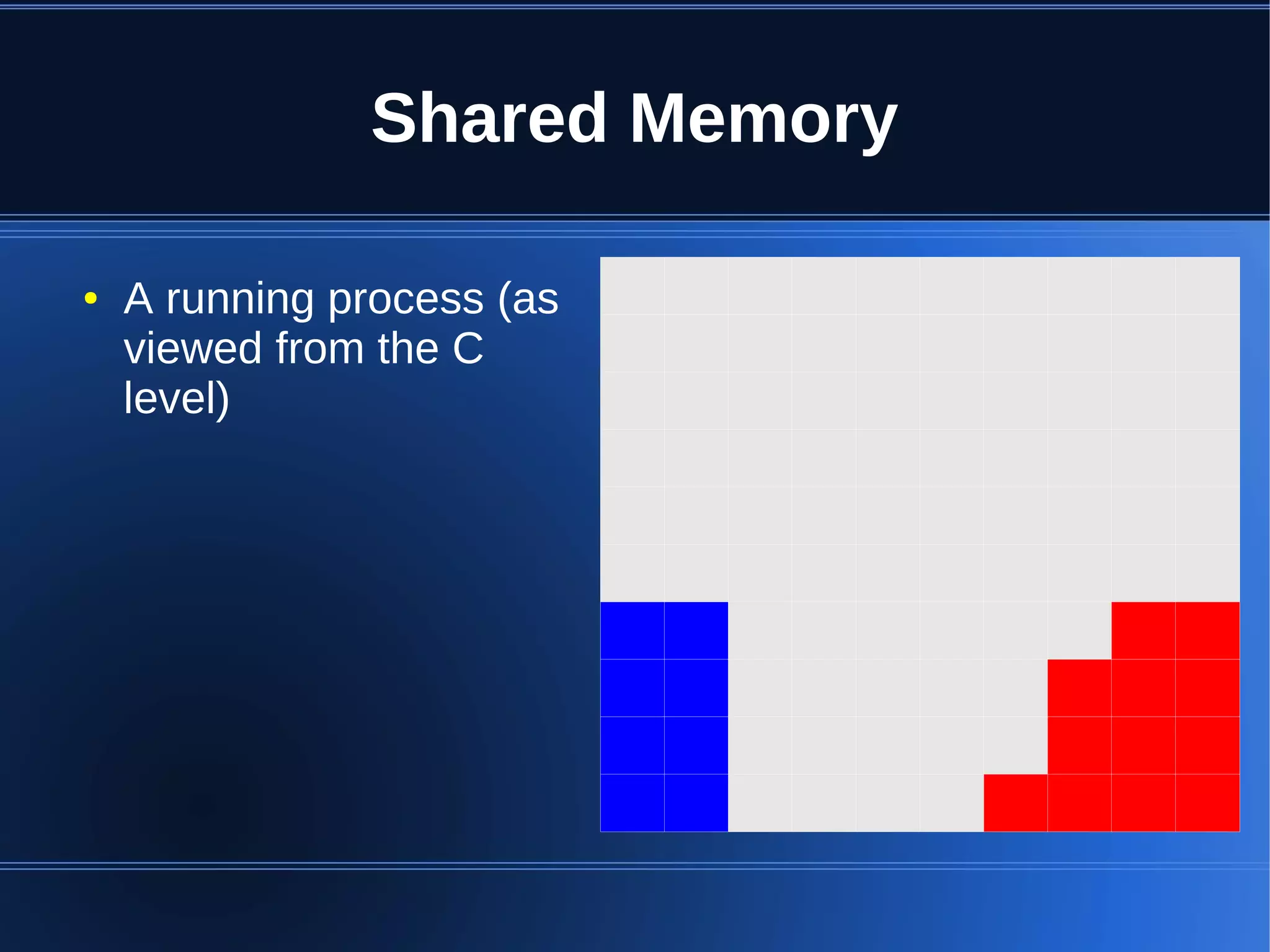

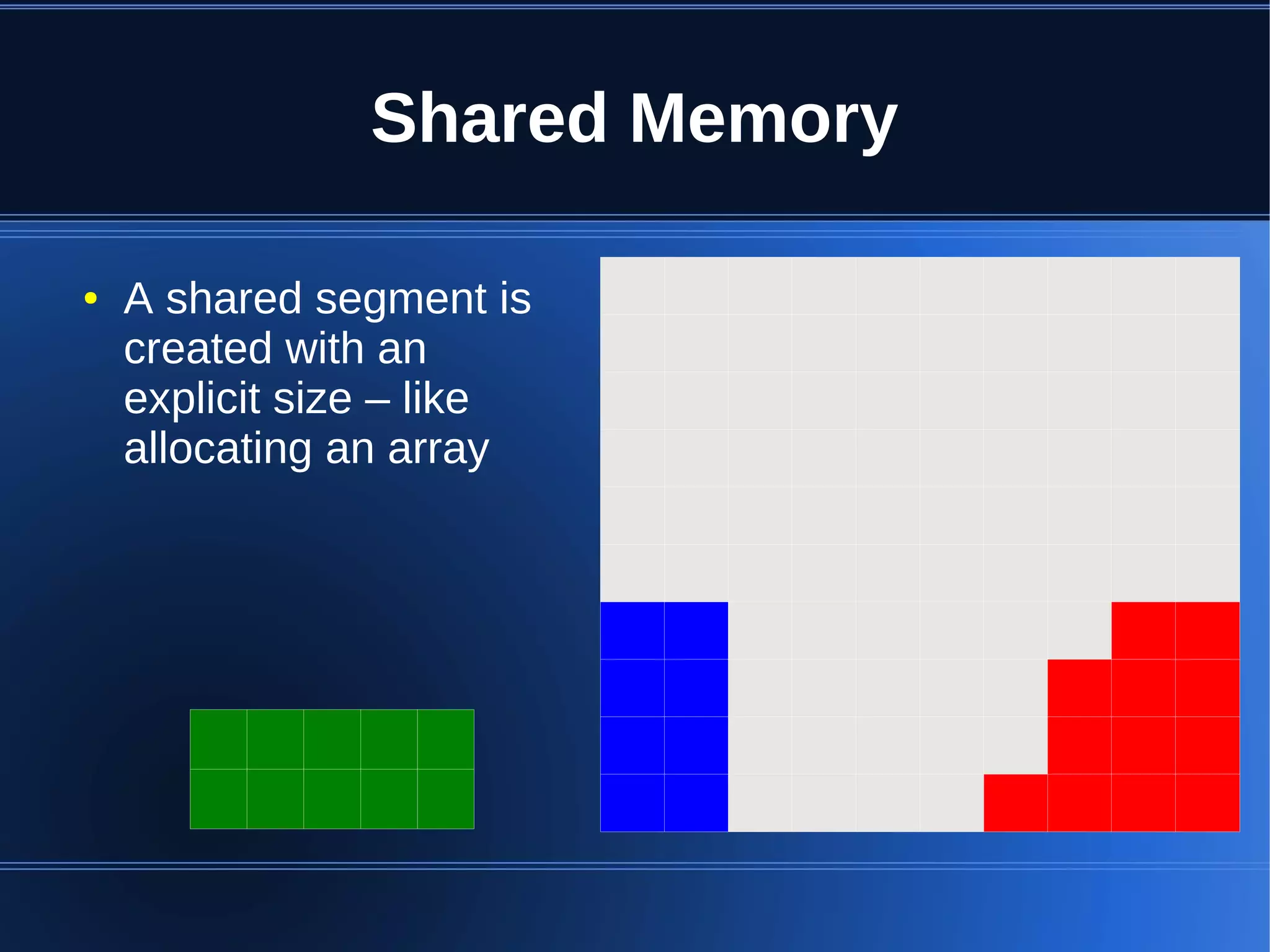

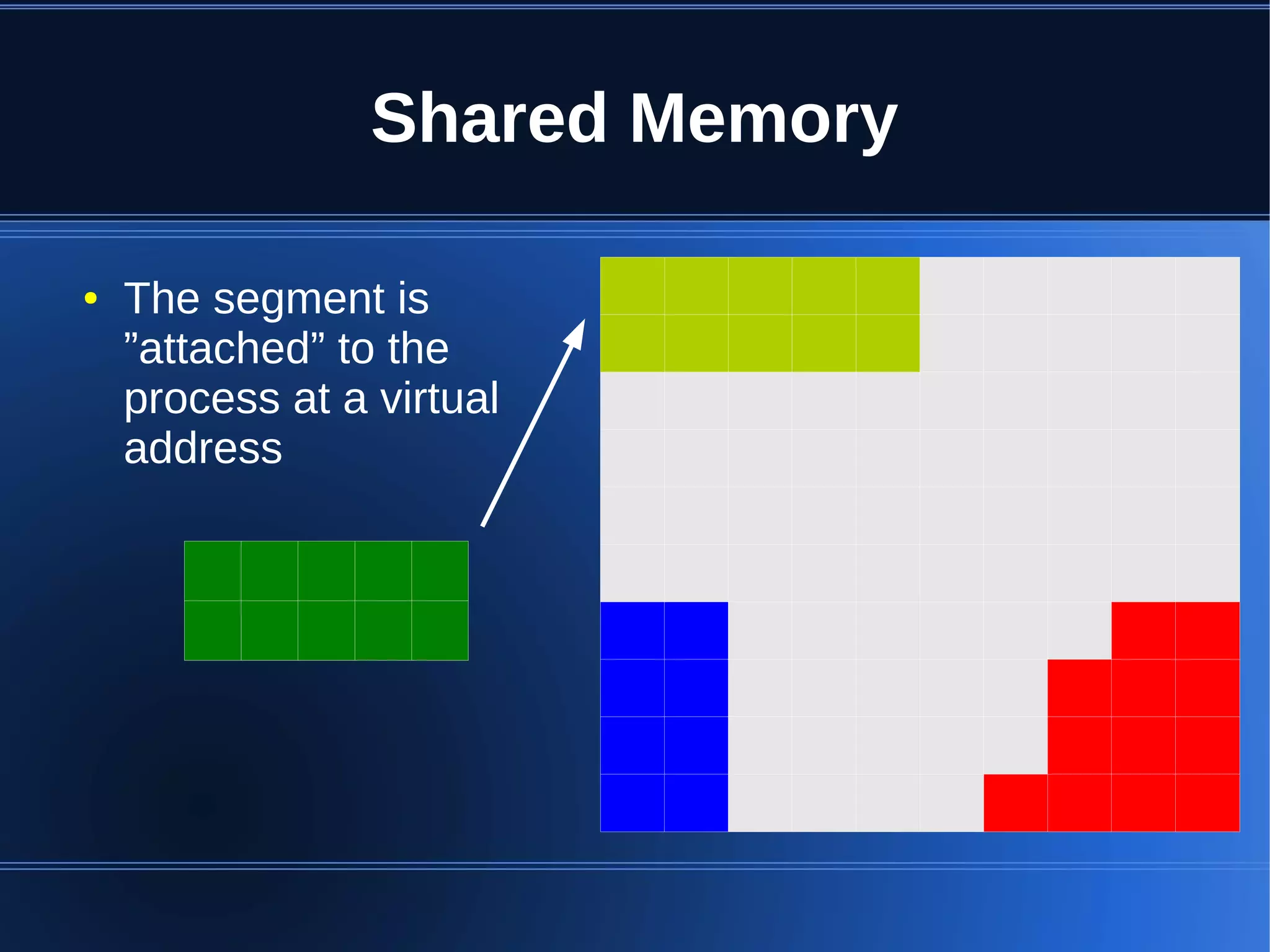

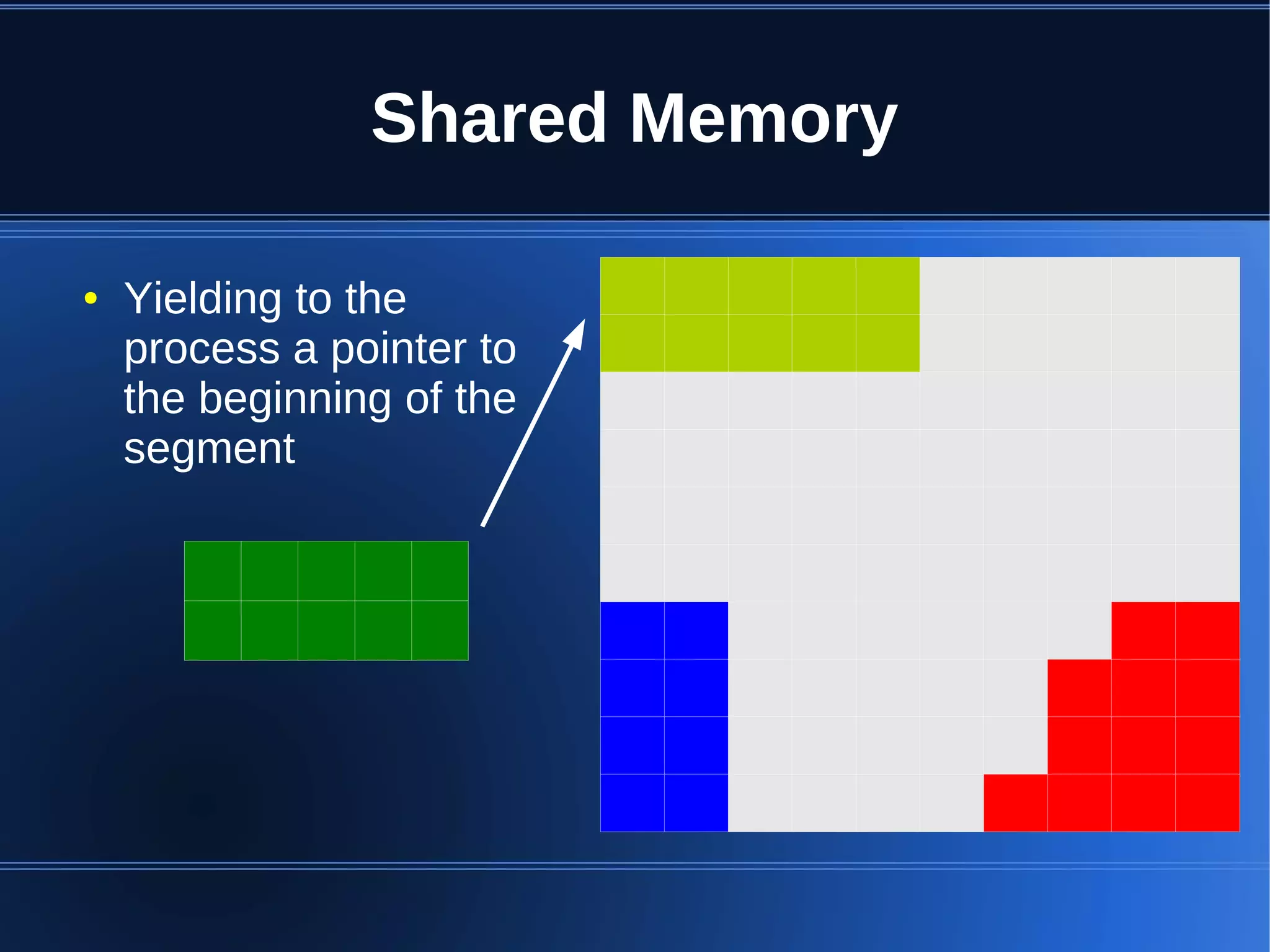

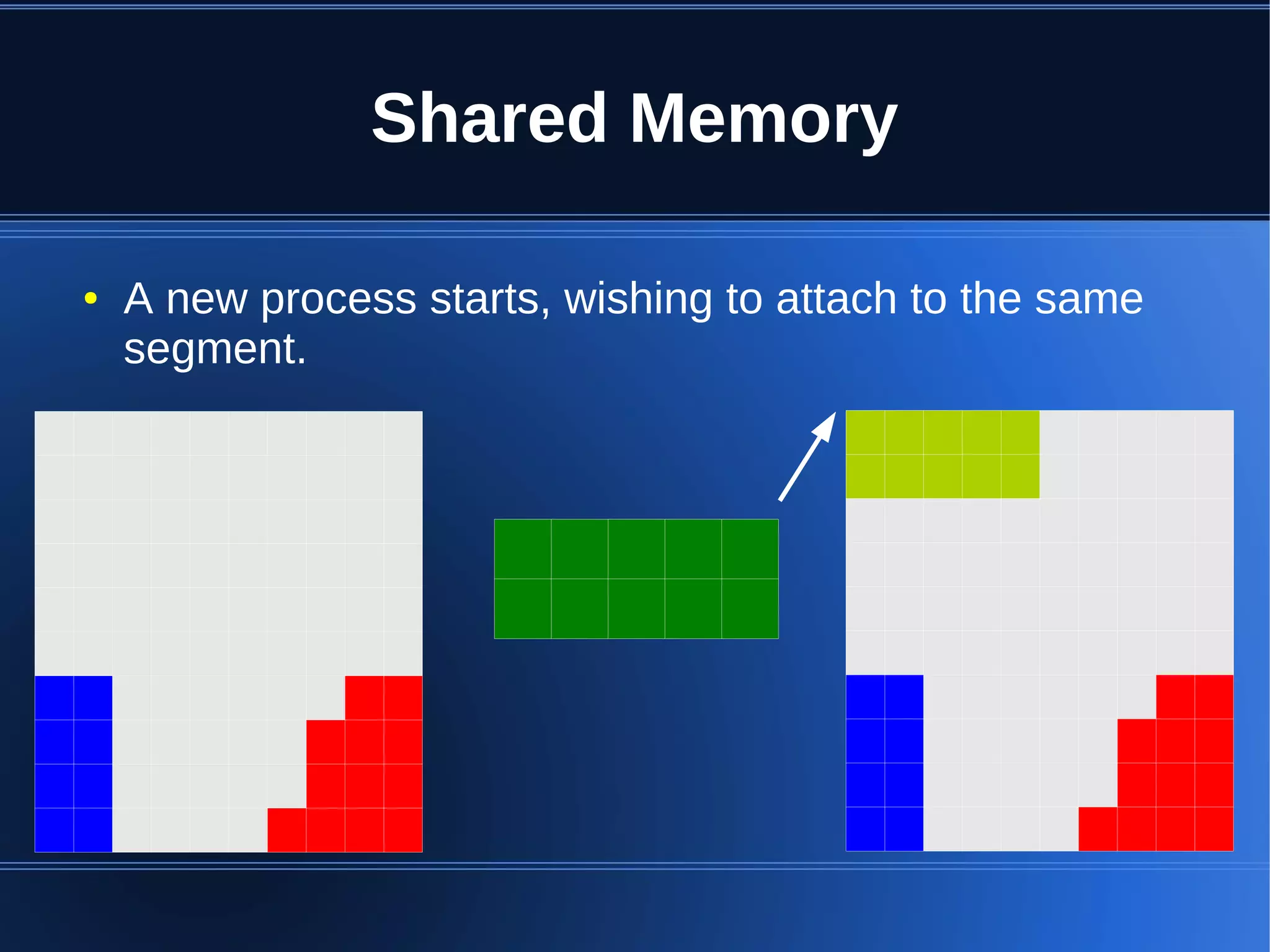

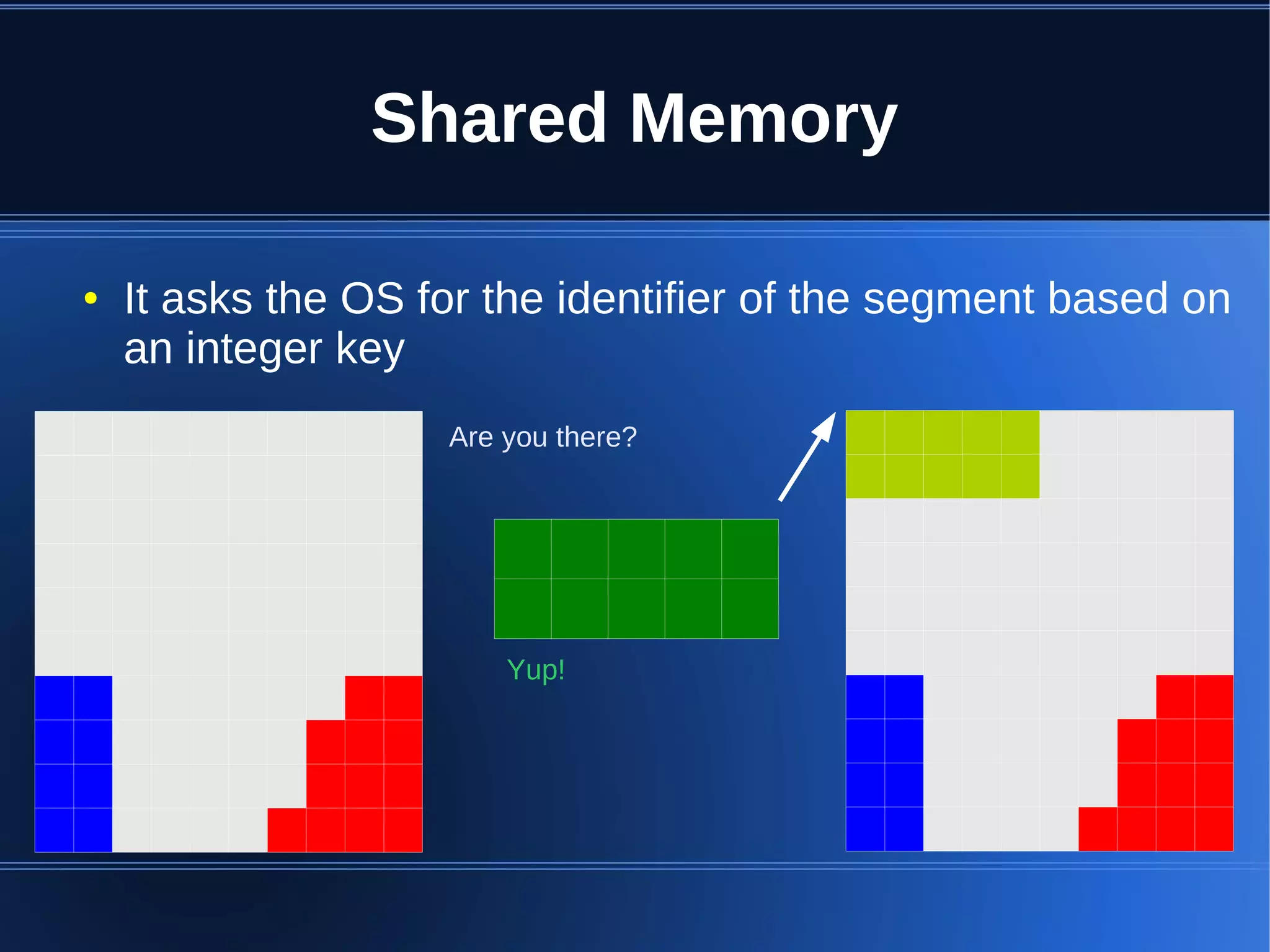

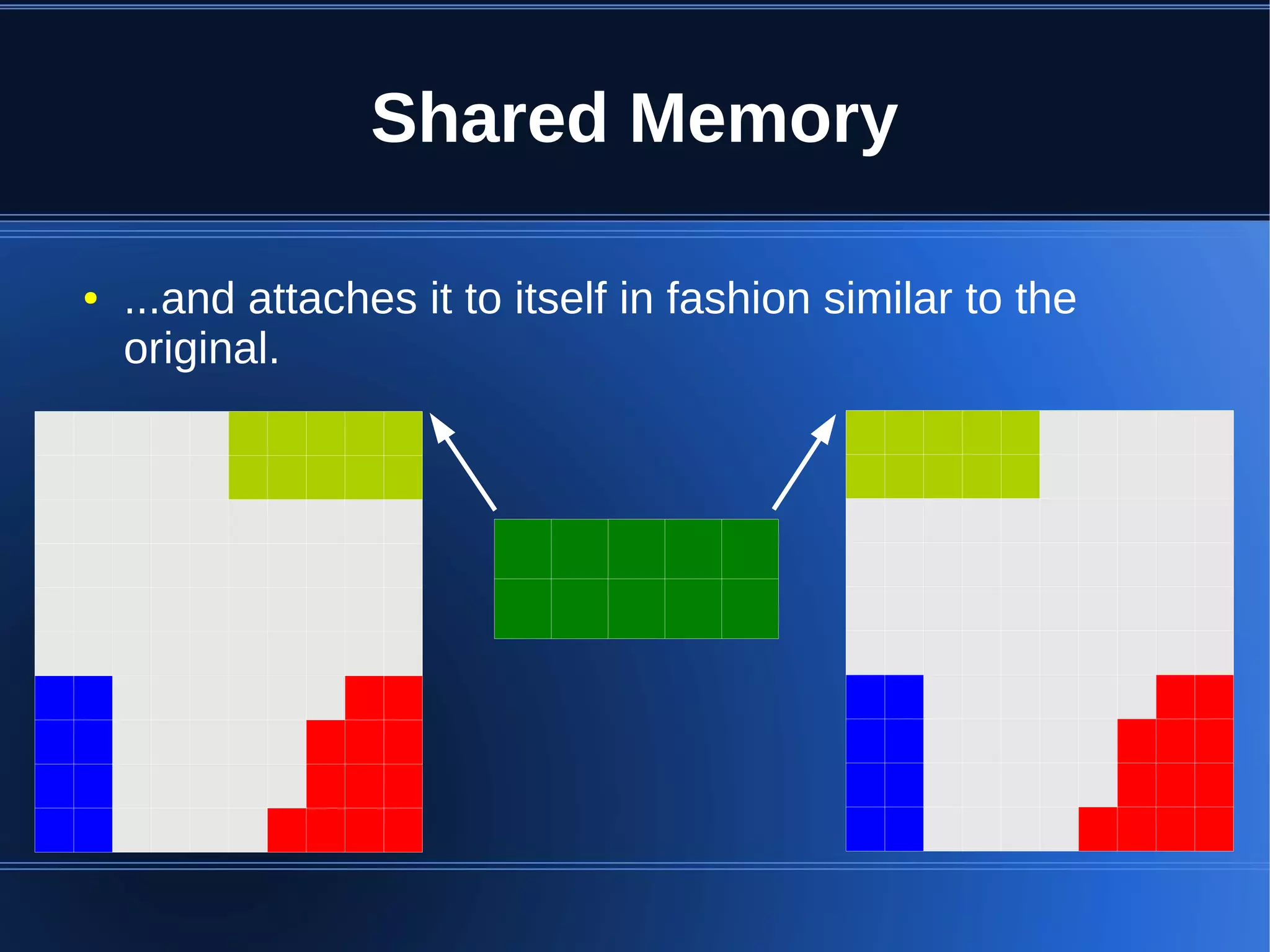

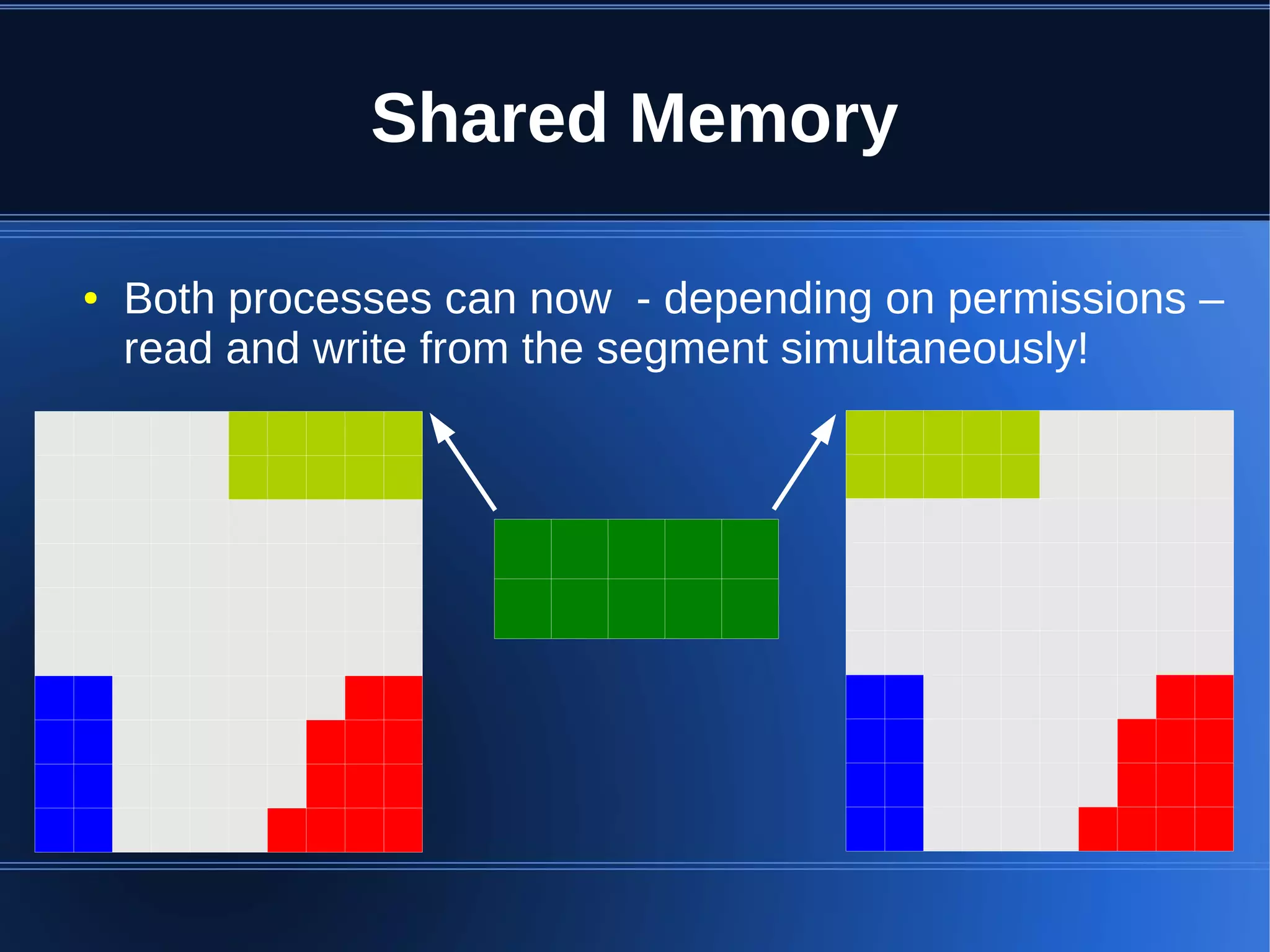

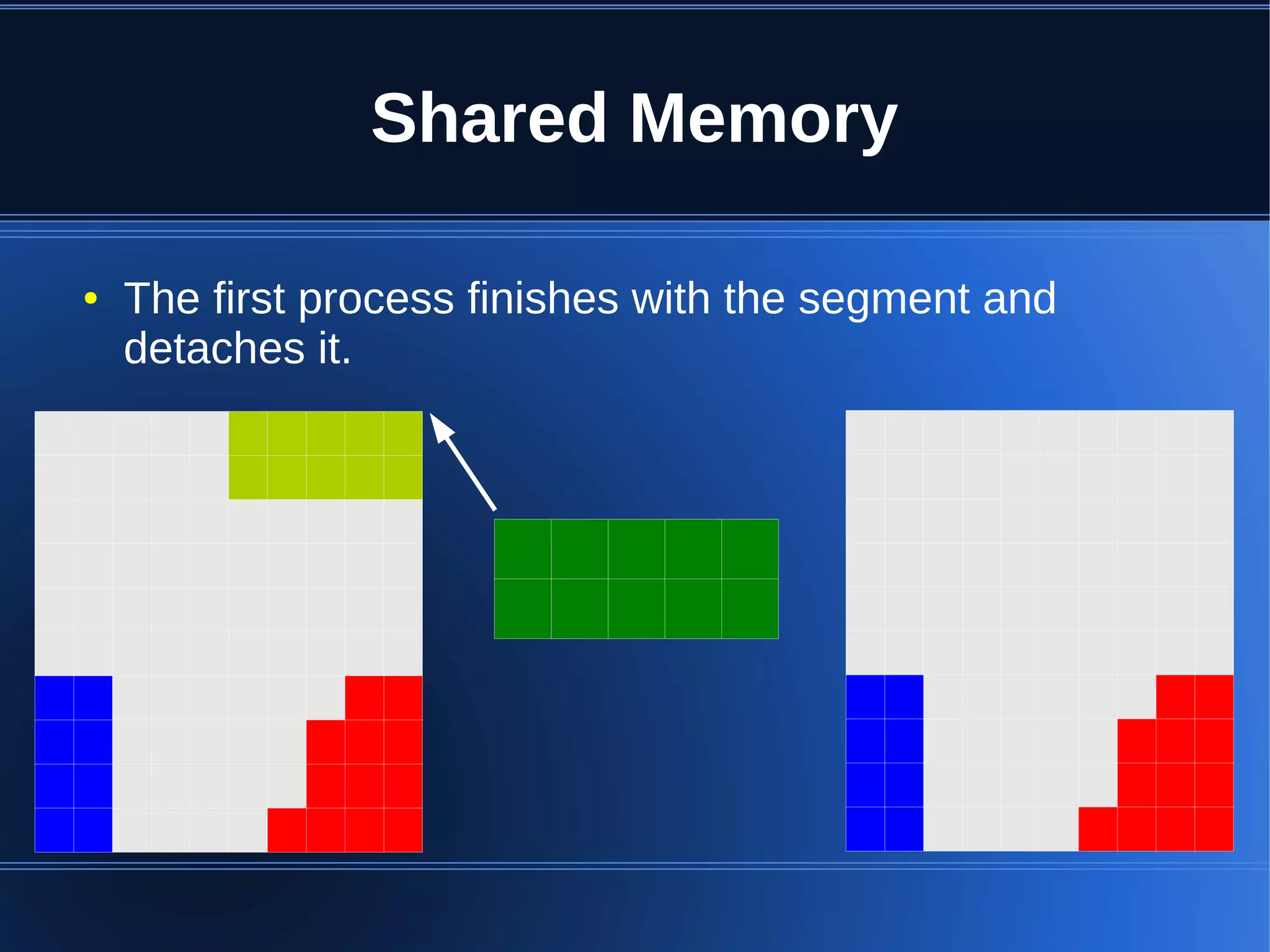

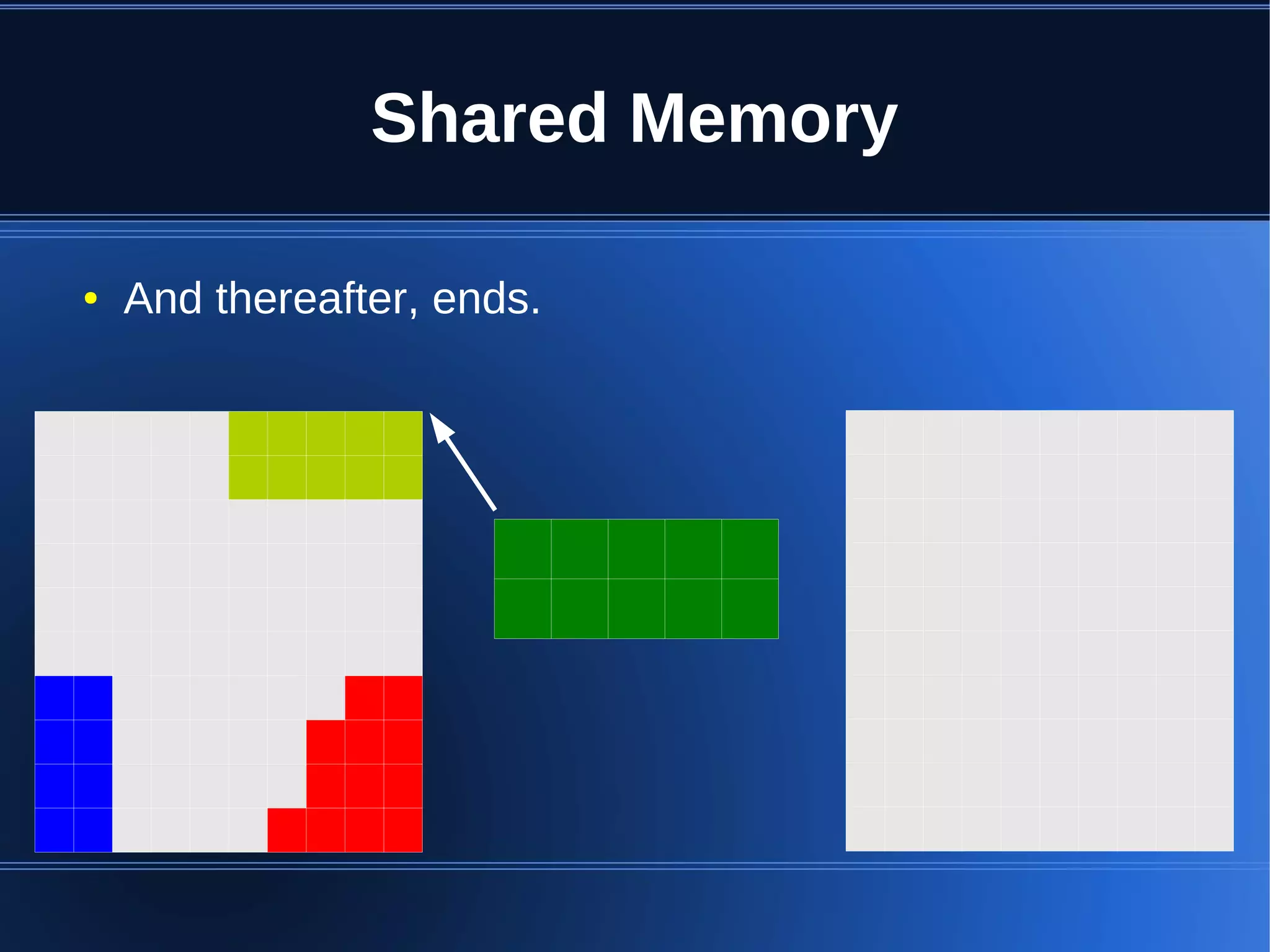

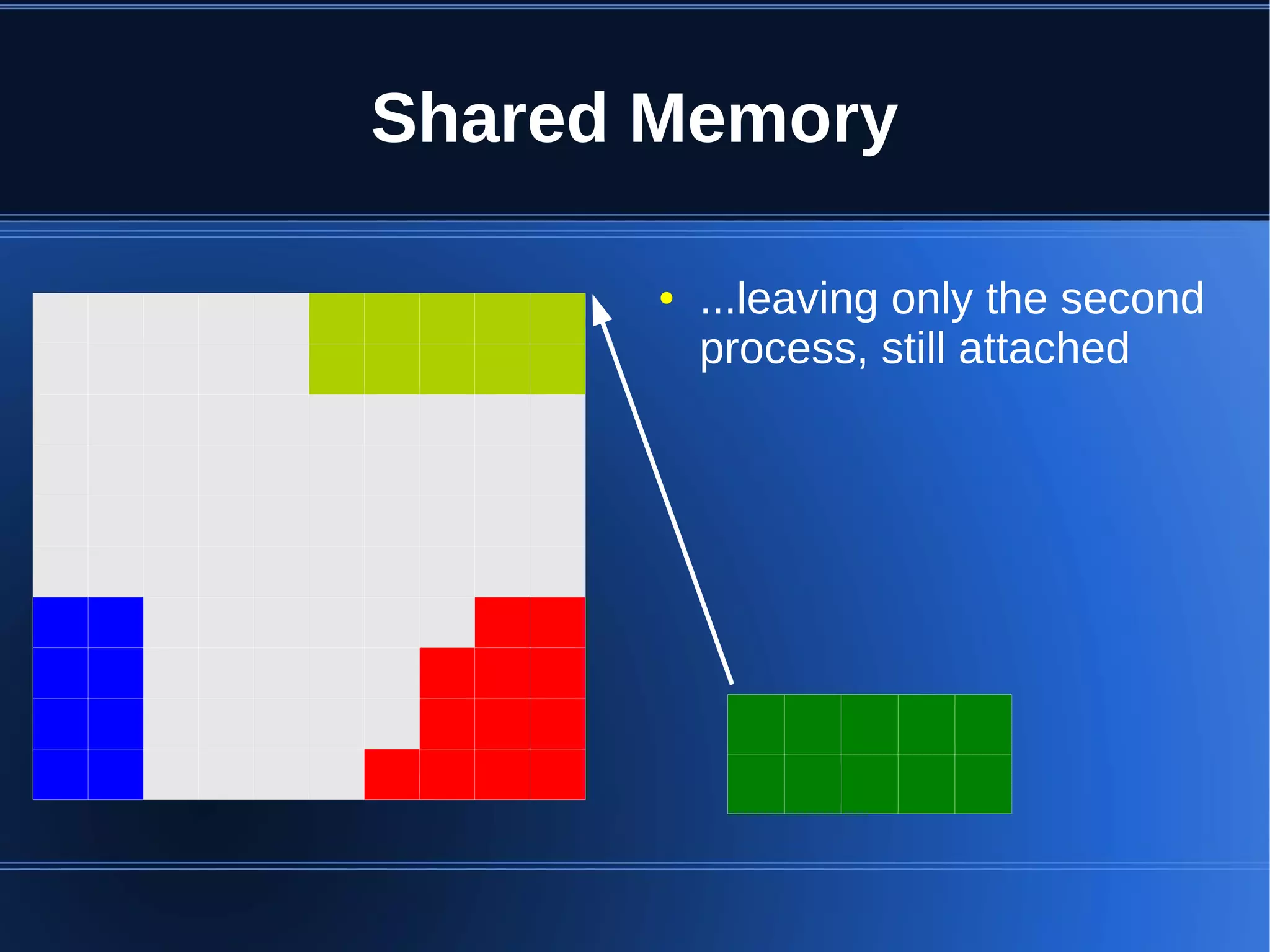

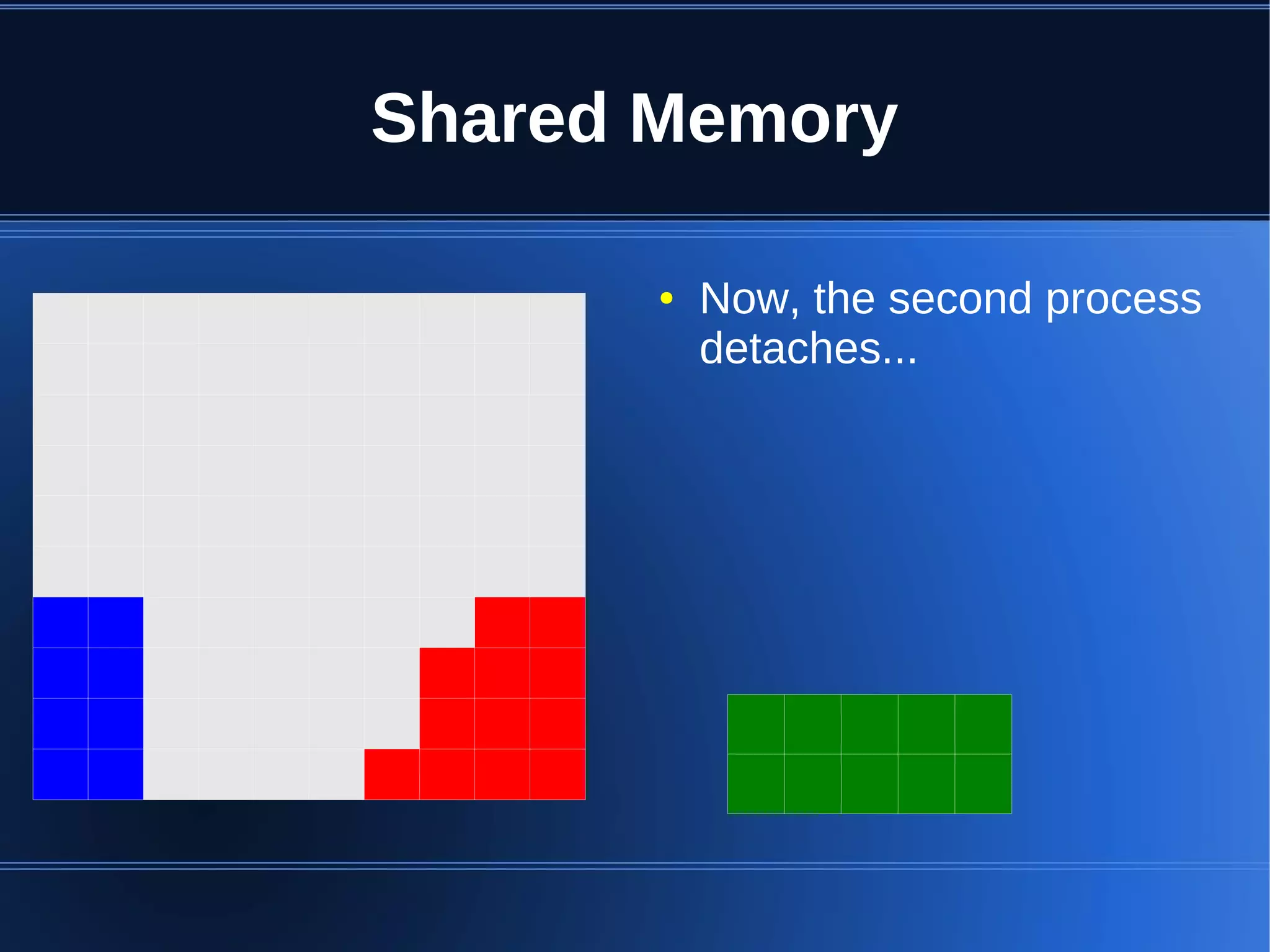

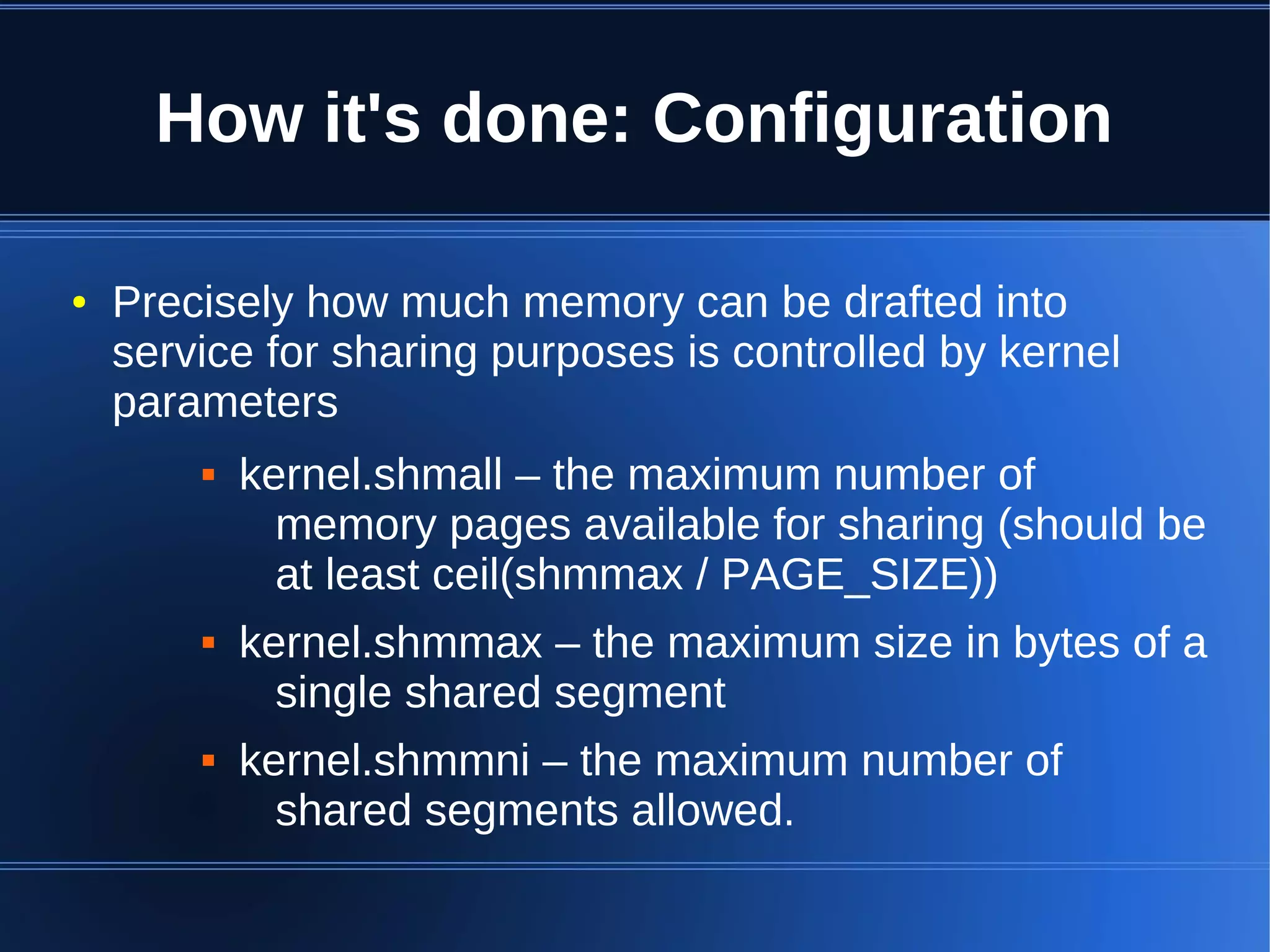

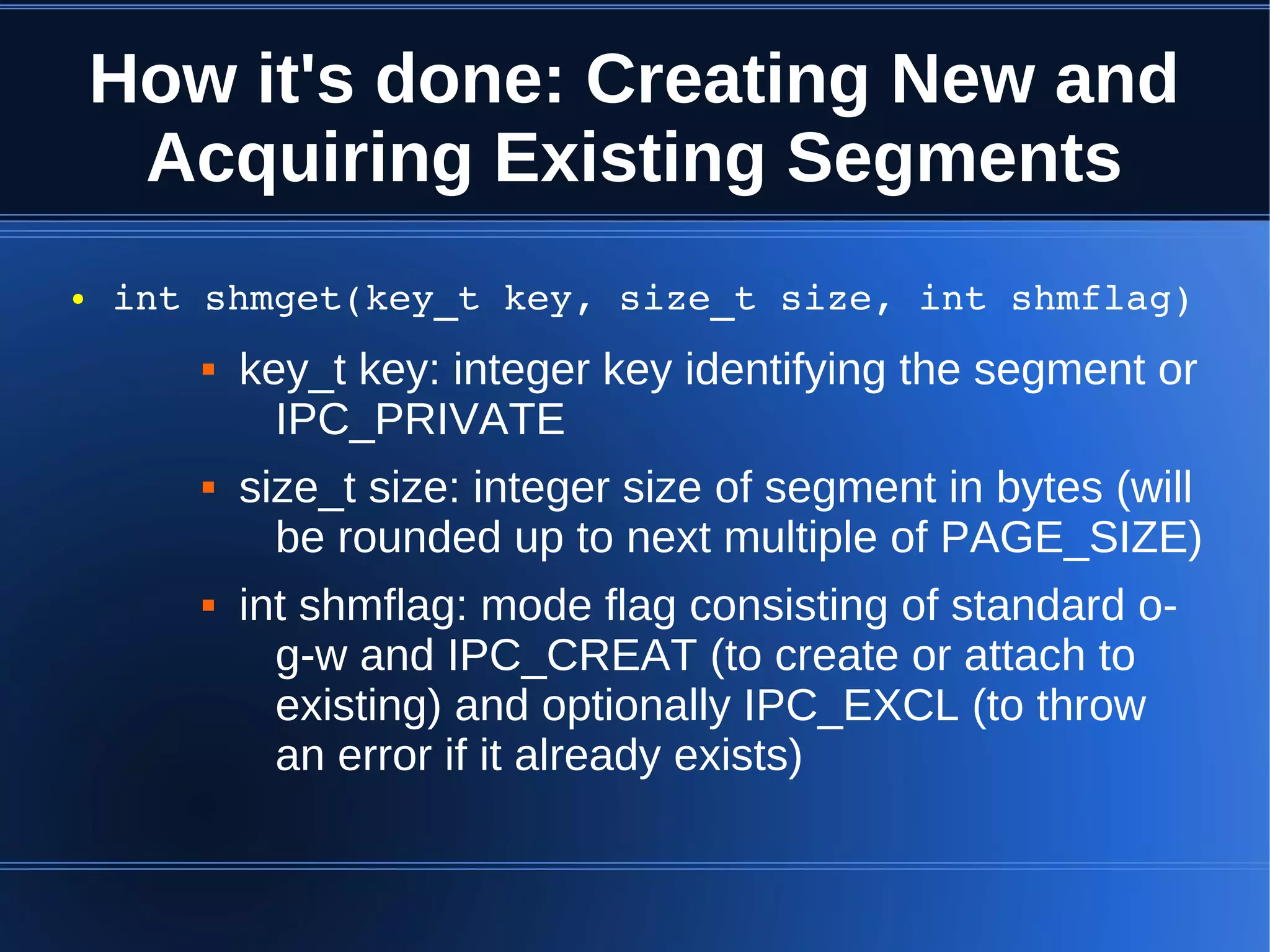

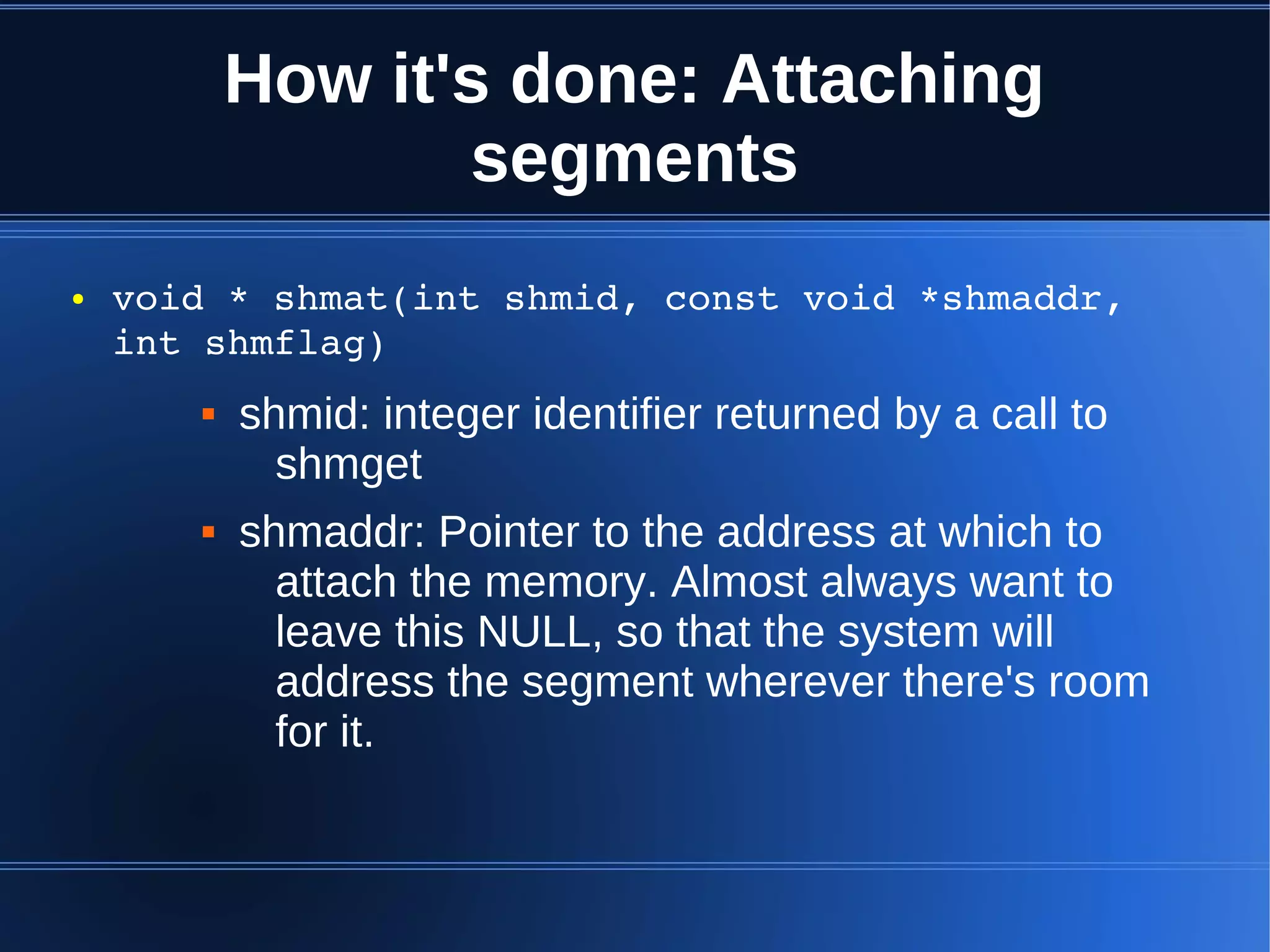

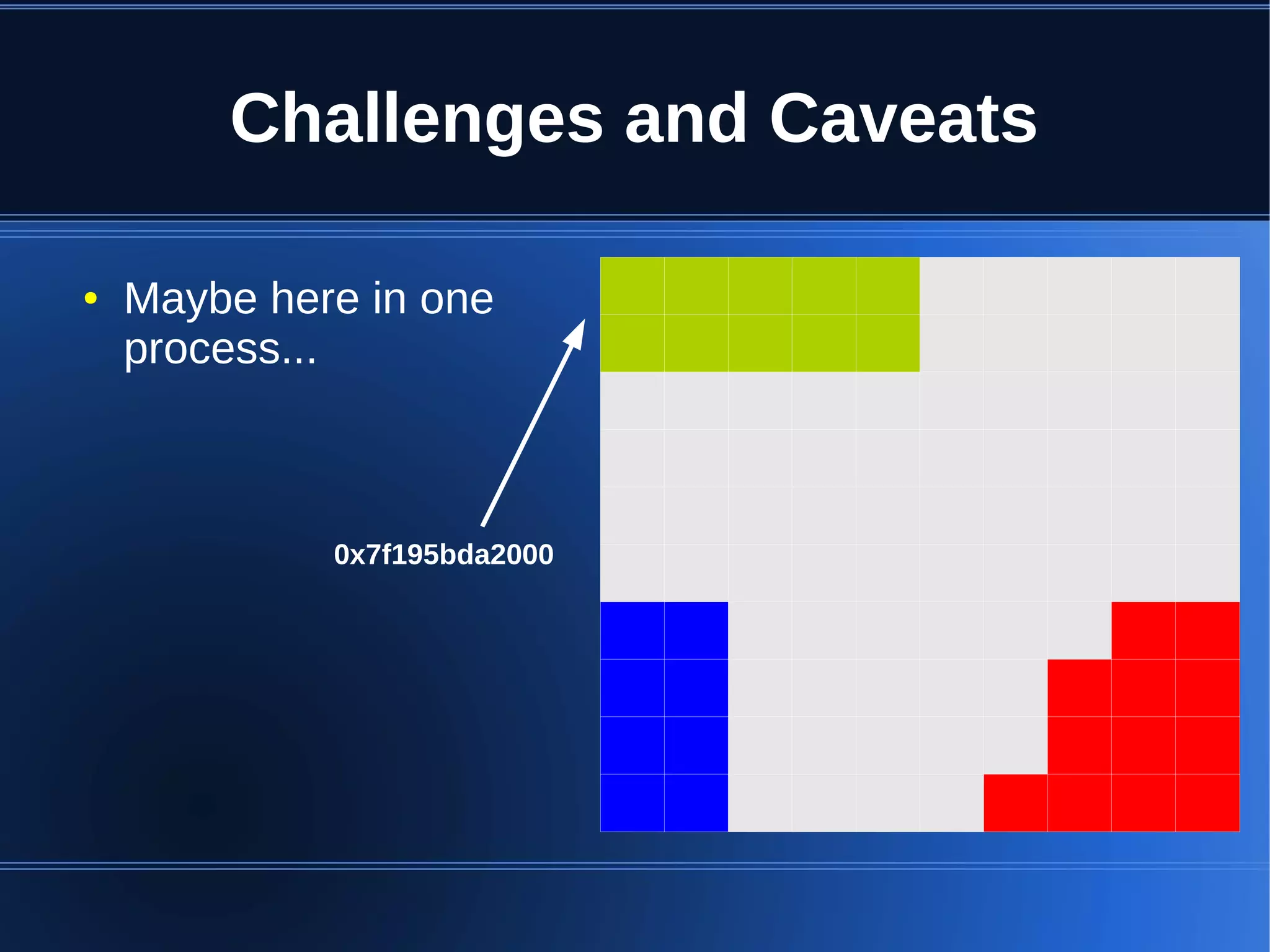

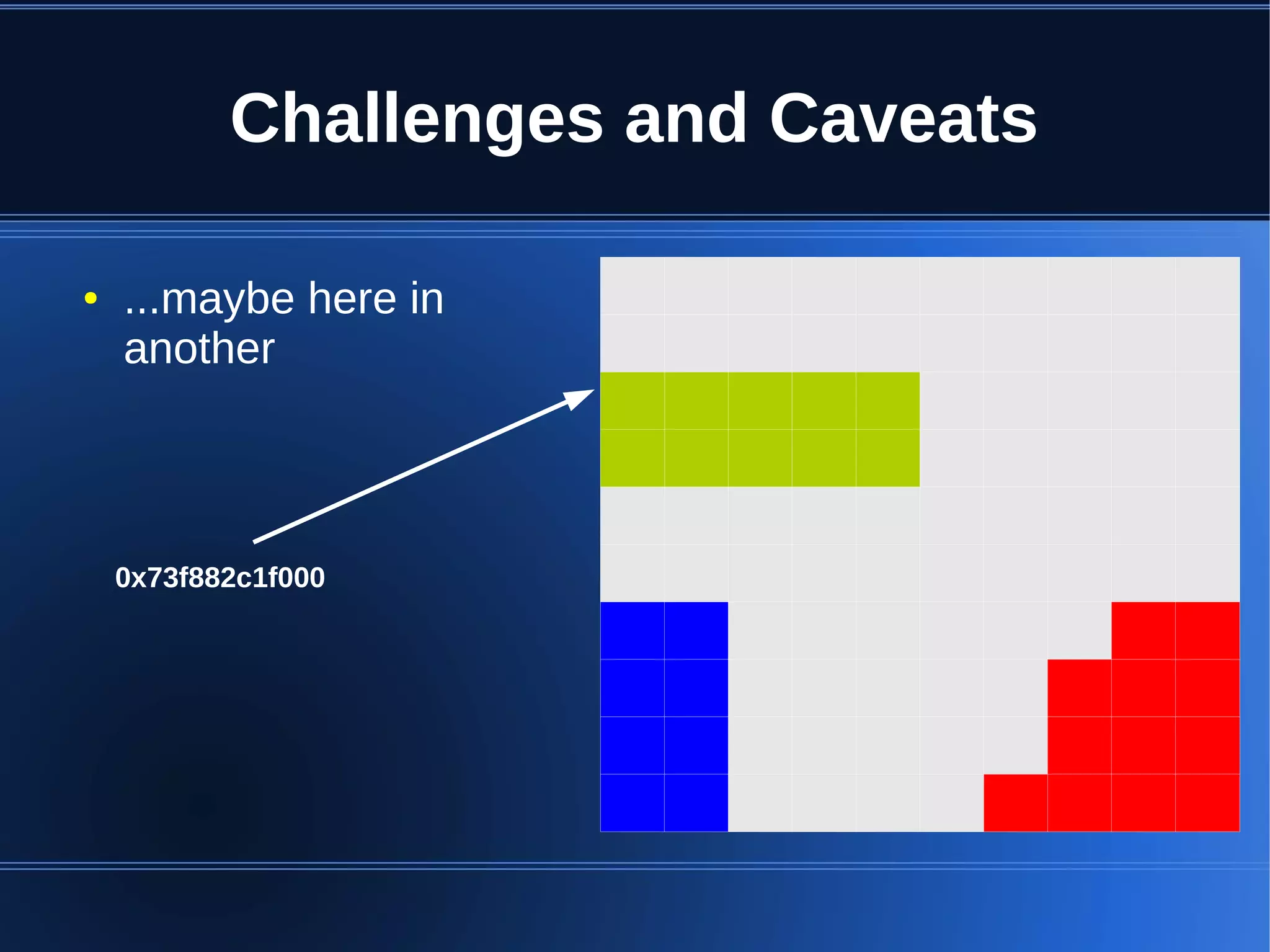

Shared memory allows processes to share blocks of memory, allowing for fast inter-process communication and data sharing. It provides benefits over alternatives like storing to disk or duplicating in memory. However, there are challenges like processes attaching segments at different addresses, requiring relative rather than absolute pointers. It also requires manually serializing data to work across processes instead of duplicating Ruby objects. Overall, shared memory can be useful for applications that need to share large read-only data or provide fast interprocess locks and messaging.