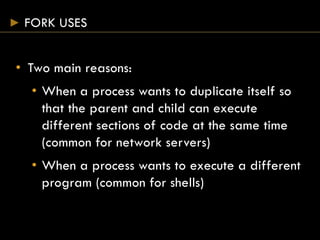

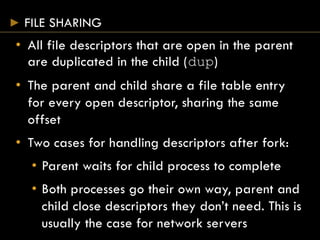

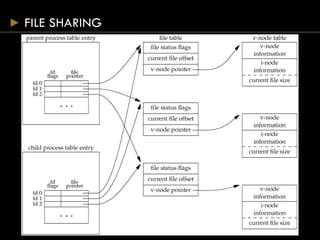

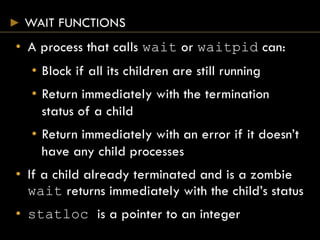

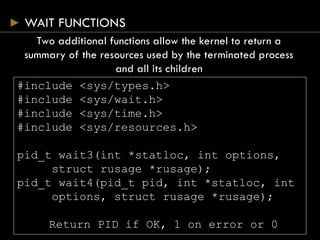

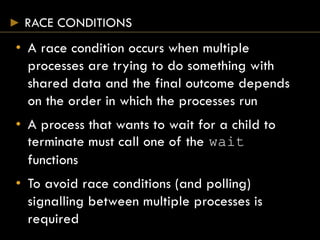

The document discusses essential concepts of processes in Unix systems, covering process identification, startup, termination, resource limits, and memory layout. It explains the fork and exec functions for creating and managing processes, as well as the concepts of file sharing, process groups, and race conditions in concurrent processing. Additionally, it addresses how processes can communicate and manage resources effectively through various function calls.

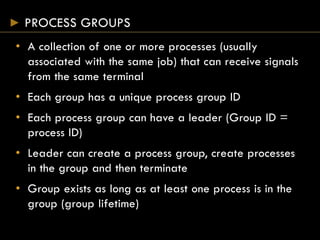

![PROCESS STARTUP AND TERMINATION

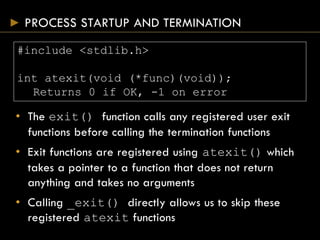

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]);

void exit(int status);

void _exit(int status);

• main() is passed the command line arguments and

should return the termination status

• exit() takes the termination status and causes any

files to be properly closed and memory released

• _exit() terminates the process immediately

closing all file descriptors but not cleanly](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processes-150824075951-lva1-app6892/85/Systems-Programming-Assignment-Help-Processes-4-320.jpg)

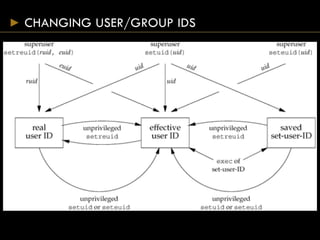

![EXEC FUNCTIONS

#include <unistd.h>

int execl(const char *pathname, const char* arg0

… /* (char *) 0 */);

int execv(const char *pathname, char *const

argv[]);

int execle(const char *pathname, const char

*arg0, … /*(char *) 0, char envp[] */);

int execve(const char *pathname, char *const

argv[], char *const envp[]);

int execlp(const char *filename, const char

*arg0, … /* (char *)0 */);

int execvp(const char *filename, char *const

argv[]);

Return 1 on error, no return on success](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/processes-150824075951-lva1-app6892/85/Systems-Programming-Assignment-Help-Processes-29-320.jpg)