1) The document describes a study on wafer-scale fabrication of nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide (N-rGO) with enhanced quaternary-N content for high-performance photodetection.

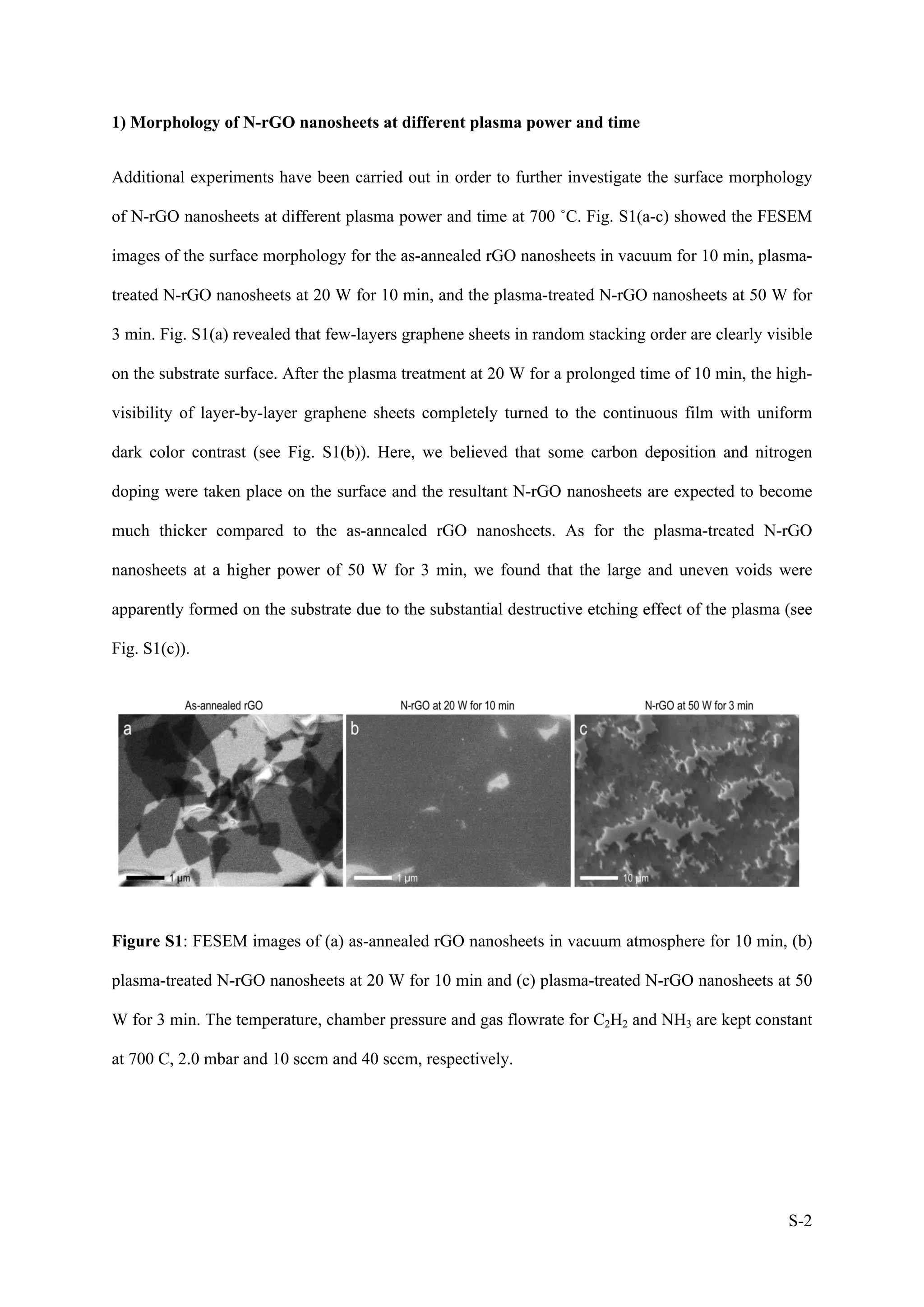

2) Various characterization techniques were used to analyze the morphology, atomic structure, elemental composition and defects of N-rGO produced under different plasma treatment conditions. N-rGO treated at 20W for 10min showed uniform film formation with nitrogen doping and carbon deposition.

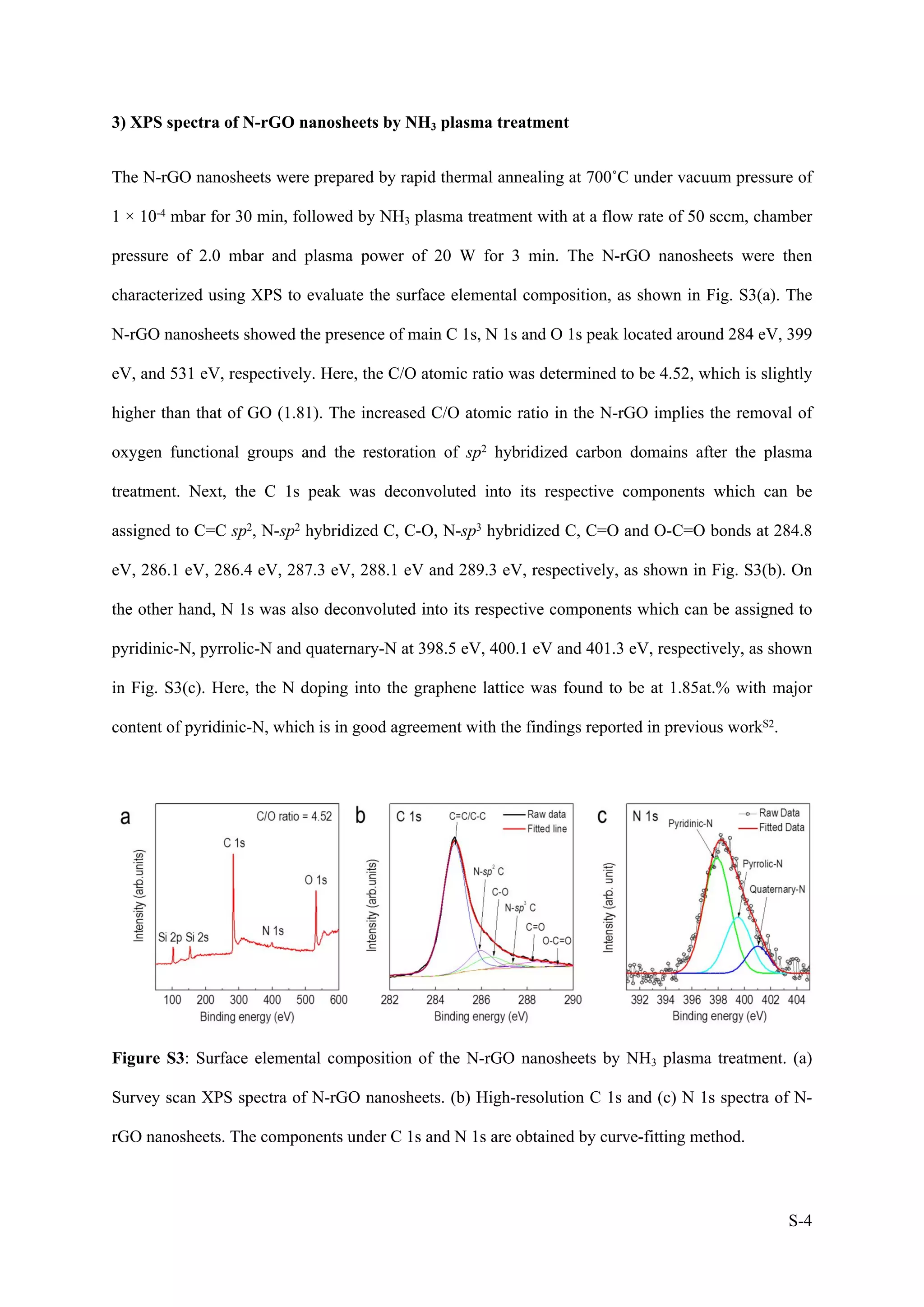

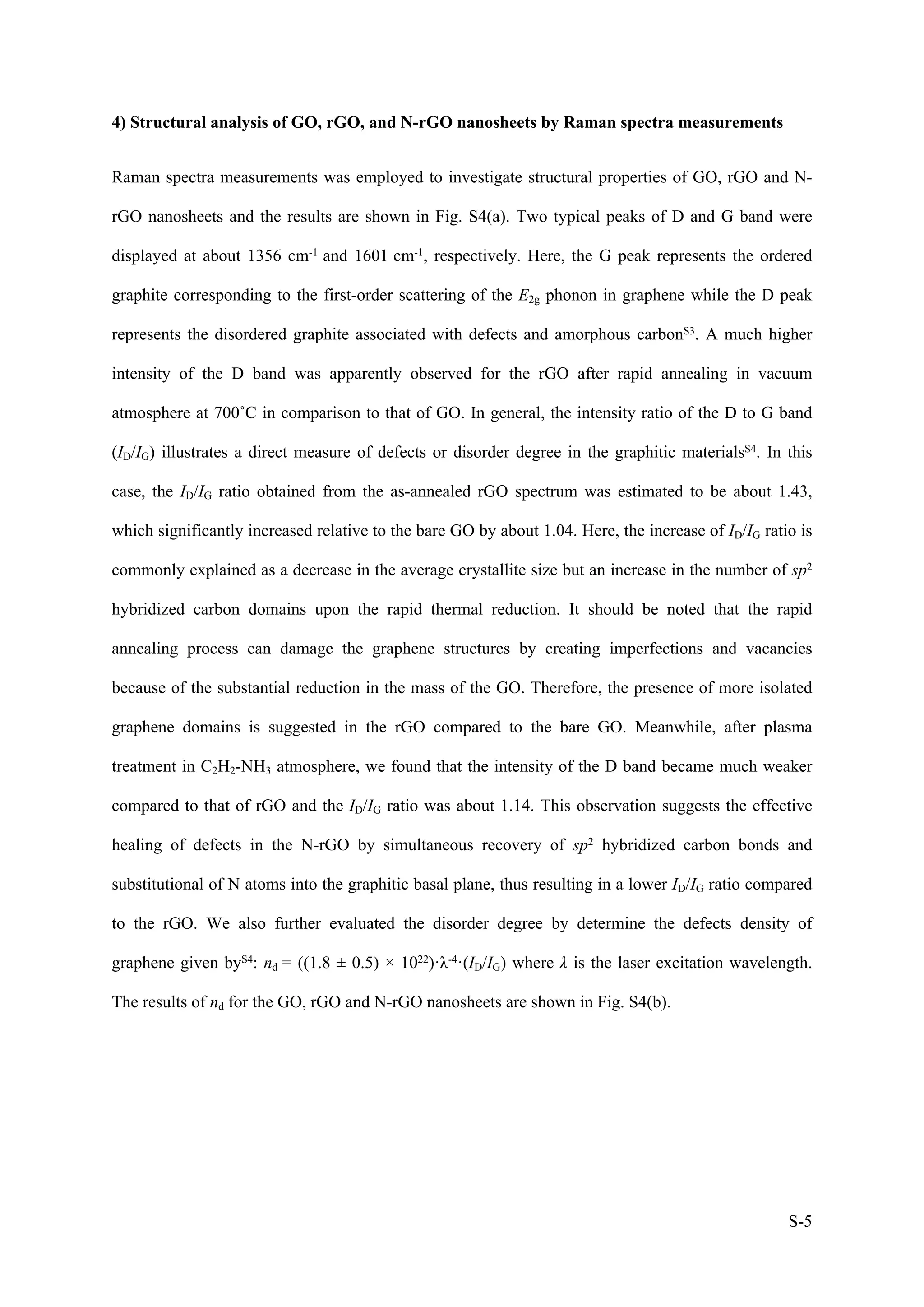

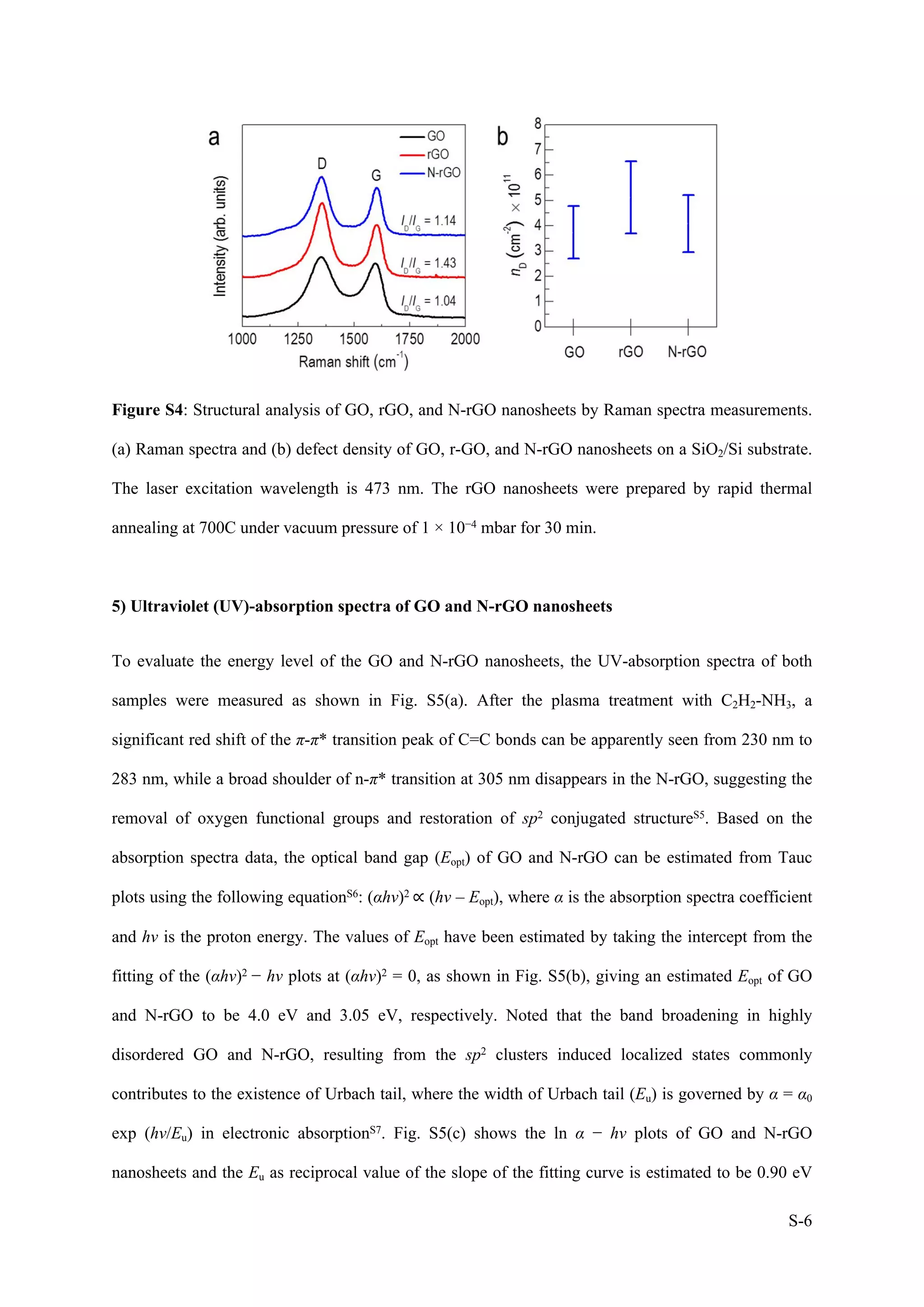

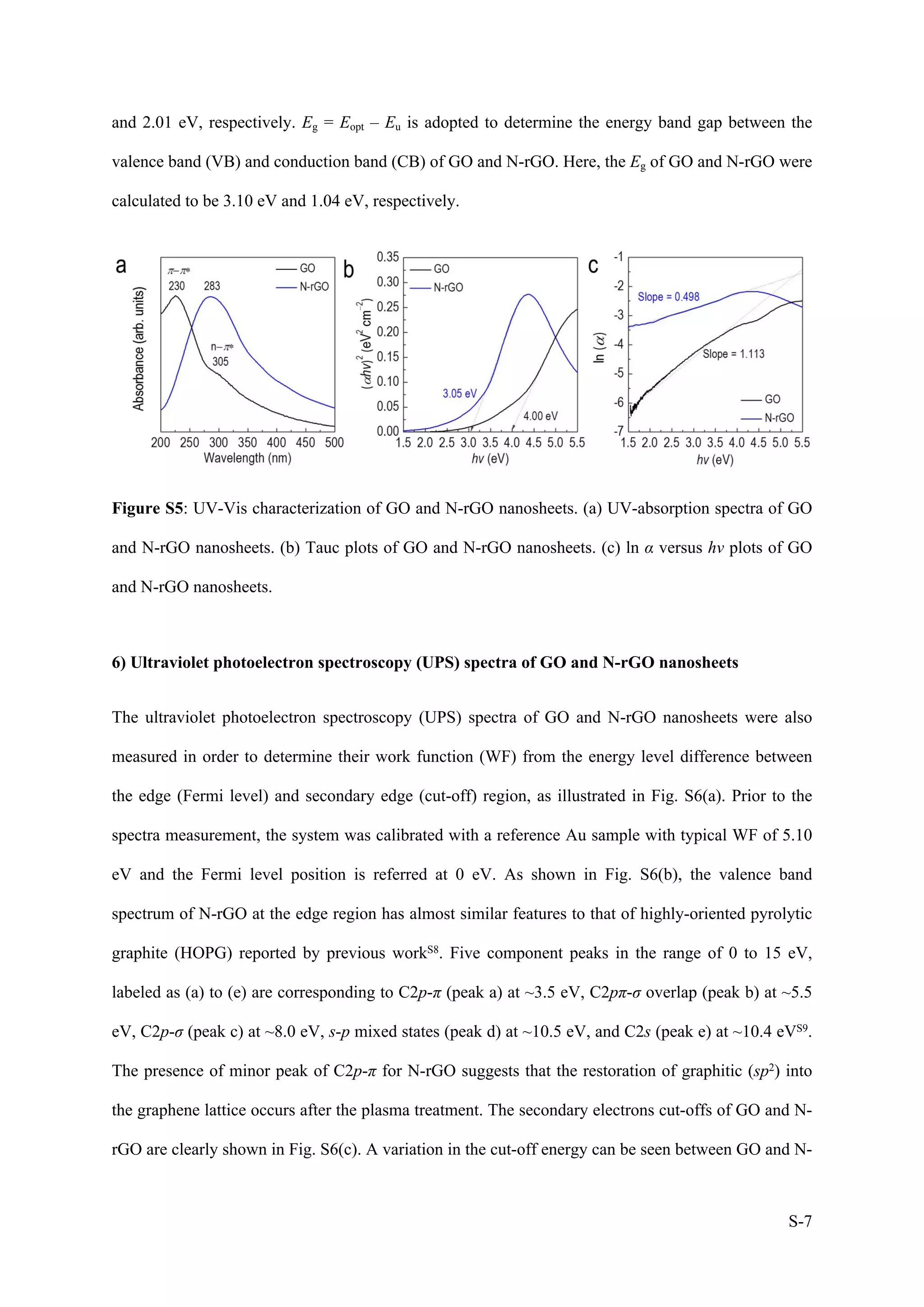

3) XPS and Raman analysis confirmed the incorporation of nitrogen into the graphene lattice, with major pyridinic-N content. This reduced defects and improved the structural and electronic properties of N-rGO compared to reduced graphene oxide

![S-3

2) Atomic structure of N-rGO nanosheets

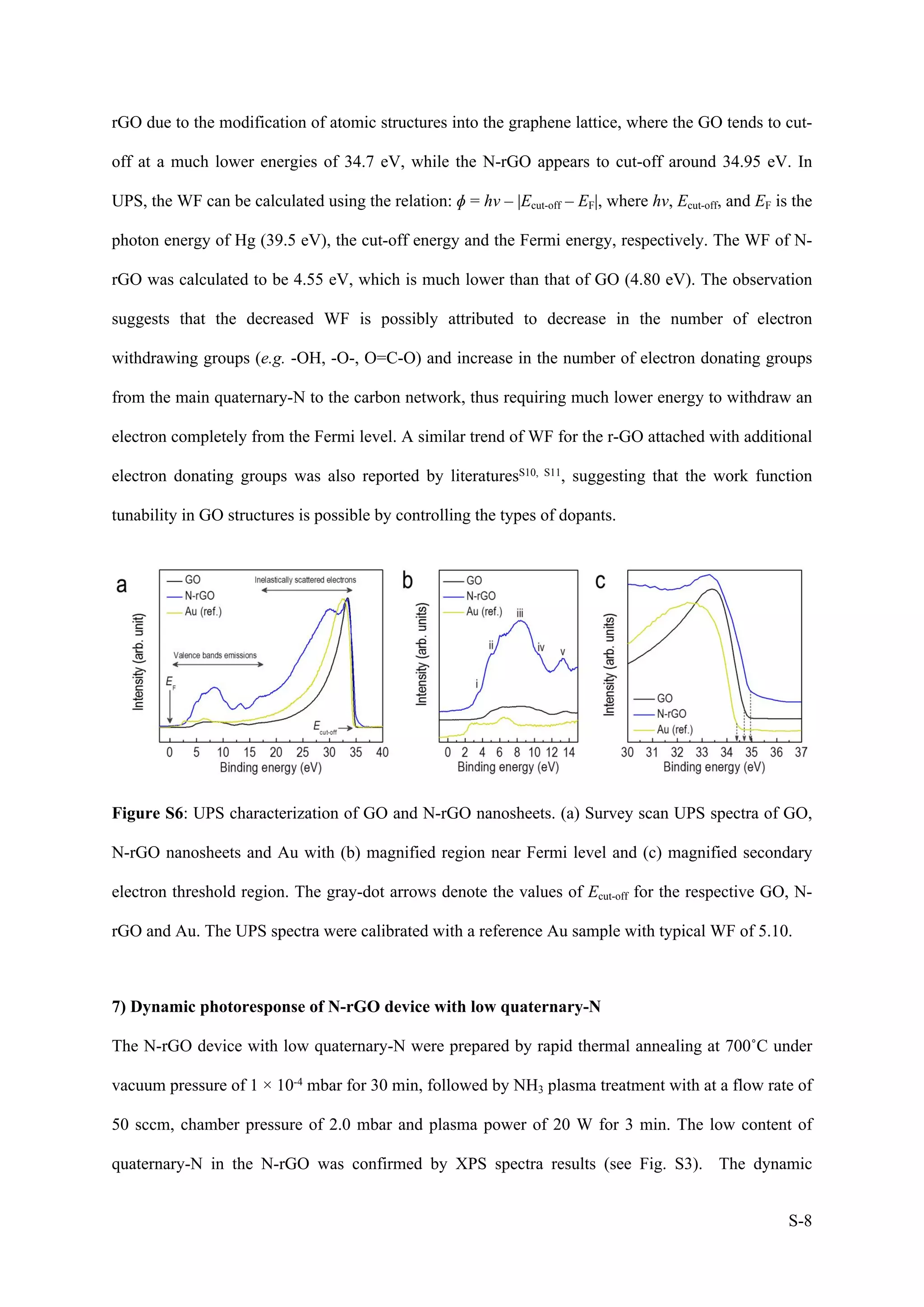

The atomic structure of N-rGO nanosheets incorporated onto the device structure was characterized

by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). Fig. S2(a) displayed a low

magnification bright field TEM image of N-rGO nanosheets, illustrating few layers with few wrinkles

and crumped balls after the plasma treatment. These features are possibly attributed to the variation of

thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) between GO and the substrate due to rapid heating or cooling as

discussed in the literatureS1. In the Fig. S2(b), HR-TEM image on the selected yellow area showed

quadrilaterals like shaped of few layers graphene where the graphene domains seem to be oriented

randomly with rotational stacking fault. This rotation was further confirmed by its corresponding FFT

pattern, as shown in the inset of Fig. S2(b), which revealed a clear ring shaped consisting of many

diffraction spots. Furthermore, this stacking nature of graphene layers can be also seen through SAED

characterization, as shown in Fig. S2(c). Here, we observed multiple hexagonal rings of different spot

intensities along [001] axis, confirming the presence of rotational stacking fault in the N-rGO

nanosheets. The interplanar distances were determined to be ~0.25 nm and ~0.14 nm corresponding to

the (100) and (110) planes, respectively.

Figure S2: Atomic structure of N-rGO nanosheets. (a) TEM image of N-rGO nanosheets with

wrinkles and crumpled balls formation. The yellow triangles indicate the crumpled balls. (b) HR-

TEM image of N-rGO nanosheets. The inset shows the FFT pattern on the selected yellow square

area. (c) SAED image of N-rGO nanosheets observed along the [001] zone axis.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wafer-scalefabricationofnitrogen-dopedreducedgrapheneoxidewithenhancedquaternary-nforhigh-performanc-211202055914/75/Wafer-scale-fabrication-of-nitrogen-doped-reduced-graphene-oxide-with-enhanced-quaternary-n-for-high-performance-photodetection-3-2048.jpg)