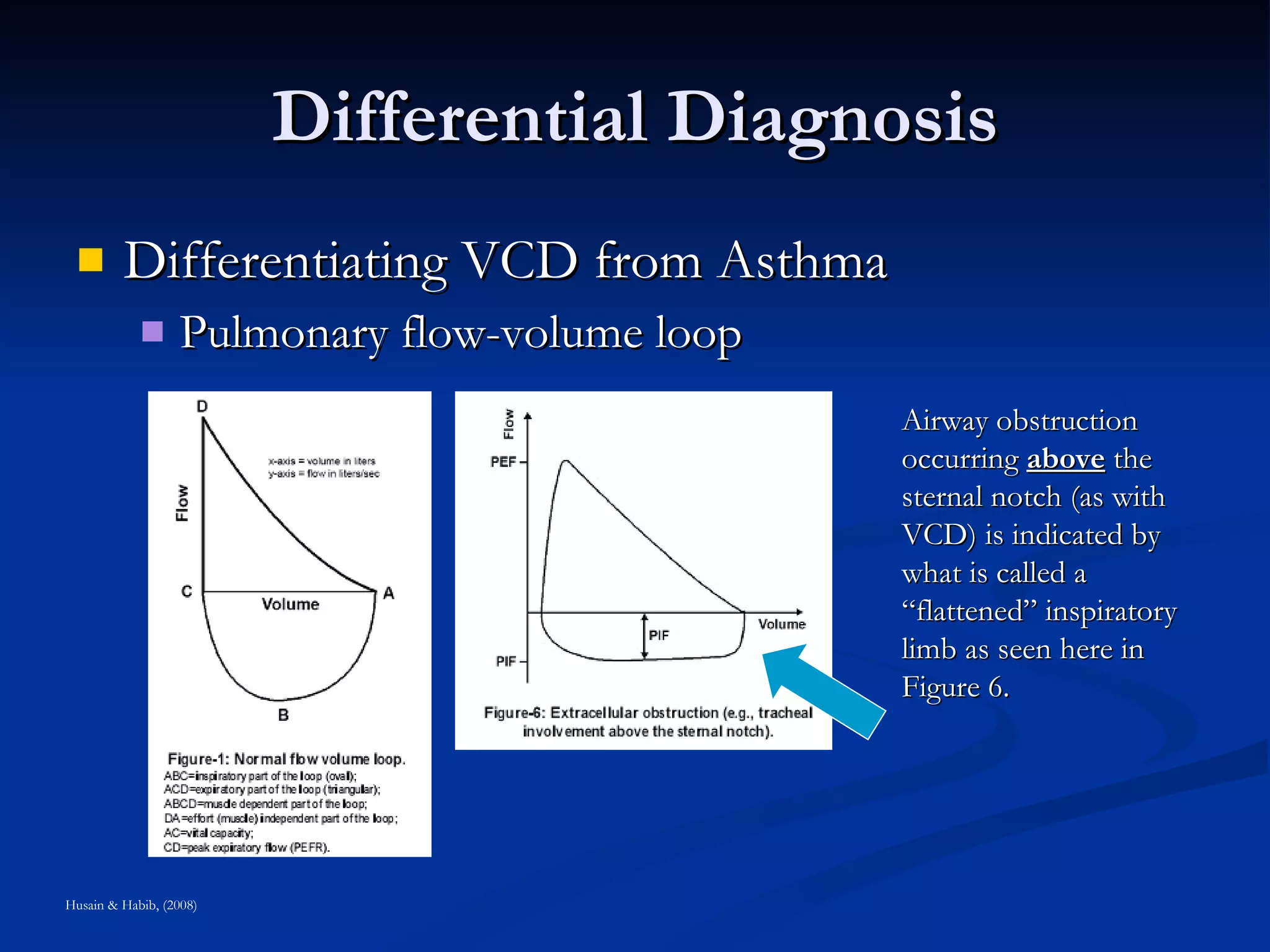

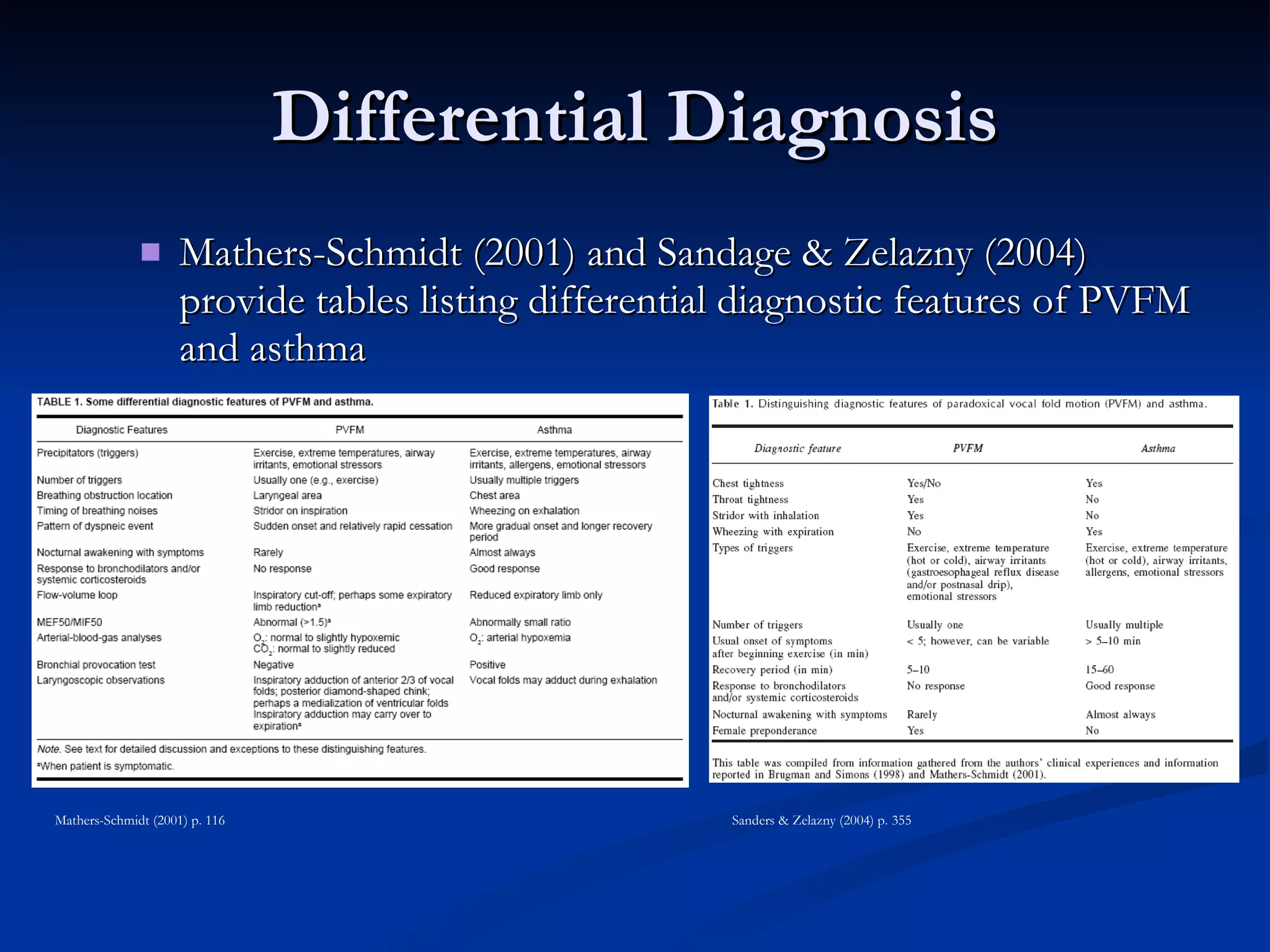

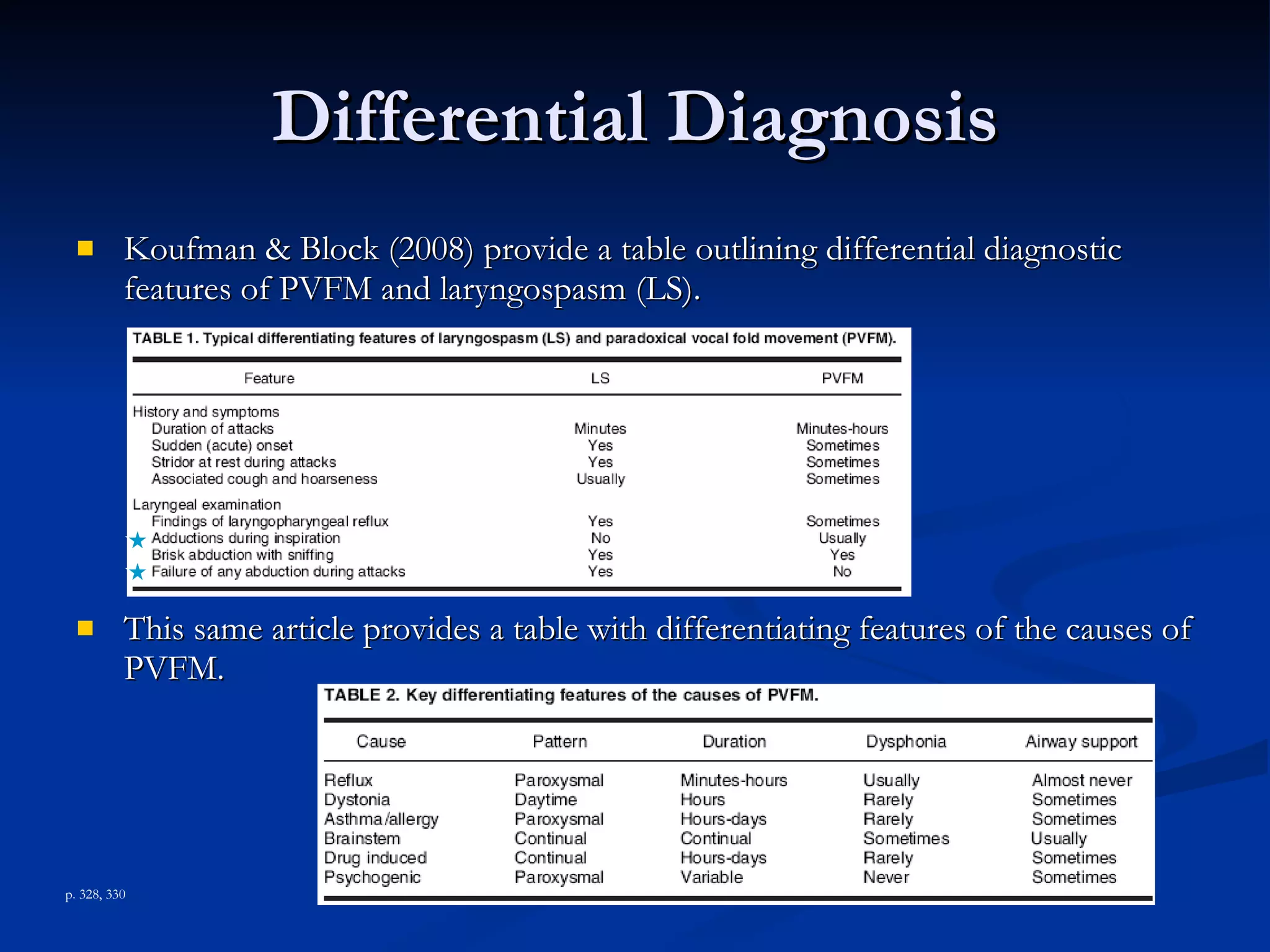

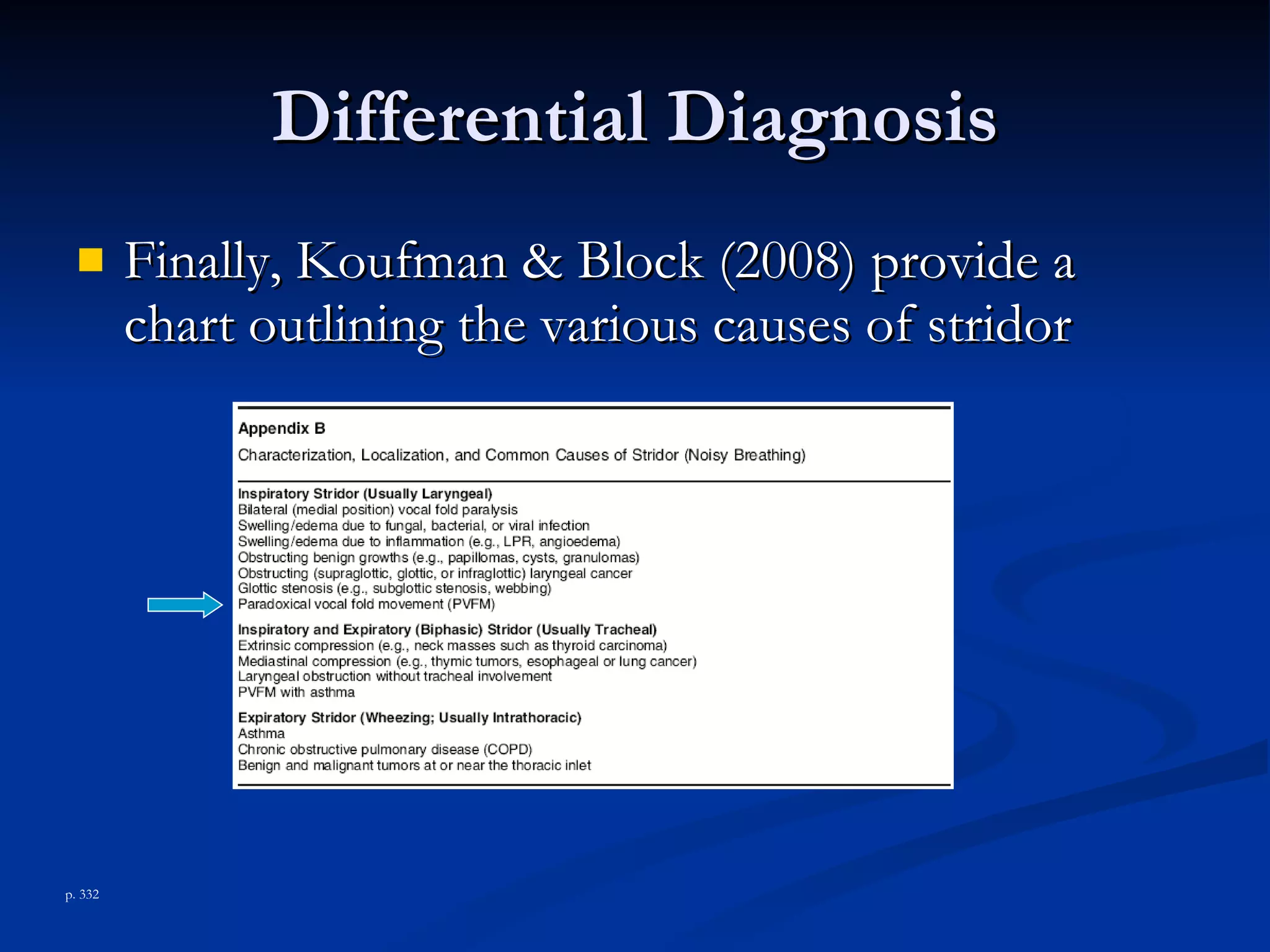

This document provides an overview of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD), including its definition, presentation, potential etiologies, differential diagnosis, and treatment approaches. VCD involves adduction of the vocal cords during inhalation, exhalation, or both, resulting in respiratory symptoms. It is often misdiagnosed as asthma but requires a team-based diagnosis and treatment plan involving medical, speech therapy, and potentially psychiatric interventions.