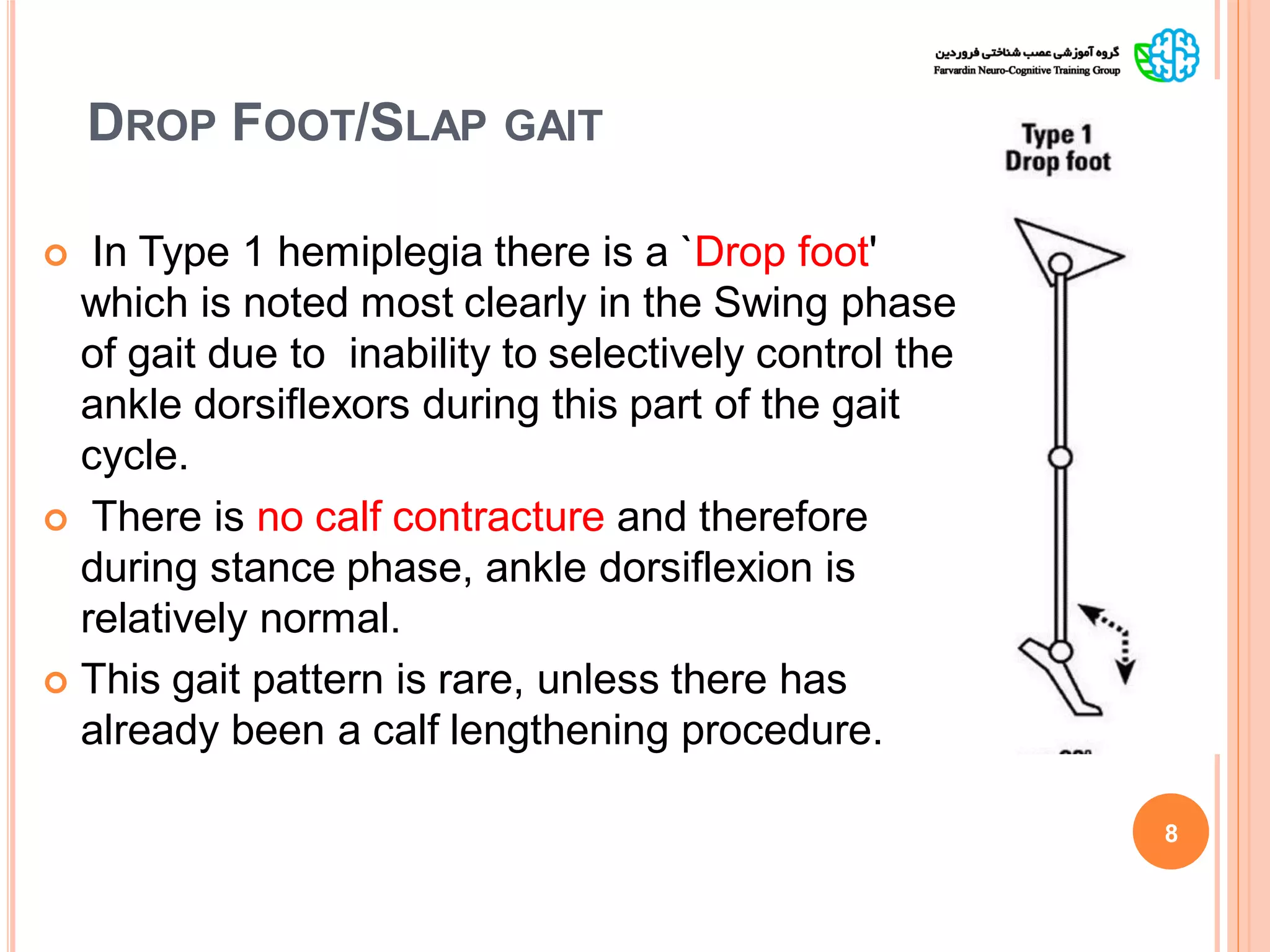

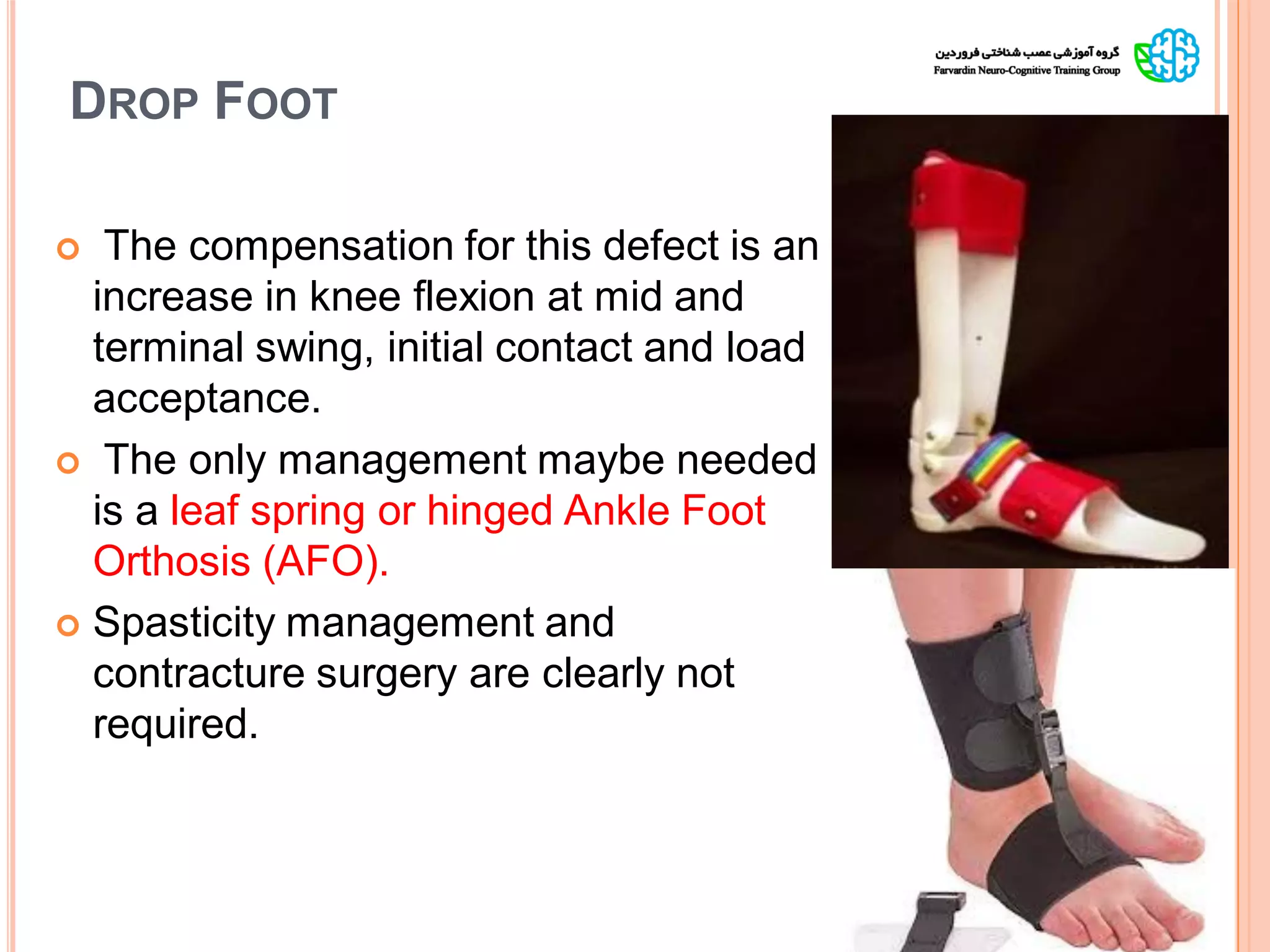

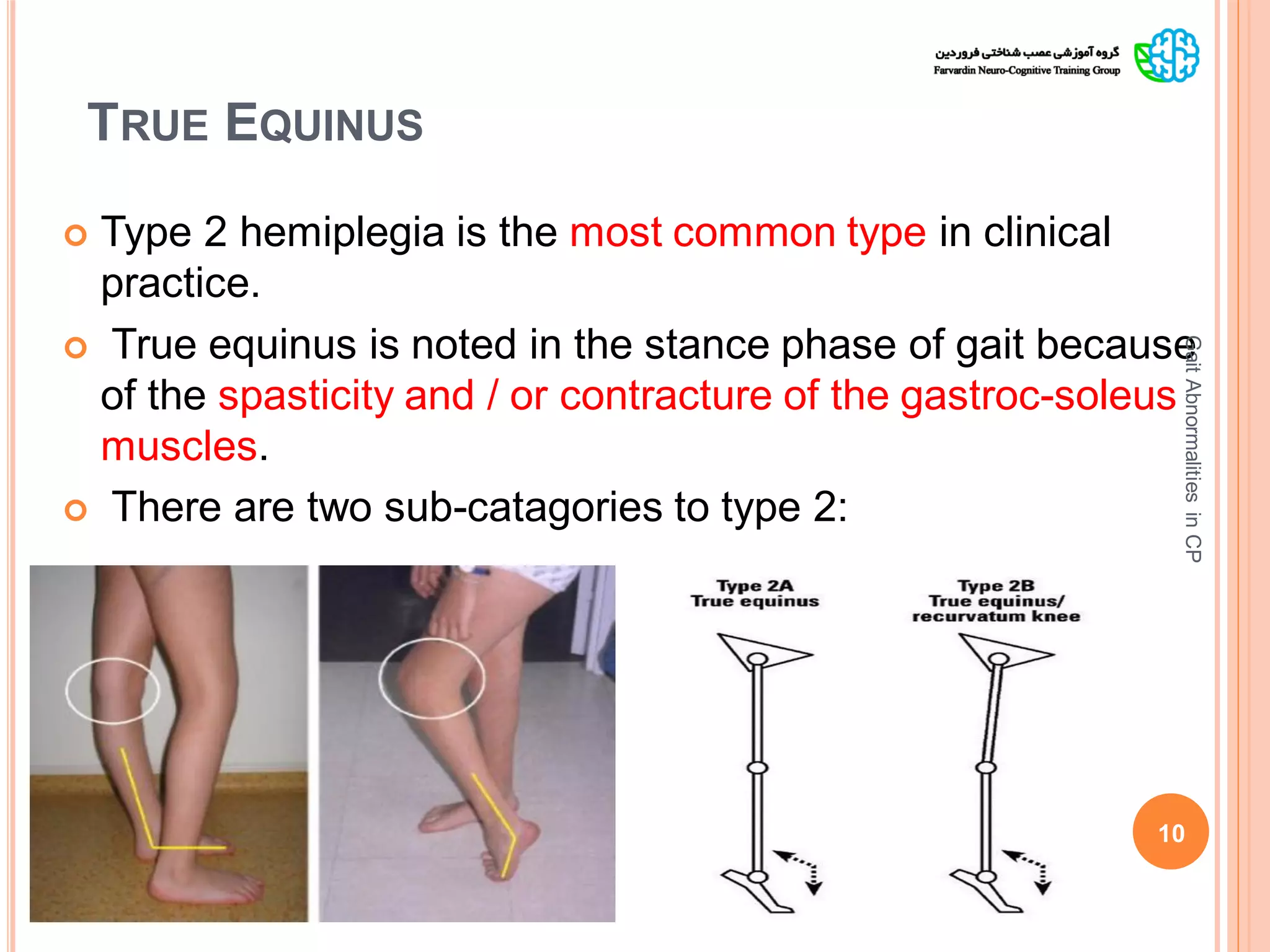

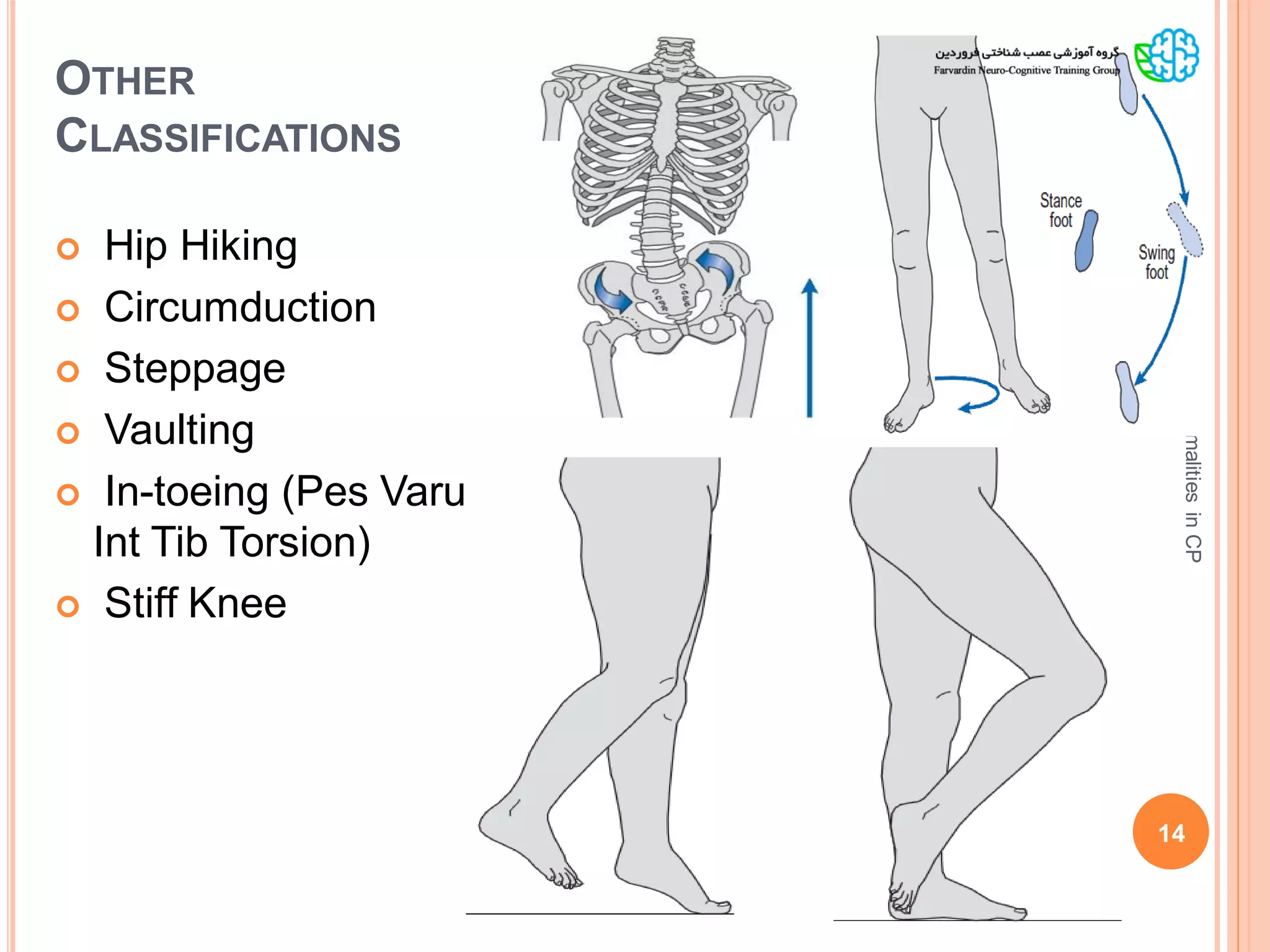

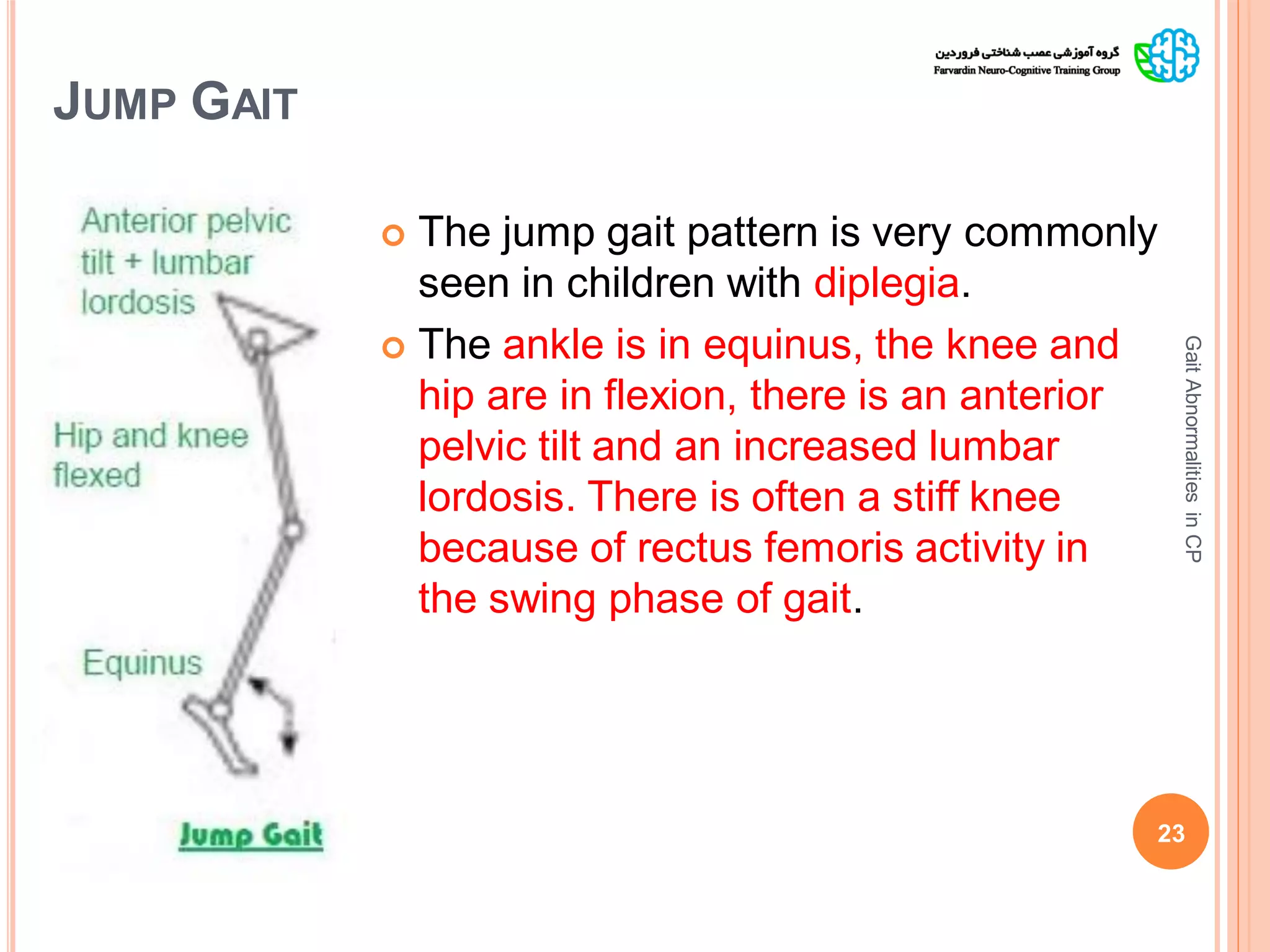

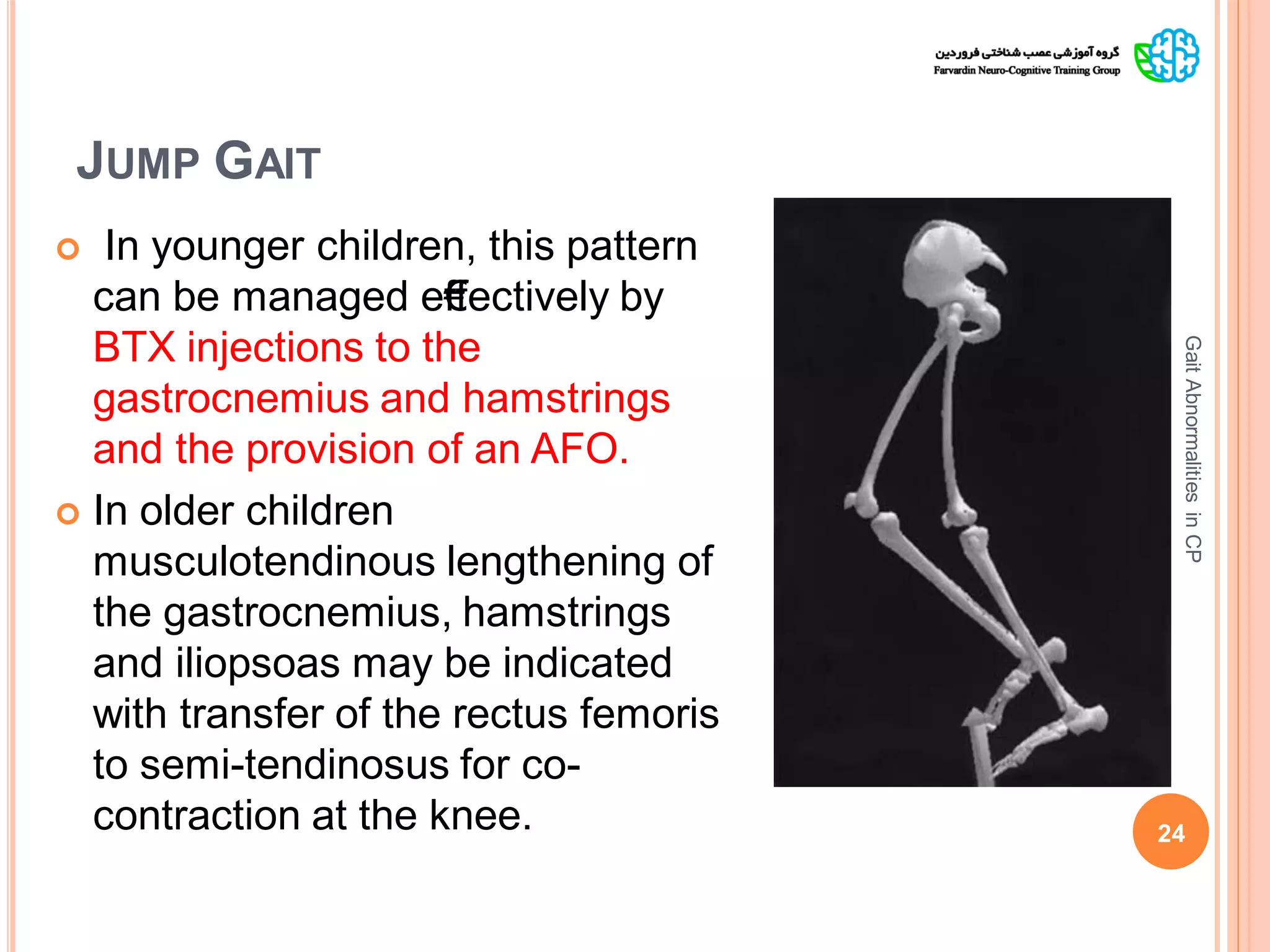

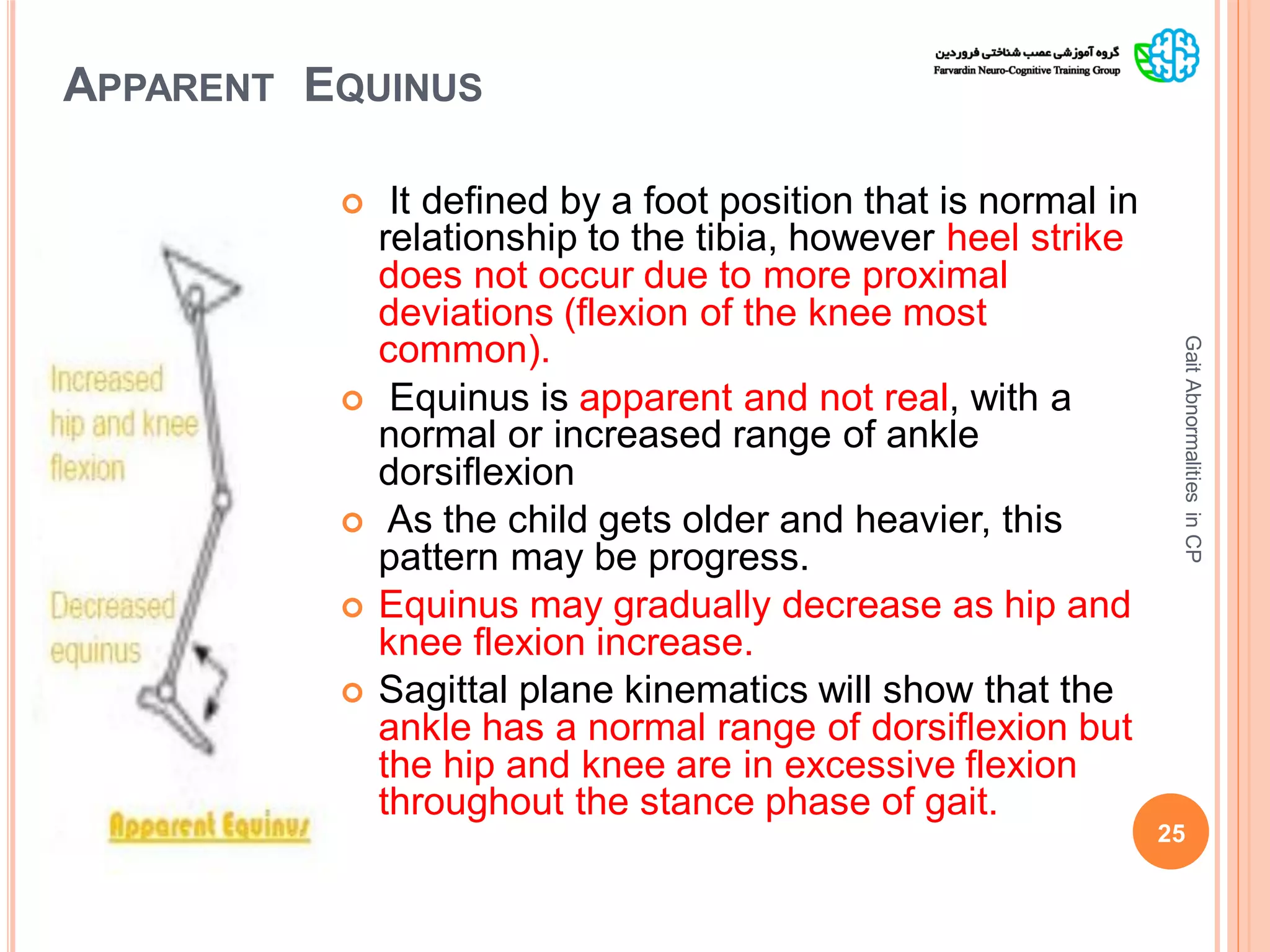

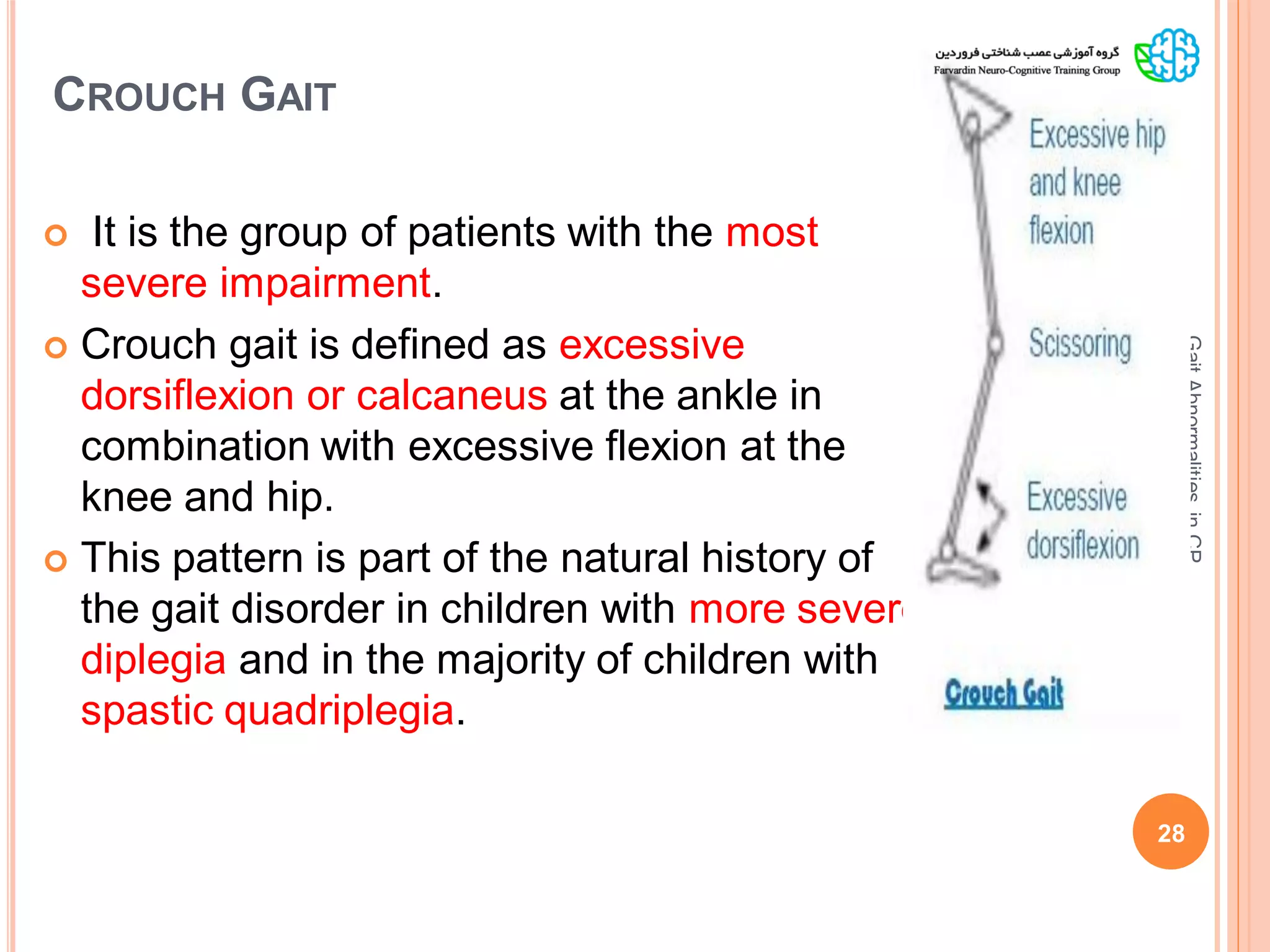

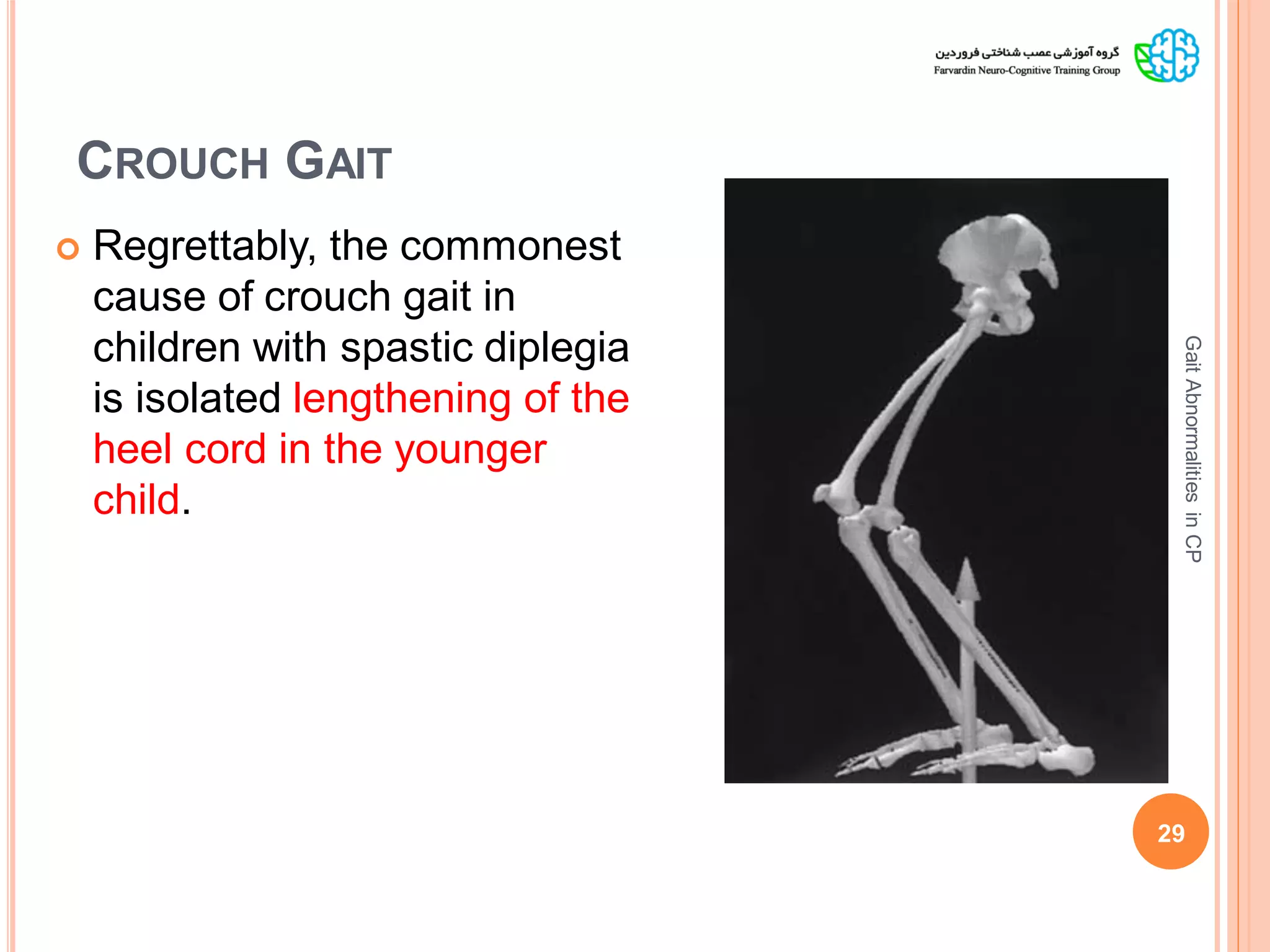

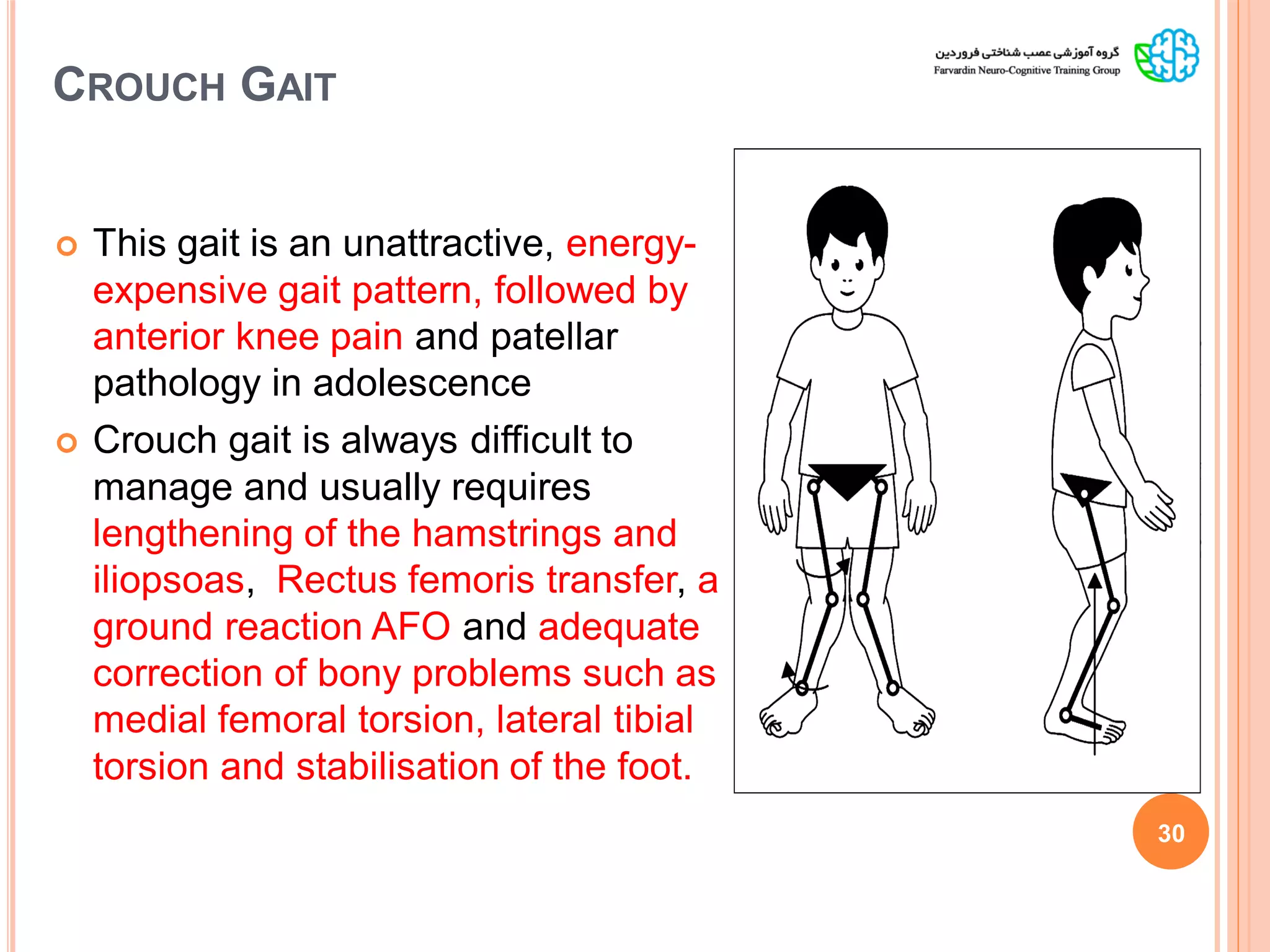

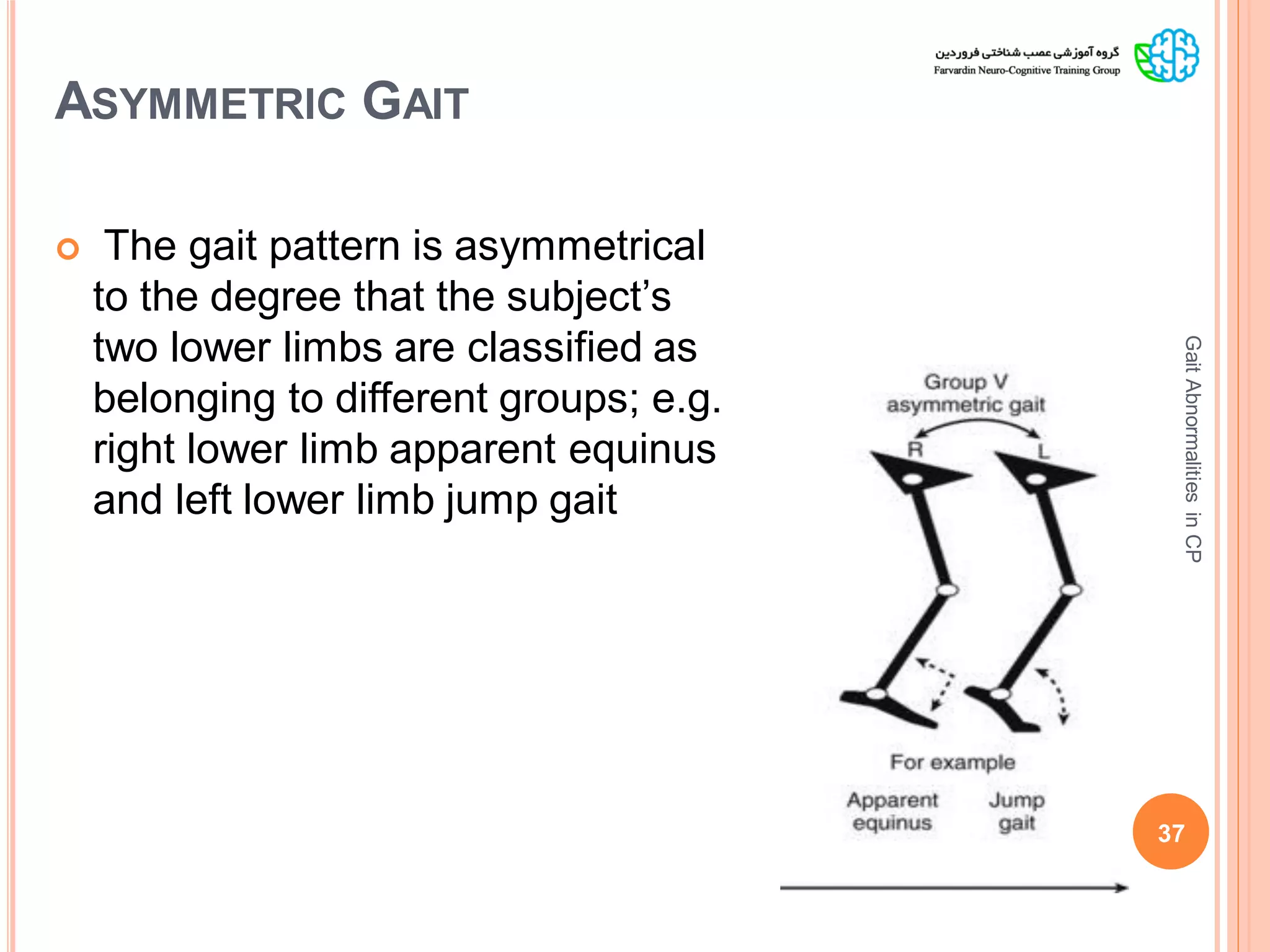

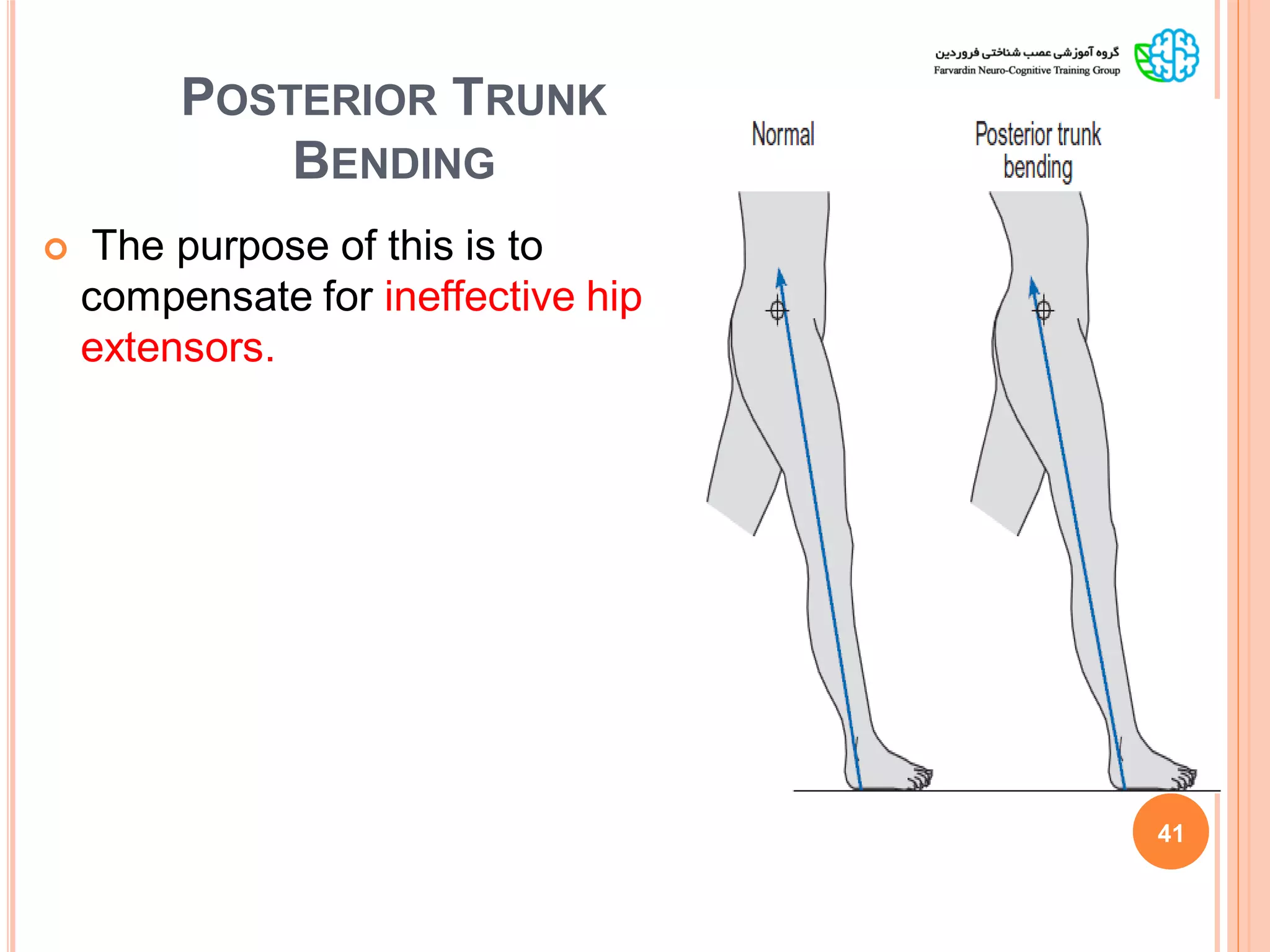

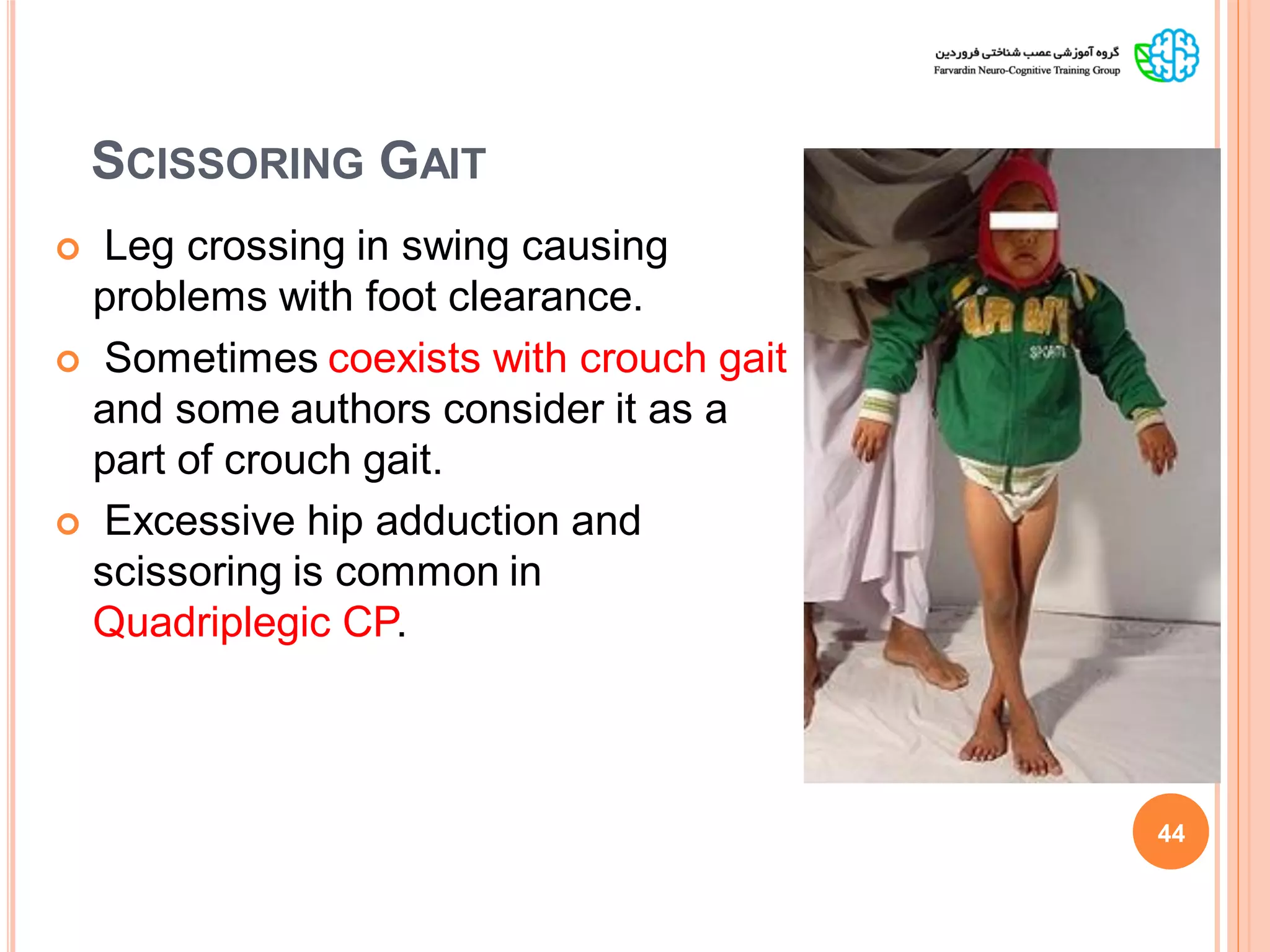

The document presents a comprehensive analysis of gait pattern classification in children with cerebral palsy (CP), discussing various abnormalities and classifications based on the type of hemiplegia and underlying neuromuscular deficits. It highlights the importance of gait analysis and clinical evaluations in understanding the primary and compensatory strategies affecting gait, as well as outlines management and treatment protocols for different gait patterns observed in these children. The document serves as a guide for clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis and intervention strategies for gait abnormalities in pediatric patients with CP.