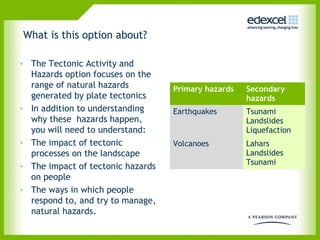

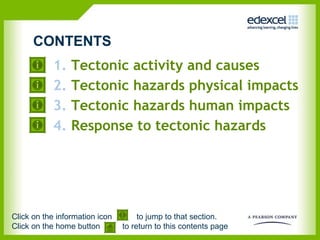

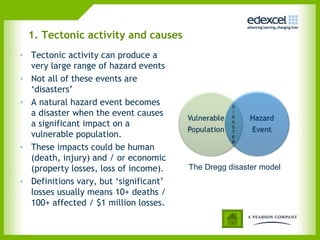

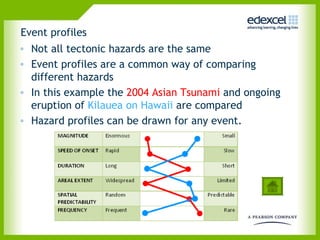

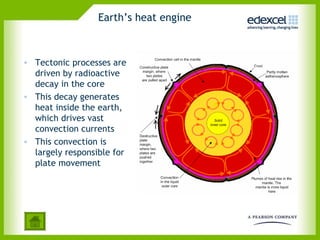

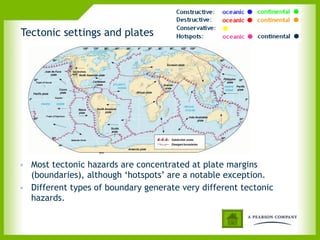

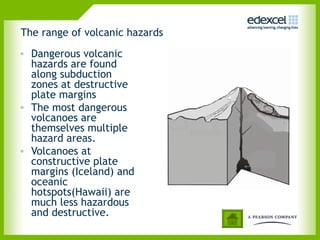

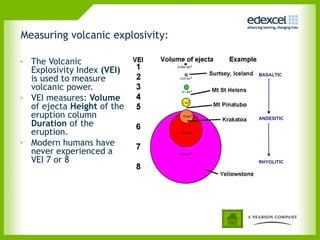

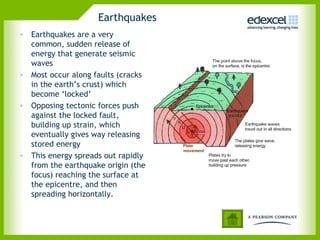

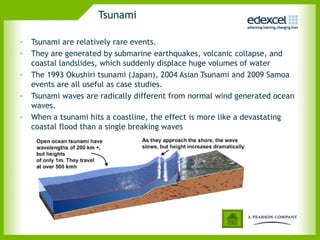

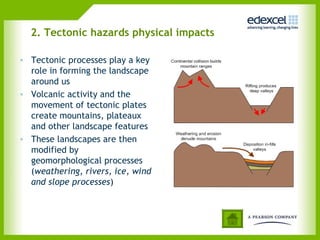

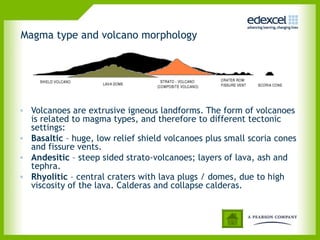

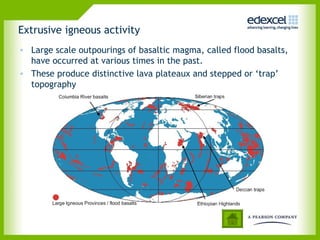

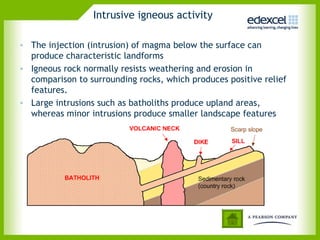

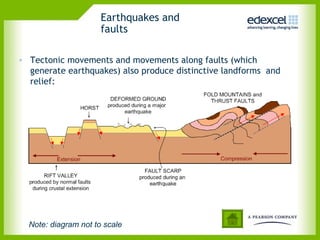

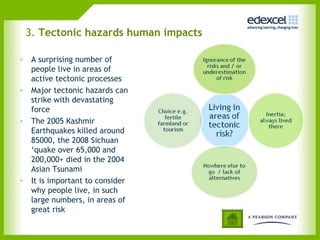

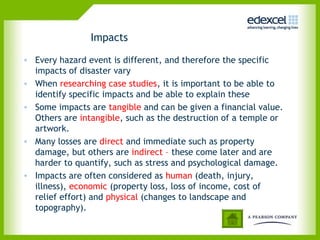

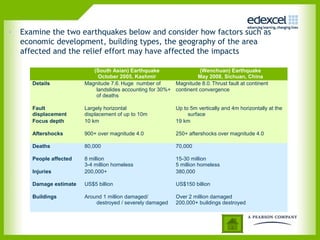

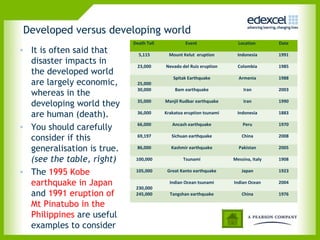

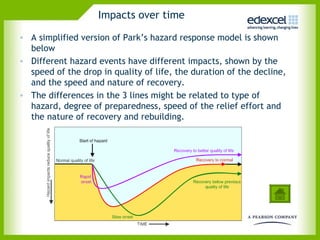

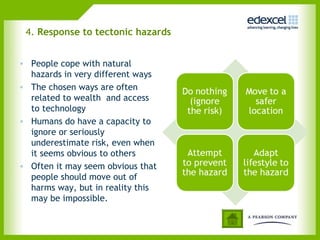

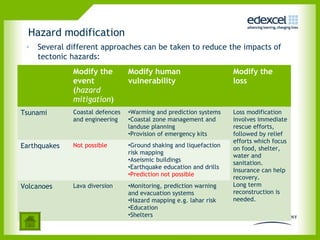

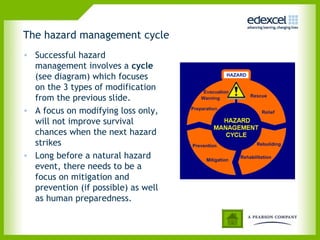

This document provides information about tectonic activity, hazards, and human impacts. It discusses how tectonic processes drive hazards like earthquakes and volcanoes. Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes can have devastating human and economic impacts. The document outlines different response strategies to tectonic hazards, including modifying events, human vulnerability, and losses. Effective hazard management requires ongoing mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery efforts.