Variation in crop genomes and heterosis

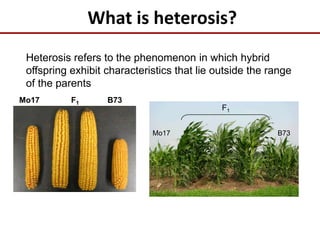

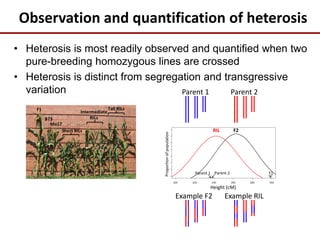

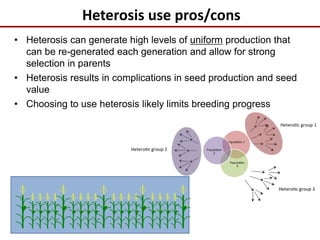

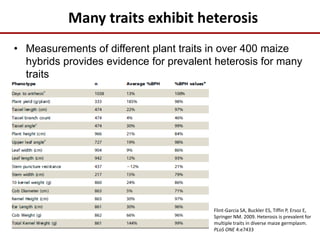

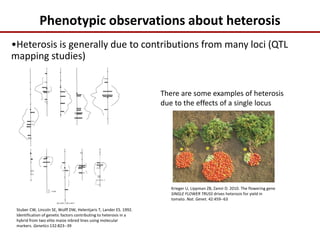

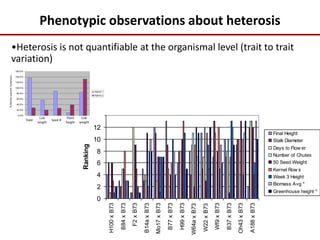

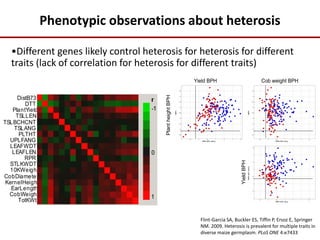

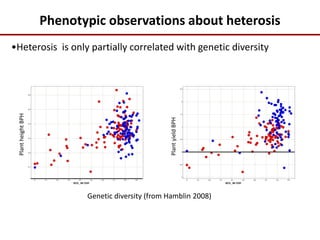

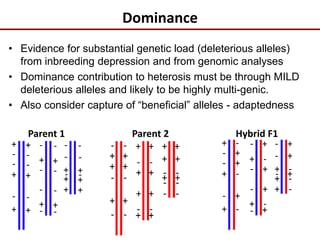

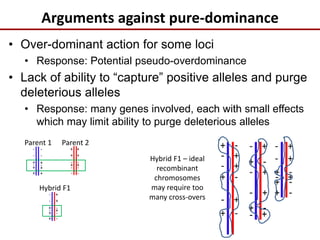

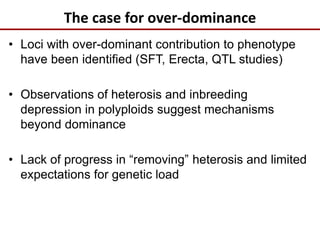

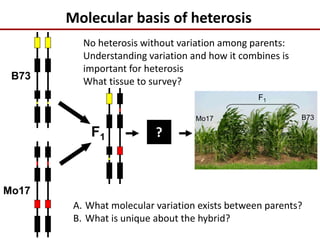

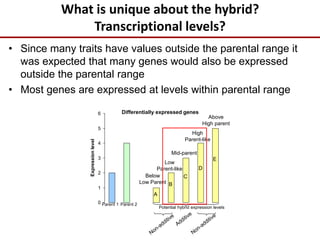

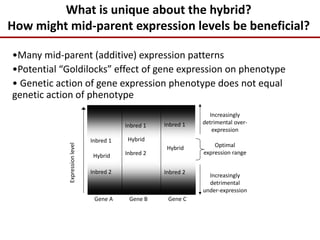

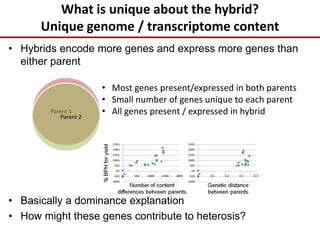

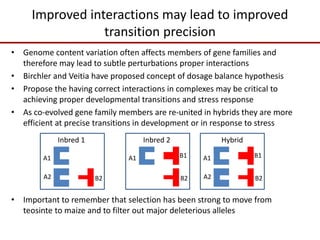

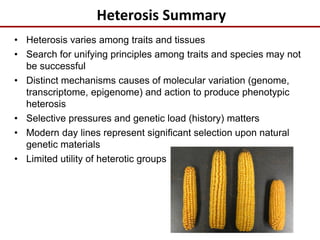

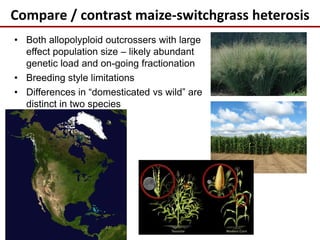

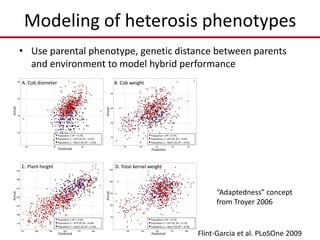

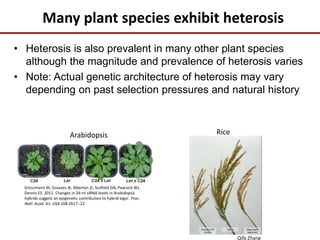

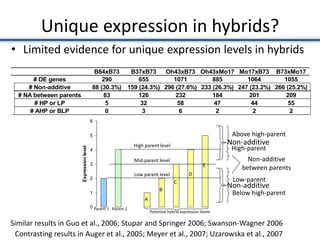

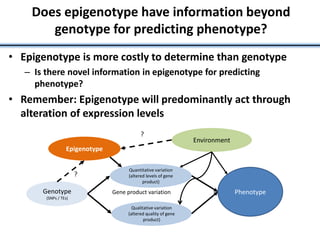

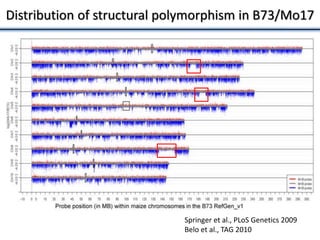

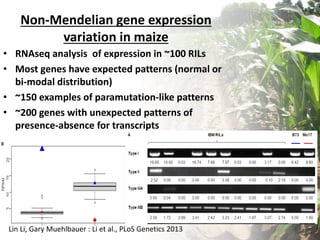

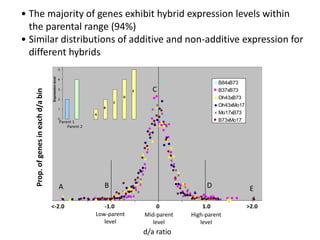

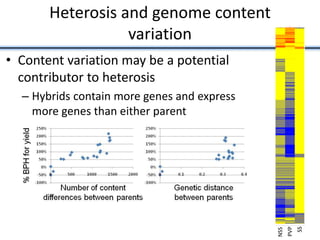

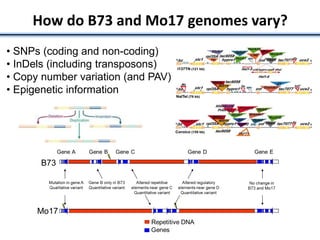

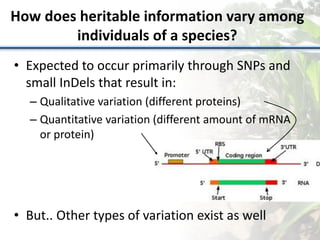

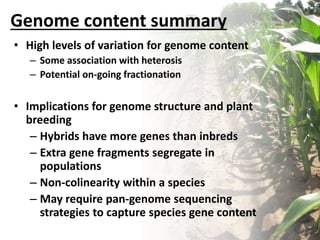

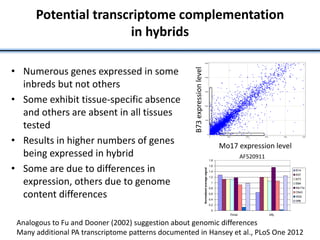

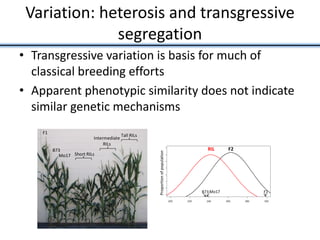

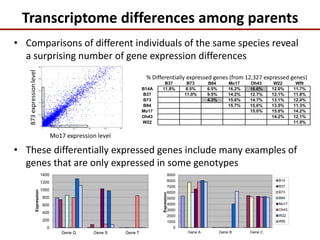

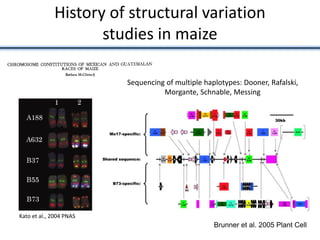

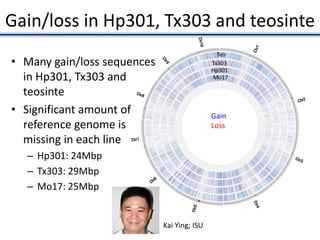

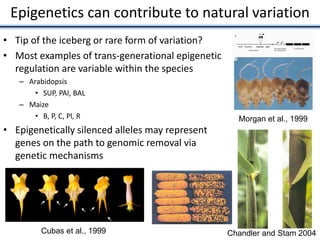

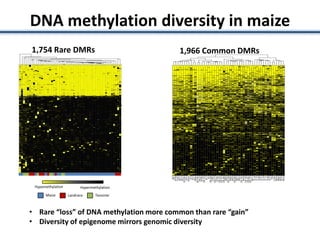

This document discusses sources of genetic variation in crop genomes including single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions/deletions, transposons, epigenetics, and expression level differences. It explores how prevalent these types of variation are and how they behave in plant breeding. The document also discusses heterosis, or hybrid vigor, and how transgressive segregation contributes to phenotypic diversity. Molecular mechanisms underlying heterosis like dominance, overdominance, and gene expression levels in hybrids are examined. While many genes are expressed at mid-parent levels in hybrids, some are uniquely present or expressed. The potential role of improved gene interactions restoring proper developmental transitions and stress responses in hybrids is proposed.

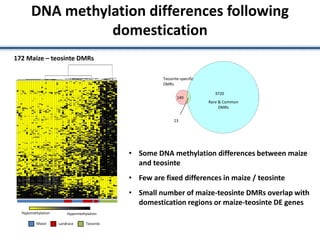

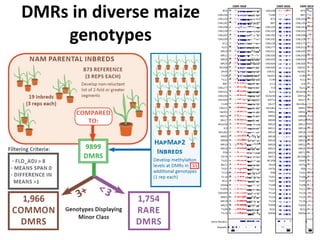

![• Identified nearest genes to each DMR (2,375 genes within 10kb of DMR) and

assessed correlation with transcript abundance

•277 (of 2,375 tested) had a significant (q<0.01) negative correlation with

expression [53 genes exhibited a positively correlation]

•No significant GO enrichments; many genes lack syntenic orthologs in other

species (TEs or novel genes)

• ~0.7% of all genes expression associated with nearby DNA methylation variation

Functional Consequences of DMRs

Qualitative association Quantitative association](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/springernathan-161104180656/85/Variation-in-crop-genomes-and-heterosis-17-320.jpg)