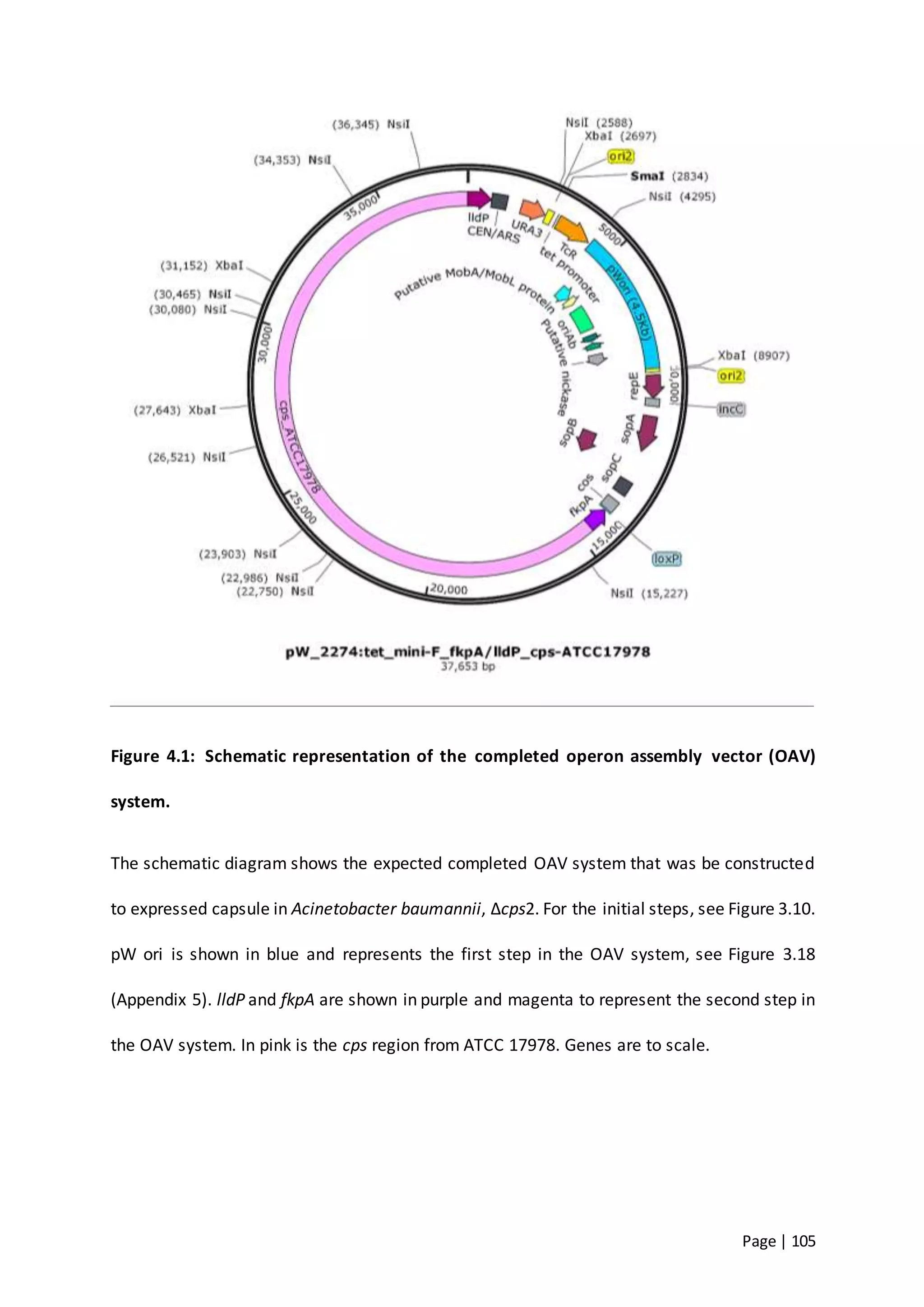

The thesis investigates the role of capsular polysaccharides in the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978, an opportunistic nosocomial pathogen associated with high rates of antimicrobial resistance. The study aims to construct an operon assembly vector to analyze the effects of different capsule types on desiccation persistence, antimicrobial resistance, and other virulence factors. Key findings include the development of an isogenic mutant to examine the impact of capsule absence on bacterial survival and resistance to environmental stressors.

![Page | 119

GIAMARELLOU, H., ANTONIADOU, A. & KANELLAKOPOULOU, K. 2008. Acinetobacter

baumannii: a universal threat to public health? International Journal of Antimicrobial

Agents, 32, 106-119.

GIGUÈRE, D. 2015. Surface polysaccharides from Acinetobacter baumannii: structures and

syntheses. Carbohydrate Research, 418, 29-43.

GOLDMAN, A. S. 1993. The immune system of human milk: antimicrobial, antiinflammatory

and immunomodulating properties. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 12, 664-

672.

GREENE, C., WU, J., RICKARD, A. H. & XI, C. 2016. Evaluation of the ability of Acinetobacter

baumannii to form biofilms on six different biomedical relevant surfaces. Letters in

Applied Microbiology, 63, 233-239.

HANAHAN, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Journal of

Molecular Biology, 166, 557-580.

HARDING, C. M., HENNON, S. W. & FELDMAN, M. F. 2017. Uncovering the mechanisms of

Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16, 91.

HASSAN, K. A., JACKSON, S. M., PENESYAN, A., PATCHING, S. G., TETU, S. G., EIJKELKAMP, B.

A., BROWN, M. H., HENDERSON, P. J. F. & PAULSEN, I. T. 2013. Transcriptomic and

biochemical analyses identify a family of chlorhexidine efflux proteins. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 20254.

HEALTH, D. O. 2017. Medical Devices Safety Update [Online]. Australian Goverment

Available: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/medical-devices-safety-update-

volume-5-number-3-may-2017.pdf [Accessed 21/11/2018 2018].

HOOD, M. I., MORTENSEN, B. L., MOORE, J. L., ZHANG, Y., KEHL-FIE, T. E., SUGITANI, N.,

CHAZIN, W. J., CAPRIOLI, R. M. & SKAAR, E. P. 2012. Identification of an Acinetobacter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesisv9-181227074131/75/Honours-Thesis-130-2048.jpg)

![Page | 128

WANG, N., OZER, E. A., MANDEL, M. J. & HAUSER, A. R. 2014. Genome-wide identification of

Acinetobacter baumannii genes necessaryfor persistence in the lung. MBio, 5, e01163-

14.

WEBER, B. S., HARDING, C. M. & FELDMAN, M. F. 2016. Pathogenic Acinetobacter: from the

cell surface to infinity and beyond. Journal of Bacteriology, 198, 880-887.

WEINSTEIN, R. A., MILSTONE, A. M., PASSARETTI, C. L. & PERL, T. M. 2008. Chlorhexidine:

Expanding the Armamentarium for Infection Control and Prevention. Clinical

Infectious Diseases, 46, 274-281.

WHO. 2017. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed

[Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-02-2017-who-

publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed [Accessed].

WIELAND, K., CHHATWAL, P. & VONBERG, R.-P. 2018. Nosocomial outbreaks caused by

Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Results of a systematic

review. American Journal of Infection Control, 46, 643-648.

WHITFIELD, C.2006. Biosynthesis and assemblyof capsularpolysaccharides in Escherichia coli.

Annu. Rev. Biochem., 75, 39-68.

WILLIS, L. M. & WHITFIELD, C. 2013. Capsule and lipopolysaccharide. Escherichia coli (Second

Edition). Elsevier.

WONG, D., NIELSEN, T. B., BONOMO, R. A., PANTAPALANGKOOR, P., LUNA, B. & SPELLBERG,

B. 2017. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: a

century of challenges. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 30, 409-447.

WOZNIAK, R. A. F. & WALDOR, M. K. 2010. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic

mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nature Reviews

Microbiology, 8, 552.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thesisv9-181227074131/75/Honours-Thesis-139-2048.jpg)