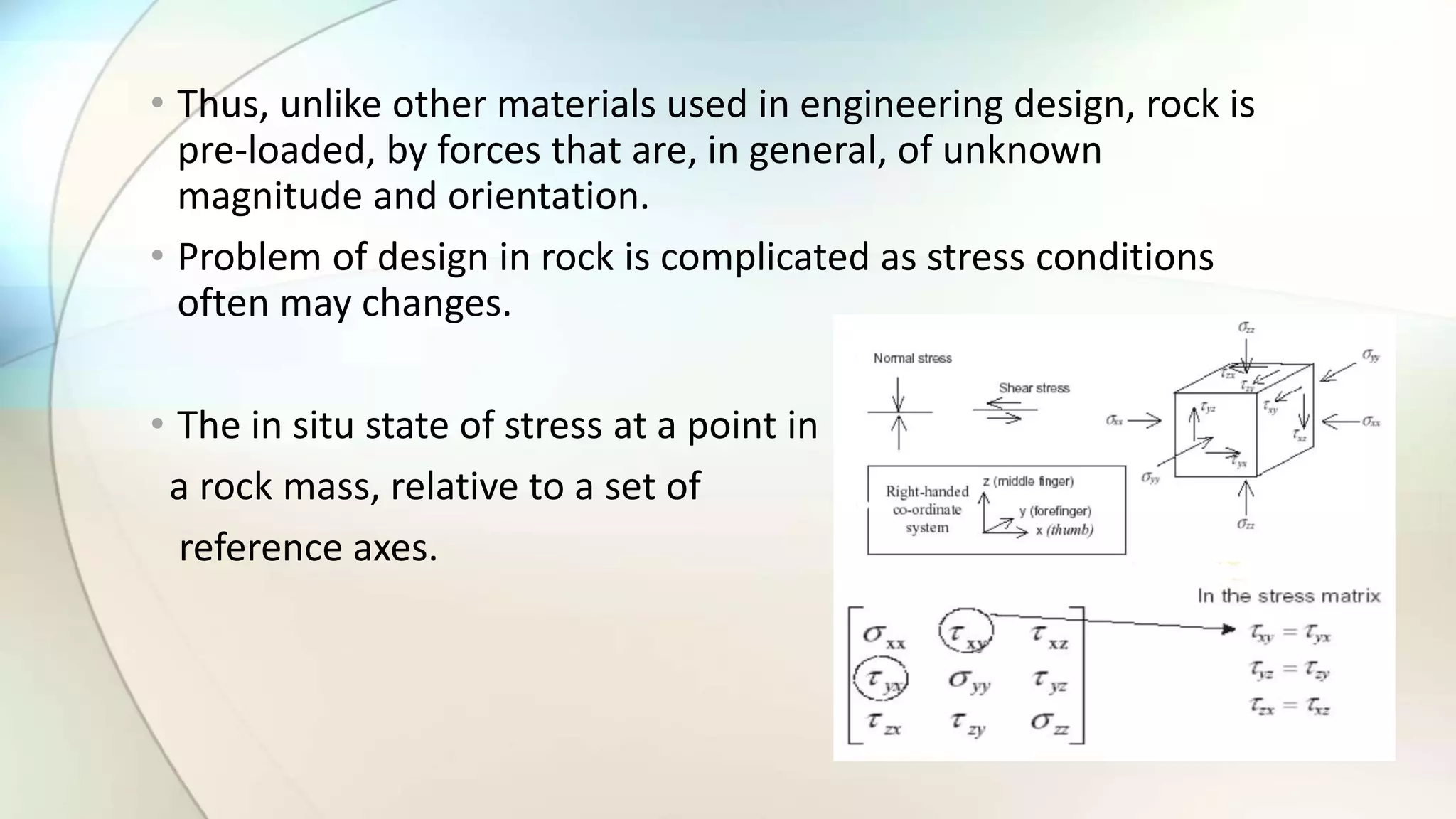

The document discusses in-situ stress in rock mechanics, emphasizing the complexities of stress conditions and their impact on mining design and excavation due to changes in loading and geological factors. It outlines various methods for stress analysis, including physical and computational approaches, highlighting their advantages and limitations. Techniques such as the flat jack and overcoring methods for measuring in-situ stresses are described, detailing their procedures and challenges.