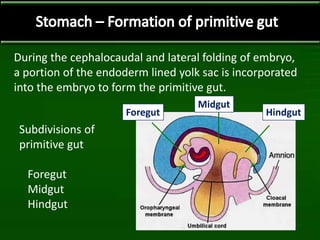

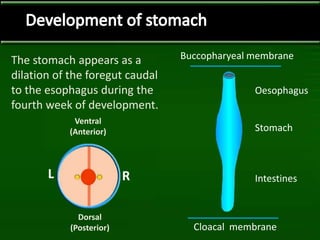

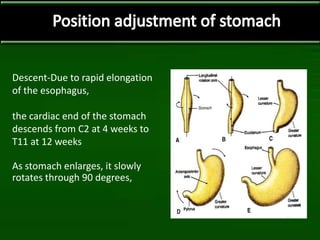

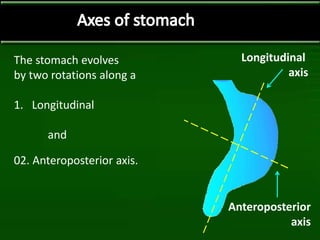

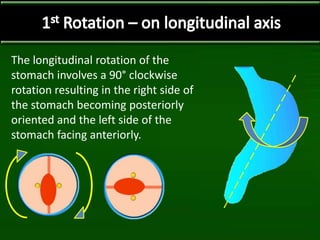

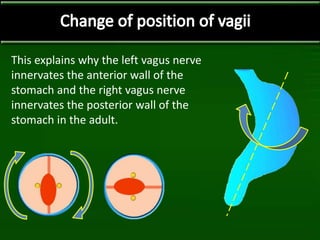

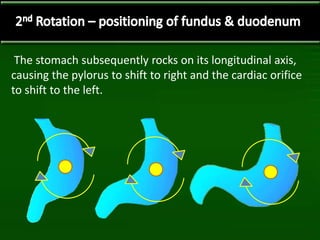

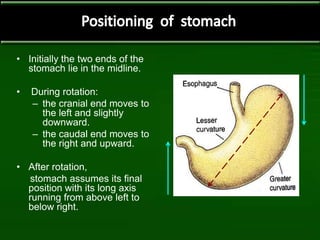

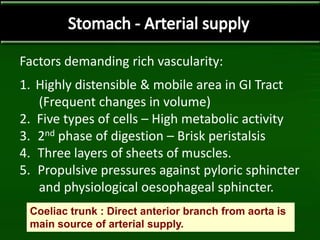

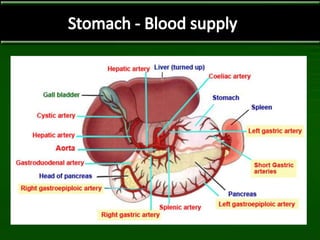

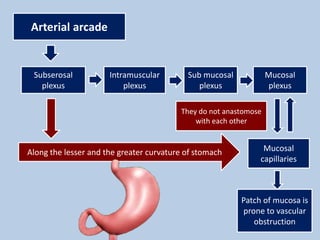

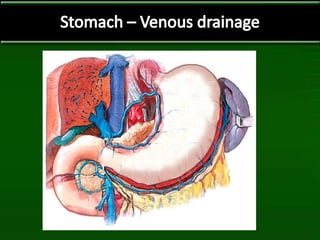

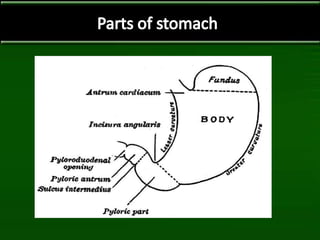

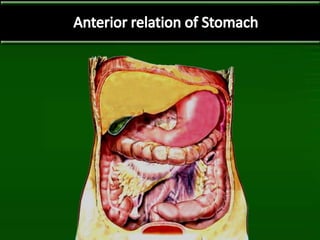

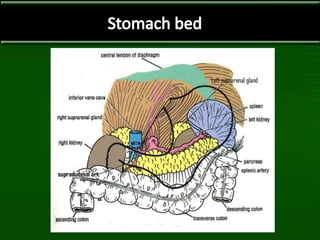

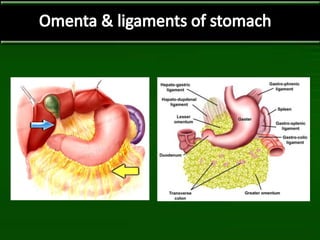

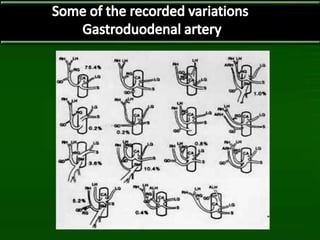

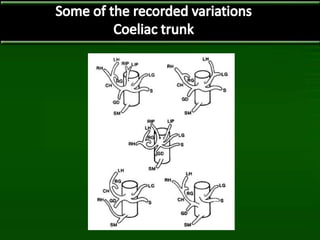

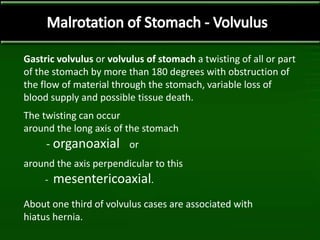

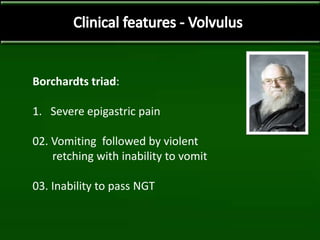

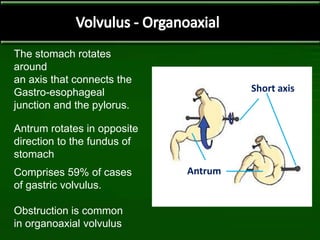

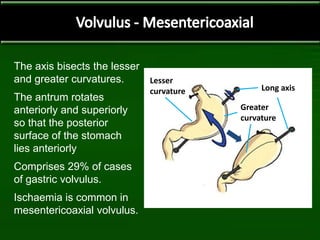

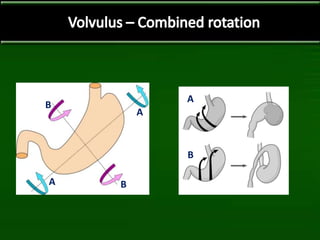

The stomach develops from the foregut during the fourth week of embryonic development. It undergoes two rotations along longitudinal and anteroposterior axes to reach its final adult position. The stomach receives its blood supply from branches of the celiac trunk and develops a complex mucosal and submucosal vascular network. Rare congenital anomalies can affect the shape and rotation of the stomach. Gastric volvulus is a serious condition where the stomach twists around its axes, potentially causing obstruction or ischemia.