This review examined the evidence for using virtual reality (VR) as a therapeutic modality for children with cerebral palsy (CP). A search of 13 databases identified 19 relevant articles, of which 13 studies from 11 articles were included. The studies documented outcomes in domains like brain plasticity, motor capacity, visual-perceptual skills, social participation, and personal factors. Two randomized controlled trials reported conflicting results for motor outcomes. However, 12 of the 13 studies found positive outcomes in at least one domain. The review concluded that VR has potential benefits for children with CP, but the current evidence is poor in methodological quality and empirical data is lacking. More rigorous randomized controlled trials are needed.

![Developmental Neurorehabilitation, April 2010; 13(2): 120–128

SUBJECT REVIEW

Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality for children with

cerebral palsy

LAURIE SNIDER, ANNETTE MAJNEMER, & VASILIKI DARSAKLIS

McGill University, School of Physical & Occupational Therapy, Montreal, Canada

(Received 1 September 2009; accepted 22 September 2009)

Abstract

Objective: The evidence for using virtual reality (VR) with children with cerebral palsy (CP) was examined.

Methods: A search of 13 electronic databases identified all types of studies examining VR as an intervention for children

with CP. The most recent article included was published in October 2008. For each study, the quality of the methods was

assessed using the appropriate scale. A total of 19 articles were retrieved. Thirteen studies from 11 articles were included

in the final analysis.

Results: Outcomes documented brain reorganization/plasticity, motor capacity, visual-perceptual skills, social participation

and personal factors. Two studies were randomized controlled trials. These reported conflicting results regarding motor

outcomes. Twelve of the 13 studies presented positive outcomes in at least one domain.

Conclusions: VR has potential benefits for children with CP. However, the current level of evidence is poor and empirical

data is lacking. Future methodologically rigorous studies are required.

Keywords: virtual reality, cerebral palsy, children

Resumen

Objetivo: Se reviso´ la evidencia sobre el uso de realidad virtual (VR) en nin˜os con para´lisis cerebral.

Me´todos: Una bu´squeda en 13 bases de datos electro´nicas identifico´ todos aquellos estudios respecto al uso de VR como una

intervencio´n para nin˜os por CP: El artı´culo ma´s reciente fue publicado en Octubre de 2008. Para cada estudio, se determino´

la calidad de los me´todos utilizando las escalas adecuadas. Un total de 19 artı´culos fueron recabados. Trece de los 11

artı´culos fueron incluidos en el ana´lisis final.

Resultados: Los resultados documentados fueron reorganizacio´n/plasticidad cerebral, capacidad motriz, habilidad

visuoespaciales, participacio´n social y factores personales. Dos estudios eran ensayos clı´nicos aleatorizados. Estos estudios

arrojaron resultados conflictivos respecto a los resultados motrices. Doce de los trece estudios presentaron resultados

positivos por lo menos en una de las a´reas.

Conclusiones: La realidad virtual tiene efectos potencialmente bene´ficos en nin˜os con para´lisis cerebral. Sin embargo, el

actual nivel de evidencia es pobre y falta informacio´n empı´rica. Se ameritan nuevos estudios metodolo´gicamente estrictos.

Palabras clave: realidad virtual, para´lisis cerebral

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is a virtual environment (VE)

system that uses a range of computer technologies to

present virtual or artificially generated sensory infor-

mation in a format that enables the user to perceive

experiences that are similar to real-life events and

activities [1]. Considering that computer technology

is enticing and intrinsically motivating for children

and adolescents, VR has sparked recent interest as

a new treatment modality for children and youth

with cerebral palsy (CP). CP is a non-progressive

disorder which affects the brain in the early stages

of development, primarily damaging the areas

responsible for the control of movement and pos-

ture [2]. Although no cure is available, therapies,

assistive devices and education are beneficial

in increasing functional independence and partici-

pation [3].

Currently, the popularity of computer technology

among children and adolescents, with or without

Correspondence: Dr Laurie Snider, OT, PhD, McGill University, School of Physical & Occupational Therapy, 3654 Sir-William-Osler Drive, Montreal, H3G

1Y5 Canada. E-mail: laurie.snider@mcgill.ca

ISSN 1751–8423 print/ISSN 1751–8431 online/10/020120–9 ß 2010 Informa UK Ltd.

DOI: 10.3109/17518420903357753](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-1-2048.jpg)

![disabilities, is on the rise, as testified by the docu-

mented increase in use of consumer electronics by

this sub-set of the population [4]. In fact, approx-

imately one in four children own a video game

console, such as the Nintendo Wii or Sony

PlayStation, at home [4]. Consequently, it can be

assumed that children and the youth today are

familiar with this type of technology as it may be

used for leisure and as a method of socialization.

Current VR systems, such as the IREX, are expen-

sive and inaccessible to most of the population [5].

However, interest in commercially available gaming

consoles as a therapeutic medium has been gaining

popularity [6, 7]. Some benefits of technology use

identified by individuals with disabilities are com-

munication with others, the development of social

relationships, as well as the promotion of control,

skill competencies and independence [8].

In rehabilitation, VR is used to create interactive

play environments in order to achieve specific

treatment goals. The primary purpose of VR as a

treatment modality is to improve competence and

confidence in motor-based activities and to engage

in play-based activities that are otherwise inaccessi-

ble in the real world [9, 10]. Virtual environments

can be sub-divided into two types: (1) immersion

VR, which consists of viewing the environment via

screens in a head-mounted display and (2) desktop

VE, which projects the desired image onto a com-

puter or TV screen with sound provided by external

speakers [1]. Tactile feedback (e.g. through a glove)

and force feedback (e.g. resistance in a joystick or

steering wheel) can also be provided in VE [1].

Motor learning theory places great emphasis on the

role of practice and feedback on the development

of proper motor performance as the motor patterns

learned are reinforced through these techniques [9,

11, 12]. VR therapy incorporates fundamental

principles of motor learning theory by allowing the

users to continuously monitor their performance

via a spatial representation of their movements on

the computer screen. With the goal of increasing

functional independence in everyday tasks, VR

provides opportunities for repeated practice and

positive feedback [13]. Users are also informed of

the results of their motor performance (e.g. their

score) through virtual games [9, 12]. Further

advantages include the possibility for the treating

therapist to grade the activities to meet the abilities

of the user as well as to facilitate the exploration of

complex environments that would otherwise be

inaccessible to children with CP due to mobility

restrictions. Early research studies demonstrate that

this modality is feasible, highly enjoyable and

non-threatening [10]. Furthermore there is recent

evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of VR as a

therapeutic intervention for upper limb motor

recovery in adult stroke rehabilitation [14].

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that these results

may be extrapolated to other brain-injured popula-

tions, such as children with CP. This systematic

review seeks to synthesize the available evidence on

this population of interest.

Purpose

To guide future research and clinical intervention,

this study conducted a structured review of the

existing evidence on the therapeutic use of VR with

children with CP. The outcomes investigated in this

review were categorized according to the dimensions

of the International Classification of Functioning,

Disability and Health (ICF): body functions

(e.g. physiological, psychological); structures (e.g.

anatomical); activities (tasks); and participation

(life roles) [15].

Methods

Primary research question

An a priori PICO question was developed to aid

in the search for articles that would comprise this

review [16]: Does training using a play-based VR

intervention improve outcomes (brain reorganiza-

tion/motor skills/spatial skills/motivation and play-

fulness/functional everyday self-care and leisure

activities) in children with cerebral palsy? PICO is

defined as:

. Population: Children with CP;

. Intervention: Virtual games;

. Comparison: Compared to baseline or to a control

group; and

. Outcome: Measures of body structure (fMRI),

body function (motor skills, quality of move-

ments, visual-spatial skills), activity and participa-

tion (self-care and leisure activity performance,

playfulness), personal factors (motivation,

self-perception, self-efficacy).

Systematic review of the literature

The electronic databases MEDLINE: 1950 to week

2, June 2009, PsychINFO: 1806 to week 1, June

2009, CINAHL, ERIC, HealthSTAR: 1966 to May

2009, PEDro, Cochrane database of Systematic

Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled

Trials, CIRRIE, EMBASE: 1980 to week 25, 2009,

Health and Psychosocial Instruments: 1985 to April

2009, OTSeeker and RehabData were searched

using the key words: tetraplegi*, spastic*, quad-

riplegi*, quadrapare*, pes equinus*, monoplegi*,

little* disease, hypotoni*, hemiplegi*, hemipare*,

dystoni*, diplegi*, dyskine*, choreoathe*, atheto*,

Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality 121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-2-2048.jpg)

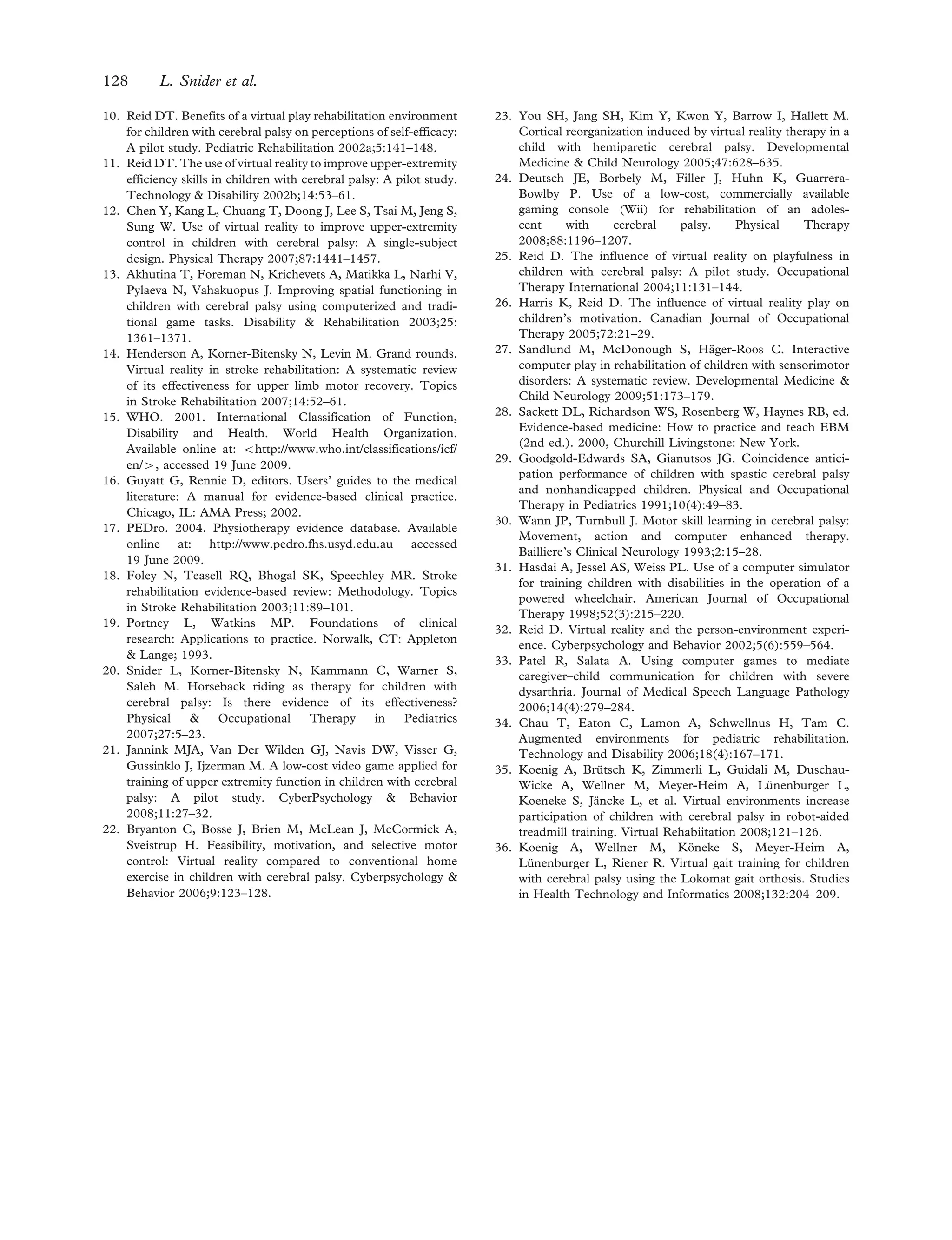

![ataxi*, cerebral palsy, VR, virtual environment,

computer* game* and computer* simulation*.

Only English or French manuscripts were included.

Studies including individuals 18 years of age and

younger as well as all study designs (e.g. randomized

controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental, case

series, case studies) were considered. Articles that

were excluded focused predominantly on individuals

with stroke, traumatic brain injuries, physical dis-

abilities or adults. A total of 13 studies from 11

articles were retrieved for final analysis. A detailed

flowchart of the search strategy and exclusion

process can be found in Figure 1.

Quality assessment

The following information was extracted from each

study: author/date, design, participants, exposure/

intensity, outcomes and significance and ICF com-

ponent assessed. Studies were classified as either

observational or experimental. Experimental studies,

which are higher quality than observational studies,

use comparable control groups, random assignment,

blinding (of assessors, therapists and subjects) and/

or report on subject attrition. The two RCTs

retrieved were rated for methodological quality

using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database

(PEDro) rating scale [17]. According to Foley

Run searches on all relevant

databases and sources

June 2009

Articles

excluded

(n= 521)

Exclusion

criteria

(by title

/abstract)

– Not CP

– Not children

– Not VR

– Duplicates

Total Articles

included

(n= 19)

(Full text

obtained)

Reference

lists

reviewed

and articles

added (n=0)

Articles excluded*: Format (n=4)

Total articles

obtained for

second

screen

(n= 19)

Total articles

considered

eligible after

full-text review

(n= 11)

13 studies from 11 articles included in

the final analysis

Cochrane (SR)

Included: 0

Excluded: 5

PsychInfo

Included: 14

Excluded: 37

Medline

Included: 11

Excluded: 183

OT Seeker

Included: 2

Excluded: 0

RehabData

Included: 2

Excluded: 0

Cochrane (CT)

Included: 1

Excluded: 10

HAPI

Included: 1

Excluded: 0

CINHAL

Included: 11

Excluded: 40

PeDRO

Included: 0

Excluded: 0

ERIC

Included: 1

Excluded: 11

HealthStar

Included: 12

Excluded: 126

Articles excluded*: Population (n=3)

Articles excluded*: Outcomes (n=1)

*see Table III

EMBASE

Included: 12

Excluded:

CIRRIE

Included: 0

Excluded: 0

Figure 1. Flowchart of search strategy and selection process.

122 L. Snider et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-3-2048.jpg)

![et al.’s [18] quality assessment, studies scoring 9–10

on the PEDro scale are considered to be method-

ologically ‘Excellent’, 6–8 ‘Good’, 4–5 ‘Fair’ and

below 4 ‘Poor’. Observational study designs

included in this review consist of quasi-experimental

or descriptive pre–post designs [19]. These designs

do not include randomization and, in some cases,

subjects act as their own controls. Level of evidence

ratings are based upon a modified Sackett score

adapted to include PEDro ratings (see Table I) [28].

These levels have been described in greater detail

in other work by Snider et al. [20].

Results

Study characteristics

The data extracted from the 13 eligible studies is

summarized in Table II. A summary of excluded

articles is found in Table III.

Categorization according to ICF components

In children with CP, is VR therapy more effective than

no intervention, placebo intervention, or an alternative

intervention for body functions and body structure

outcomes?

One ‘good’ pilot RCT involving 31 children with CP

investigated this question; however, no significant

results were yielded [9]. One ‘fair’ exploratory RCT

with a sample size of 10 children revealed that scores

on the Melbourne Assessment of Unilateral Upper

Limb Function either improved or stayed the same

in the experimental group. The highest percentage

change between pre- and post-test coincided with

the results of two children from the experimental

group [21].

One quasi-experimental study consisting of 45

children found that visual-spatial abilities in the

treatment group improved more compared to the

control group [13]. In another quasi-experimental

study of 21 children conducted by the same authors,

no difference in the spatial functioning between

the control and experimental groups was found [13].

In an observational study investigating the kinemat-

ics of ankle dorsiflexion during VR therapy as

compared to conventional exercises, it was found

that more repetitions were completed when follow-

ing a conventional exercise programme. Children

also required more time to complete one set of VR

exercises. However, on average, a longer hold time

for VR exercises as well as a greater mean for ankle

dorsiflexion ankle range of motion was noted during

VR exercises [22]. A single-subject design study

investigated the reaching kinematics and fine motor

abilities of four children between the ages of 4–8

years with CP. Descriptive analysis of the results

revealed that 75% of the children showed qualitative

improvement in the reaching kinematics, which

was partially maintained 4 weeks post-treatment.

Fine motor scores improved for all children and 75%

of the children showed increased scores on the

visual-motor integration sub-test of the Peabody

Developmental Motor Scales–2nd edition [12].

Three case studies have also been published

addressing this question. One revealed improved

scores on the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor

Proficiency accuracy score; however, no consistent

effect in the quality of upper extremity movements

was detected [11]. Another study indicated

improved quality of movement of the affected

upper limb as well as a greater activation of the

contralateral sensorimotor cortex [23]. In the last

case study, it was found that following VR therapy,

visual-perceptual processing improved, as well as

postural control, weight distribution and functional

mobility [24]. In summary, there is conflicting

evidence (primarily Level 4) that VR therapy is

effective in enhancing body structures or functions

when compared to traditional or no intervention.

However, the results from both RCTs are prelimi-

nary and the remaining evidence originates from

Table I. Levels of evidence (adapted from Sackett).

Level Description

1a (Strong) Well designed Meta-Analysis or two or more ‘high’ quality RCT’s (PEDro ! 6) showing similar findings

1b (Moderate) 1 RCT of ‘high’ quality (PEDro ! 6)

2a (Limited) At least 1 ‘fair’ quality RCT (PEDro ¼ 4–5)

2b (Limited) At least one ‘poor’ quality RCT (PEDro 5 4) or well-designed non-experimental study (non-randomized

controlled trial, quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies with multiple baselines, single subject series with

multiple baselines, etc.)

3 (Consensus) Agreement by an expert panel or a group of professionals in the field or a number of pre–post studies all with

similar results

4 (Conflict) Conflicting evidence of two or more equally well designed studies

5 (No evidence) No well-designed studies—only case studies/case descriptions or cohort studies/single subject series with no

multiple baselines)

Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality 123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-4-2048.jpg)

![TableII.Summaryofstudiesonvirtualreality.

Reference

Subjects;samplesize;

agerangeMethodologyOutcomemeasures/Variables*Mainfindings

[10]Spasticquadriplegiaor

diplegia;n¼3;8–12

years

Casestudy,pre/posttest

design,two90minute

sessionsperweek,

4weeks

CanadianOccupationalPerformance

Measure(COPM)—mainlyself-care

andleisureactivitieswereidentified

Performanceandsatisfactionscoreswereratedhigheratpost-test

forallparticipants(clinicallysignificant).

Suggestsbeneficialeffectswithrespecttoself-efficacy.Descriptive

analysis&graphicpresentation.

[11]Spasticquadriplegiaor

diplegia;n¼4;8–12

years

Casestudy,pre/posttest

design;1.5hours/week,

8weeks

QualityofUpperExtremitySkillsTest

(QUEST),BOTMP(item6of

sub-test5—motoraccuracy)

ScoresimprovedontheBOTMPaccuracyscore.

Changeinqualityofupperextremitymovementswasvariable

(noconsistenteffect).

Descriptiveanalysis.

[13]Cerebralpalsy;n¼21;

7–14years;

12experimental,9control

Experimentaldesign;

30–60min/session,

6–8Âovera1month

period

Computer-based:KoosBlockDesignTest,

ClownAssemblyTestOthertests:

DecentrationofViewpointTest,

DirectionalPointingtoHiddenObject

Test,RavenProgressiveMatrices,

BentonJudgmentofLineOrientation

Test,Arrowssub-testofthe

NeuropsychologicalTestBatteryfor

Children,RoadsTest

Nosignificantchangeswereobserved(mostchildreninexperimental

groupwerenon-ambulatorywhereasmostcontrolswereambula-

tory).Descriptive&comparativestatistics(t-test;Chi-square).

Cerebralpalsy(mostdiple-

gia);n¼45;agenotspeci-

fied;23experimental,

22control

Experimentaldesign;

30–60min/session,

6–8Âovera1month

period

Visual-spatialabilitiesofthechildreninthetreatmentgroup

improvedmorecomparedtothecontrolgroup.

Descriptive&comparativestatistics(t-test,chi-square,ANOVA).

[25]Cerebralpalsy;n¼13;

8–12years

Observationalstudy

(videotapeanalysis)

81-hoursessions

TestofPlayfulnessChildrenexhibitedallelementsofplayfulness(intrinsicmotivation,

internalcontrol,suspensionofrealityandframing)whileplaying

theVRgames.

Playfulnessvariedwiththetypeofvirtualenvironment,somebeing

moreengagingthanothers.Descriptive&qualitativeanalysis.

[26]Cerebralpalsy;n¼16;

8–12years

Observationalstudy

(videotapeanalysis)

1hour/week,8weeks

PediatricVolitionalQuestionnaire

(measuresmotivation,levelof

engagement)

VRplayisamotivatingactivity,thereforeofinterestasaninterven-

tiontool.

Levelofvolitionwasinfluencedbythetypeofvirtualenvironment

(e.g.degreeofvariationinthegame,degreeofchallenge,

competition).Descriptive&qualitativeanalysis.

[23]Hemiplegia;n¼1;8yearsCasestudy;

60min/day,5Â/week

for4weeks

fMRI,BOTMP,modifiedPediatric

MotorActivityLogQuestionnaire,

UpperLimbsub-testofthe

Fugl-Meyerassessment

Improvedfunctionalmotorskills(use)andbetterqualityofmove-

ment(control,coordination)inaffectedupperlimb.

Post-intervention,spontaneousreaching,self-feedinganddressing

werenoted(notpossiblepriortoVR).

Concurrently,therewasgreateractivationofthecontralateral

sensorimotorcortex(asopposedtoipsilateralorbilateral).

Descriptivestatistics.

[9]Cerebralpalsy;n¼31;

8–12years;

19experimental,12control

(standardcare)

Randomizedcontrolled

trial;1.5hours/week,

8weeks

CanadianOccupationalPerformance

Measure(COPM),QualityofUpper

ExtremitySkillsTest(QUEST),

HarterSelf-PerceptionProfilefor

Children(SPPC)

Significantlyincreasedscoresforthesocialacceptancesub-scale

favouringtheexperimentalgroup.

VRappearstoincreasemotivationinexperimentalgroup.

Manychildreninthecontrolgroupwerelosttofollow-up.

Descriptive&comparativestatistics(t-test).

124 L. Snider et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-5-2048.jpg)

![[22]Cerebralpalsyandother;

n¼10withcerebral

palsy,n¼6without

cerebralpalsy

Observationalstudy;

One90minsession

Ankledorsiflexionexercises

alternatedbetweenVR

andconventionalexer-

cises(AB-BAdesignfor

intervention

administration)

VisualAnalogueScaleregardinginterest/

perceptionoffun(parentsand

children)

Movementkinematicsvia

electrogoniometer

Childrenandparentsreportedhigherlevelsoffunandinterest

withVR.

Morerepetitionscompletedwithconventionalexercises.

LongeraveragetimetocompleteonsetofVRexercise.

LongerholdtimesforVRexercises.

GreatermeanankledorsiflexionanklerangeofmotioninVR

exercises.

VRexercisesgoal-oriented.Descriptiveanalysis&graphic

representation.

[12]Spasticcerebralpalsy;

n¼4;4–8years

Single-subjectdesign,AB

with2-4weekfollow-up;

2hours/week,4weeks

Reachingkinematics,FineMotor

DomainofPDMS-2(sub-tests:

grasping,visual-motorintegration)

3/4childrenshowedimprovementinsomeaspectsofqualityof

reachingwhichwaspartiallymaintained4weeksaftertreatment.

ScoresonthePDMS-2increased(1–11points)forallchildren;

scoresonthevisual-motorintegrationsub-testimprovedfor3/4

subjects.Descriptiveanalysis;Statisticalanalysisofsinglesubject

designs(Cstatistic).

[24]Spasticdiplegia;n¼1;

13years

Casereport;

11sessions60–90minutes

(twogroupsessions)

4weeks

Inadditiontoregular

therapies

QUEST,GMFM,TVPS-3,Posture

ScaleAnalysr,Retrospectivedata

fromchartreview

Visualperceptualprocessing:Improvementinalldomainssequential

memory.Gainsmaderangefrom4–70percentilechanges.

Posturalcontrol:greaterloadingonLE;decreasedposturalsway

by60%;moresymmetricaldistributionofmedial-lateralweight.

Functionalmobility:increasedby235ft.Descriptiveanalysis.

[21]Spasticcerebralpalsy;

n¼12;7–16years

Casereport;treatment

duration&intensitynot

specified

QuestionnairedevelopedIntuitivetouse.

ChildrenweremotivatedtotrainusingtheEyeToy.

Descriptiveanalysis.

Spasticcerebralpalsy;

n¼10;7–16years

Randomizedtrial;

30minutes2Â/week6

weeks

MelbourneAssessmentofUnilateral

UpperLimbFunction

Increaseinscorefor6/10subjects;2nochange,2loss.Highest%

changein2childrenfromexperimentalgroup(9%and13%).

Descriptiveanalysis.

ANOVA:AnalysisofVariance;BOTMP:Bruininsks-OseretskyTestofMotorProficiency;fMRI:functionalMagneticResonanceImaging;PDMS-2:PeabodyDevelopmentalMotorScales-2;

GMFM:GrossMotorFunctionalMeasure;TVPS-3:TestofVisualPerception-3;LE:LowerExtremity.

Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality 125](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-6-2048.jpg)

![lower quality studies. Further research of higher

methodological rigour is required.

In children with CP, is VR therapy more effective than

no intervention, placebo intervention or an alternative

intervention for activity and participation outcomes?

One ‘good’ pilot RCT revealed no significant

differences in the Canadian Occupational

Performance Measure performance and satisfaction

scores [9]. One observational study of 13 children

with CP indicated the all the children exhibited the

elements of playfulness while engaged in VR games.

The degree of playfulness fluctuated with the type of

virtual environment that was provided [25]. A case

study reporting on this question revealed that chil-

dren participated in self-feeding and dressing

post-intervention, activities that had not been pos-

sible or observed prior to VR therapy [23]. In

summary, there was a moderate level of evidence

(Level 1b) to suggest that VR therapy does not have

a positive impact on activity and participation

outcomes when compared to no intervention or

traditional therapy. Nevertheless, two other studies

of lower level of evidence indicate results to the

contrary. As the results generated by all the studies

with respect to this question are preliminary and

originate from small sample sizes, more research in

this area is warranted.

In children with CP, is VR therapy more effective than no

intervention, placebo intervention or an alternative

intervention for personal factor outcomes?

One ‘good’ pilot RCT revealed a significant increase

in scores for the social acceptance sub-scale of the

Harter Self-Perception Profile for Children in the

group receiving VR therapy. It was also found to

have a positive impact on the children’s motivation

[9]. Two observational studies reported on higher

levels of enjoyment and interest in participants

following VR therapy [22]. The type of VE that the

children are exposed to influenced their level of

volition [26]. Two case studies have reported higher

performance and satisfaction scores [10] as well as

greater levels of motivation to train with VE [21].

In summary, there is a moderate level (1b) of evi-

dence to suggest that VR therapy has a positive effect

on personal factors such as motivation, volition and

perceptions of self-efficacy as compared to no inter-

vention or alternative treatment methods. The

results of the RCT are supported by the outcomes

measured from several lower quality studies.

Discussion

VR therapy still remains a relatively new intervention

modality and the preliminary research in this

area is just emerging (publications since 2002).

Considering the novelty of this therapeutic modality,

the current evidence stems primarily from observa-

tional studies and case reports. Consequently, this

structured review included all types of research

design. Early evidence suggests that VR therapy

can be an effective and motivating therapeutic

modality for children with CP. In fact, of the nine

studies included in this review examining brain

reorganization, motor skills or visual-spatial out-

comes, seven indicated positive results in this area.

Of the three studies reporting on activity and

participation, two lower level studies indicated ben-

eficial effects in this domain. Finally, five studies

investigating the impact of VR on personal factors

were unanimous in determining that VR therapy had

a positive impact.

The potential uses of VR are vast, yet validation

of findings is necessary as the current body of

research is dominated by lower quality of evidence.

Table III. Summary of excluded articles.

Author(s) Title

Goodgold-Edwards SA, Gianutsos JG (1990) [29] Coincidence anticipation performance of children with spastic cerebral palsy and

non-handicapped children

Wann JP, Turnbull JD (1993) [30] Motor skill learning in cerebral palsy: movement, action and computer-enhanced

therapy

Hasdai A, Jessel AS, Weiss PL (1997) [31] Use of a computer simulator for training children with disabilities in the operation

of a powered wheelchair

Reid D (2002) [32] Virtual reality and the person-environment experience

Patel R, Salata A (2006) [33] Using computer games to mediate caregiver–child communication for children

with severe dysarthria

Chau T, Eaton C, Lamon A, Schwellnus H, Tam C (2006)

[34]

Augmented environments for paediatric rehabilitation

Koenig A, Bru¨tsch K, Zimmerli L, Guidali M, Duschau-

Wicke A, Wellner M, Meyer-Heim A, Lu¨nenburger L,

Koeneke S, Ja¨ncke L, et al. (2008) [35]

Virtual environments increase participation of children with cerebral palsy in

robot-aided treadmill training

Koenig A, Wellner M, Ko¨neke S, Meyer-Heim A,

Lu¨nenburger L, Riener R (2008) [36]

Virtual gait training for children with cerebral palsy using the Lokomat gait

orthosis

126 L. Snider et al.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-7-2048.jpg)

![Several threats to internal validity can explain the

findings of improvements in outcome measures

(e.g. practice effect and lack of blinded evaluators).

Duration of treatment in the studies included in this

structured review varied greatly, as did the choice

of outcome measures. All studies included in this

review had small sample sizes, which limited the

extent to which results could be generalized.

Furthermore, in the experimental studies, discre-

pancies at baseline between the control and inter-

vention groups were not always considered, which

can impact on the outcomes assessed. The great

variability in the assessments used to measure the

outcomes makes it difficult to synthesize results.

Use of more responsive measures will improve the

detection of changes in outcomes [27]. The majority

of studies investigating VR therapy utilized high cost

systems that many clinical facilities do not have the

means to purchase [5]. Considering that VR therapy

is motivating and engaging, it can be hypothesized

that compliance to treatment would be high. This is

further supported by promising positive results from

albeit low quality studies investigating commercially

available systems [21, 24]. These results demon-

strate the need for further research on readily

available gaming systems and their benefits for this

population.

Although outcomes were not specifically categor-

ized by authors according to the dimensions of the

ICF, the majority of outcomes measured were

related to body structures and function as well as

activity and participation. Specifically, there were far

fewer studies related to activity and participation.

Further investigations should be initiated in this

domain, particularly as VR may be useful to promote

social participation through virtual environments as

the barriers that are present in natural environments

can be eliminated.

Conclusion

Currently, there is a paucity of well designed studies

investigating the benefits of VR therapy in the

rehabilitation of children with CP. Overall, the

level of evidence is poor, as most of the studies are

experimental and observational studies with small

sample sizes. The results of this systematic review

reveal that there is conflicting evidence (Level 4) that

VR therapy has positive effects on body structures

and functions, a moderate level of evidence (Level

1b) that VR does not positively impact on activity

and participation and a moderate level of evidence

(Level 1b) that VR therapy positively impacts on

personal factors such as motivation, volition and

interest.

With the Wii and other games gaining popularity in

rehabilitation settings across North America,

research regarding commercially available gaming

systems is an emerging interest in this field, as the

potential benefits of this treatment modality seem

promising [6, 7]. As children with CP are a hetero-

geneous group, it would be necessary to clarify the

sub-groups of the population that would most benefit

(age, gender, type of CP, motor abilities, cognitive

function, etc.) and what treatment outcomes should

be targeted. The long-term benefits of VR therapy

are still unknown. More high quality randomized

controlled trials on large samples with follow-up are

needed to ascertain for which children with CP and

for what outcomes this approach may be better

than traditional rehabilitation interventions.

Acknowledgements

This review was conducted as part of a presentation

on occupational therapy intervention for cerebral

palsy consensus meeting, September 2008, Oxford,

United Kingdom. The authors are members of the

Research Institute of the McGill University Health

Centre, which is supported in part by the Fonds de

recherche´ en sante´ du Que´bec. This study was

initially funded by an operating grant from the

Reseau provincial de recherche en adaptation-

re´adaptation.

Declaration of interest: The author reports no

conflict of interest. The author alone is solely

responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

1. Wilson PN, Foreman N, Stanton D. Virtual reality, disability

and rehabilitation. Disability & Rehabilitation 1997;19:

213–220.

2. Bax M. Terminology and classification of cerebral palsy.

Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1964;6:

295–296.

3. Yamamoto MS. Cerebral palsy. In: Hansen RA, Atchison B,

editors. Conditions in occupational therapy: Effect on occu-

pational performance. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p 8–15.

4. Riley DM. Kids’ use of consumer electronics devices such as

cell phones, personal computers and video game platforms

continue to rise. Port Washington, NY: NPD Group, Inc.;

2009.

5. Reid D. Virtual reality and the person-environment experi-

ence. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 2002;5:559–564.

6. Associated Press. La Wii comme the´rapie. La Presse;

17 February 2008, Associated Press: Montreal, QC.

7. Kutlu N. La ‘Wii the´rapie’ fait son chemin au Que´bec.

La Presse; 17 February 2008: Montreal, QC.

8. Lupton D, Seymour W. Technology, selfhood and physical

disability. Social Science & Medicine 2000;50:1851–1862.

9. Reid D, Campbell K. The use of virtual reality with children

with cerebral palsy: A pilot randomized trial. Therapeutic

Recreation Journal 2006;40:255–268.

Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality 127](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virtualrealityasatherapeuticmodalityforchildrenwith-170619015915/75/slide-8-2048.jpg)