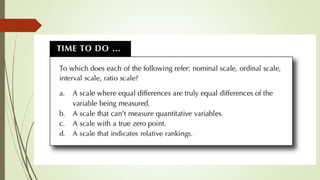

This document discusses data coding procedures for second language research. It covers preparing data for coding through transcription of oral data and using transcription conventions. It also discusses different scales of measurement used in coding data, including nominal, ordinal, and interval scales. Common types of second language data are described, such as oral data from interviews or classroom recordings. The importance of transcription and developing appropriate conventions is emphasized to facilitate coding and analysis of qualitative data.