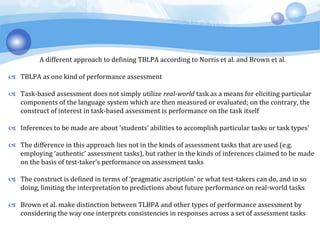

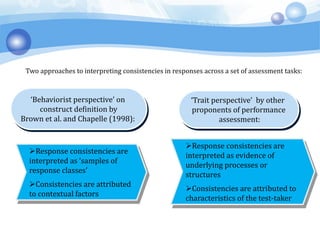

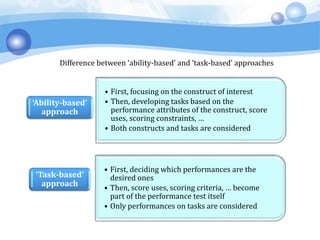

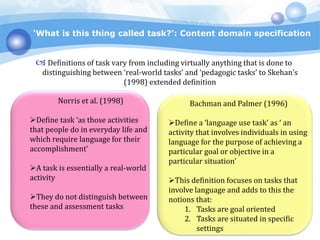

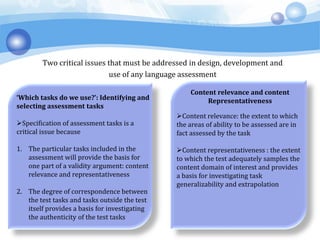

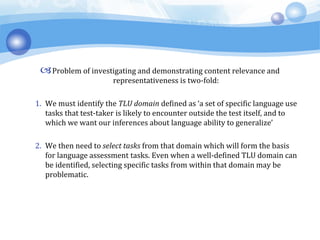

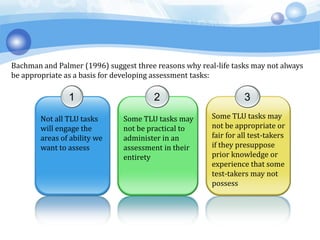

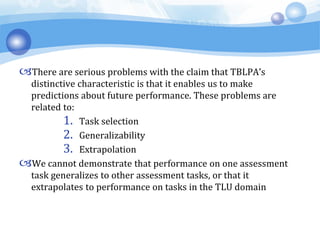

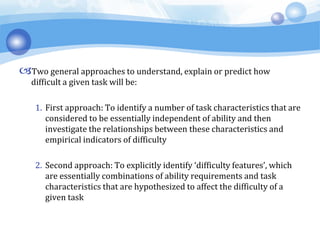

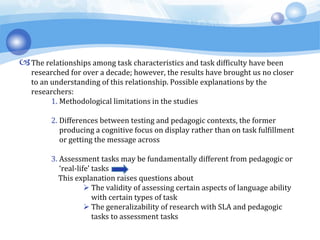

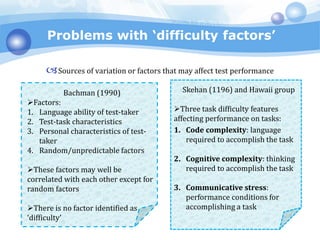

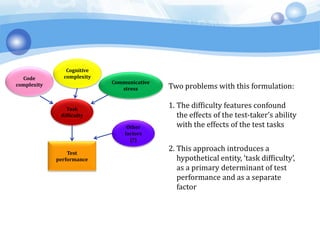

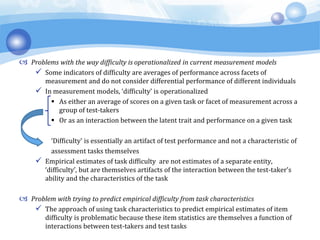

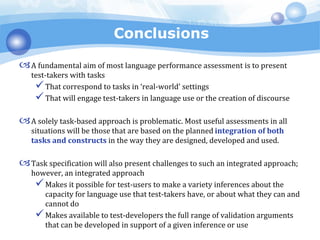

This document summarizes some key issues in task-based language performance assessment (TBLPA). It discusses how TBLPA relates to direct testing approaches from the 1970s and how tasks are defined. Two critical issues are identifying relevant tasks to assess the target language use domain and determining task difficulty, which does not reside in the task alone but depends on the test-taker. Problems are discussed around claims that TBLPA enables predictions of future performance, as well as understanding task difficulty based on characteristics alone. The conceptualization of difficulty in measurement models is also examined.