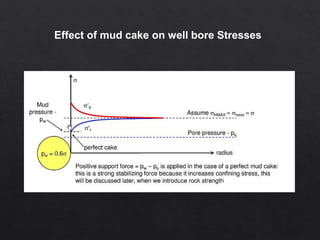

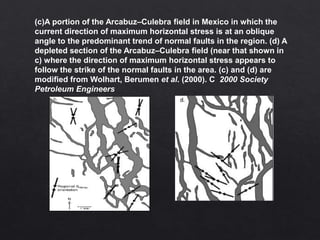

The document discusses factors affecting wellbore stability, including the integration of rock densities and the impact of bedding angles on rock strength. It highlights the challenges of drilling in offshore areas, particularly in relation to pore pressure and fracture gradients affecting mud weight requirements. Additionally, it addresses stress changes surrounding reservoirs during depletion and their implications for faulting behavior in various tectonic settings.