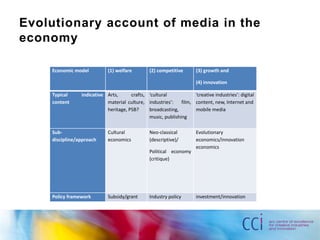

The document explores various media economic theories, highlighting the shift from dominant neoclassical paradigms to more pluralistic approaches including institutional and evolutionary economics. It addresses the challenges faced by traditional media in adapting to digital transformations and the role of public service media in this changing landscape. The authors argue for a more integrated understanding of economics in media studies to better address contemporary issues like audience agency and market disruption.

![Beyond dualistic thinking

• Economics as a discipline is more diverse and pluralistic

than it appears from the outside

• Keynesian revolution of 1930s; other challenges to

hegemony of neoclassical theory from institutionalism,

behaviouralism, network economics, post-Keynesian

economics etc.

• ‘the neoclassical approach … [is] no longer the

overwhelmingly dominant paradigm it once was’

(Wildman, 2006, p. 68)

• ‘an economic approach to the media needs to be

informed by information economics, and network

economics, institutional economics and evolutionary or

innovation economics’ (Ballon 2014, p. 76)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usydmedecspresentation24-10-14-141023183607-conversion-gate02/85/Renovating-Media-Economics-5-320.jpg)

![• ‘Economics, as a discipline, is highly relevant to

understanding how media firms and industries

operate … [because] most of the decisions taken by

those who run media organisations are, to a greater or

lesser extent, influenced by resource and financial

issues’ (Gillian Doyle, Understanding Media Economics,

2013, p. 1).

• ‘Policy researchers seem to divide roughly between …

the “market economics” and “social value” schools of

thought, and the two are often so far apart in their

assumptions and languages that they are unable to

communicate with each other’ (Entman and Wildman,

1992, p. 5).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usydmedecspresentation24-10-14-141023183607-conversion-gate02/85/Renovating-Media-Economics-8-320.jpg)

![Impasse in media economics

• Neoclassical ME vs. CPE has become a stale rehearsal

of well-worn pro/anti-market arguments

• ‘My main argument with many of the versions of the

return to Marxism today [is] they share exactly the same

worldview as the so-called neoliberals. They think there

is one solution to the problem. One thinks that the

market will solve everything, the other that doing away

with the market will’ (Nicholas Garnham, interview with

Christian Fuchs, 2014, p. 121).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usydmedecspresentation24-10-14-141023183607-conversion-gate02/85/Renovating-Media-Economics-17-320.jpg)

![Institutionalism

• Long history in the social sciences

– Middle-range theories (Merton)

– Structure/agency dialectic (Giddens)

– Historical path-dependency

• Neoclassical focus on rational choice individualism has

historically marginalised institutional economics

• Dissenting tradition: Veblen, Galbraith

• Communication studies: political economy of Harold Innis and

Canadian comms. school

• ‘it is … on individuals that the system of institutions imposes

those conventional standards, ideals, and canons of conduct

that make up the community’s system of life’ (Veblen 1909

[1961], p. 38).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usydmedecspresentation24-10-14-141023183607-conversion-gate02/85/Renovating-Media-Economics-18-320.jpg)