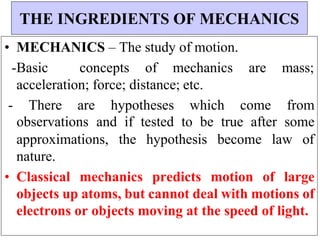

This document provides information about the Classical Mechanics course SPHA021 including:

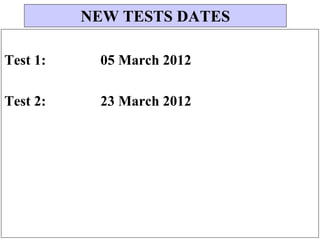

- The minimum pass mark is 50% and exam weighting is 40% while tests, practicals and assignments make up the remaining 60%.

- Attendance is important for understanding the material.

- A study guide is available for all chapters at the bookshop.

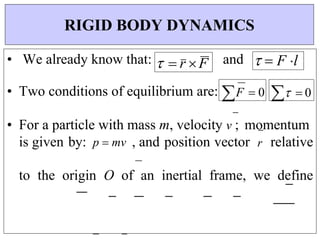

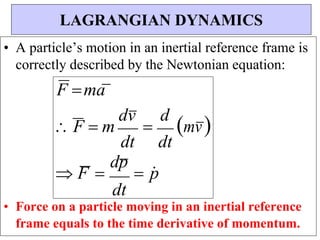

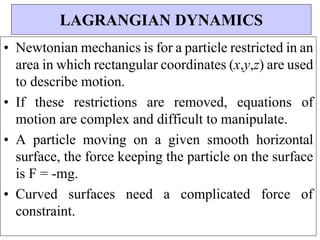

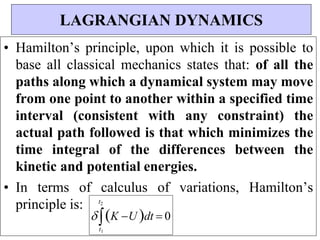

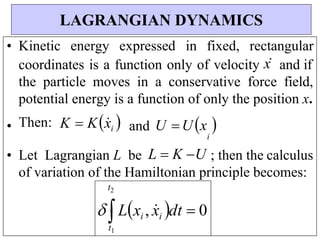

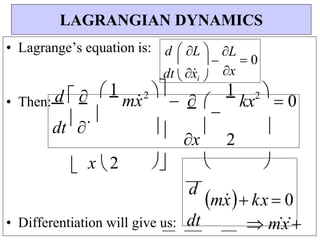

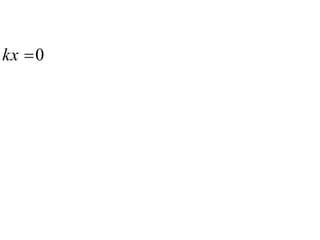

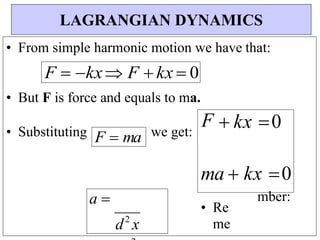

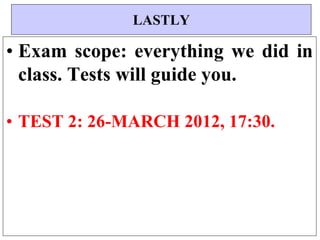

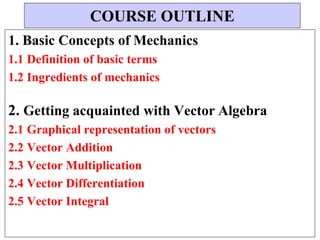

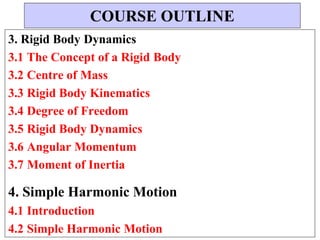

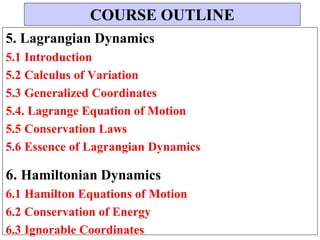

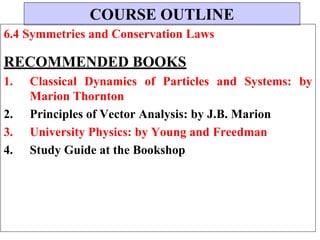

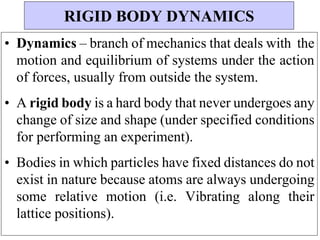

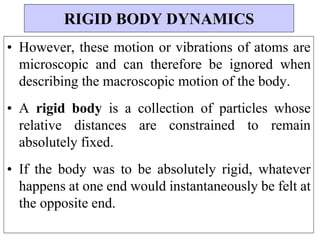

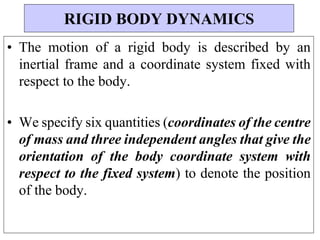

- The course outline covers topics like rigid body dynamics, simple harmonic motion, Lagrangian and Hamiltonian dynamics. Recommended textbooks are also listed. There will be two assignments, two tests and quizzes throughout the semester.

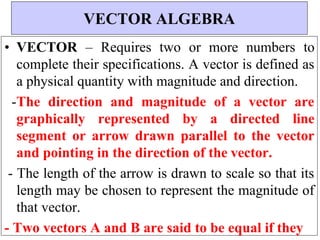

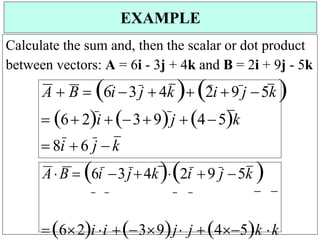

![1. Consider two vectors: A 3i 2 j and B i 4 j .

(i) Calculate: A B

(ii) The direction of: A B

2. Find the angle between the vectors: A 4i 2 j 5k and

B 2i 10 j 7k.

3. Show that: AB C ABAC

given that vectors

A 7i 4 j 11k , B 6i 9 j 8k and C 3i 3j 4k . Also show

QUIZ No.1 [VECTOR C INCLUDED]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/spha021notes-classicalmechanics-2020-221110014135-156858a6/85/SPHA021-Notes-Classical-Mechanics-2020-docx-60-320.jpg)

![• A water (H2O) molecule consists of two hydrogen

atoms and one oxygen atom. The oxygen atom is

located at the origin. One hydrogen atom is between

the positive x-axis and positive y-axis and the other

hydrogen atom is between the positive x-axis and the

negative y-axis. Each hydrogen atom makes an angle

of 60º with the positive x-axis and they are both a

distance d = 9.57 nm from the origin. Draw a rough

sketch of the water molecule and then calculate the

center of mass of the water molecule. The mass of

oxygen is 16.0 g and of hydrogen is 1.0

g. [Note: 1 nm = 10-9 m]

EXAMPLE [DO IT YOURSELF]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/spha021notes-classicalmechanics-2020-221110014135-156858a6/85/SPHA021-Notes-Classical-Mechanics-2020-docx-89-320.jpg)