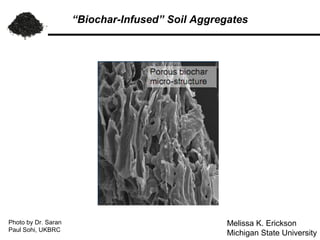

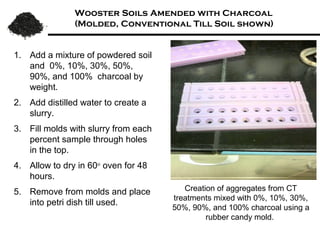

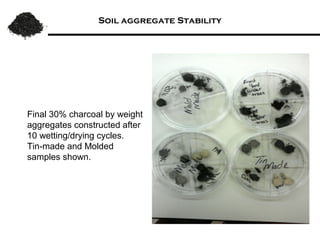

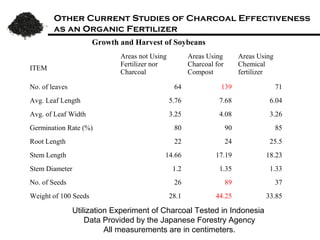

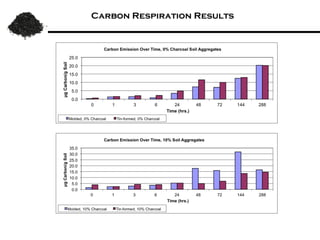

This document summarizes research on amending soils with biochar or charcoal. It finds that charcoal amendment can increase seed germination, plant growth, and crop yields. Specifically, it leads to enhanced soil structure and nutrients, increased water retention, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Studies showed increased aggregate stability and carbon sequestration in soils mixed with 10-50% charcoal. Respiration rates were similar for aggregates with up to 90% charcoal. Finer-textured conventional tilled soils allowed better charcoal penetration than other soils. Overall, the research demonstrates the agricultural and environmental benefits of charcoal-amended soils.