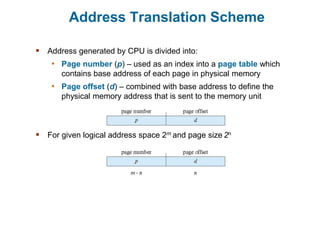

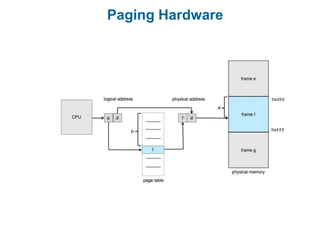

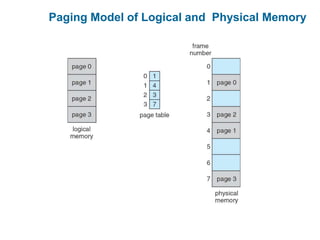

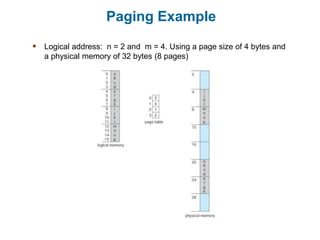

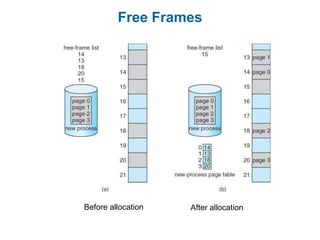

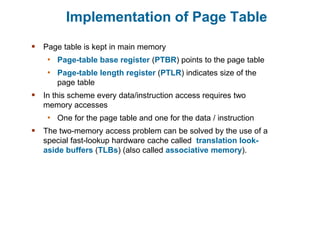

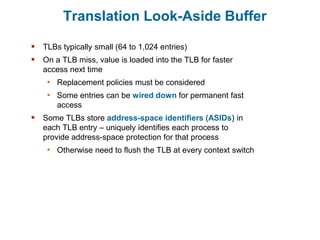

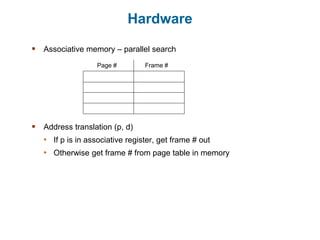

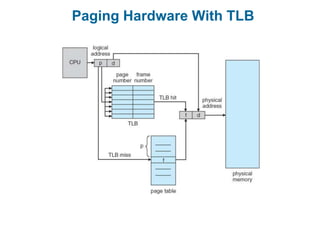

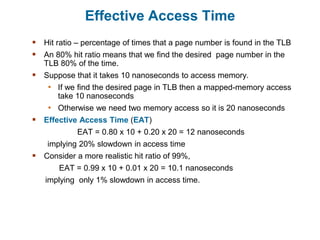

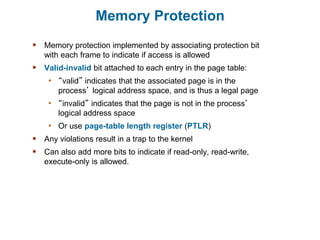

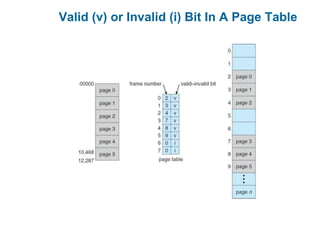

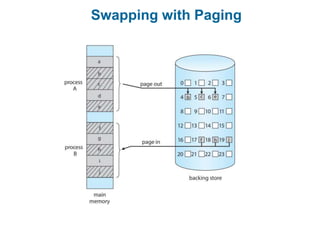

Main memory is used to store programs and data for the CPU to access directly. Paging is a memory management technique that divides main memory into fixed-sized blocks called frames and divides logical memory into same-sized blocks called pages. The page table maps logical page numbers to physical frame numbers, with translation lookaside buffers caching these mappings to improve performance. Protection bits in page table entries enforce access permissions on individual pages.