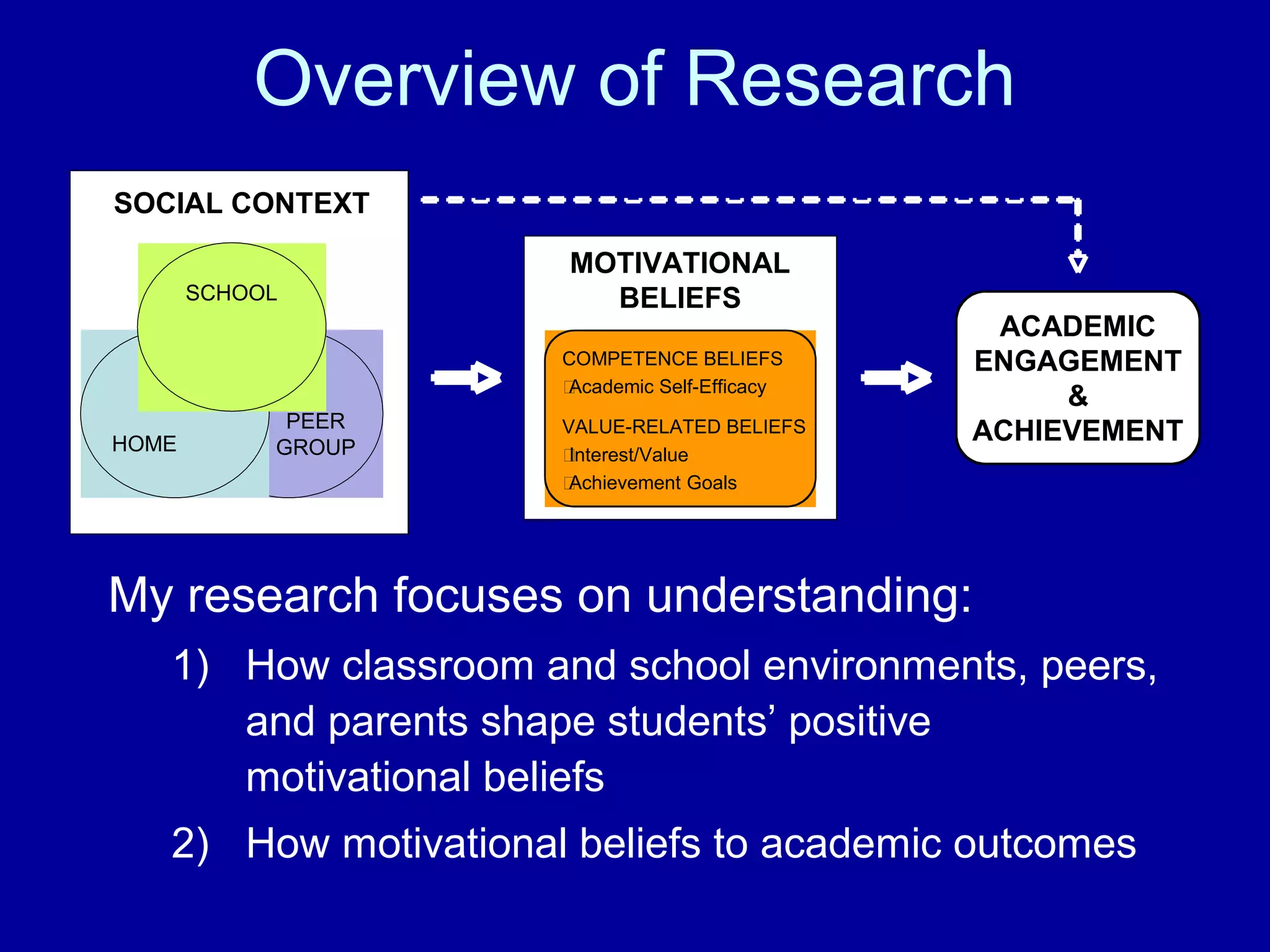

- The document summarizes research on supporting students' motivation in school, with a focus on classroom support for interest in math and science.

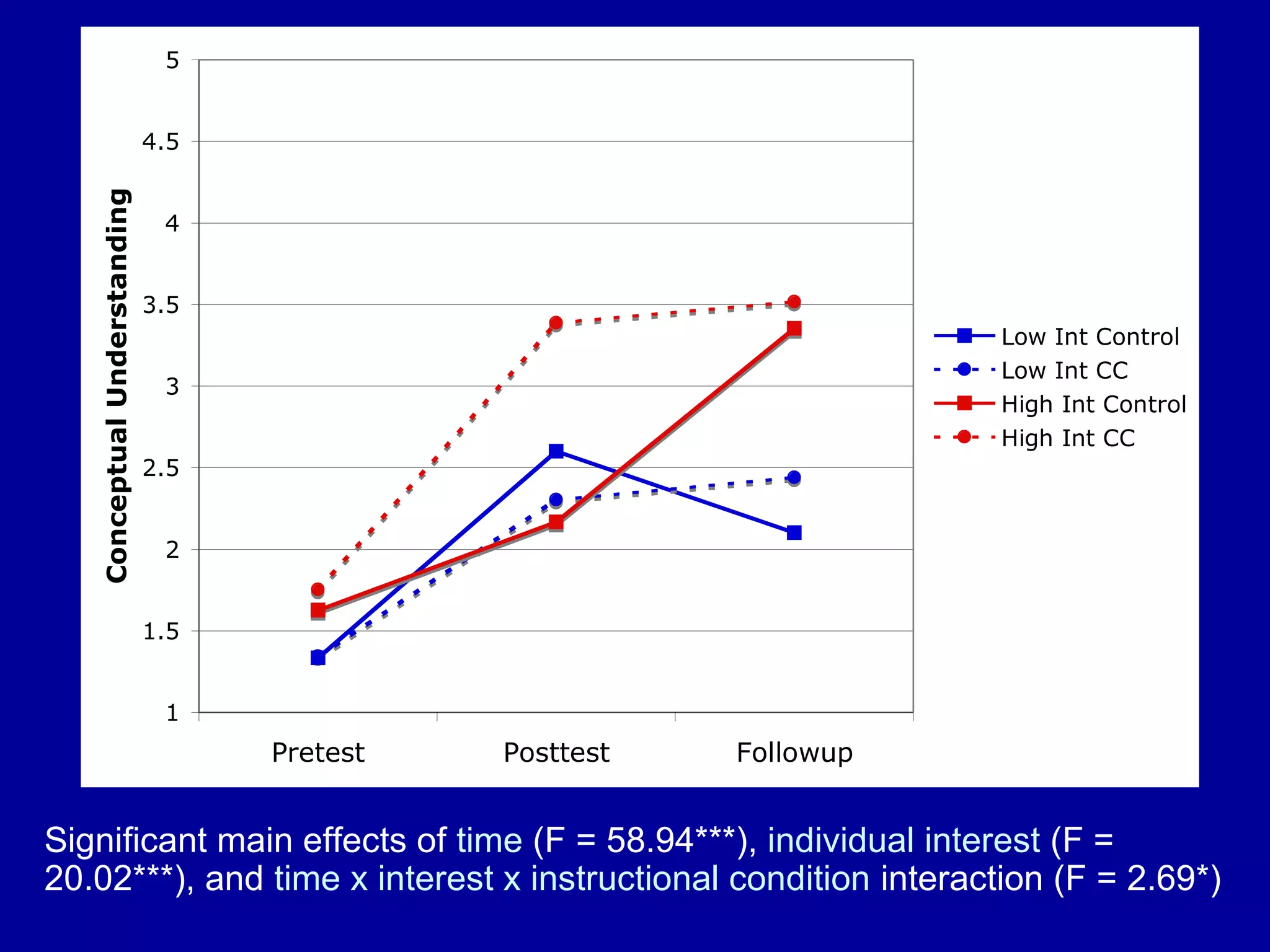

- Study 1 found that an instructional intervention to facilitate conceptual change in biology was only effective for students with high individual interest in biology.

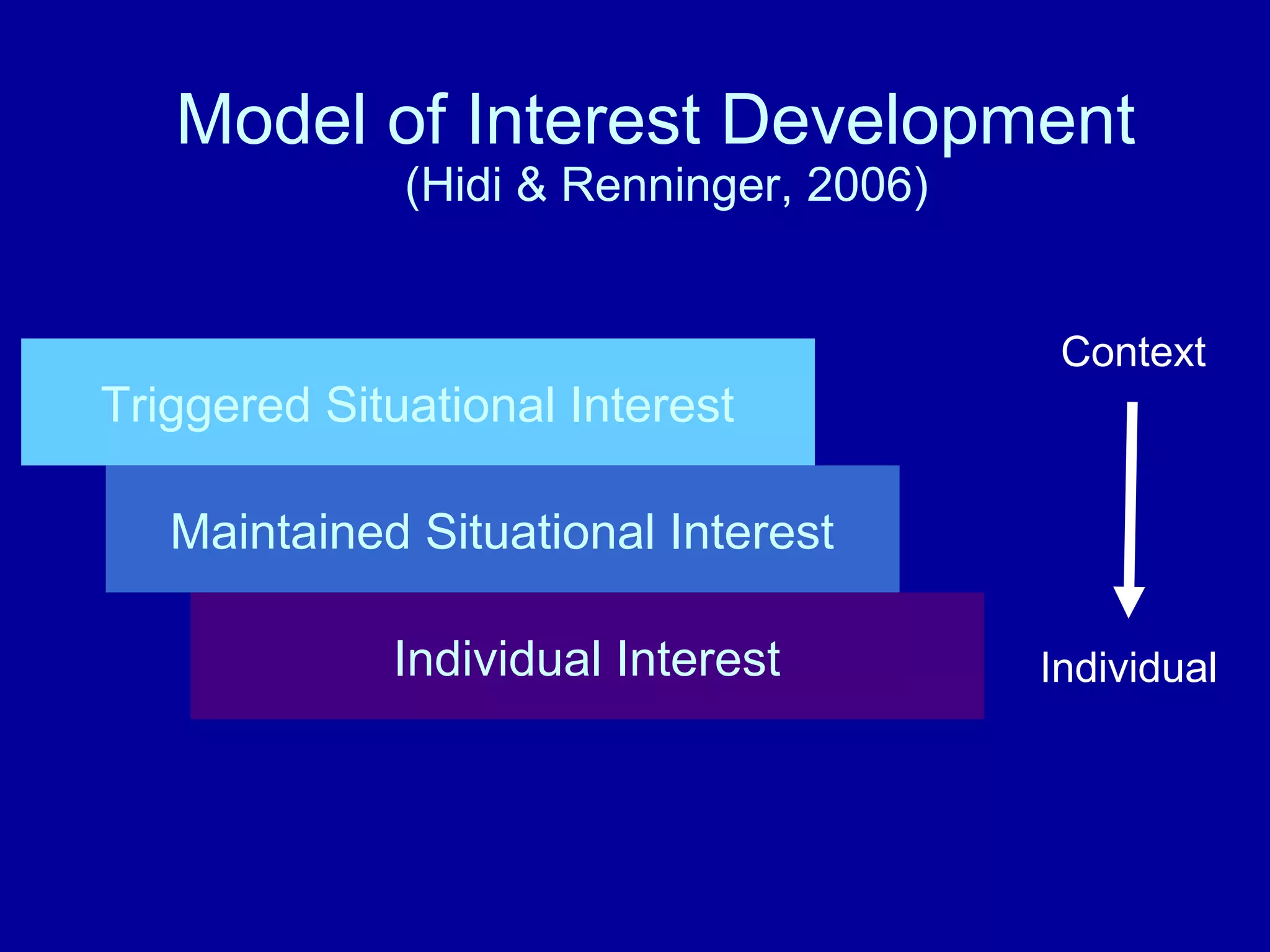

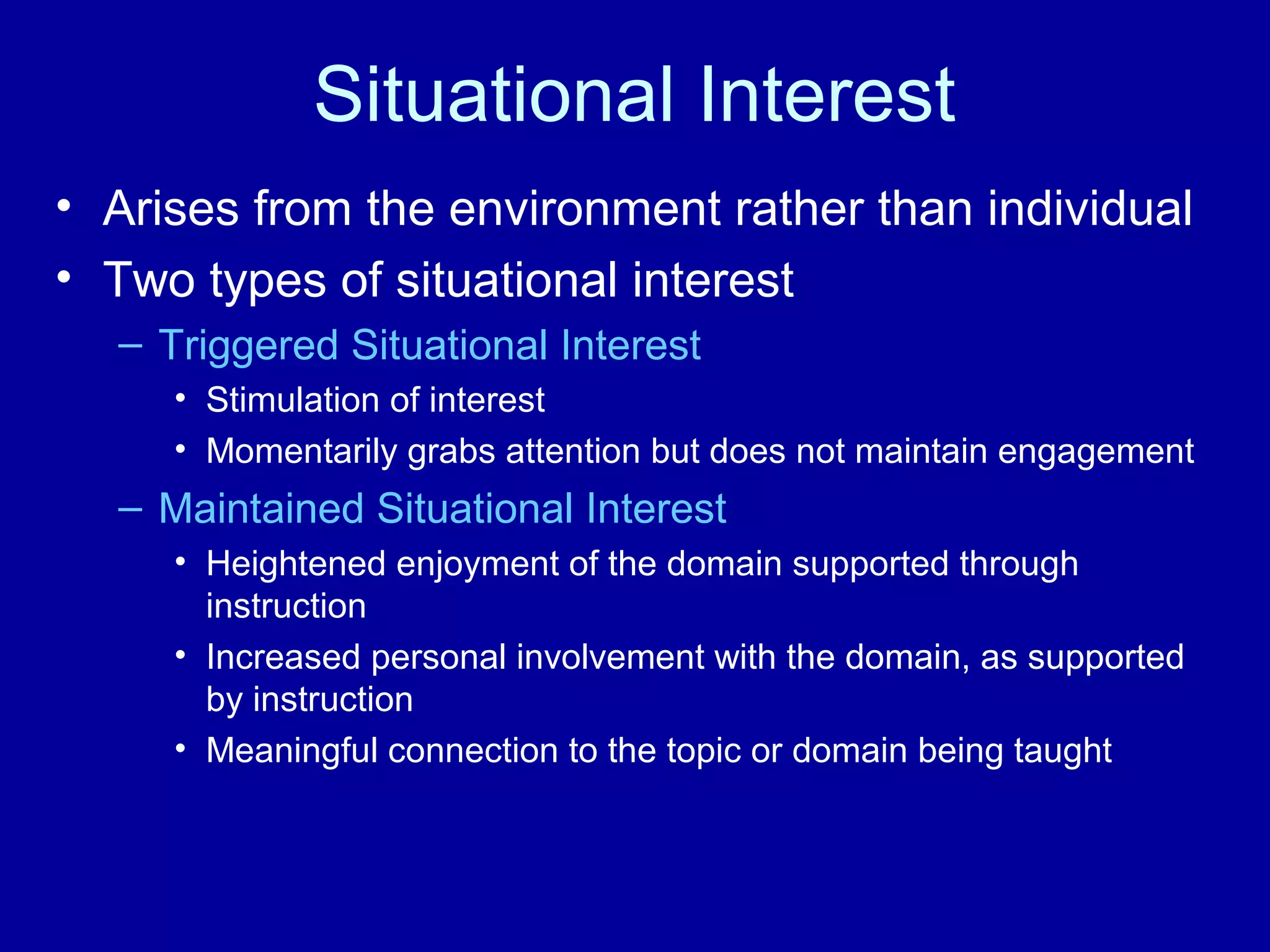

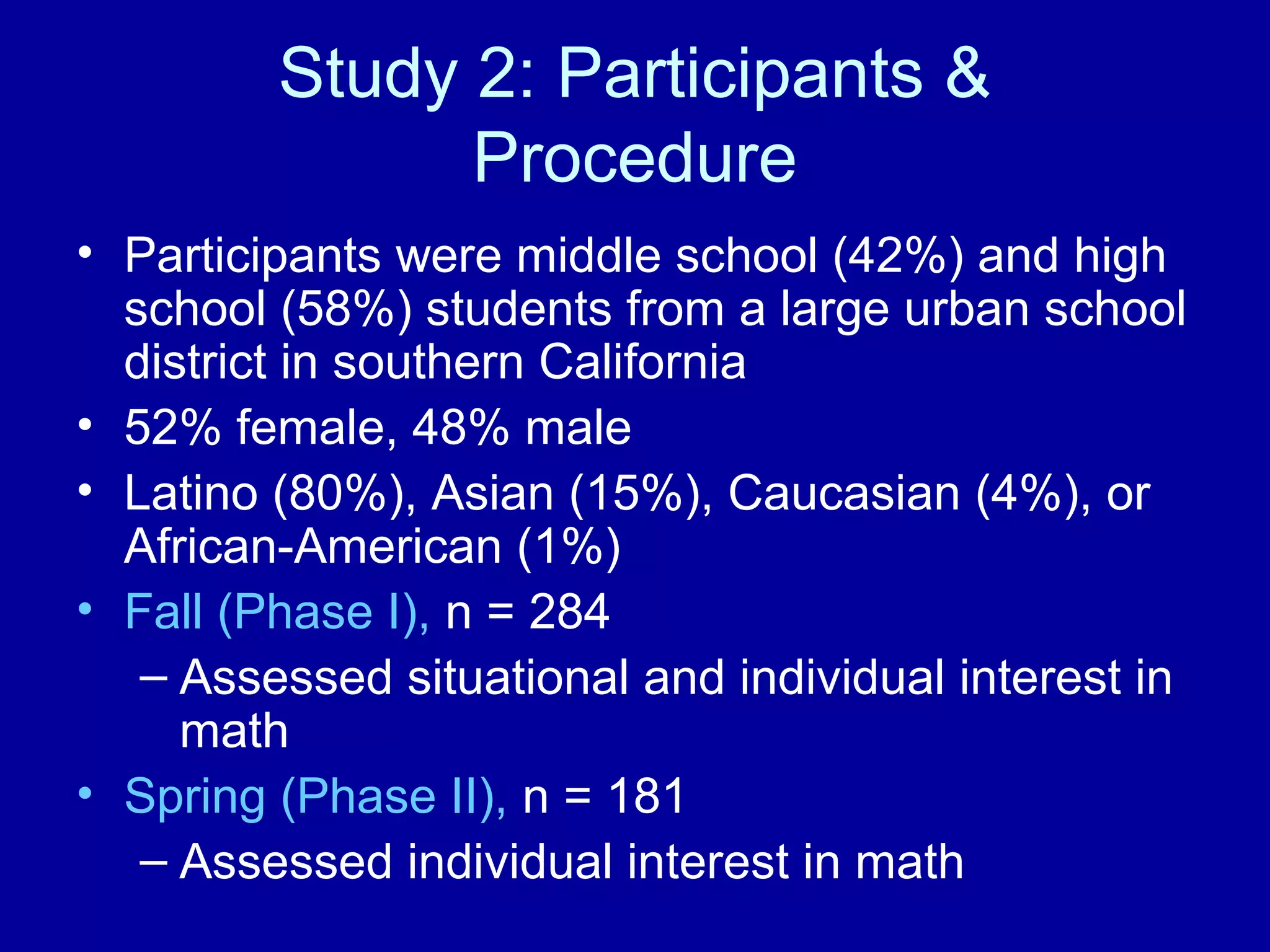

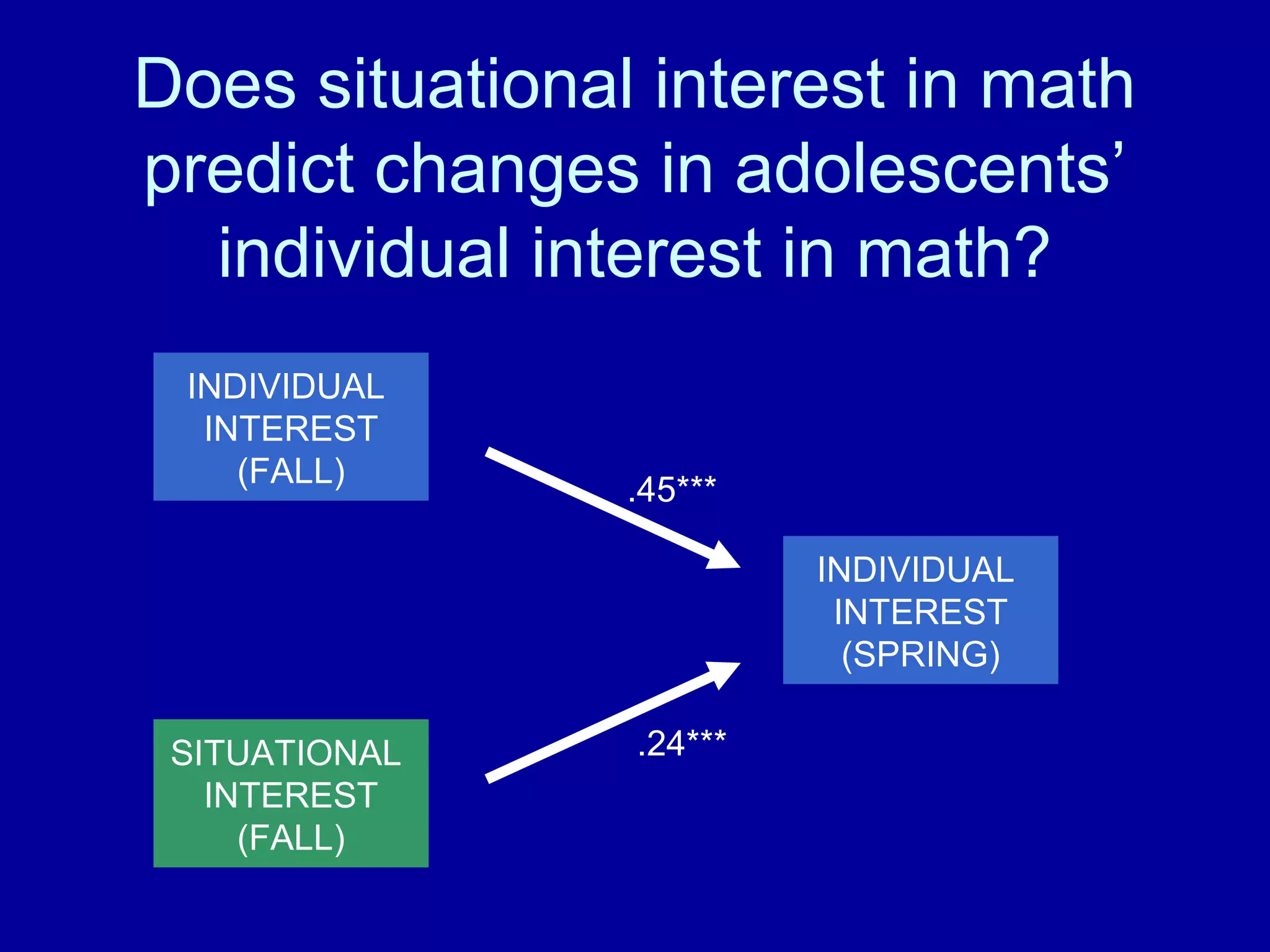

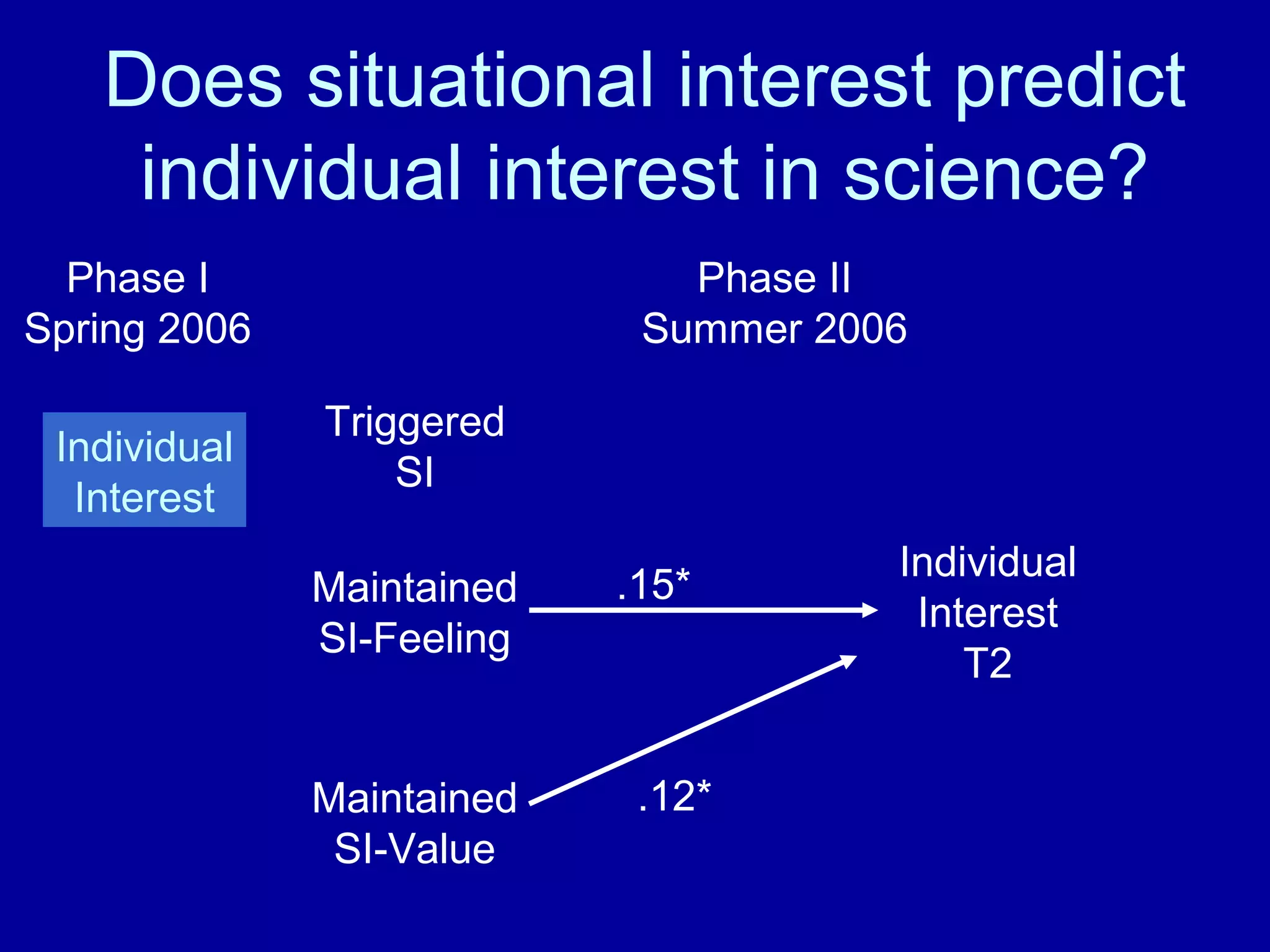

- Study 2 found that situational interest in math predicted increases in individual interest in math over time.

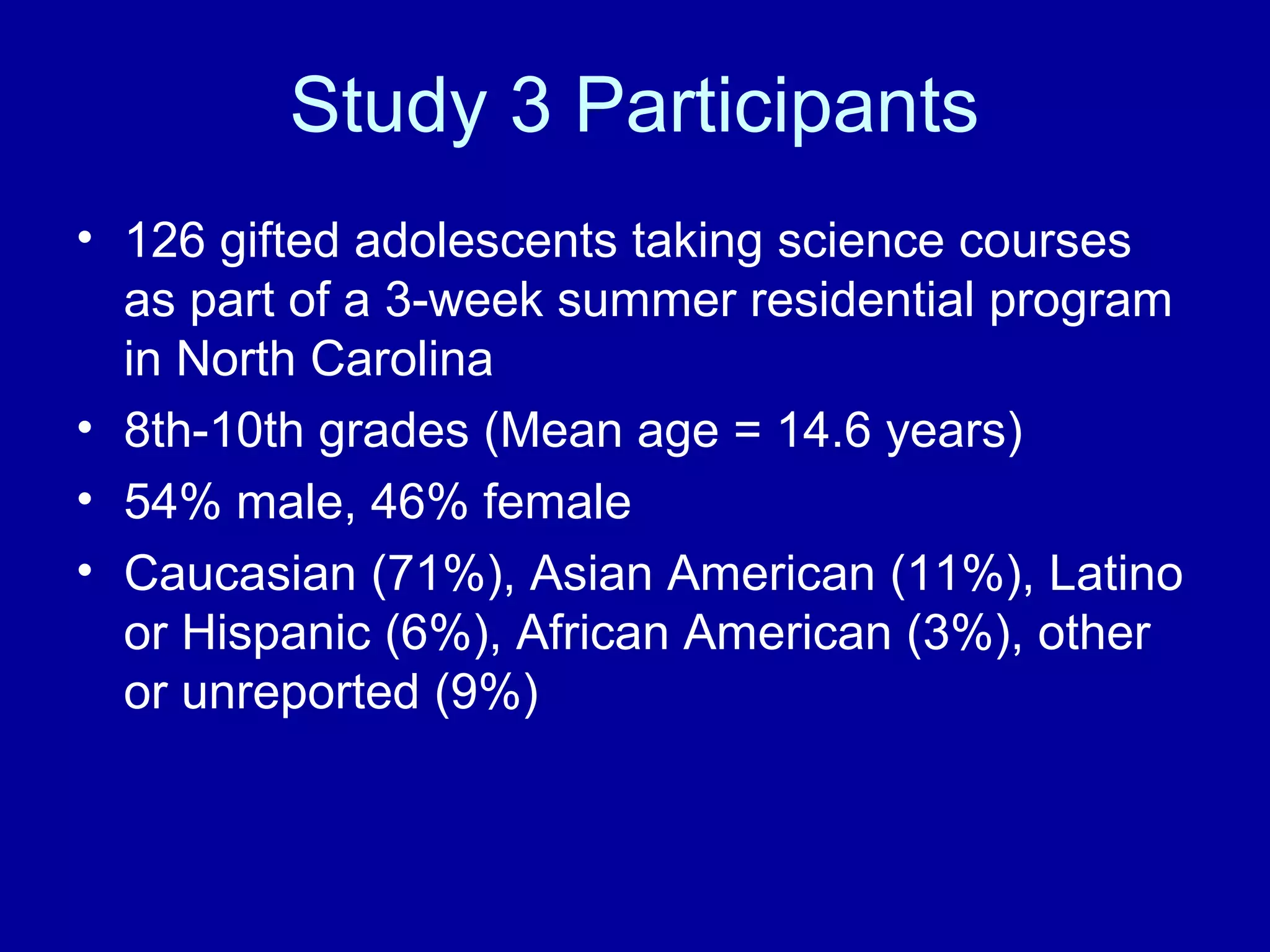

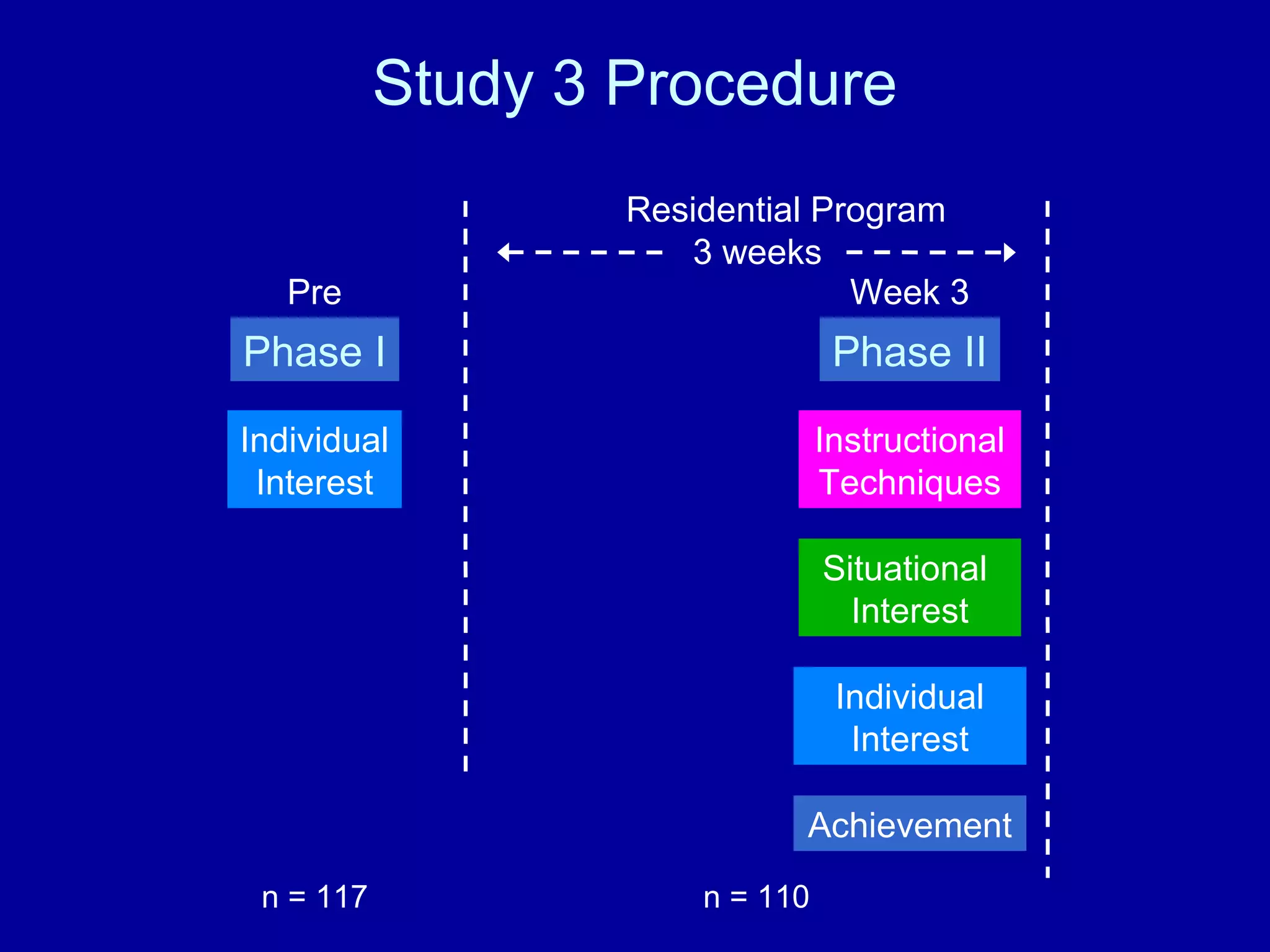

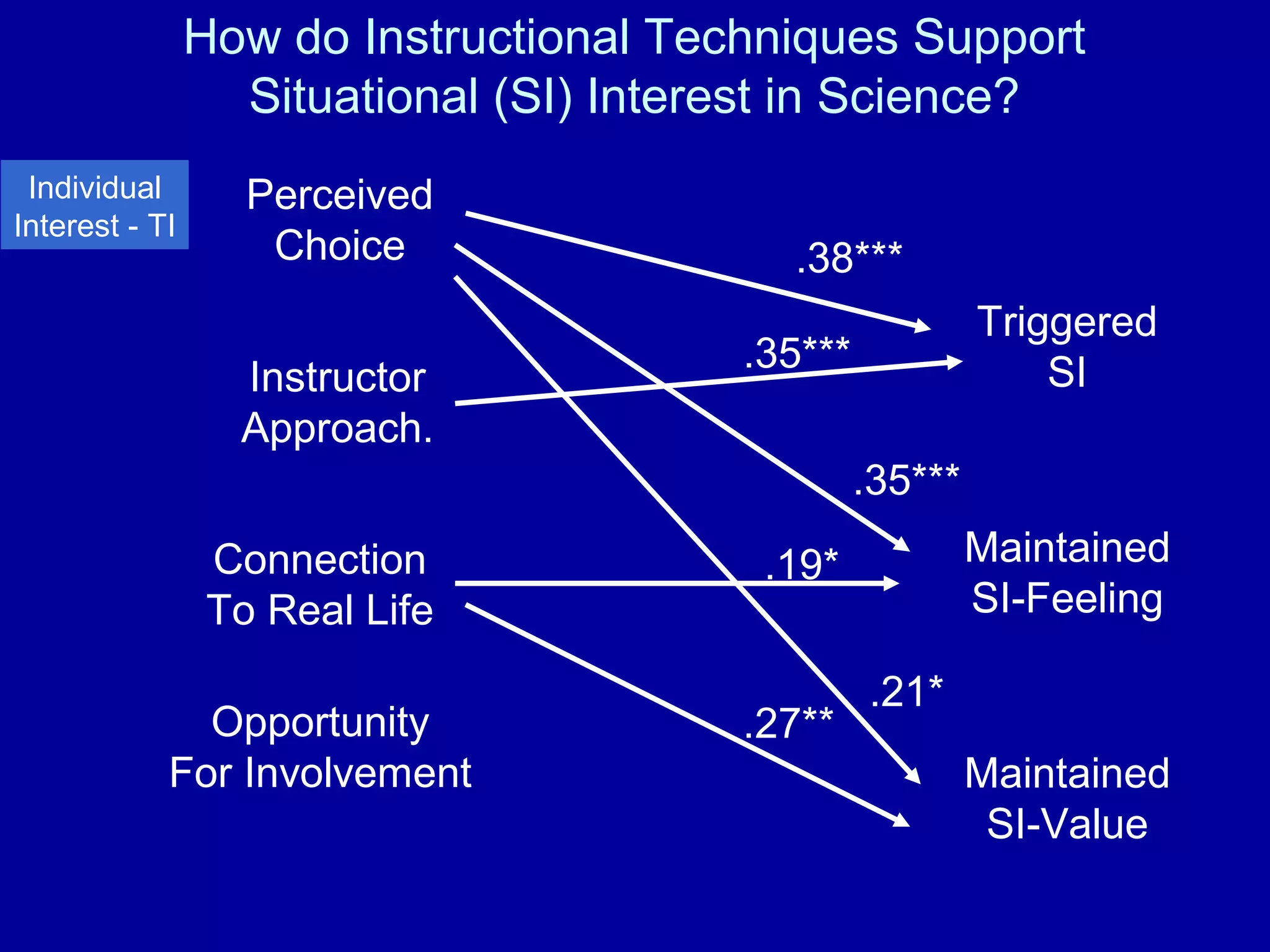

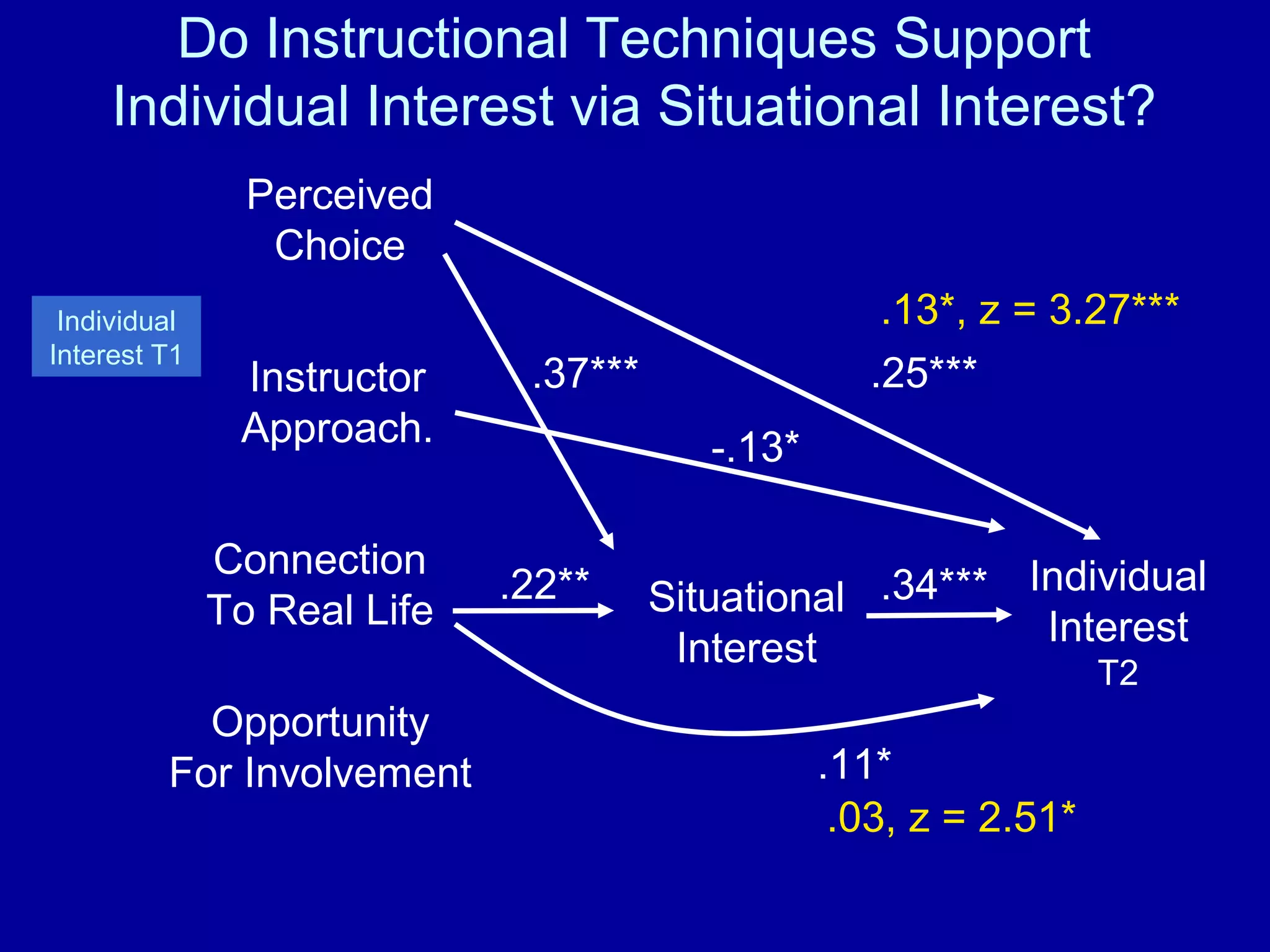

- Study 3 found that instructional techniques like providing choice, real-world connections, and opportunities for involvement supported situational interest in science, which predicted individual interest.