The document discusses the role of questions in addressing tire slashing crimes, outlining reasons behind such acts, methods to identify intentional damage, and steps victims can take post-incident. It emphasizes the psychological and social factors contributing to vandalism while detailing legal implications and preventative measures. The text indicates that visualization techniques in forensic analysis can enhance understanding of complex evidence in courtrooms.

![Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law, Vol. 8(1)

73

TECHNOLOGY CORNER

VISUALISING FORENSIC DATA: EVIDENCE

(PART 1)

Damian Schofield

State University of New York

Department of Computer Science

[email protected]

+1 (410) 504 3178

Ken Fowle

Edith Cowan University

School of Computer and Security Science

[email protected]

+61 (8) 9370 6013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-8-2048.jpg)

![Visualisation represents information that has been digitally

recorded (for

example: pictures, video and sound), hand written and/or spoken

data, to show

what may have, could have, did happen or is believed to have

happened. That is

why visualising data is an important development in the

analysis and

investigation realms, as visualisation explores the accuracies,

inconsistencies

and discrepancies of the collected data and information.

This paper introduces some of the various graphical techniques

and technology

used to display digital information in a courtroom. The

advantages and

disadvantages involved in the implementation of this technology

are also

mailto:[email protected]

mailto:[email protected]

Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law, Vol. 8(1)

74](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-10-2048.jpg)

![information may

be the lifeblood of the police, a well-designed incident-based

data system

provides the infrastructure that maintains the information for

analyzing

emerging or ongoing crime problems. A primary objective of

the FBI’s

1Virginia Statistical Analysis Center, Department of Criminal

Justice Services, 805 East Broad

Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219.

2To whom correspondence should be addressed. e-mail:

[email protected]

3Departments of Surgery and Emergency Medicine, Medical

College of Virginia, Virginia

Commonwealth University, P.O. 980454, Richmond, Virginia

23298-0454.

181

0748-4518y99y0600-

Corporation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-62-2048.jpg)

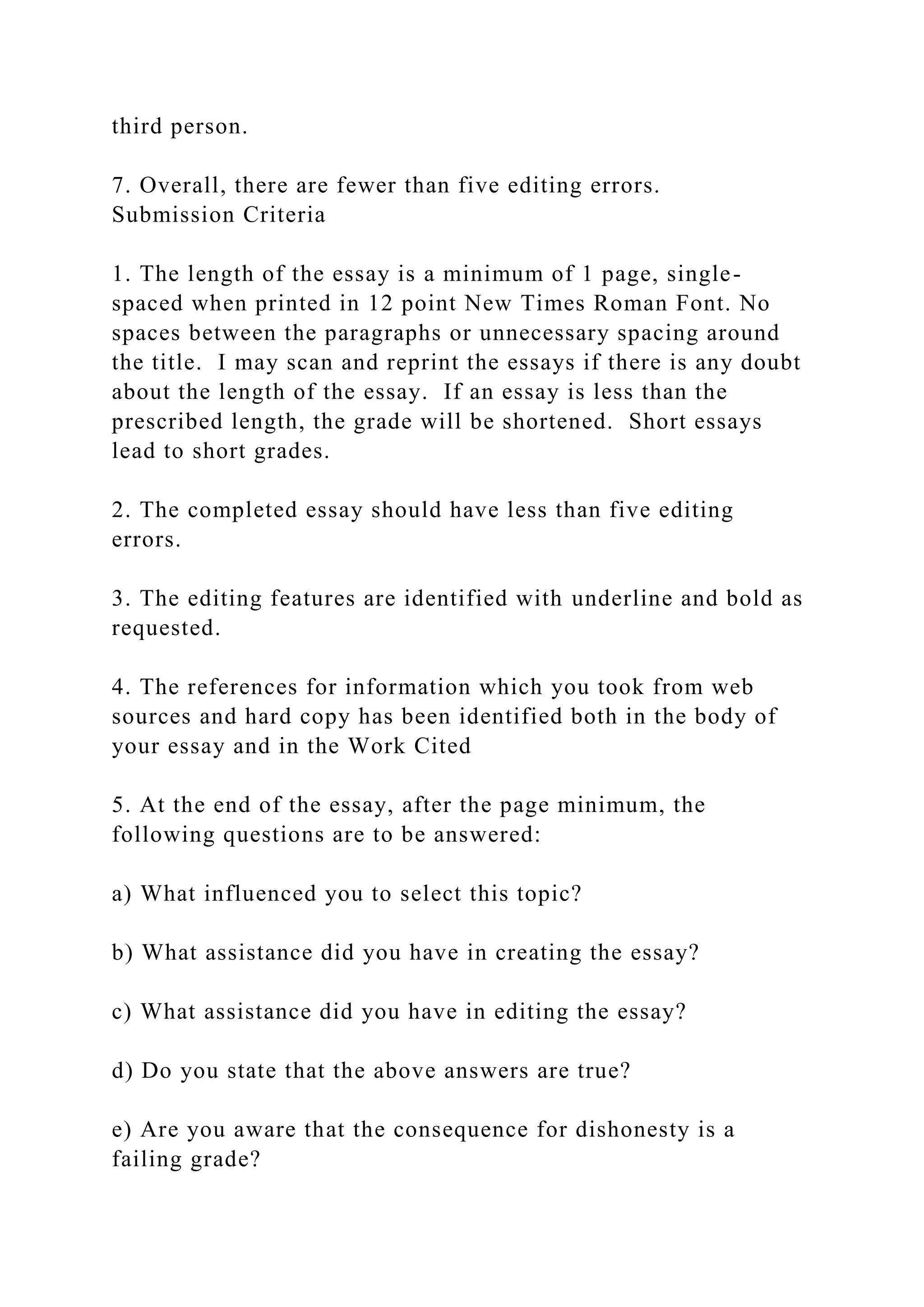

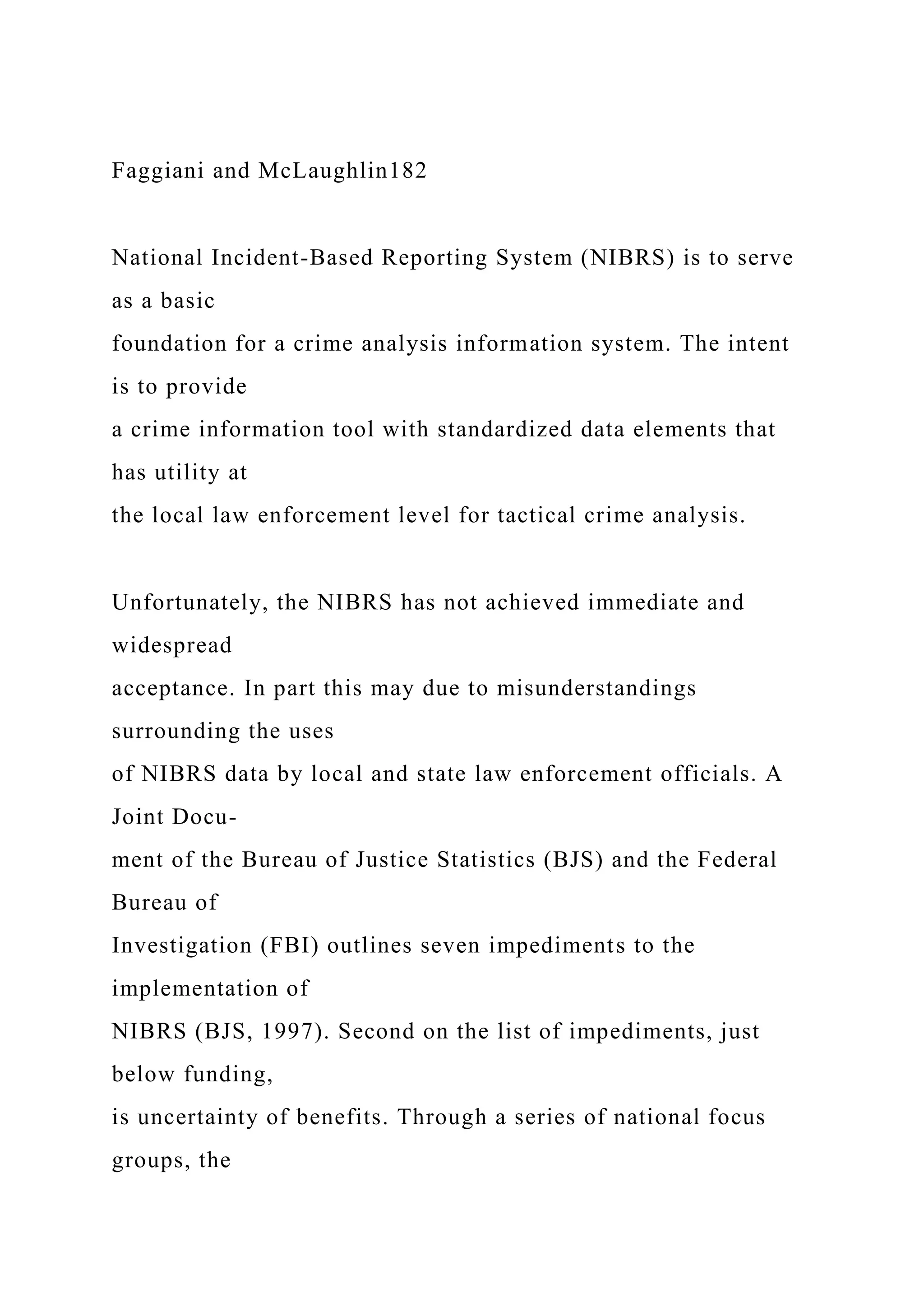

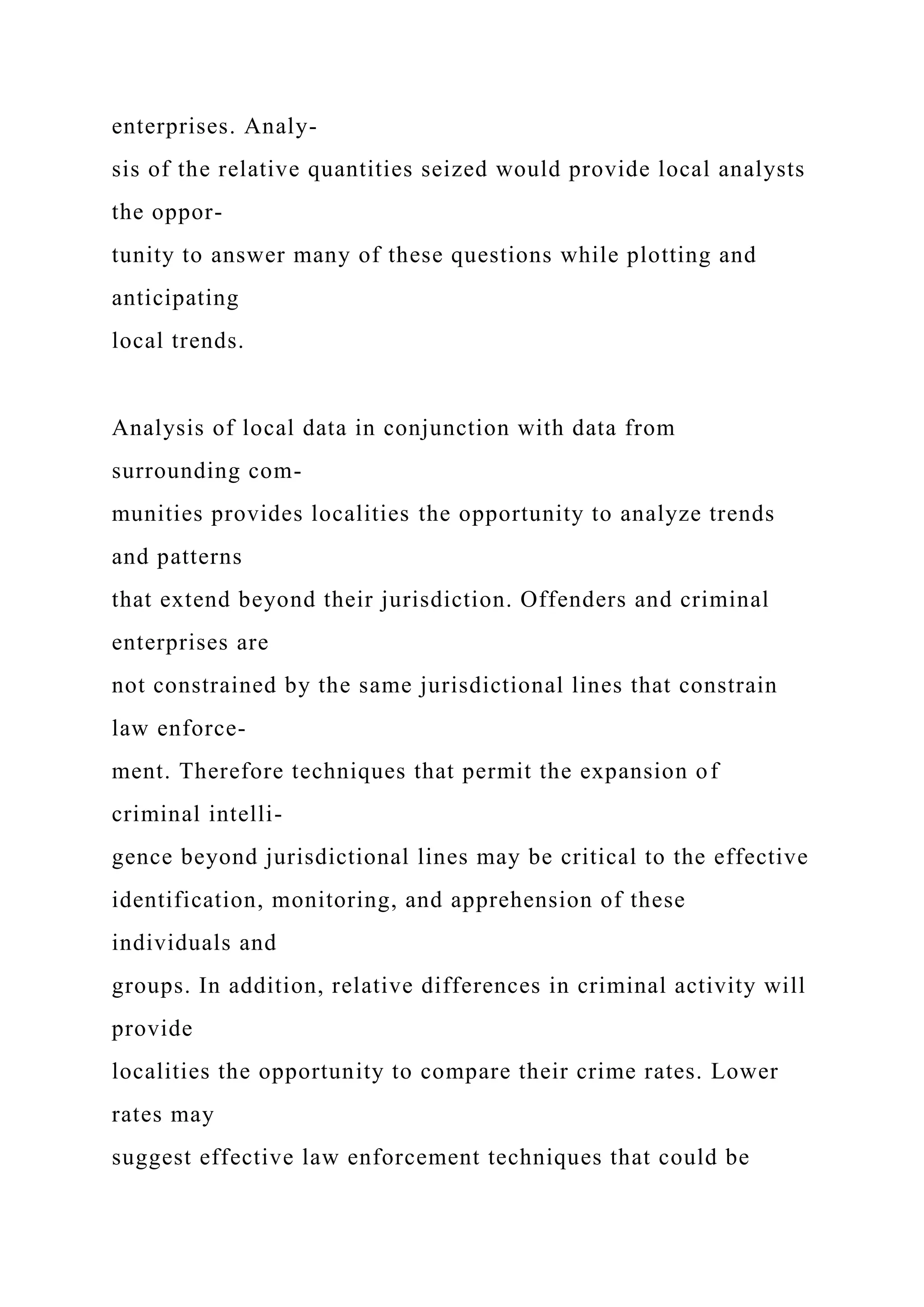

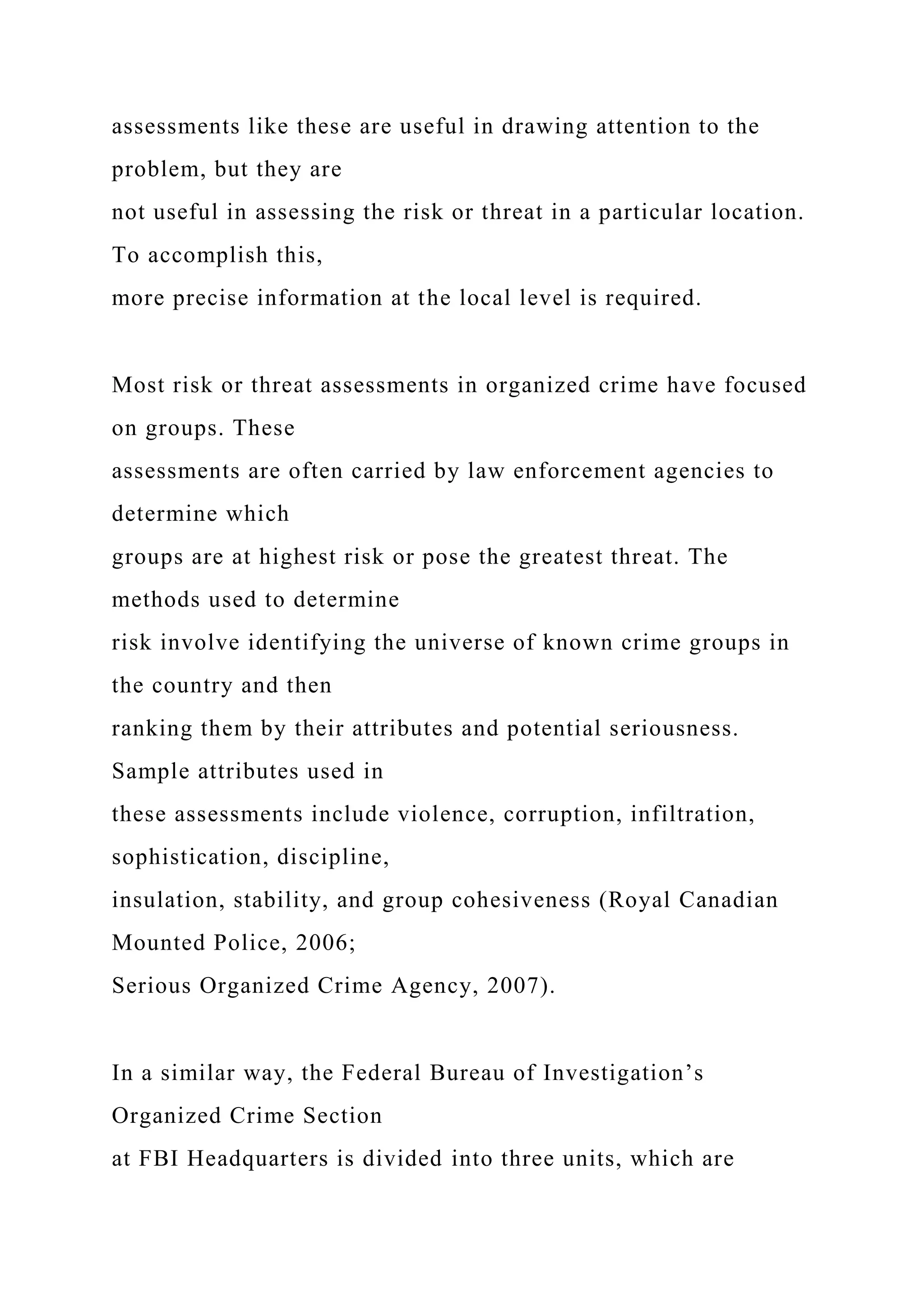

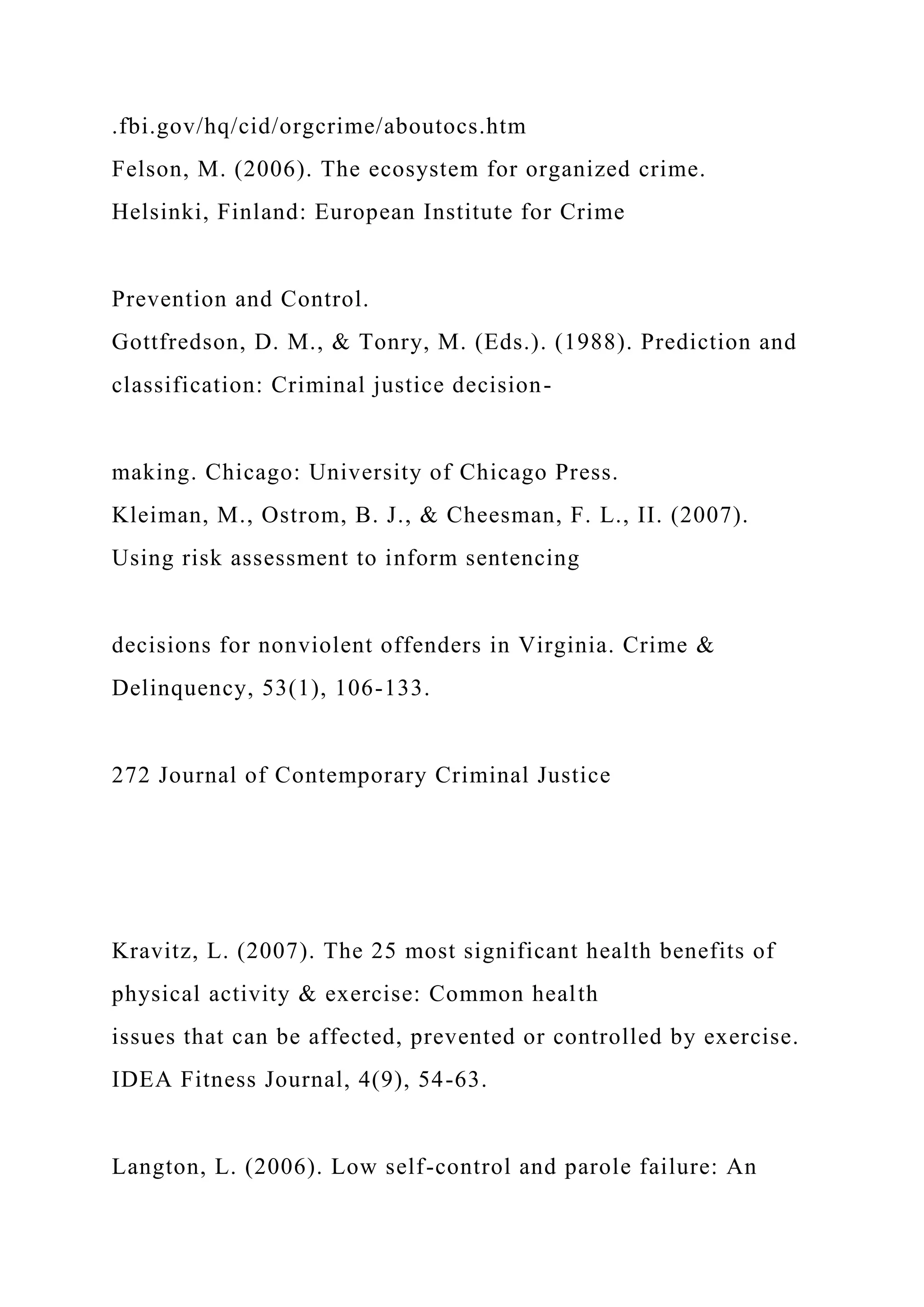

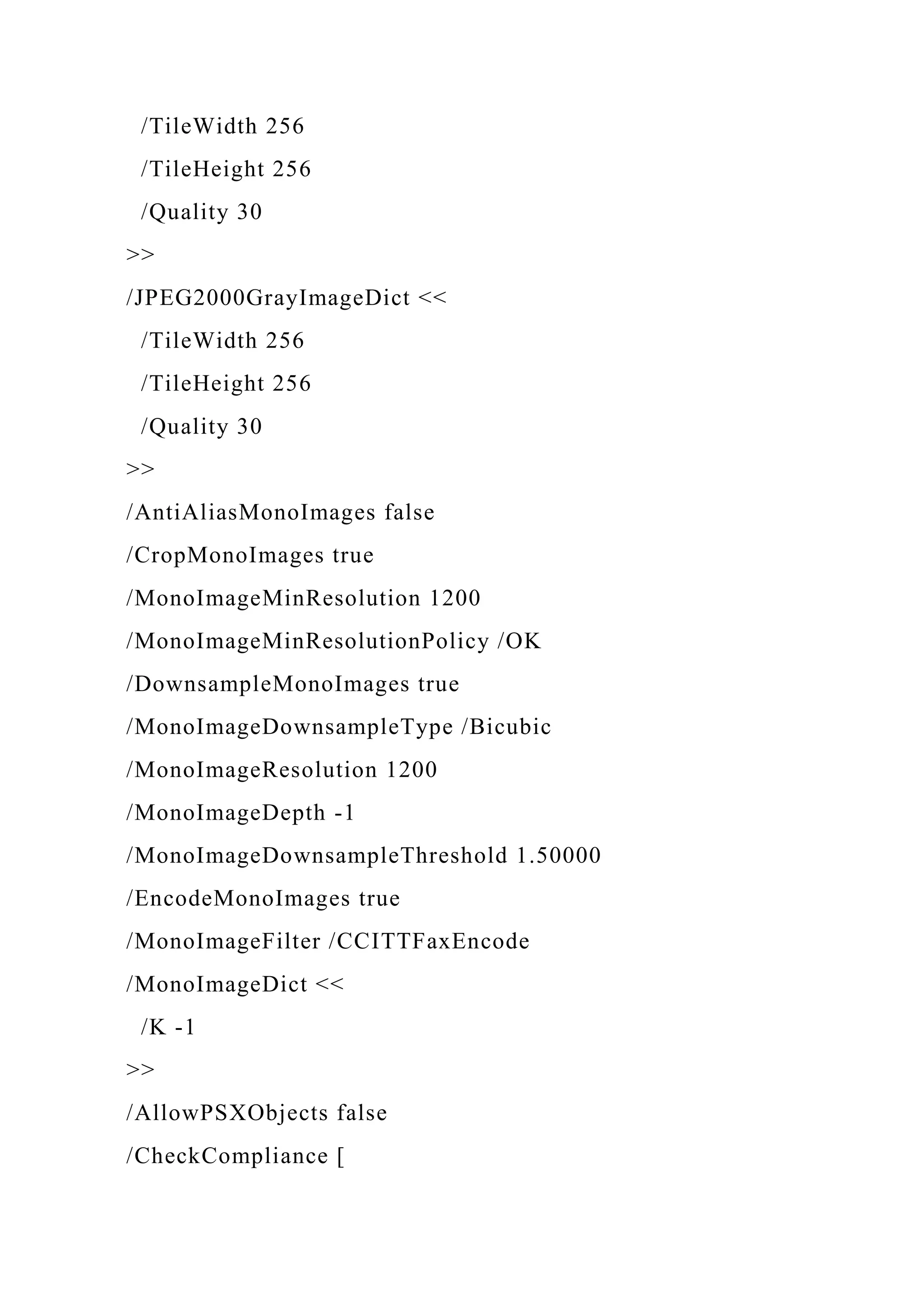

![for product

•Elastic/inelastic

nature of demand

Organized crime

as enterprise

Goal: survive

and make profit

Figure 2

A Model of Organized Crime Operation in Illicit Markets

on its way up or down?), and periodic assessments are needed to

assess the impact

of efforts and initiatives against organized crime.

Summarized in another way, Figure 2 offers a 10-factor model

for risk assessment.

The types of variables include supply indicators ([a] objective

availability of product

or service, [b] ease of movement/sale), regulation indicators](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-123-2048.jpg)

![([c] ease of entry into

market by its regulation and the skills needed, [d] law

enforcement capability and

competence, [e] level of local government corruption),

competition indicators

([f] history of organized crime in the market, [g] profitability,

[h] harm), demand indi-

cators ([i] current customer demand for product, [j] nature of

the demand—whether

elastic or inelastic). Using multiple indicators or measures for

each of the variables

(and for each product) would yield a reliable, comparative

assessment of risk.

The indicators in the risk assessment model can be combined

into an index for ease

of use in practice. The index would be based on the perceptions

and experiences of

those who might have knowledge of illicit products. Much in

the same way that the

Transparency International (2005) corruption surveys rely

heavily on perceptions of

business activities, analogous surveys at the local level could be

conducted to deter-

mine the circumstances surrounding the supply, demand,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-124-2048.jpg)

![/ZurichBT-BoldCondensedItalic

/ZurichBT-BoldExtended

/ZurichBT-BoldExtraCondensed

/ZurichBT-BoldItalic

/ZurichBT-ExtraBlack

/ZurichBT-ExtraCondensed

/ZurichBT-Italic

/ZurichBT-ItalicCondensed

/ZurichBT-Light

/ZurichBT-LightCondensed

/ZurichBT-LightCondensedItalic

/ZurichBT-LightExtraCondensed

/ZurichBT-LightItalic

/ZurichBT-Roman

/ZurichBT-RomanCondensed

/ZurichBT-RomanExtended

/ZurichBT-UltraBlackExtended

]

/NeverEmbed [ true

]

/AntiAliasColorImages false

/CropColorImages true

/ColorImageMinResolution 150

/ColorImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK

/DownsampleColorImages true](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-198-2048.jpg)

![/ColorImageDownsampleType /Bicubic

/ColorImageResolution 300

/ColorImageDepth -1

/ColorImageMinDownsampleDepth 1

/ColorImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000

/EncodeColorImages true

/ColorImageFilter /DCTEncode

/AutoFilterColorImages true

/ColorImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG

/ColorACSImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/ColorImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256

/Quality 30

>>

/JPEG2000ColorImageDict <<

/TileWidth 256

/TileHeight 256](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-199-2048.jpg)

![/Quality 30

>>

/AntiAliasGrayImages false

/CropGrayImages true

/GrayImageMinResolution 150

/GrayImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK

/DownsampleGrayImages true

/GrayImageDownsampleType /Bicubic

/GrayImageResolution 300

/GrayImageDepth -1

/GrayImageMinDownsampleDepth 2

/GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000

/EncodeGrayImages true

/GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode

/AutoFilterGrayImages true

/GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG

/GrayACSImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/GrayImageDict <<

/QFactor 0.15

/HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1]

>>

/JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict <<](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-200-2048.jpg)

![/None

]

/PDFX1aCheck false

/PDFX3Check false

/PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false

/PDFXNoTrimBoxError true

/PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

]

/PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox false

/PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

0.00000

]

/PDFXOutputIntentProfile (U.S. Web Coated 050SWOP051

v2)

/PDFXOutputConditionIdentifier ()

/PDFXOutputCondition ()

/PDFXRegistryName (http://www.color.org)

/PDFXTrapped /Unknown](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-202-2048.jpg)

![60061006c0069007400650074002e0020005000440046002d0064

006f006b0075006d0065006e00740065006e0020006b0061006e0

02000f600700070006e006100730020006d006500640020004100

630072006f0062006100740020006f00630068002000520065006

100640065007200200035002e003000200065006c006c00650072

002000730065006e006100720065002e>

/ENU (Use these settings for creating PDF files for

submission to The Sheridan Press. These settings configured for

Acrobat v6.0 08/06/03.)

>>

>> setdistillerparams

<<

/HWResolution [2400 2400]

/PageSize [612.000 792.000]

>> setpagedevice](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadtheroleofquestionsinsolvingcrimes1thero-221128144752-5369c225/75/Running-head-THE-ROLE-OF-QUESTIONS-IN-SOLVING-CRIMES-1The-Ro-docx-210-2048.jpg)