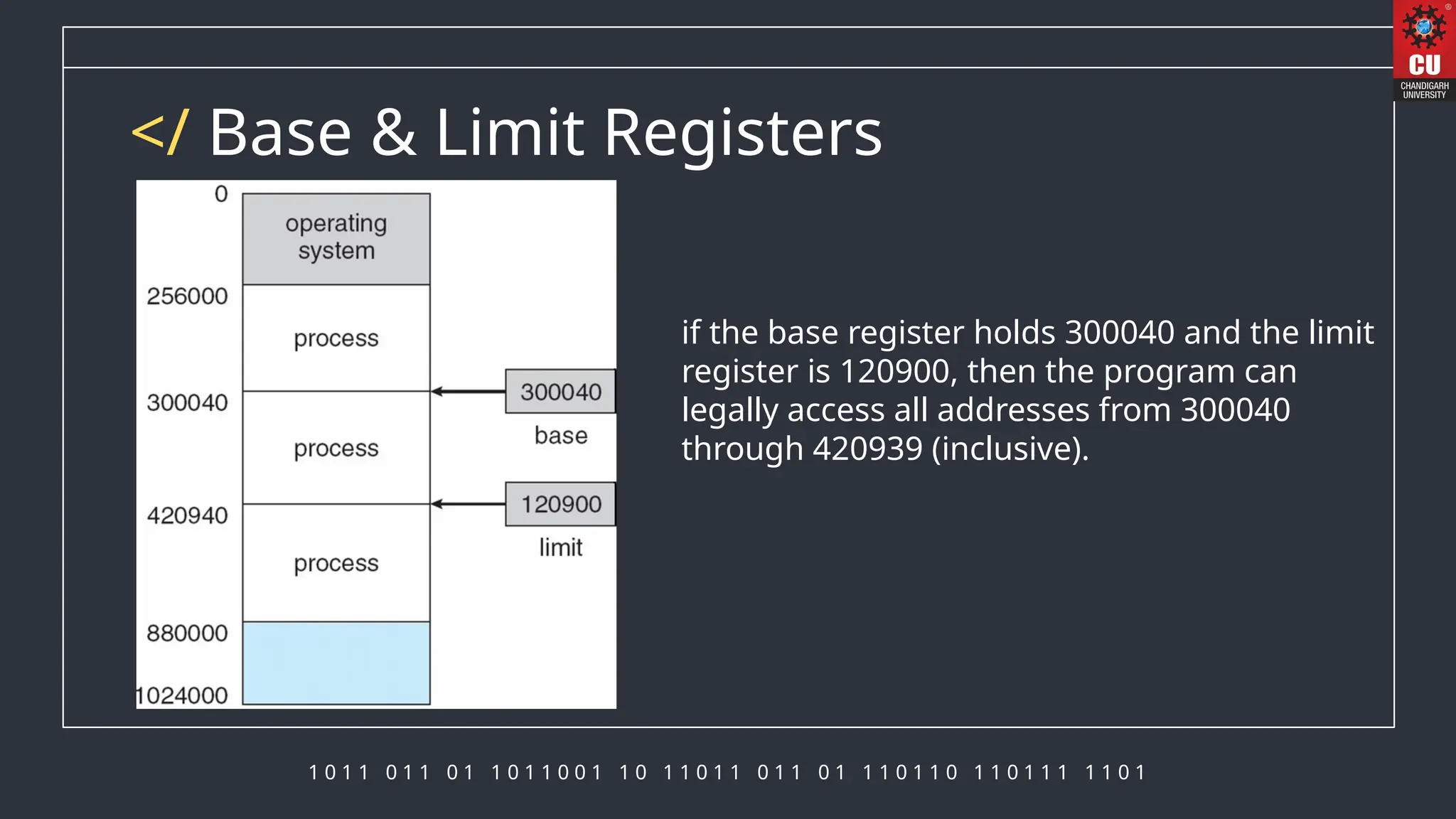

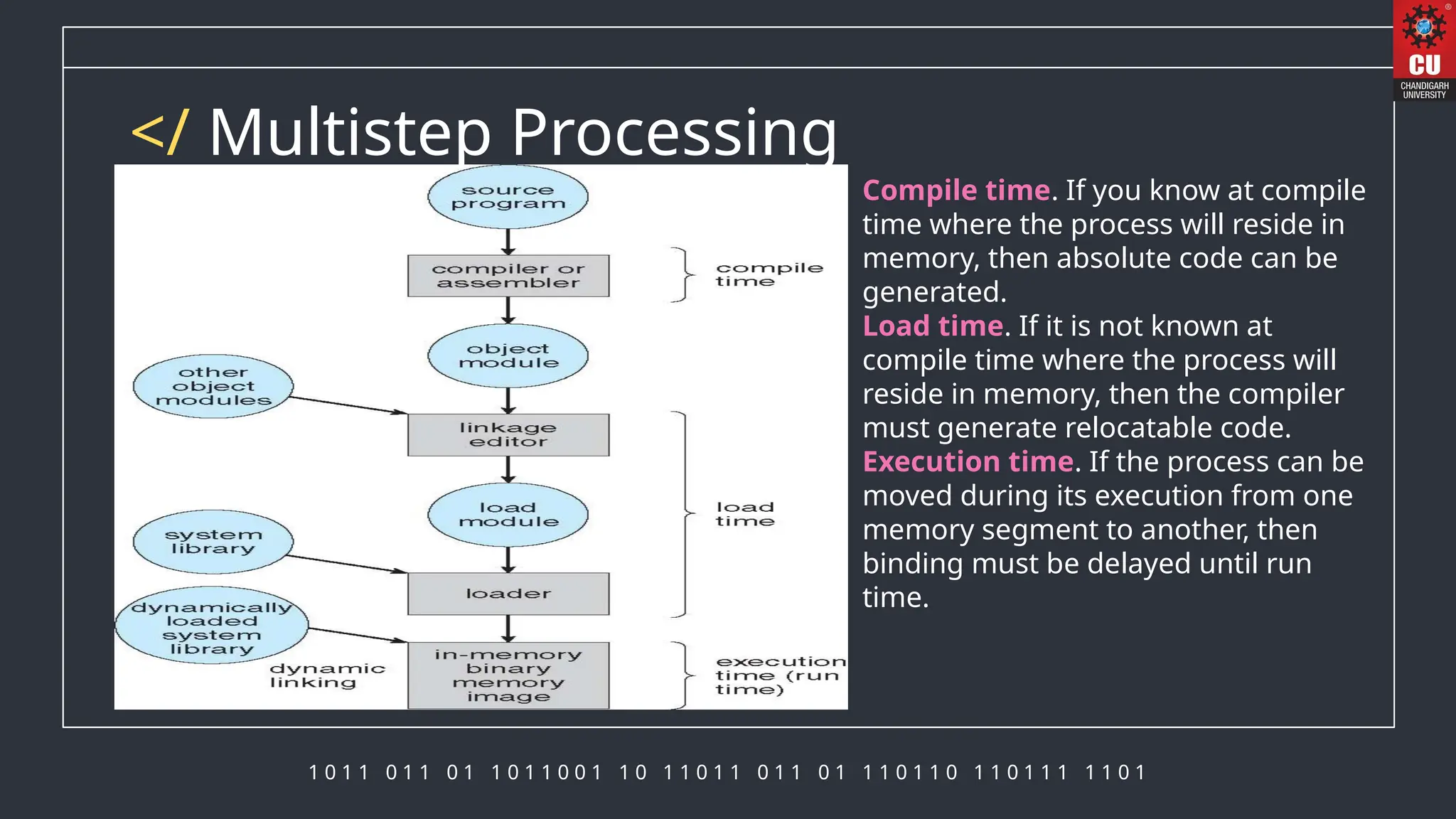

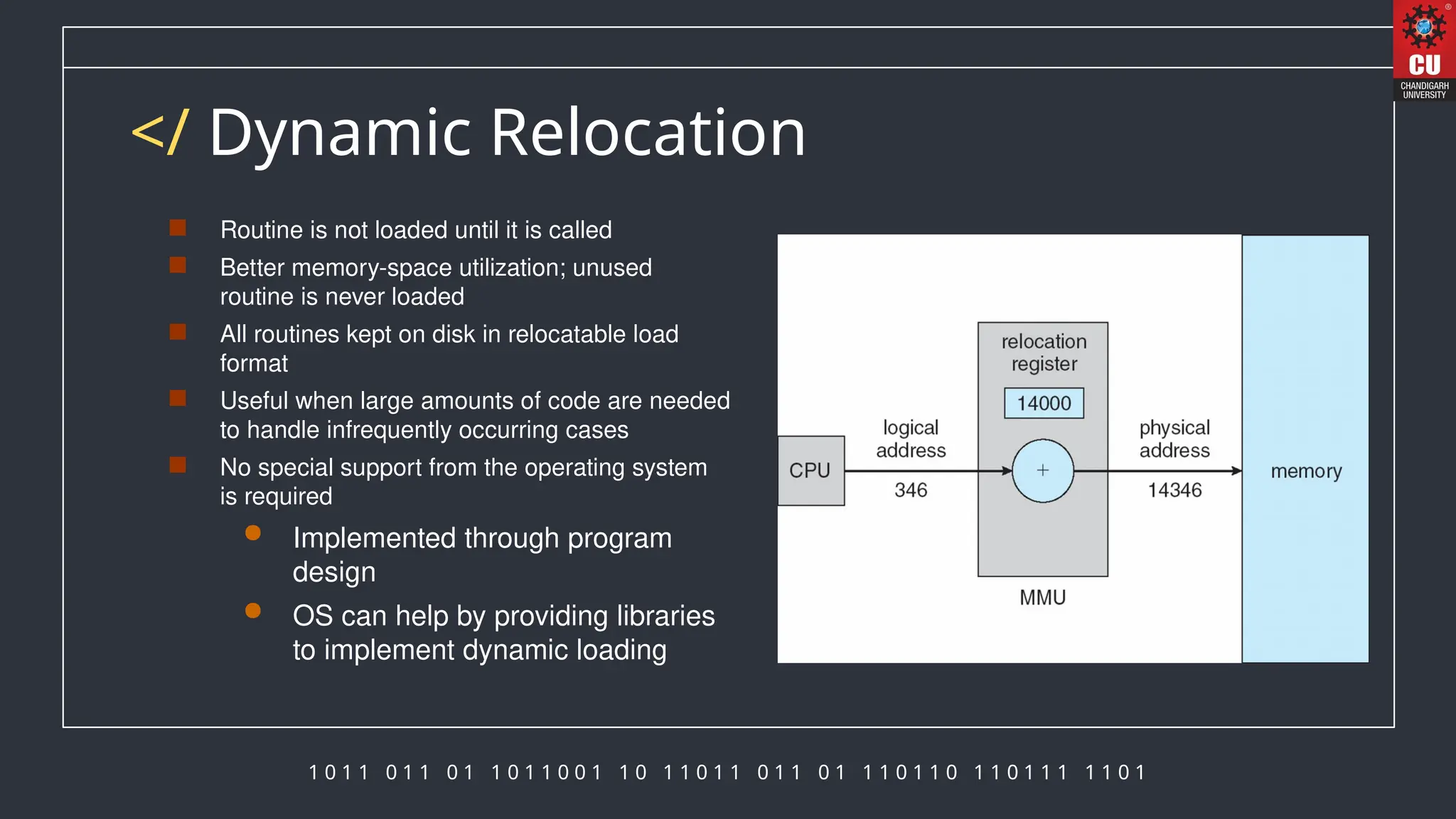

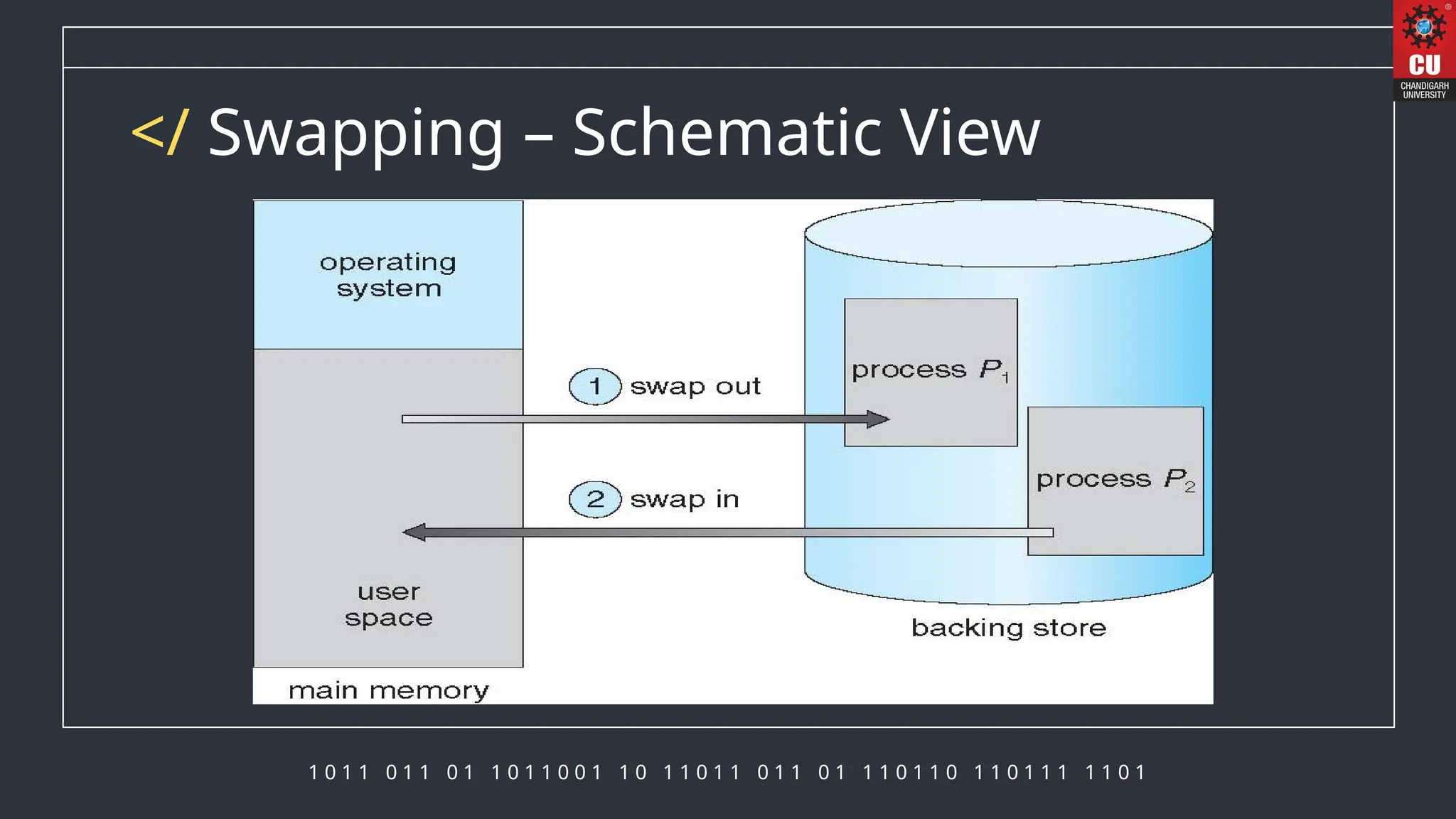

The document discusses memory management in operating systems, detailing how the CPU accesses memory, instruction execution cycles, and the roles of various registers in managing memory access. It explains address binding techniques, the concept of logical versus physical addresses, and discusses dynamic memory allocation and swapping processes to optimize memory usage. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of memory protection, particularly in multiuser systems, and provides insights into the context switch time involved in memory management.