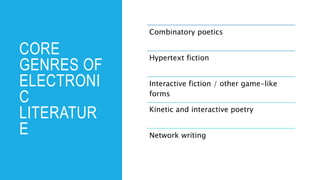

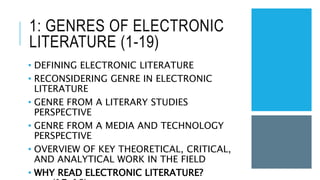

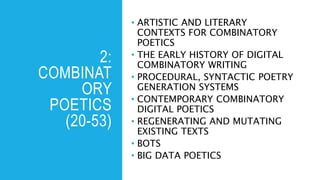

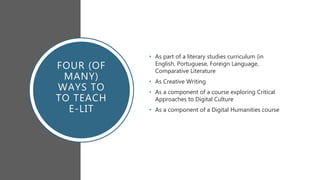

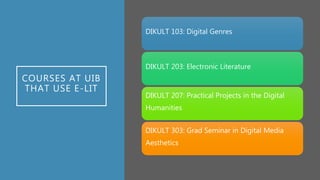

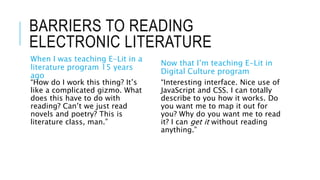

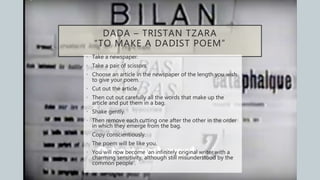

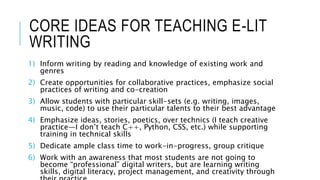

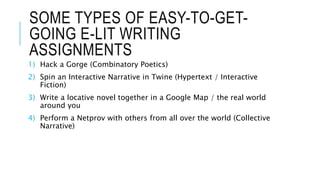

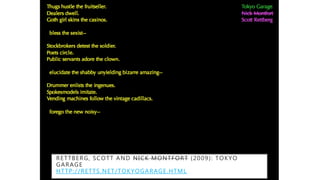

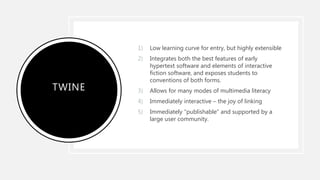

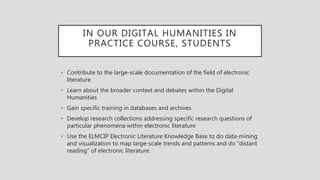

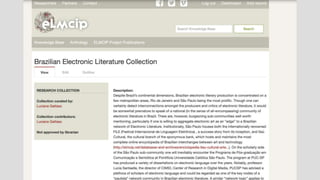

This document provides an overview of Scott Rettberg's talk on teaching electronic literature. It begins by introducing Rettberg and the topic of the talk. The talk aims to provide an overview of Rettberg's new book on electronic literature, share his experiences teaching it, and offer ideas for how it can be taught in different contexts like literary studies, creative writing, and digital humanities. It then discusses barriers to teaching electronic literature and strategies to incorporate it as both literature and creative writing. Specific genres and assignments are discussed as examples.