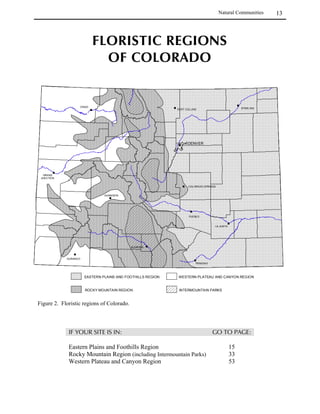

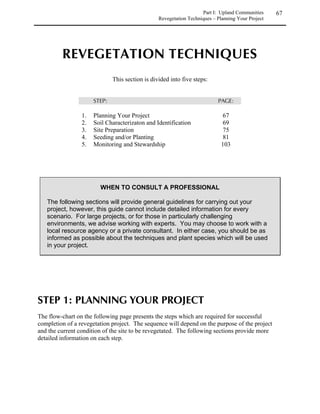

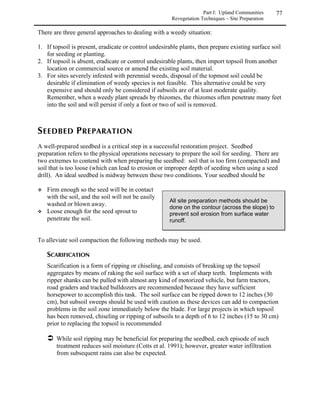

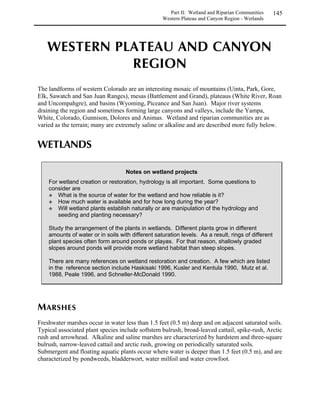

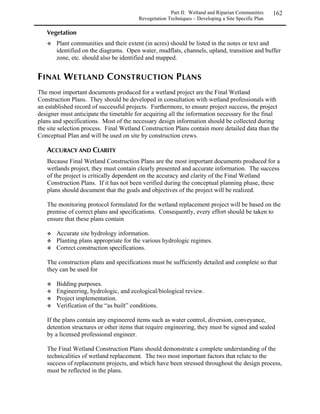

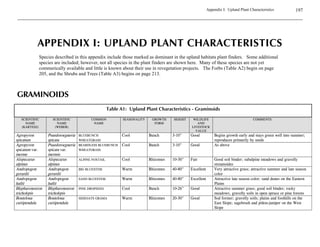

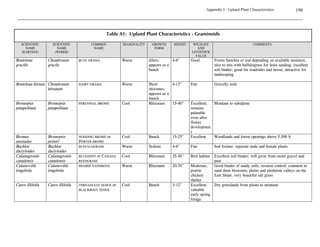

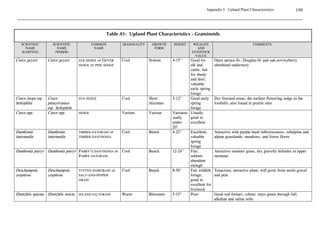

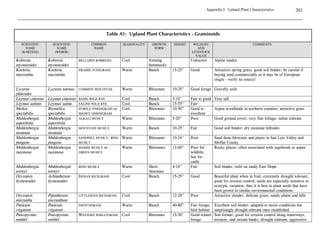

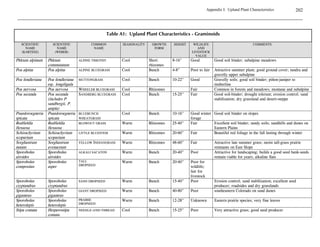

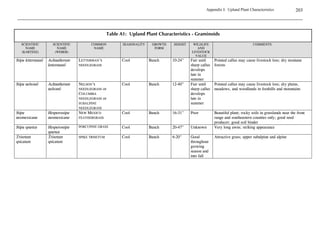

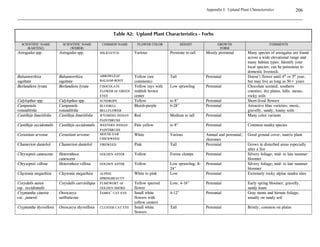

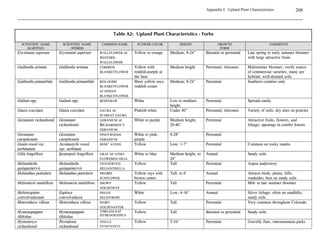

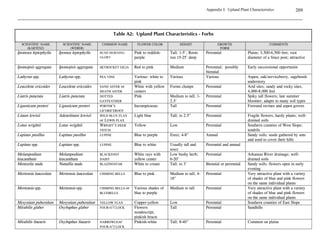

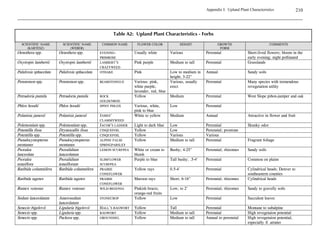

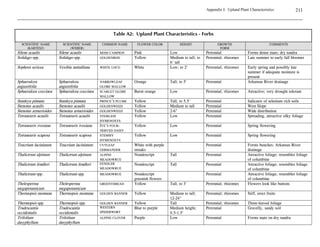

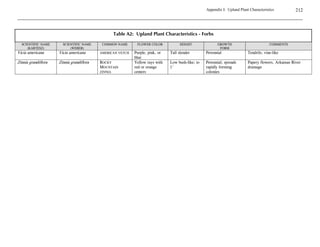

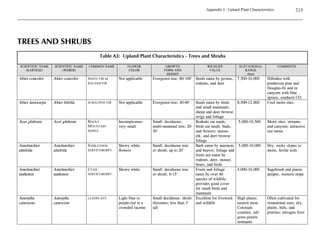

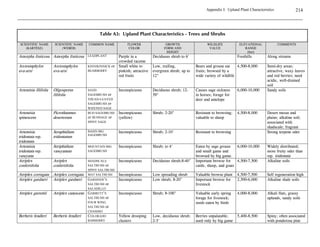

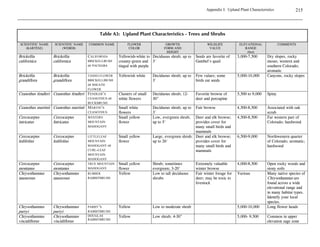

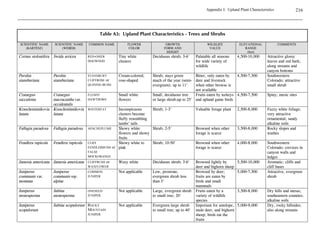

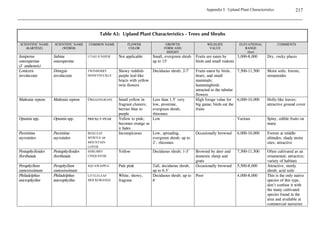

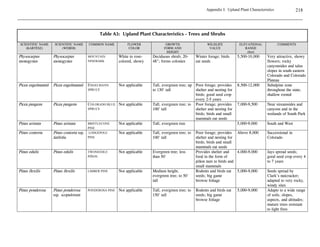

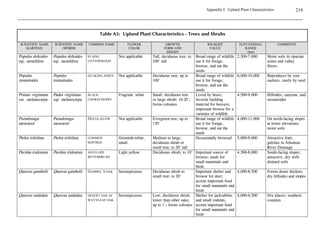

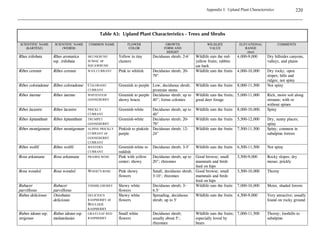

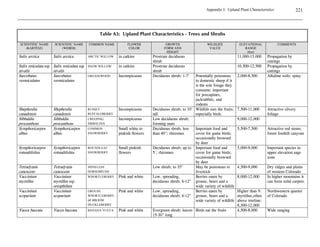

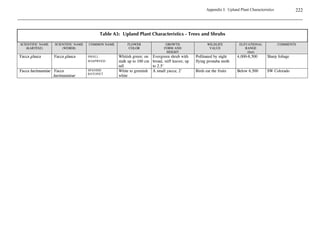

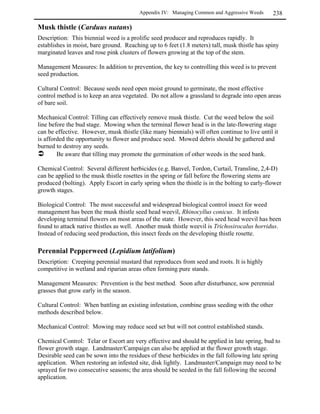

This guide provides information for selecting and establishing native plants in Colorado. It covers plant basics, natural communities in the state, and techniques for revegetation of upland and wetland habitats. The guide includes details on site planning, preparation, seed and plant selection, and monitoring for successful revegetation projects using native species.