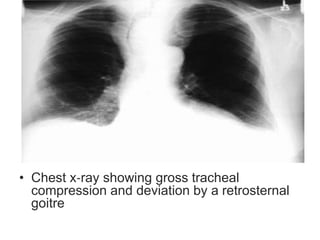

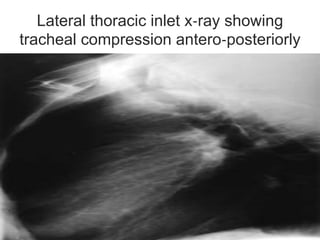

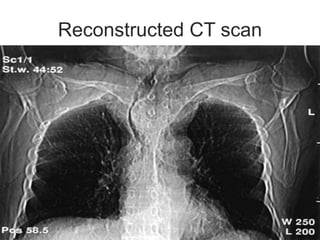

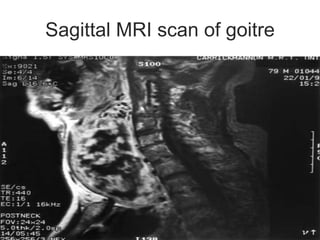

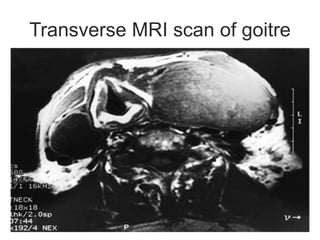

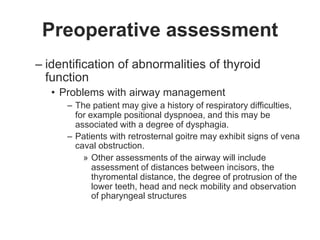

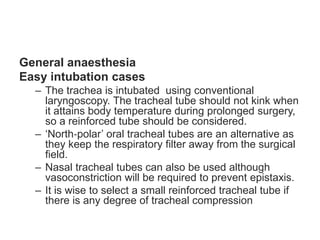

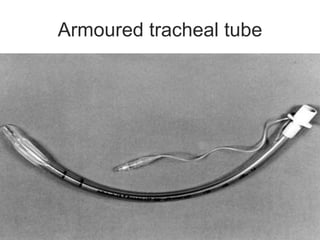

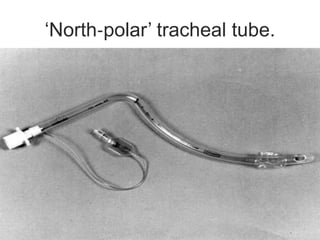

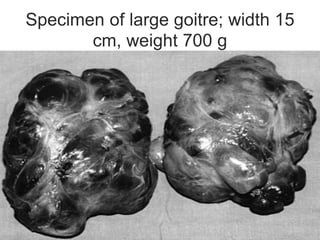

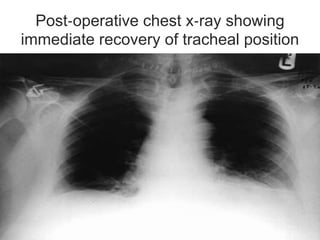

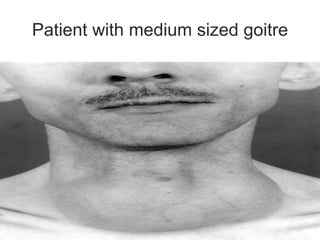

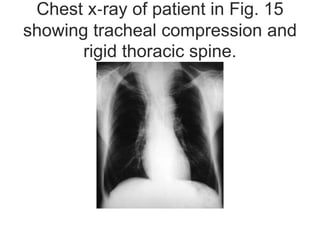

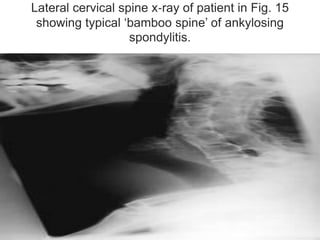

This document discusses the anesthetic considerations for patients undergoing thyroid surgery or with thyroid disease. It covers the effects of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, management of thyroid crisis, indications for thyroidectomy, challenges of large goiters and retrosternal goiters, risks of thyroid cancer and complications of thyroid surgery such as hematoma, nerve injury, and hypocalcemia. Regional or general anesthesia techniques are described. Postoperative care involves monitoring for airway issues and other complications. Surgery in special situations like thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia is also reviewed.