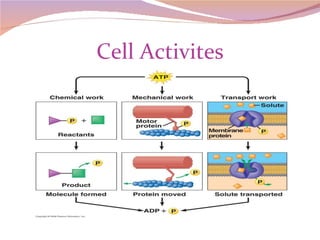

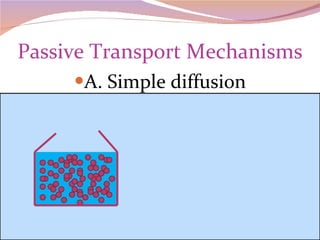

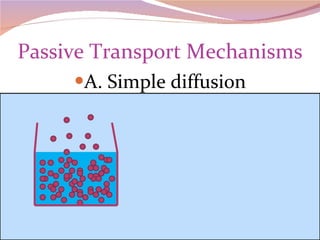

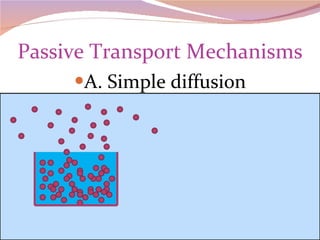

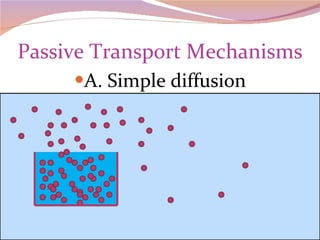

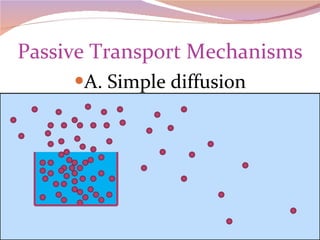

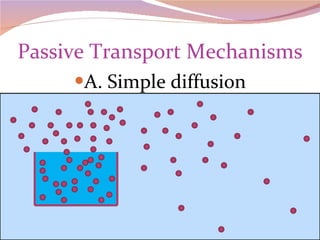

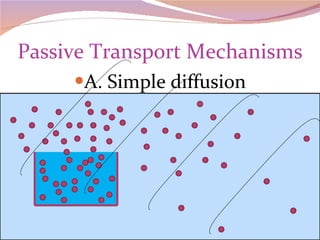

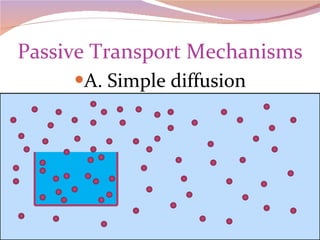

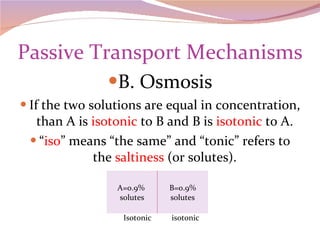

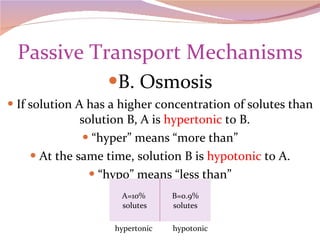

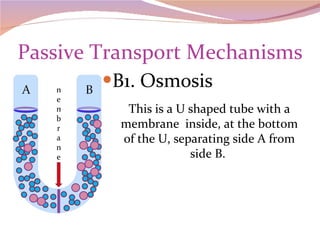

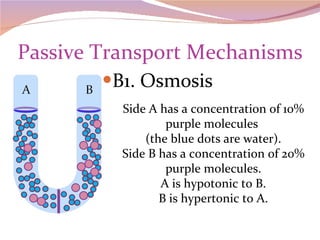

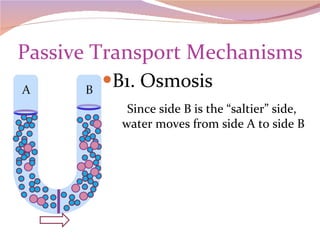

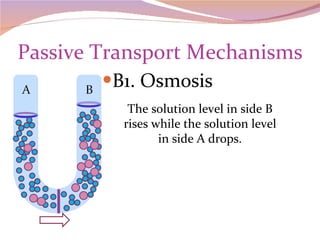

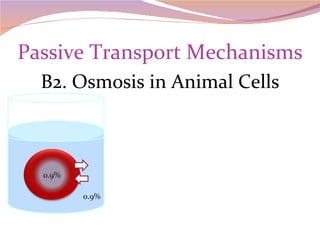

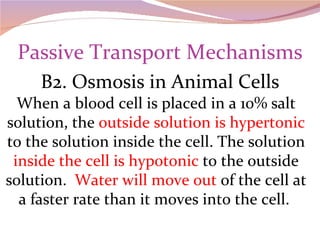

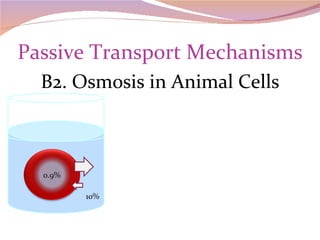

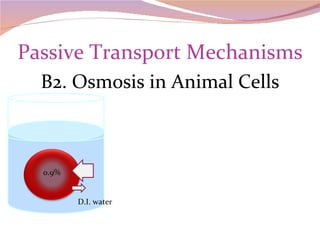

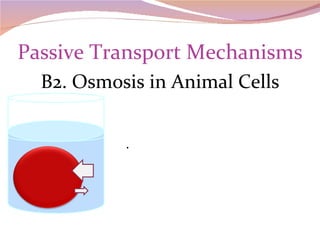

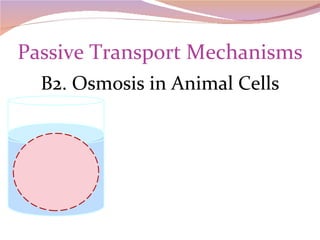

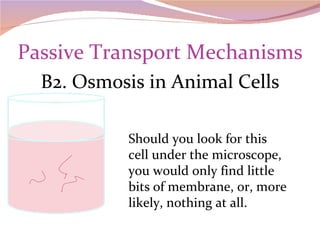

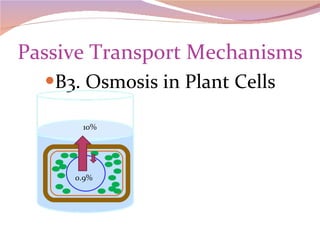

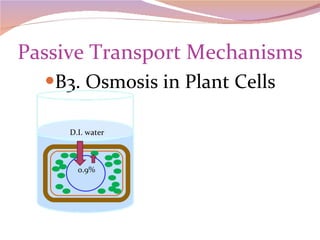

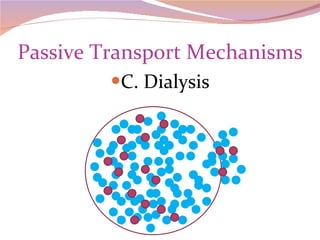

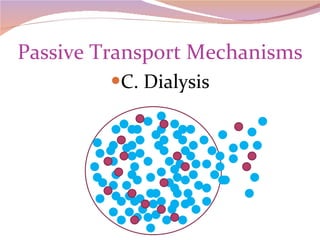

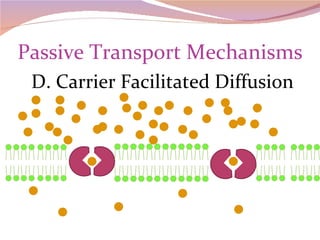

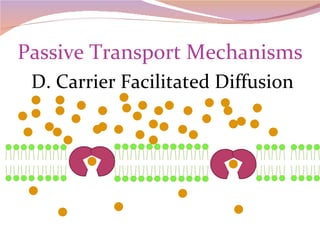

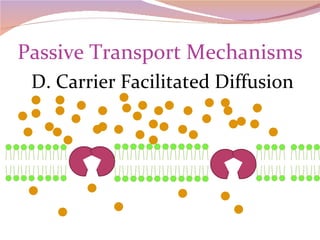

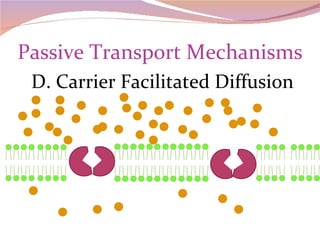

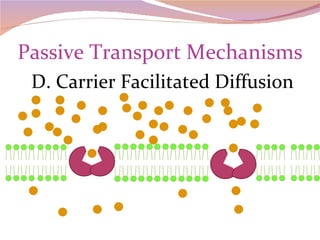

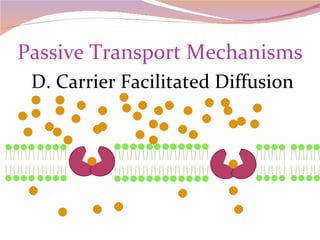

Cells have three basic types of activities: transport, chemical, and mechanical. Transport activities include passive transport mechanisms like simple diffusion, osmosis, dialysis, and carrier-facilitated diffusion. Passive transport relies on concentration gradients and molecular motion, and does not require energy input from the cell. Osmosis is the diffusion of water across a membrane according to solute concentration gradients, which can cause animal cells to shrink or burst and plant cells to plasmolyze or become turgid.