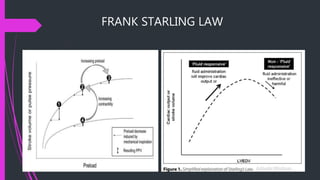

Static parameters of haemodynamic monitoring include central venous pressure, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure, right ventricular end-diastolic volume, left ventricular end-diastolic area, global end-diastolic volume, and intrathoracic blood volume. These parameters are important for guiding fluid therapy and predicting fluid responsiveness, but each have limitations and do not always accurately reflect preload. Next, dynamic parameters will be discussed to better predict the body's response to fluid administration.