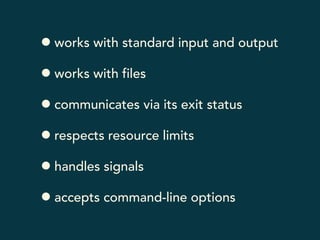

The document discusses best practices for writing well-behaved Unix utilities in Ruby. It recommends that such utilities:

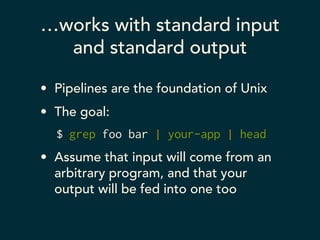

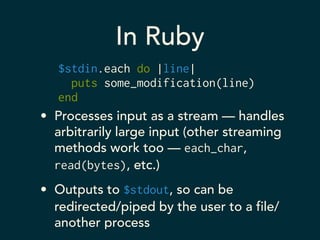

1) Work with standard input and output by reading from $stdin and writing to $stdout so they can be used in pipelines.

2) Work with files by reading from ARGV and using ARGF so they can process single files or multiple files.

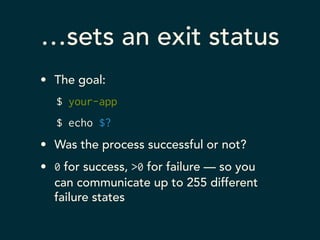

3) Communicate status via exit codes to indicate success or failure.

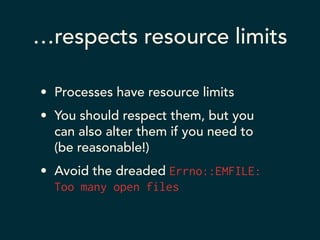

4) Respect system resource limits and handle errors related to limits elegantly.

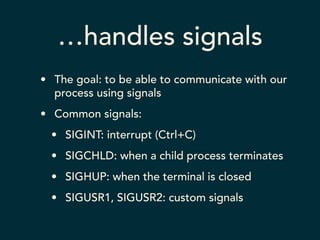

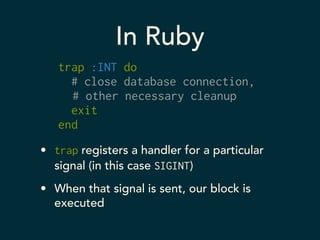

5) Handle signals gracefully to allow communication via signals like Ctrl-C.

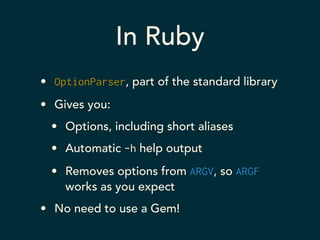

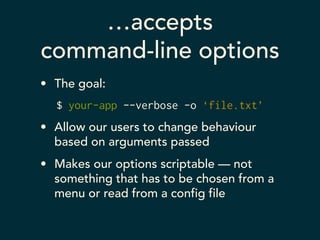

6) Accept command line options using a library like OptionParser for flexibility.

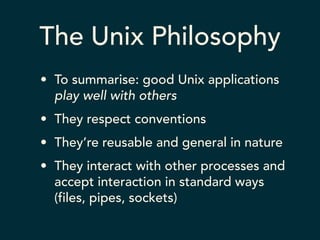

![The Unix Philosophy

“…no single program or idea makes

[Unix] work well. Instead, what makes it

effective is the approach to

programming… at its heart is the idea

that the power of a system comes more

from the relationships among programs

than from the programs themselves.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/well-behavedunix-141014071028-conversion-gate02/85/Writing-Well-Behaved-Unix-Utilities-8-320.jpg)

![In Ruby

require “optparse”

!

options = { verbose: false }

OptionParser.new do |opts|

opts.banner = "Usage: app.rb [options]"

!

opts.on("-v", "--verbose") do |v|

options[:verbose] = true

end

end.parse!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/well-behavedunix-141014071028-conversion-gate02/85/Writing-Well-Behaved-Unix-Utilities-28-320.jpg)