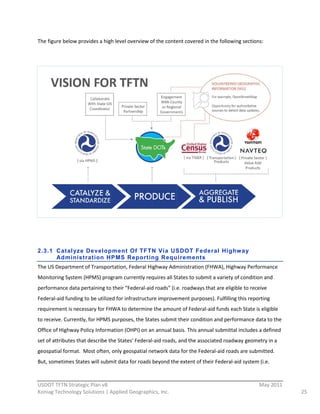

This document provides background on the Transportation for the Nation (TFTN) initiative. TFTN aims to develop comprehensive, publicly available nationwide transportation datasets to address inefficiencies in current overlapping efforts. The current situation sees widespread demand for transportation data but redundancy in creation. A coordinated approach across federal, state and private partners could produce consistent, high quality road centerline data for the entire country in an efficient manner. This strategic plan outlines a vision, goals and requirements to progress TFTN through collaboration and establish a national transportation framework dataset.

![[This page intentionally left blank]

USDOT TFTN Strategic Plan v8 May 2011

Koniag Technology Solutions | Applied Geographics, Inc. 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tftnstrategicplanv8draftfinal-110705182433-phpapp01/85/TFTN-Strategic-Plan-Final-Draft-2-320.jpg)

![[This page intentionally left blank]

USDOT TFTN Strategic Plan v8 May 2011

Koniag Technology Solutions | Applied Geographics, Inc. 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tftnstrategicplanv8draftfinal-110705182433-phpapp01/85/TFTN-Strategic-Plan-Final-Draft-4-320.jpg)